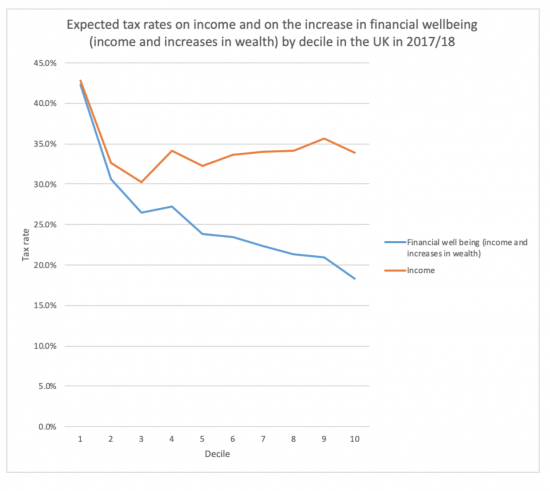

In a paper published this week, I showed that the effective tax rates on those enjoying increases in their financial well being from income and increases in the value of their personal net financial wealth are unequal across the UK population. When the income and increases in asset worth of each decile group of taxpayers in the UK are combined and the total taxes paid on income and wealth are considered then for 2017/18 this chart of effective tax rates by decile results. A decile is simply the people in each successive 10% group of the UK taxpaying population, numbered from bottom to top:

In a paper published this week, I showed that the effective tax rates on those enjoying increases in their financial well being from income and increases in the value of their personal net financial wealth are unequal across the UK population. When the income and increases in asset worth of each decile group of taxpayers in the UK are combined and the total taxes paid on income and wealth are considered then for 2017/18 this chart of effective tax rates by decile results. A decile is simply the people in each successive 10% group of the UK taxpaying population, numbered from bottom to top:

Those with most wealth pay vastly less in overall tax on the improvement in their financial wellbeing than do those who pay have least income and wealth. This is not a value judgement. It is a fact. In that case it is also a fact that they have the greatest capacity to pay more tax at present.

The question that does then arise is in what way that increase in tax should be raised if it proves to be necessary to increase the overall UK tax yield if at some time that is considered necessary? That might be because macroeconomically that is thought to be the case. It could also be because it is considered desirable in itself to reduce the financial inequality in the UK that our current tax system contributes to, which should not be its purpose or outcome.

This is an important question for a number of reasons. First of all there is the simple question of timeliness: simple reforms to existing taxes are fairly easy to introduce, and so can be delivered quite quickly. New taxes do, in an era when consultation is considered necessary, take a long time to create and implement.

Then there is the question of acceptability. So far it is not apparent that the UK has generally accepted the idea of a wealth tax as such: the chance of a tax of this nature surviving in the long term is not clear. That makes it an uncertain route to propose.

Likewise, we have no infrastructure for a land value tax (LVT) as yet. That does not mean we could not, of course: it just means it is not a solution that is available now.

Nor, come to that, do we have the infrastructure for a financial transaction tax in place, and the yields from such a tax are in any case open to doubt. We may want such a tax to stop excess trading but whether that is the right route to go is, in any event, not proven when we now know that short selling can, for example, simply be stopped by regulation.

In addition, replacing inheritance tax would take time. It is highly likely to be desirable, but it is not an overnight solution.

All these issues matter. The demand for tax increases to supposedly 'pay' for the coronavirus crisis and the increased spending that will follow (or rather, to neuter the impact of that spend so that inflation does not arise) will be significant soon after the crisis ends. So, whilst long term issues need to be on the agenda, if tax is to be reformed now in ways that are likely to be just and equitable then that requires that any reforms have to be delivered within the existing tax framework. That rules out anything other than reviews on these long term issues for the time being.

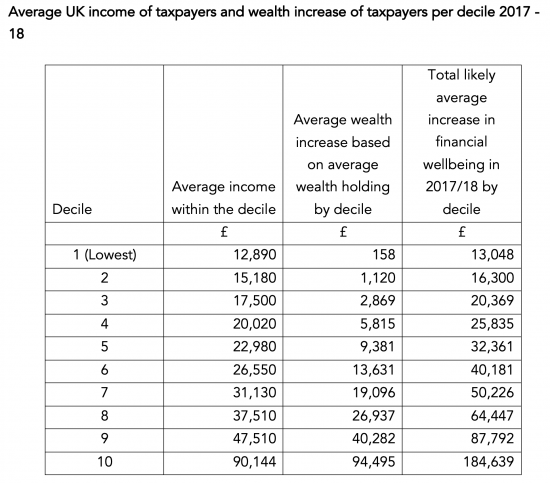

The Tax After Coronavirus (TACs) series will as a result focus on those changes to existing tax rules that might refocus the tax system so that more tax is paid by those best able to make that payment. It is apparent that this is not those in the lower deciles of taxpayers. This is indicated by this table:

What this shows is that income and wealth gains are very unequally spread in society. In that case the tax changes that will impact in the shorter term on those in the higher deciles of taxpayers will be focussed upon most heavily. In addition, those changes that might assist those on the lower levels of both earnings and wealth by reducing their tax rate will also be highlighted. After all, redistribution requires that the interests of all taxpayers be taken into account, and the tax liabilities of those on lower earings need to be reduced wherever possible as a consequence.

Those changes will broadly be of three types. First, there will be an emphasis on equalising tax rates on equivalent sources of income or allowances. This has several advantages. It creates level playing fields. By itself that is a definition of equity. That also makes it very hard to object to. And it removes considerable scope for tax abuse: a great deal of tax avoidance activity is about seeking to lower rates of tax simply because that option is available in the tax system, and not about cancelling tax altogether.

Second, it is about those things that should be taxed that are not, but should be.

And it is about creating a more progressive tax system by changing tax rates without challenging, as far as possible, the first objective.

There is considerable scope for reform in all these areas. A lot of blogs will follow on this theme. That is because it is vital that all politicians, from whatever party, know the options that are available to them when considering this issue. The aim of the Tax After Coronavirus project is to make clear that these options exist, as well as to provide the reason why they should be used if a fairer and more equitable tax system that delivers great social justice, removes inequality and improves the well being of those on the lowest incomes in this country is to be created. That is why this focus has been chosen.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here: