I have been asked for a blog post explaining the double-entry that explains the money creation in the central bank reserve accounts that commercial banks hold with the Bank of England and apologise for the delay in delivery: this took more time to write than I thought it would. The full post is below, but for those who would find it easier there is also a PDF version, here.

I have already written a note about what the central bank reserve accounts that commercial banks maintain with the Bank of England are, and how they are funded. However, that note could not answer every question that comes up with regards to these accounts, and in particular how they operate on a day-to-day basis.

I understand that there are real conceptual issues in understanding how it is that the base money that is created day in and day out by the Bank of England to let the government spend in fulfilment of its policy decisions within the UK economy can, nonetheless, be wholly ring fenced within the central bank reserve accounts maintained by the commercial banks with the Bank of England. Put another way, the question people struggle with is how the £900 billion or so in the central bank reserve accounts of the commercial banks at the Bank of England never transfers over from those accounts into the commercial banking sector, and similarly, why commercial bank money never transfers into the central bank reserve accounts.

The conceptual problem in understanding this does, I think, result from a lingering belief that most people have somewhere deep down inside them that there really is something physical and tangible that they might actually touch which represents money. That, however, is completely untrue. Even notes and coins are simply physical representations of an intangible promise made by the government to pay whomsoever might hold them as property at any particular point in time. They have no implicit value in themselves and yet it seems very likely that people do think that that there is a movement of some form of tangible property between bank accounts when payments are made and received between accounts.

This note seeks to explain why that is not the case and to demonstrate how government spending can both create central bank reserve account balances and simultaneously increase commercial money supply even though the base money and commercial bank created money remain quite separate, one from the other.

To explain this assume that the following quite simple series of transactions takes place:

- The government wishes to pay Freda Davis her old age pension of £1,000 for a month. Freda banks with the Nationwide Building Society, which is a bank for these purposes;

- When she gets her pension Freda transfers £400 of that sum to her husband, Thomas, who banks with Lloyds;

- Freda then discovers that tax should have been deducted from the pension payment made to her and as a result makes payment to HM Revenue and Customs of the £200 tax liability that she owes on the pension that she received.

This seemingly everyday set of transactions gives rise to a great deal of activity behind the scenes. I will try to include reference to only those transactions that are strictly necessary to make clear what is happening apparent. The reality would be more complicated, but explaining why will add little more value.

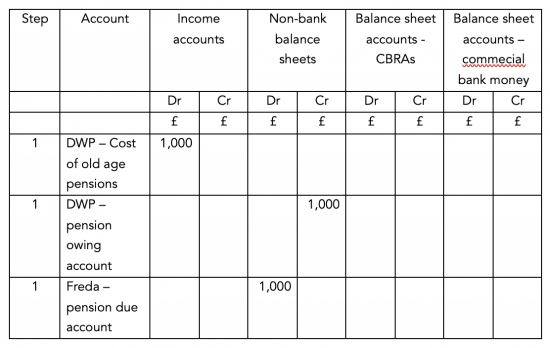

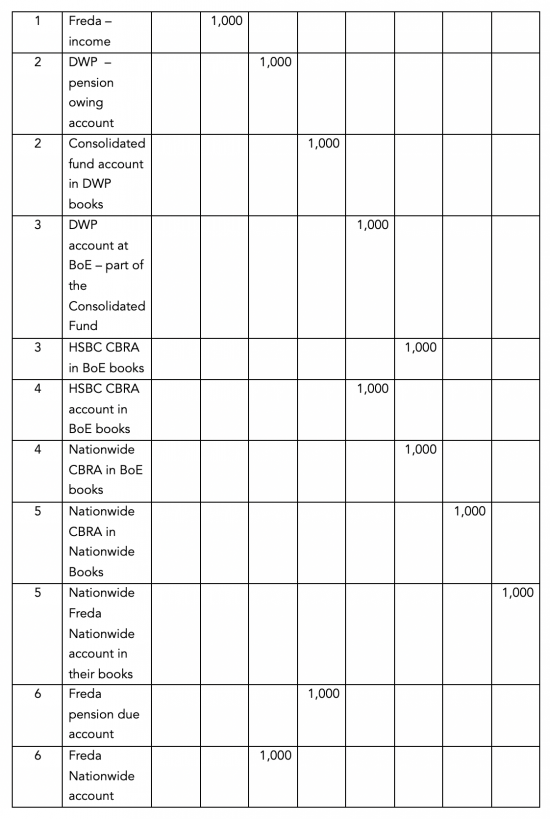

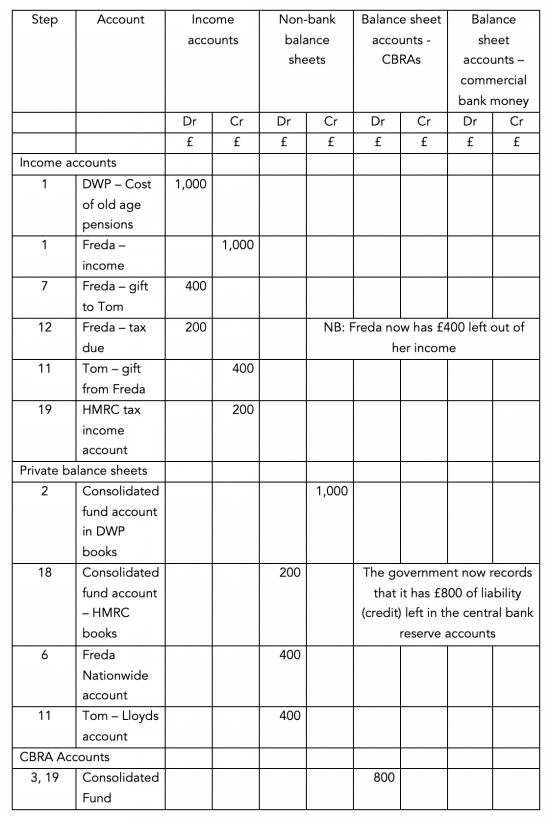

First of all note that the payment to Freda is the settlement of a debt that the government has created to Freda. They have agreed to pay her each month, and she anticipates them doing so. It is this promise to pay that sets up all the transactions that follow. To record this debt the government debits its cost of old-age pensions paid account in its income statement and credits its pensions owing account on its balance sheet. If Freda kept double-entry books she would debit her pensions due account on her balance sheet and credit her income statement with the £1,000 pension income. This is step 1.

The next task (step 2) is for the government to settle this liability. To do this the DWP instructs the Bank of England to make a £1,000 payment through the Consolidated Fund to the commercial bank that makes payments on behalf of the Department of Work and Pensions. I will assume that is HSBC. So, the DWP records a reduction in its pension owing account (a debit) and a credit in the records it keeps of its account with the with the Bank of England. Both are for £1,000.

Of course, the Bank of England has to also record that transaction in the Consolidated Fund of which the DWP forms a part, but from its perspective this transaction is a debit – the government owes that sum to it. There has to be a credit to match, and there is: the Bank of England credits the HSBC central bank reserve account. Each sum is £1,000. (Step 3)

To simplify matters here (to save noting a lot of transactions in the bank's own books to record inter-bank transfers), let us assume that HSBC immediately realises that the payment request it has received attached to the funds placed in its CBRA is not one that it can process – as the sort code on it will make clear. So, it transfers the funds straight on to the Nationwide CBRA in step 4.

Now, albeit indirectly, the Nationwide has £1,000 from the DWP lodged in its CBRA. It has an obligation to pay Freda as a result. This it does with commercial bank money. It accepts the debit in its books from the CBRA – the promise to pay from the government – as the guarantee and backing for its own promise to pay Freda – which it creates by recording the £1,000 owing to her as its liability (a credit) to her. (Step 5).

Freda completes this stage of the transaction in step 6. She credits her pensions due account on her balance sheet and debits her Nationwide account in her books, again for £1,000 in each case.

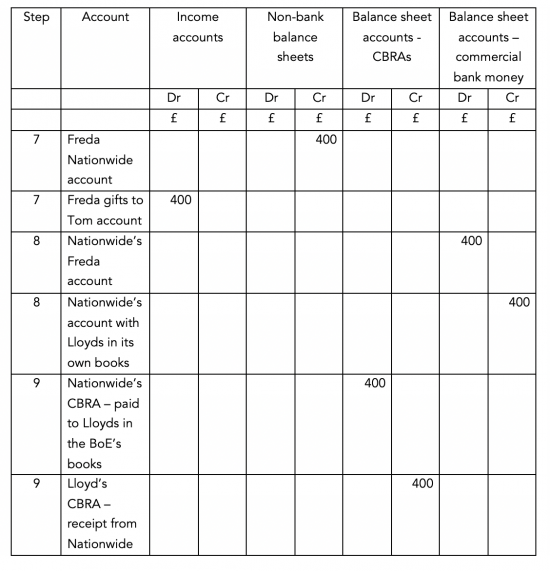

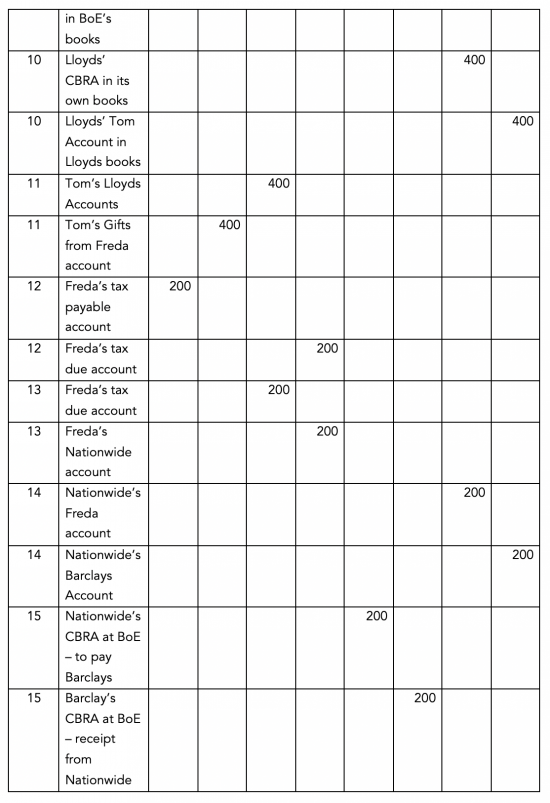

So, to this point we have these transactions:

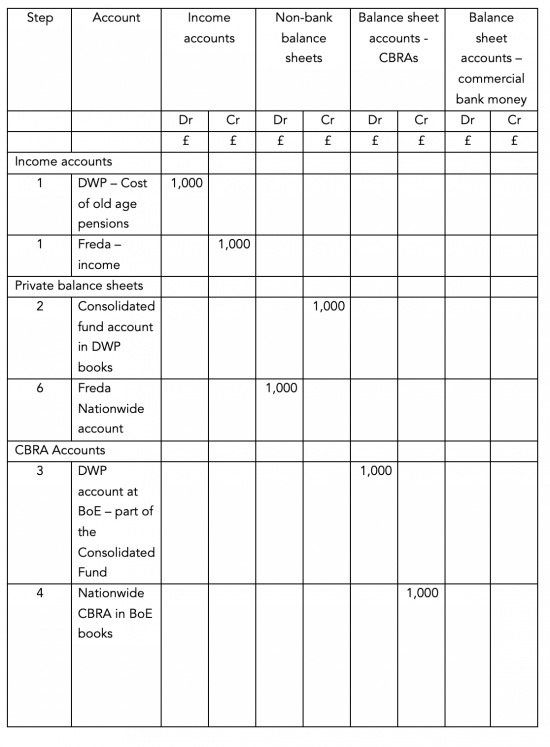

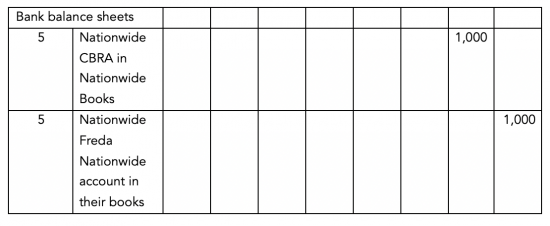

To summarise to here, we have these transactions recorded when all transfers and account balances owing are taken out of consideration if they have been matched during this series of entries:

The DWP has paid Freda, and both base and bank money have been made on the way to doing so, without the two in any way cancelling each other out. Note that the double entries match in each pair of columns and especially that there is no leakage into or out of the CBRAs where instead the transactions are matched by those in other records to record the obligations recorded there.

This, though, is not the end of the transactions. Freda now has to pay her husband £400 to be paid into his Lloyds account, and to pay HM Revenue & Customs £200. To continue from where we were then, in step 7 Freda issues an instruction to the Nationwide to pay Tom. She credits her own record of her Nationwide account on her balance sheet and debits her ‘gifts to Tom' account to record the spend.

In step 8 the Nationwide deducts funds from Freda's account and records the fact that it now owes this money to Lloyds so that they can pay Tom.

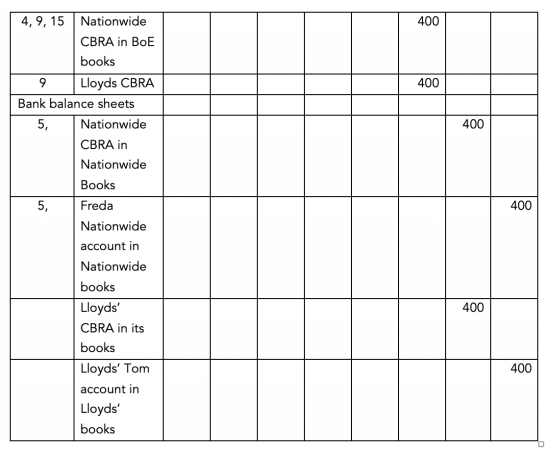

In step 9 the Nationwide pays Lloyds via its CBRA.

In step 10 Lloyds acknowledges the receipt in its CBRA from the Nationwide and as a result records that it now owes Tom £400 by crediting his account.

Tom finally completes this transaction in step 11, recording as a debit the increase in his bank account and crediting his income account with the gift from Freda.

In step 12 Freda acknowledges her tax debt and in step 13 tells the Nationwide to pay it via Barclays, who collect bank payments on behalf of HM Revenue & Customs.

In step 14 the Nationwide deducts £200 from Freda's account with them and acknowledges it now has a debt to Barclays for credit to HMRC.

In step 15 the Nationwide pays Barclays via the central bank reserve accounts.

In step 16 Barclays records the resulting debt from the Nationwide as a debit and that it now owes HMRC as a credit.

Step 17 acknowledges that this debt to HMRC will be paid via the CBRAs by making the necessary adjustments for that in Barclay's account before in step 18 the funds are debited as a charge in Barclays' CBRA and credited to HMRC's CBRA account.

Finally, in step 19 HMRC records its income of £200 and that it now has £200 more in its CBRA. The record is complete.

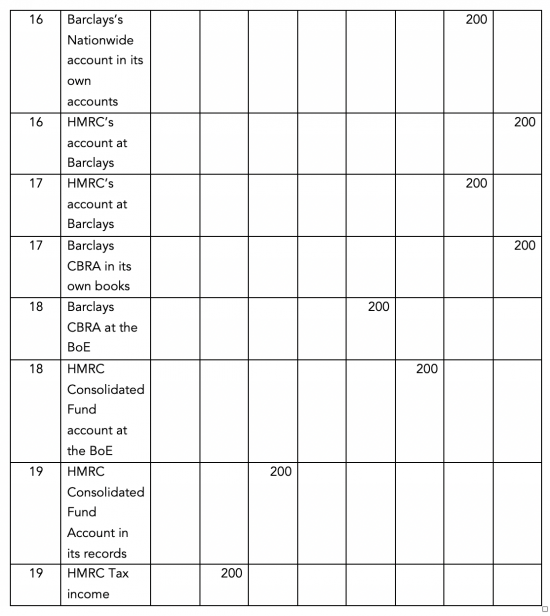

Netting all these transactions out we now get:

A net £800 of new money has been created via the inflation of the central bank reserve accounts through government spending, which is reflected in the balances of the Nationwide and Lloyds even though originally paid to HSBC.

To match there is £800 of new commercial money created by those same banks, with Freda and Tom being the beneficiaries of this.

Of the original £1,000 of new money created £200 has been cancelled by the payment of tax.

That's how the central bank reserve accounts work.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

All very good , great that you make this effort.

A couple of points I think may help put this is perspective. Firstly banks can create their own commercial money when they make loans, but they can never create CBRA’s. I like to see that as froth on top of the CBRA system, CBRA’s being the highest tier or safest/strongest money we have. The amount of commercial bank money in existence(total money in bank deposits) can and does vary considerably over time. Commercial bank money is however confusingly allowed to take on denomination in pounds Sterling under the power of its bank licence, that is, it is allowed to take on the same status of CBRA’s despite being obviously inferior money.

The amount of commercial money in bank accounts went up 4 fold from 1990 to 2008, increasing from around £500 bn to over £2200bn due to of the increase in bank lending over that period(for property/stocks loans mainly). At the same time the amount of CBRAs remained pretty much the same, hovering around £60bn over tne same period (as a comparison. )

The banks can add plenty of froth on top on top of the CBRAs , which at the end of the day are what the banks use use to pay one another. No bank can pay another bank with this commercial money and individuals and businesses cannot use CBRA’s whatsoever, to make payments their bank has to do this for them using the CBRA system.

The BoE in effect acts a banker to the banks using CBRAs and although the two systems work in tandem, they are two closed loops. The bank netting out process removes the vast majority of interbank payments before its is finally settled in CBRA’s at the end of each settlement period, which is several times a day I now believe. Though I do see money being transferred immediately to other banks accounts via my banking app, I have no idea how they do that so quickly nowadays.

Back to the interest paid on the CBRAs. This creates yet more Base Money, and increases the bank’s capital if they retain it as profit, but I don’t follow the point Clive made about needing to pay interest at Base Rate in order to control interest rates across the economy. I see exactly that as Base Rate is the rate at which banks can BORROW from the BoE, then no bank is going to lend at anything less than Base Rate + X% in order to ensure they have a margin. I realise banks don’t borrow BoE money in order to lend it out. They may, though, need overnight or potentially longer term loans from the BoE to balance the books at the end of the clearing day. I plan to check on the BoE web site as there should be details of what, if anything, they are doing in terms of lending. Even if the current very high CBRA deposits mean the banks have zero need for any short term funding, they still ‘might’ need it some day. So they would still always want to have a decent margin above Base Rate for their lending to customers.

On the other hand what does paying Base Rate on CBRA deposits achieve? Banks do not pass this on to customers in terms of them paying interest on current account balances and there is no requirement for them to do so. I do not see why this profit windfall for the banks would have any effect on the rates the banks lend at. In fact it could have an inverse effect. Lets suppose Base Rate was 10% meaning the banks were getting £95 billion pure profit out of the CBRA balances. They could actually then afford to make loans with a smaller margin above Base Rate since they would not need the profit. The banks can’t increase or decrease their CBRA balances individually, so it is not the case that a higher interest rate might attract CBRA deposits and a lower one reduce them. Reducing lending to increase their CBRA balances does not work, so that can’t be an effect. The only thing I can see is in terms of the relationship between CBRA balances and Gilts. Selling a gilt reduces the CBRA balance and vice versa. Also using the CBRA balance to buy a gilt is about the only thing the banks can do with this Base Money. So if Base Rate was say 4% and gilts paid 3% then clearly banks would be incentivised to sell the gilts and move the money back to the CBRA. So that would suggest the rate on new gilts would always have to be higher than the rate paid on the CBRAs, otherwise all the banks (and anyone else with a BoE account such as foreign states and central banks) would refuse to buy gilts. So I think the interest rate on CBRAs will have effect on the cost of borrowing for the Treasury on its gilts. Does the rate on gilts have any effect on bank lending rates on e.g. mortgages? A higher Base Rate / gilt rate will, as can be seen, have some effect on exchange rates, since foreign states / central banks may choose to increase the sterling reserves they hold (they hold about £560 billion (mostly in gilts or corporate bonds) according to the latest IMF data).

Surely the controlling effect on interest rates across the economy of making changes to Base Rate is actually because most banks structure their lending rates as Base Rate + X% e.g. tracker mortgages, and not because of any interest paid on the CBRAs?

As far as I can see bank overnight repo has pretty much ceased so I do not think you will find what you are looking for

CBRAs changed that

I think Clive is right – but NEF have appropriately refined the argument in a way I had also discussed – i.e. tier the sums paid

Interest rate markets are all a ‘relative value’ game. A pension fund will judge a corporate bond investment versus a gilt (of similar maturity). If banks can earn more on gilts than CBRAs then they will buy gilts that will depress gilt yields and in turn, depress corporate bond yields.

All these rates are linked and if excess reserves are unrenumerated it will filter through to all market rates.

Until 2008 all the ‘action’ was at the offered side as the BoE added reserves to prevent rates rising too high. Today, excess reserves mean that policy interventions happen at the bid side and currently that means paying interest on excess reserves.

Our challenge is to get policy rates transmitted to the real economy without rewarding banks unnecessarily.

1. Require by regulation that banks hold more unrenumerated reserves.

2. Require them to pass on higher rates to customers.

3. Tax them differently.

4. Any other ideas gratefully received.

“All these rates are linked and if excess reserves are unrenumerated it will filter through to all market rates.”

Since this, on any reckoning is ‘money for old rope’, if 0% was paid on CBRAs, how precisely would that filter through to “all” market rates, and particularly in what sequence?

I think that is a fair question.

I see the use of the CBRAs for controlling short term rates

I simply question that we need £900 billion for that purpsoe

Other countries do not

Many, many thanks for this invaluable detailed analysis Richard. I shall not comment, because I wish to read it carefully and reflect on it.

Rarely have I spent so long on a single blog post

Crumbs! It is clear I was never cut out to be an accountant. Double entry doesn’t clarify things, it complicates them.

It’s a language in its own right

I admit this took some thinking about

It was worth doing…..

It proved that double entry dies create and record money

First, this all suggests that CBRA balances are for ever upward. (Unless we really are taxed to destruction).

Second, isn’t this a most elegant example of the government creating money as it spends and destroying it as it withdraws it through tax?

But remember, tax does largely balance spend, and inflation control demands that, plus I ignored deposit taking (borrowing)

Incidentally, I do not know whether this and some of the earlier threads on CBRAs and CBRA interest will find their way in some form or other into the book you are currently writing (between 2am-6am each day?); but if not there, a consolidation of the CBRA themes pulled together in a single PDF would be an invaluable resource (okay, um: midnight-2am?).

I will consider that….

I see the reason

If there’s someone who wants to volunteer to edit them together, even better

Would be happy to help IF I were at my desk…… but currently away sailing….and couldn’t manage it on my phone.

It can wait….

Splendid! What a supportive community Richard’s Blog possesses.

There was an item on Radio 4’s More or Less programme this morning, exploring the question of whether or not the government could have “saved” £11 billion of debt interest payments. About 6 minutes in here. https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/m0018gql

That was in response to reports like this. https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2022/jun/10/rishi-sunak-wasted-11bn-by-paying-too-much-interest-on-uk-debt

From about 7:30 seconds, Tim Harford starts by explaining that the Bank of England “printed lots and lots of money and used it to buy bonds” from commercial banks as part of quantitative easing; that the commercial banks “who sold all the bonds to the central banks” needed to find a safe place to deposit “their quantitative easing money”, which is at the Bank of England; and the Bank of England pays interest on that £900 billion, because “that is how bank accounts work”.

The underlying story was about NIESR’s proposal last year to refinance hundreds of billions of QE and COVID debt at low rates, but on the way I think this explanation fundamentally misunderstands how quantitative easing works, and more importantly what these reserve accounts are actually are. It completely elides the question of whether or not the Bank of England needs to pay interest on its reserve accounts. (Even if these were like normal bank accounts, which they are not, I have had many bank accounts that do not pay interest, and there are many bank which require the account holder to pay for the privilege.)

There is the completely separate question of how much interest the government actually pays away each month, given (1) so many gilts are held by the APF which returns the interest to the Treasury, and (2) so much of the “interest” booked each month is accruals for liabilities on index-linked bonds that won’t be payable until redemption.

That, if I might say so, is Tim Harford for you

I very much doubt he gets the macroeconomics of this at all

What an epic post. I’m really grateful for the effort.

The payments seem staged in a way to guarantee/underpin the payment.

And that money being used in the real world of mortals has to be backed up by that shadow promise/guarantee.

The money exists in as much as ay each stage through the distribution system including the CBRA there is a ‘passport’ or promise to pay it.

And it reminds me that accounting is surely as much about meeting an obligation to pay – not avoiding it!!

But this to me is also a more authentic way to ‘balance the books’.

I hope I got that right.

Thanks once again.

You seem to have got it to me