![]()

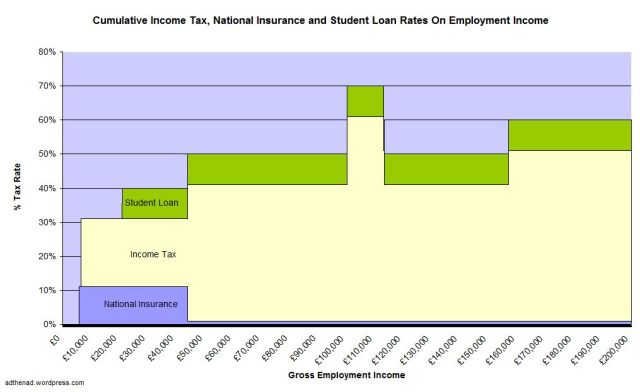

A valuable diagram has been put on line regarding the effective tax rates students will suffer as a result of student loan repayments.

The graphs are not by me, but by ‘adthenad’ who produced the blog they come from and who, I assume, has opted for anonymity.

It shows the marginal tax rates those repaying student loans and other people will face under the new regime (although I’d add, these aren’t so very different from the existing one except they’ll endure a lot longer in many cases as the absolute amounts to be recovered will be so much higher):

Now we can argue forever about whether tax is a disincentive to work, or not. I happen to think it probably is — but only when tax rates persistently above 50% at higher rates of income, although accept that this can also be the case at lower tax rates when income is lower. In other words, the disincentive effect is related to rate and income, and the disincentive effect may well be greater when income is lower. There’s nothing radical in saying that — this is an argument for steadily progressive taxation and I stress, this is based on observation and my interpretation — nothing more.

More important, those introducing this policy do believe that tax has a disincentive effect — Cameron and Osborne (who have never had to worry about these things and appear not to have an iota of entrepreneurial spirit between them) say that tax is an impediment to enterprise, often.

Why then are they creating a situation where a person can have an effective 40% tax rate at just over £20,000 of income? And note that this will rise soon to 41% soon when NI goes up — the exact same rate that many ministers pays on their vastly higher salaries?

They might also like to discuss the impact on future entrepreneurial activity, risk taking and even tax evasion of persistent 50% tax rates for those in the £50,000 - £100,000 range who are often inclined to create new businesses.

And they might even want to consider why there’s almost no chance at all, of course, that the rate of 60% will be paid by those earning over £150,000 because they’re most likely to leave university with no debt at all as they’re most likely to a) have parents who paid in full so they have nothing to repay or b) have debt that is repaid in shortest duration and with lowest marginal impact on well being.

If the Tories and Orange Bookers really believe tax is a disincentive then sure as heck they’re doing their best to make such disincentives real.

And all to ensure that the wealthiest stay wealthiest. It is hard to see it any other way.

NB — even harder when you read this which seems indicative of the same deliberate policy of exclusion.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

“Now we can argue forever about whether tax is a disincentive to work, or not. I happen to think it probably is — but only when tax rates persistently above 50% at higher rates of income.”

Am I to conclude that tax rates of 50% and higher are a bad idea?

given that a student loan is not a tax, then repaying it has no impact on marginal tax rates.

interesting that Ed is in favour of a graduate tax but Dave and Nick aren’t.

Richard

This graph and these marginal rates are nothing new for those of us who graduated in the last 10 years, except that at present we have a 40% marginal rate for earnings above £15,000 and under the new system, there will instead be a 41% marginal rate starting at earnings above £21,000.

Ken

@alastair

But it doesn’t really behave like a loan does it? The payments are income related. That looks like a tax to me. It’s a bit like those finance leases that call themselves leases but when you get down to the fine print, it’s really a sale not a lease.

As Shakespeare said “A rose by any other name….” or as he didn’t say “A crock of shit by any other name….”

fyi

OECD — Paris, 8 December 2010

Tax reforms to improve economic performance

Many governments are facing historic high levels of deficit and debt. Public spending has risen and they are taking in less money as tax revenues fall – more than 10% in some countries.

Governments are attempting to consolidate their budgets, looking for the appropriate balance between expenditure cuts and revenue increases. The OECD’s “Tax Policy Reform and Fiscal Consolidation” says that for tax regimes to support sustainable economic growth, governments must decide the right way to raise additional tax revenues.

Taxes can be a disincentive to work, invest and innovate, with adverse effects on economic growth and welfare. But these such distortions can be minimised:

¬? Change the overall tax structure to raise more revenue from taxes on consumption and residential property tax and less from personal and corporate income taxes;

¬? Broaden tax bases to enable rates to be kept as low as possible;

¬? A “green” tax system, crucial to a Green Growth strategy, will achieve environmental objectives and the additional revenues raised may facilitate wider growth-oriented tax reforms;

¬? Ensuring that all citizens pay their fair share of taxes contributes to fiscal consolidation. OECD initiatives to counter offshore non-compliance are yielding billions of euros in extra tax revenues.

These arguments are further explored in two Tax Policy Studies.

Tax Policy Study No. 19 details the rationale for tax breaks, asks whether they are still justified, and cites case studies such as VAT reduced rates and tax reliefs for house buyers. It notes that ”tax expenditures” are often entrenched in tax regimes and urges countries to evaluate whether they are worthwhile.

Tax Policy Study No. 20 recommends ways to make taxes less distortive and more growth-friendly. It also looks at the “political economy” of tax reform — why governments are able to design, legislate and implement growth-oriented tax reforms in some circumstances and not others and how to overcome obstacles.

Tax reforms will only work if taxpayers agree they are fair. For example, reforms that recycle some of the additional revenues to poorer households can be helpful. Governments must consider the distributional impact of the whole tax reform package — balancing the impact on taxpayers against future growth prospects and ensuring that all taxpayers continue to pay their fair share.

More information about these publications, including executive summaries, is available at http://www.oecd.org/ctp. The OECD will release new data on tax revenues and tax-to-GDP ratios on Wednesday 15 December in the 2010 edition of the annual “Revenue Statistics”.

For further information, journalists are invited to contact Lawrence Speer on + 33-1 45 24 79 70.

Hold on a second. Didn’t some minor economist called Laffer (first name Arthur) work on this assumption some time in the early 1970s and develop a curve based on it? I thought we had agreed the whole thing was a fraud.

@alastair

And that is clearly why the government favours using students loans instead of raising the rate of income tax. It behaves in exactly the same way, is a tax in all but name and imposes itself more upon poor people than rich.

It seems the government would do anything to avoid changing the main income tax rates, and is again raising national insurance rates in 2010/11, which doesn’t have any effect on incomes above £44,000.

Just because it is not called a tax does not mean it isn’t in any true and fair sense of the word, it is just PR.

That should say raising National Insurance rates in 2011/12.

@Adam Hehir

it imposes itself only on people who took out the loan, and only once they reach a pre-defined income level. income = earnings, not wealth. I suppose you could argue that the prescription charge is also a tax.

@alastair

You know, we could also introduce tuition fees for primary and secondary education. It wouldn’t be a tax since people’s parents could pay. Of course if they can’t afford it, and the children have to take out a loan, well they did have a choice there. The most important thing is we don’t have to put up tax rates on the rich, or change the main rate of income tax.

Since repaying a loan is not a tax, who cares that it falls upon poor people?

@Adam Hehir

what a strange argument. I suppose we could, or at least parliament could. but what relevance this has on higher education is not entirely clear. Perhaps you might expand?

But I do think you have misunderstood the repayment bit. It falls on people who took out the loan and then meet the criteria to start repayment. how poor you are is irrelevant.

@linda kaucher

That’s a rich source of information you have pointed to. Thanks.

I’m summarising madly here, but it seems to be saying that societies seeking to promote standards of living (which is most of us) should:

1) increase VAT, probably to the 25% level seen in Scandanavia, and eliminate VAT exceptions

2) Introduce a land tax (again like Scandinavia); and most relevantly for this thread

3) reduce Corporation tax

The OECD’s prescription then is kind of saying that the Scandanavians have the best tax model, which is almost the mirror image of the UK Labour Party position (certainly on points 1 & 3).

I hadn’t actually twigged before that the Labour Party held the Scandanavian model in such high regard in theory but actually argued against implimenting it in practice.

http://browse.oecdbookshop.org/oecd/pdfs/browseit/2310131E.PDF

@Gary

Yes, but for heaven’s sake – let’s realise the OECD is part of the Washington Consensus which prescribes the Treasury View

Which is wrong

Anyone who disagrees with it is on the right lines on such issues

Being slaves of defucnt economists, as the OECD is, is not a a sign of credibility

@alastair

Not at all

I think it’s 100% spot on

In absurdum it proves how crazy the logic of tuition fees is

@Richard Murphy

Fine, let’s accept for the moment that the OECD is in the pocket of the Global NeoCon Conspiracy ™.

My point remains – the scandanavian model combines high levels of VAT and a land tax, which funds a lowering in other taxes that promote growth.

The Labour Party in the UK regularly points to scandanavia as a role model for us. If that’s true, then why do they argue the very opposite when it comes to the practical implimentation such as raising VAT?

@alastair

The relevance it has to wealth levels are as follows:

If you want to go to University, either

1 your parents can pay for you, which can only happen for people privileged enough to have wealthy parents, and who also agree to pay,

2 you take out a loan to cover the fees and living expenses or

3 you can afford to pay for yourself, which at £27K just for fees for 3 years, not including living expenses is outside the reach of the vast majority.

So we’re setting up a system that means if you want tertiary education, you either need to come from wealth or take out the loan, which therefore falls heaviest on poor, and effectively becomes a tax on poor people.

Earning enough to pay for fees and living expenses while at university is extremely unlikely. In most cases, it would be in fact impossible as can be seen from unemployment rates of young people. There simply are not the jobs for the 50% of people who currently go to university to work at the same time to make this suggestion feasible.

University should be for the best and brightest and not just for the rich. Anything else reduces social mobility and is the opposite of what this country should strive for.

@Adam Hehir

I agree entirely that university rationing should be based on ability, and I would completely support a proposal to return to the kind of grant based system that applied when I went to university. Although the same sorts of issues in terms of “wealth”, or actually “parents wealth” applied then as it does now. After all, as I remember I left university with a rather large overdraft, and had to pay it back from a very small wage.

@Gary

You ignore the fact that Scandinavians have regressive tax systems (they do) and massively progressive benefits system

Don’t view these things selectively

This comment has been deleted as it did not meet the moderation criteria for this blog specified here: http://www.taxresearch.org.uk/Blog/comments/. The editor’s decision is final.

@James from Durham

no, the payments are loan related – it is the requirement to make them that is income related.

@Richard Murphy

“Finland, Norway, Sweden and to a lesser extent Denmark introduced a dual income tax system in the early 1990’s. The purest dual income tax system has been established in Norway. The main characteristics were:

1) A flat personal income tax rate of 28% on net income

2) Progressive taxation of wage and pension income in addition to the flat rate above a threshold level. The highest surcharge rate was 13% in 1992; it increased to 19.5% in 2000 and decreased to 15.5% in 2005.”

So its tax system is regressive except for the progressive taxation on higher incomes of 43.5% ?

http://www.oecd.org/document/45/0,3343,en_21571361_44315115_46639597_1_1_1_1,00.html

@alastair

Although I would imagine your rather large overdraft was less than £27,000 plus say an extra £10,000 living expenses? And you could have discharged it through bankruptcy. And had your income remained less than the national average you wouldn’t have been paying back your overdraft at 9% on top of income tax for the rest of your working life.

@Gary

When talking about Scandinavian countries it really should be remembered how much lower the wealth disparity is there. Higher VAT rates weigh heaviest on the poor, however if wealth disparity is low enough the impact does not matter as much.

The income inequality is so much greater in the UK, putting up VAT here really does hurt the poor disproportionately.

If we reduced the wealth disparity to Scandinavian levels then I would probably support a higher VAT rate, but until that happens I think it is a very bad idea.

@Gary

I repeat – look at the system as a whole…..all taxes – not just income tax

@Richard Murphy

Yes you do repeat – I must indeed look at the entire tax system as a whole.

Let’s do that. I have so far covered Income Tax, Corporate Tax, VAT and Land Tax in this thread. But of course that is not the whole picture. On closer examination Richard is indeed correct – I have only covered 81% of total tax reciepts(http://browse.oecdbookshop.org/oecd/pdfs/browseit/2310131E.PDF)

My apologies for reaching conclusions while missing 19% of the available data.

The balancing figure of course being Social Security taxes, levied proportionately as per almost every other developed country on earth. Indeed regressive, but no more so than any other covilised country. They defining element of most countries progressivity remains its approach to Income tax, which is markedly progressive in Scandanavia.

So my question remains: if Scandanavia is in theory thought to be a role model by the Labour Party in the UK, why are the the practical steps to achieving that nirvana resisted by that same party? We know the path to the Scandanavian heaven – why not take it?

@Gary Taylor

But I said ,look at their benefits system

It’s massively progressive to counter the tax system

Have you done that too?

I think not

@Gary Taylor

Please take a look at the graphs showing the massively different levels of income inequality between the Scandinavian countries and the UK, and the different metrics they are measured against from the tax justice website on the link below. I’m having trouble posting the link, possibly as it is a PDF file so I’ve put the link through my blog.

http://adthenad.wordpress.com/2010/12/09/wealth-disparity-graphs-on-the-tax-justice-website/

Which policies are you proposing are copied?

Also copying policies verbatim wouldn’t necessarily result in forging the path to Scandinavian heaven, as we are starting from a different position. As per my earlier message, raising VAT before reducing the wealth disparity is a bad, regressive policy.

By the way I personally think raising land taxes would be a great idea.

Richard,

One must admit that, at face value, your replies to Gary do not add up.

Gary has demonstrated that the Scandis have a highly regressive taxation regime, whereas the UK is by and large progressive. (Gary, how do you find the time to write all these thought-provoking entries?)

If I understand correctly, you argue that the Scandis’ benefits are so much more progressive than in the UK that their net tax-benefits system is equally progressive, or more than in the UK.

It is difficult to get comfortable with this after accounting for a number of facts (or at least strongly held intuitions):

One is that the percentage of the population living in relative poverty, and therefore eligible to receive long-term welfare benefits is lower in Scandinavia than in the UK.

Another is that the Scandis’ famed family benefits (extensive childcare, etc.) are not means-tested.

Further, there is the fact that in the UK healthcare and education (two main components of government spending) are spent predominantly on lower income recipients with higher income massively favoring private provision of these services (one does not see many high-earners in NHS wards or sending their kids to public schools).

Contrast this with the fact that the public healthcare and education is much more prevalent in Scandinavia, making the benefit system therefore much more regressive.

Maybe I am missing something. Could it be that the pensions system is so progressive that it even this out?

If this is the case, you will no doubt point it out in a reply which I expect will be courteous and constructive, as per your own commenting guidelines.

@Richard Murphy

Yep – your right again. I’ve checked with the Swedish Statistics Board, and their benefits system is indeed highly progressive, with nearly 30% of GDP invested in it (1).

So now we have been all the way round the block with an analysis of both the tax and benefits systems, my original question remains: The Labour Party in the UK often points to the Scandanavian model as something we should aspire to. Yet somehow it resisted taking the steps to implimenting it, instead argueing for the very opposite in key matters such as VAT and Corporate Tax.

(1) http://www.scb.se/Pages/PressRelease____294038.aspx

@Adam Hehir

in real terms it was probably similar. And of course you are ignoring the opportunity cost of all that lost income, although at the time my chosen career path required a degree as a condition of entry.

not sure where the bankruptcy thing comes from. I guess you are suggesting that it is not a way of avoiding the student loan? I know it does not have the stigma now that it used to have, but it is not a path I would consider taking.

@Gary

So Labour’s got it wrong?

I’m not here to defend Labour

Your next problem is?

@Adam Hehir

I’ve just had a look at the graphs. Thanks for that.

To your question: I take it as a given here that the Scandi model is something to aspire to. Your graphs give us some indications why that is so desireable, but they dont say how to go about it.

Now, the most potent levers of social engineering are often around tax and spend. The Scandi model says, in essence, that we like saving, investing, generating capital, generating profits and reinvesting profits. We don’t like wasteful or frivolous consumption. So the things we *do* like have low taxes, and the things we *don’t* like have higher taxes. Its not rocket science this stuff.

The really good news though is that, with that combination, we can create high levels of GDP/capita, and and skim some of that to invest in a big welfare state, generating some of the graphs you point to.

So what policies would I adopt? Pretty much all of them. Let’s debate the timing, the transition plan, the order of events, etc. But let’s not go right off and do the very opposite. Let’s not lower VAT and raise CT for example.

I like very much what the Labour Party in the UK says (let’s get a high growth Social Democratic model likes the Swedes), but not what it does (builds an illiberal authoritarian state machine that punishes wealth creation and rewards feckless over consumption).

And I genuinely don’t get the disconnect. I’m not being flippant or sarcastic. It’s not a trick question. How can the Labour Party identify a terrific role model, have perfoect visibility of what needs to happen, get 13 years in power and go do the very opposite?

@Million Dollar Babe

Crass analysis – learn something about income distributions

You may think the world is full of rich people

&% of kids go to private school

Fewer to private hospital

All emergency cases go to the NHS

Your ability to appraise data is so flawed debate is pointless

@alastair

So your overdraft was similar to £40K in today’s money, and you didn’t have to pay tuition fees, though no mention if you actually received a grant on top of that? I can see why you must think today’s students are living it up on the tax payers’ expense!

I’m not sure what you are referring too specifically when mentioning the opportunity cost of lost income. Anyone who goes to University forgoes that lost income, although considering the rate of unemployment of young people today I guess it could be argued they have a lower opportunity cost of lost income since it may otherwise be £0, or however much they would get on the dole.

@Gary

You seem to have missed the fact the New Labour were a bunch of right of centre neo-liberals.

How?

@Adam Hehir

How pessimistic is that? Actually one or two of my school chums went into banking – some into the entertainment industry – one or two got proper jobs with on the job learning. They were all earning a lot more than I started on when I graduated. That is a lot of opportunity cost!