The reasons why wealth needs to be subject to additional taxation has been discussed in another Tax After Coronavirus (TACs) post, with all links being supplied there and so it will not be repeated here.

What was also discussed in that post was that the necessary short term changes to wealth taxation fall into three groups. They are, firstly, to equalise tax rates on equivalent sources of income or allowances. Second, it is by reconsidering those things that should be taxed that are not but might be if the goal of greater equality is to be achieved, and vice versa. In other words, those parts of available tax bases subject to exemptions and reliefs need to be reviewed. Third, it is about creating a more progressive tax system by changing tax rates without challenging, as far as possible, the first objective.

Reforming council tax

Council tax is the main tax charged by local authorities in the UK. This commentary relates only to that part of the tax paid by households and does not concern the charge to business.

The comments made here relate only to England and Wales: different arrangements apply in Scotland and Northern Ireland and those in Wales do differ in some ways from those in England.

Council tax was introduced in haste in 1992 in Scotland and 1993 in England and Wales. It replaced the deeply unpopular community charge, or poll tax, which had, in turn, replaced local rates in England and Wales in 1990. Unlike the rates system, which was supposedly based on the rental value of a property the council tax is, again supposedly, based on the property's market value, albeit that which it had in 1992 (even if it had not been built then).

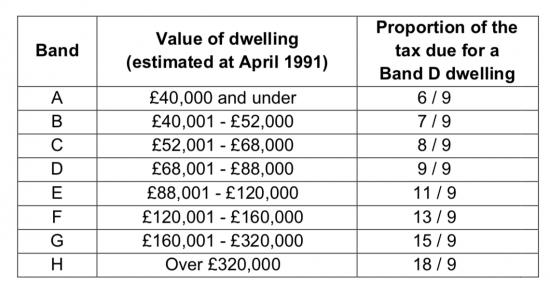

In England every property is allocated to one of eight tax bands (A to H): there are nine bands in Wales (A to I). This allocation is based on the deemed value of the property in 1992. The higher the value of the property, the higher is the tax band to which it is allocated, although all properties valued above £320,000 are in band H (or I in Wales).

By law band A tax owing has to be one-third of the tax due on Band H in England.

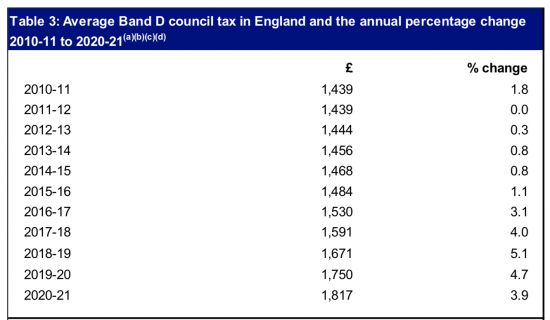

The average Band D council tax in England - which is the average sum due - has changed as follows over the last decade:

Increases in recent years have considerably exceeded inflation rates.

The taxes due in each valuation band are always related to those due on Band D, according to the following formula:

This is where the issue becomes very significant for the purposes of wealth taxation. What is readily apparent to even the most casual observer is that to run a taxation system based on 1992 property values makes no sense: the opportunities for the wrong tax rates being paid is enormous. This tax is by no means as efficient as many claim as a result.

Second, it is readily apparent that income and wealth inequality in the UK does not work on the ratio of those with the highest income or wealth having no more than three times that which those with the lowest income or wealth have. Median wages in the UK are around £30,420. But, over 900,000 people in the UK have taxable income of more than £100,000 a year.

It is apparent that there is a massive disparity in earnings in this country. In the case of wealth the disparities are even greater.

In that case council tax is deeply regressive simply because insufficient progressiveness is designed into it.

Potential reform

There are three very obvious immediate reforms that are possible to council tax.

First, there could be a revaluation. Online data now permits this with ease and low cost, subject to appropriate appeals procedures.

Second, the idea of eight or nine bands has to be abandoned. There is no reason why another eight or more could not be added at the top end, increasing the sums due on high-value properties quite considerably, and providing a better basis for the taxation of wealth (with those in retirement being allowed to roll up liabilities until death).

Third, more bands and exemptions are required at lower level: it is wrong that households likely to have very low income should pay two-thirds of the sum due on an average house when they are unlikely to have the capacity to pay that sum, whilst those with low incomes and who are on essential benefits should be exempted from this tax, which is not universally the case at present.

In the longer term the tax needs replacement: it is almost certainly the case that a land value tax is fairer and more efficient. But in the shorter-term the reforms noted could address a great deal of the inequality that this case creates.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

Good stuff. There have been a lot of proposals for extra bands in the manner you suggest – most recently from the IFS, also from the Lyons Review back in 2007.

Do you have a view on whether a banding system or a simple percentage charge – e.g. 0.5% of the assigned value – would be preferable?

Just a note on the rolling up of liabilities – council tax is payable by the occupant not the owner, so conceptually this might need changing (although I accept that very few will be renting Band H properties).

I think you are right to call for additional bands at the bottom end as well as the top – this is something that is often missed. I would also draw attention to local authorities’ attempts to sweat as much income from council tax as possible e.g. by playing fast and loose around student exemptions, probate exemptions, ratcheting up empty property council tax even when owners can’t offload or rent their houses.

I would use bands for ease, but man open to persuasion

The “ease”-est method is not using bands, but the straightforward percentage of property value.

The property value can be taken straight from the Land Registry, which is updated whenever a property changes hands. I think it’s an acceptable “lag” that different properties changed hands different times in the past. All taxation systems have flaws as you try to approach 100% accuracy. You could have a system where an occupant could have their assessed value updated without having to move house.

There appears to be a major contradiction in there – and a penalty on those who move that is not fair

You airily dismiss the task of revaluation as something that can be done “with ease and low cost”. It needs to be done – it beggars belief that this tax is based on (often hypothetical) values three decades ago – but politicians have be reluctant to grasp that particular nettle for many years. Many losers, few winners.

On rolling up liabilities until death, for perhaps two or three decades, how will local authorities be funded while (to put it bluntly) they wait for retired people to die? Perhaps we should be gently encouraging retired people to leave their large family houses (which, if they cannot afford the council tax, they probably cannot afford to maintain either) and trade down to something more appropriate to their needs and means? Capital rich, cash poor? For Pete’s sake, spend the kid’s inheritance! You only live once. Or give them some cash so they can buy their own place now.

Have you noticed the mass of data on line to ease revaluation?

And roll up is just a deferred payment

It could back a bond – or the government could lend against it

Not an issue at all

We can and should skip an interim remedy and move straight to a land value tax.

Every owner of an interest in land must complete a return each year. This will show:

1. The current value of the interest in land, self assessed by the taxpayer

multiplied by

2. A figure (1, 2, 3, 4, 5 or 6) based on the property’s greenhouse gas footprint

multiplied by

3. A rate set by the local authority with the money going to that authority and a rate set by national government with the money being redistributed back to local authorities in such a way as the even out regional inequalities.

In order to prevent late or non- compliance, a 10% penalty will be imposed if a return is filed and/or the tax is paid after the due date. If, after six months, a return has still not been filed or the tax has still not been paid, the local authority may confiscate the interest in land, liquidate it, settle all taxes that are due and return what’s left to the original owner.

In order the keep the self-assessment of value honest, the local authority will have the right to buy the interest in land for 105% of the value shown on the tax return.

In order to enable taxpayers to have a survey done to determine the property’s greenhouse gas footprint or, better still, carry out remedial work to improve it, taxpayers will be allowed to put their property in band 4 for the first 5 years.

The Tax After Coronavirus (TACs) project is about the fixes that can be made now when the economy is already in shock

We simply do not have the capacity to move to LVT in such a situation

And there are higher priorities

Using bands doesn’t mean you have to have a top band: after band Z, have band AA, then AB etc

You can approximate an LVT by just having a proportion of the value, representing the rebuild cost of a modest dwelling in a marginal location be untaxed (or taxed at a much lower rate if it’s necessary to have some tax on the cheapest dwellings for electoral reasons). This might be more acceptable politically than LVT, even if worse theoretically, because big houses, even in low value locations, would pay some tax.

I think it can so closely approximate LVT the change may np be required…or it can be transitioned over time

I really like your thinking on this Richard. I’ve always believed council tax is terribly regressive and hugely punishing to those on lower incomes.

What you mention about data on property values is not only true, but there are several APIs for websites like Zoopla or Rightmove that would allow you to do a paper exercise from actual sales values very easily. So the taxation burden could be (fairly accurately) demonstrated on paper without having to get any data from local authorities.

Can you scrape that data?

I was told it was hard…..

The actual sales values are open data, so no scraping required (though some database skills might be needed):

https://landregistry.data.gov.uk/

The Zoopla API has various calls to get more specific data, like average prices in an area. They have something they call the zed index, about indexes of price data in each area, which might be a good proxy for values. I couldn’t see how you could get all values from the API though.

https://developer.zoopla.co.uk/docs

The landregistry have their own price index you can search here: https://landregistry.data.gov.uk/app/ukhpi

Either way, it’s doable with a little work. Do you think you would need all house sales in each area for a good model?

I’d love to see the answers

The Crown owns the Land Registry data, of course. About 1 million properties are sold each year, but there are about 25 million households, so the data for current valuations is pretty sparse.

Zoopla (like some other similar private businesses) has proprietary algorithms to generate its own “valuations” for each property in its database. I understand there is some debate among professional property valuers about how accurate (or not) its valuations are. Their API won’t let you “scrape” (i.e. steal) their entire database but perhaps they and their private equity owners would be willing to license it, for a fee.

Council tax raises about £33 billion a year (about 5% of the total) and accounts for about half of local authority funding. I’m not convinced it makes a great deal of sense to outsource the measurement of the tax base to a private business. (Silver Lake bought Zoopla for about £2 billion a couple of years ago, which gives you an idea of what they think it is worth: perhaps it should be nationalised.)

Don’t get me wrong, I wasn’t suggesting using Zoopla data for an actual valuation mechanism. Rather I was suggesting it as a way to prototype a simpler test.

I am thinking like a software developer rather than a tax accountant. It doesn’t need to be 100% accurate, only enough to gauge rough relative pricing bands I think.

There’s not a lot of point investing months of work in something that could be throwaway, but hours or days to answer a question, or prove out a hypothesis would make sense.

The hypothesis would be that council tax rates would be fairer based on n new bands, or current valuations. This is the sort of practice I would use frequently to test assumptions.

I will see if I can find some time to look at it more this weekend.

It would be fascinating if possible….

Yes the data can be scraped.

The Review of Council Tax in 2016 was to give councils the power to design their own schemes according to their local needs. However it was quietly shelved as such the inequality that those in bands A – C continue to pay more proportionally than those in the band above – D – H.

As you suggest a LVT would be much fairer and eradicate much of the inequality.

Has anyone scraped it?

Richard – I welcome your thoughts on following.

Pls note that that its very early stage thinking, very high-level only and more of a thought that has sprung to mind. As I write this, I am fully aware of just how raw such a proposal is, it needs a lot more work and depth.

I am sharing to merely germinate a seed and cross-fertilise, and frankly get a sense of whether this has got some legs and is in line with your thinking or if you see serious issues and problems.

Given that working from home and home schooling through using technology, is very likely to be the ‘new normal’ for most people, I am guessing that home owners and others are currently looking into/or thinking about building an outdoor garden office or building an annexe, or just redeveloping existing space inside house to faciliate home office/working. If so then there could be measures and things done to to encourage this type of spending right now.

The proposal is for govt/local council to provide cash grants/incentives/reliefs (i.e. reduced council taxes) or something similar to ecourage green/environmentally friendly house development/building/contstruction, primairly aimed at owner occupiers that are considering improving/renovating, re-modelling, extending existing houses/dwellings – specifically to allow home working/home schooling. The scheme would need to fully scaleable and cover home development projects so from like buying new furniture, renovation, re-wiring for technology and just slight/minor changes through to full blown major redevelopment and building/construction work.

The objective, would be to send a clear signal that homeowners who can afford to and even if they can’t, should now spend on making their houses more environmentally friendly, this could in turn create jobs/skills in all the areas that the Green New Deal (GND) has identified as being important.

In order to benefit from the cash grant/incentive, the homeowner would need to ensure the criteria/requirements as set out by the GND standards are met, i.e. procurement of sustainable building materials, furnishings/tools, ensuring energy efficieny etc etc. This would then need to be documented and certified by a relevant body which would give some sort of undertaking that the overall development is net-zero, carbon neutral, complies with GND standards etc. The certification process would be done throughout all the stages of the development project starting from the initial planning stage to construction/development, all the way to completion.

This in turn would create jobs/skills in all the areas advocated by the GND as skills/jobs in certification, on-site inspections, enviromental friendly building techniques, use of materials, solar technology etc

Benefits for home owner would be better use of their space and allow better home working enviroment plus potential increase in value of house.

Employers could be encouraged to assist employees/workers financially for converting houses into environmentally friendly home working spaces through tax relief for both employee and employer (lower payroll taxes), homeowner could claim capital allowances on qualifying expenditure.

The home owner could also claim tax relief on some of the running expenses like under current rules and by installing using smart meteres and similar technology or undertaking other sorts of development work i.e. separate utility metres, apportionment/allocation of the amount of energy consumed in certain rooms/spaces that are exclusively used for home working should be more accurate and easy to prove/demonstrate.

A shortlist of builders, constructions, and other companies/suppliers/service companies all of which meet all the relevant standards/requirements for GND (i.e. green transport, can prove net zero supply chains as well as meeting other regulations/criteria) could be provided so that the risk of abuse is controlled. The incentives are applicable only if the approved list of companies/suppliers etc is used. This would create further skills/jobs and encourage spending in the areas identified by GND, and again the private sector companies could be incentivised accordingly through tax relief etc.

Plenty of other things to consider in relation to above, for example

– how to extend this sort of scheme/tax incentive and offer to certain landlords?

– whether to promote investment in private sector through tax releif on pensions and other saving intruments that are invested specifically in this sector/industry

– encouraging universities/developers supplying housing in student accomodation sector to adapt and provide better facilities/settings for distant/remote learning

– banks could be encorouged to lend and support financially to these types of projects

– new regulation for social housing i.e. minimum requirments to have dedicated home working space/environment

My question is that does this appeal to you or any of the readers of this blog? Is it something people would consider themselves?

I personally think this could be an area ripe for further research and development.

I think it has some merit

Others?

I did some data-scraping of Land Registry data about, ooo, 15 years ago to get an idea of how the property values in my local area had changed since the 1992 datum. While stuck at home trying to find somebody to pay me to work, I could see if I could do an update. I wonder if there are grants I could get to do this.

Grants like now are like hen’s teeth

I’ve had a quick fiddle, and the price-paid API access is a lot easier than I remember it. Should be quite easy to programatically build up a list of property values for a whole local authority. Might hit some multiple-request time limitations.

Note Chris Gilbert is also trying to do this

It would be a great exercise if possible

Richard – thoughts welcomed.

Given that income tax can be used to reduce wealth inequality, a question remains as to how to make the tax (to be perceived as) more “fair”. I’ll argue that’s more easily done using a formula rather than the current tax-bracket system.

For example, if we were to use a polynomial of the from T= aI^2 +bI +c, where T=tax and I=income (and I^2 means I squared), if a and c are made zero, b is a tax rate that makes tax linear with income. Visualized graphically, it’s a straight line.) Everyone from top to bottom pays tax proportional to their income. Hard to argue that’s not “fair”,

If we wish to exempt low incomes from tax, the constant c can be made negative to position the zero tax point at whatever level of income is desired. (Visualized graphically, it’s just moving that straight line to the right.) Some may object to some paying no tax, but the amount is clearly shown and it applies to all incomes, top to bottom.

If we wish to shift the tax burden so that high incomes pay more and low incomes less, increasing a bows the straight line to the right. Some may argue that taxing high incomes at a proportionally higher rate than low is “unfair”, but again the effect is clearly shown (and played with using pencil and paper or any of the online graphing sites) and applies universally across the full range of incomes.

In short, using a tax formula can reduce suspicion that the wealthy are gaming the system.

First, I don;t recognise your formula in tax

Sew coins, you conveniently forget to define a and c

Nor do explain why I squared would have a role in tax

And having forgotten to do all that you then claim that this justifies a flat tax – which is very, very far from fair because you have conveniently forgotten marginal utility theory – which happens in this case to conveniently approximate reality

I am not in the slightest bit impressed

The impression that you are here to troll remains

The bold b in the 3rd paragraph was a test to see if web coding could be used

in these comments. It looks like letters/words/phrases can be emboldened by

bracketing with and .

They can be