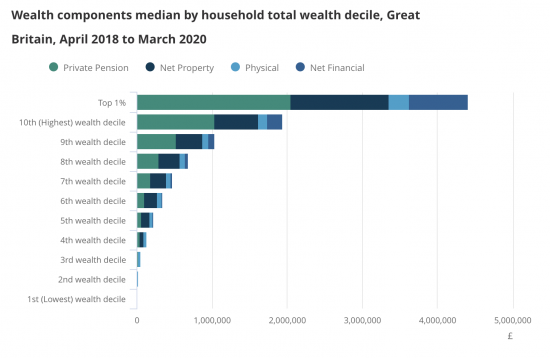

There is nothing especially surprising about this distribution. The fact that the UK is a deeply unequal society that is massively skewed towards wealth being concentrated in the hands of relatively few people, is not news.

There is nothing especially surprising about this distribution. The fact that the UK is a deeply unequal society that is massively skewed towards wealth being concentrated in the hands of relatively few people, is not news.

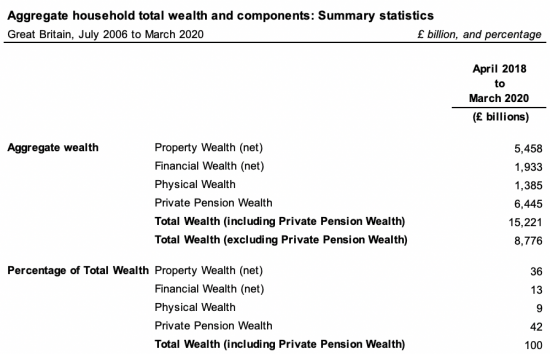

Data at the aggregated level is, however, more interesting to me. Data at this level is only available in a downloadable spreadsheet, with no attached press release, but it is a benefit that the spreadsheet in question does include data from 2006 onwards, which represents the entire period over which the ONS has been collecting this information.

Note that this data is stated net i.e. liabilities are matched against assets, which is particularly relevant with regard to personal financial wealth and property.

It is useful that the same categories of allocation are used within the personal data set noted above. What is particularly relevant is that 55% of total UK wealth is financial, with 42% being held within pension funds and 13% as personal financial wealth.

Of the latter, which represent about £1.9 trillion in total, about £700 billion is held in ISA accounts, based on ISA statistics. These are of course tax incentivised savings accounts, which is also a fair description of what pension funds are. It is also the case that the vast majority of household ownership of property also enjoys significant tax incentivisation because there is no capital gains charge on the accumulation of value that domestic homes have accrued over time. If this combination of property, ISAs and pension funds are taken as a single group of tax incentivised assets they represent around 82.7% of total UK household wealth, which is an increase since I last prepared this calculation.

As I have long argued, I can see no reason why these tax incentives should be provided without conditions being attached to their use.

In the case of private domestic properties, I think that limitations on the scale of the property in question are appropriate, and it is fair to note that some restrictions of this type do not exist, but almost invariably with regard to the amount of land that might be considered appropriate to be associated with a home. It would seem appropriate to question now why properties above a certain size or value also enjoy this relief. What is the point of the state subsidising the already wealthy by letting them enjoy enormously expensive homes, tax-free?

However, this issue is not the focus of my concern in this post. What las long troubled me is the provision of tax relief on savings without conditions being attached.

My first reason for this concern is that although savings might be entirely rational at the microeconomic level of the household, and I am not seeking to challenge that fact, what we now know is that macroeconomically savings perform a very limited function within the economy as a whole. This is because almost all business investment is now funded by borrowing and as a matter of fact, and as the Bank of England acknowledged in 2014, business lending takes place without any requirement for the bank making the loan to hold deposits of funds. New money is created by all bank lending. In that case, there is no relationship between most savings and any form of constructive investment in the real economy now. Very clearly that gives rise to a fair question as to why we might want to spend more than £60 billion a year (about £60 billion for pensions £3 billion approximately for ISAs) subsidising these types of savings.

Second, there is an obvious further problem resulting from the state subsidies. The consequence obvious subsidy is that inequality in the UK is increased. This is obviously true. If the subsidy follows the saving, the vast majority of the subsidy must go to those already wealthy. We are, quite literally, spending a fortune to make the UK more unequal as a result.

Third, it is also troubling that no conditions are placed upon the use that might be made of these tax subsidised funds. They can be saved, in virtually any way the taxpayer desires, without any necessary advantage to UK society arising as a consequence. One perverse outcome of this is the very obvious over-expansion of the activity of the City of London within the UK economy. There has also been the encouragement of short-term investment returns made by companies.

But most of all there has been the dramatic shift away from investment for social purpose towards investment for short-term gain with the consequence that we are seeing throughout society, where social housing, flood defences, low carbon energy, effective public transport systems and other such projects that would deliver social gains have been ignored in favour of share-based saving in particular, where no necessary advantage to society is evidenced

We now face a crisis in the UK. There is no public debt crisis. Nor do we have to pay for Covid, because quantitative easing already settled all the bills for that. But we do have to pay for the transformation of our society so that it is sustainable in the future.

The government is reluctant to use conventional quantitative easing for this purpose because of the boost that it has provided to inequality, and for that reason there are arguments to be made that this type of funding should not be used for this purpose although green quantitative easing, which is quite different in the way in which it works, would remain appropriate.

What we know is that the pressure on taxation also means that funding significant investment out of this source is going to be hard.

In that case, and presuming that the government is reluctant to borrow generically, then by far the largest pool of funding that is available for the climate transition is to be found within the savings accounts of the wealthier UK households.

As Colin Hines and I have long suggested, this requires that conditions be attached to the tax subsidies given to these savings. If all ISAs were required to be saved in bond accounts, with the proceeds being used to fund the Green New Deal, approximately £70 billion a year would be made available for this purpose. If 25% of all new pension contributions were similarly required to be invested for that purpose as a condition of the tax relief granted it is likely that a further £30 billion of funding would be made available each year.

What this latest data on wealth shows is that the impact of the suggestions on the overall allocation of wealth in the UK would be tiny, and wholly affordable. The social consequence would, however, be massive.

The time for the transformation of the UK's saving of its wealth in the interest of funding our green transition has arrived. If we have more than £15 trillion worth of personal wealth in the UK to suggest that we cannot afford to save the planet is quite absurd. Simple changes to the law could deliver massive social gains in this area. When will politicians step up and do them?

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

You are right.

This is a totally absurd situation.

It’s an abuse of the social utility of money.

Unlike ‘account’ based savings however shares and property can go down.

Which might be interesting over the next few months

“There is no public debt crisis. Nor do we have to pay for Covid, because quantitative easing already settled all the bills”

I see someone’s been getting high on the wood polish.

OK

Now tell me what is wring with that

Not BS, but actual explanation

Tell me who we need to repay the debt to

Tell me why we need to repay it

Explain the consequences

As I say, no BS, hard facts

Great point.

Just a quibble about language – it’s not the planet we need to save, it’s humanity and many other species too.

OK….accepted.