This is the third in my audio series on money. It explains how government spending is funded - and how this always involves the creation of new government-backed money. A transcript is to be found below the audio link.

Understanding how the government funds its activities is vital if the role of money in the economy is to also be understood.

Critically, it has to be remembered that government does not function like a household. When it wishes to spend it simply decides to do so. The decision making is embedded in its budget process, which is how it commits itself to a plan of financial action.

Once it has committed to this plan the government does not need to check whether it has financial resources available to enable it so spend. A government that has its own central bank and which is the currency creator for its jurisdiction knows it can always require that the money that is needed for it to spend can be created on demand. It simply makes the promise to pay and the spend can follow on from that: the central bank, which is the Bank of England in the case of the UK, will make payment as instructed knowing that the government's promise to pay can always be fulfilled.

That said, actual expenditure that a government undertakes is incurred through its various Departments. They, like the government as a whole, will commit funds in accordance with their budget. They will then make settlement of the liabilities owing through their clearing bank arrangements. However, the funds expended through these clearing banks will be supplied through the Bank of England.

The Bank of England will provide these funds in the way that every other bank does when advancing money: the Bank of England makes a charge to the loan account it has with the government and provides credit to the clearing bank to which it has been instructed to make payment. This is a completely normal banking arrangement which the Bank of England has confirmed routinely happens.

However, equally routinely, in the United Kingdom at least, the resulting government overdraft with the Bank of England is cleared, at least once a week, and more often if necessary. Excluding very short term arrangements there are four ways to achieve this.

Firstly, tax revenue collected by HM Revenue & Customs can be used to clear some or all of this overdraft.

Secondly, the Treasury can sell bonds to the financial markets and use the proceeds of sale to clear the overdraft.

Thirdly, as was commonplace until 2008, and is now scheduled to happen again from 2020 onwards, the overdraft can be left in place, being described then as the Ways and Means Account. This process is called direct monetary funding (DMF) of government spending by central banks.

Fourthly, and in some ways the most complicated arrangement, is what is called quantitative easing or QE. In this arrangement the government sells bonds, but the Bank of England then creates new funds by making a loan to a company that it owns to buy those bonds back from the financial institutions that have bought them from the government.

There are two consequences. First, UK government debt is reduced - because the repurchased debt is now owned by the Bank of England, which is owned by the government. So this funds the government.

Second, in practice the Bank has, to date, required that some of the cash created by the quantitative easing process be held by the U.K.'s clearing banks with it on what are called central bank reserves accounts. The clearing banks then use these central bank reserve accounts to make settlement with each other when, since 2008 they have not been willing to do so without this arrangement because they do not trust each other to be solvent. This process of central bank reserve accounting gives the Bank of England control over short-term interest rates, which are now largely determined by the rate paid on these accounts.

Add these arrangements together and government spending is funded by a combination of tax, bond issues, money creation through the government overdraft with the Bank of England and quantitative easing. All, however, are reflections of the fact that all government spending injects money into the economy at some point and the process of tax collection, bond sales and (in effect) central bank reserve creation all at some point take it out of circulation again.

Government spending always creates money: the question is how to cancel the inflationary effect of that. And critically, there are now multiple options to achieve that goal. The idea that government spending is funded by taxation is, then, part of history.

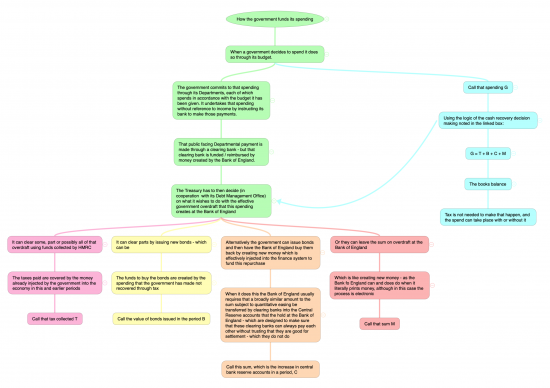

The following diagram may help some explore this issue in another way:

A larger version of this diagram is available here. Alternatively, enlarge your view using Cmd+.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

Very good, as always.

I have minor issues with the paragraph about Clearing Banks’ reserves at the Bank of England.

To be clear, I think the point you are making (that the rate of interest the BoE pays on reserves is the key determinant of market short term interest rates) is absolutely correct.

However, I have a slightly different narrative. I don’t claim that mine is correct… the fog of the Great Financial Crash obscures a lot of what happened before…. and I am not suggesting that you should change your piece….. but here goes.

The introduction of the system of Clearing Banks holding reserves at the BoE predates the Crash by a year or two and was part of the “modernisation” of the BoE’s policy tools. The BoE is “the Bankers’ Bank”; if an account holder at Lloyd’s pays an account holder at Barclay’s £100 then this will be reflected by the BoE moving £100 from Lloyd’s account to Barclay’s account (both at the BoE). You can imagine that there are huge and unpredictable flows so the BoE required Clearing Banks to hold (on average over a certain period) a certain level of money (reserves) in their account. The BoE did not pay interest on these reserves (not 100% sure of this but if they did pay interest it was at a low rate)) so banks aimed to hold the least level of reserves possible and the BoE guided the level of short-term rates by open market operations (mainly Repo). Given a normal growing economy that typically means most open market operations are to prevent rates going too high (versus the policy rate). In short, all the action was at the “ceiling” for rates.

Then came the Great Financial Crash. The Government and BoE did what they had to do to keep the show on the road – massive injection of liquidity to keep the payments system running and bailing out RBS (and others) with liquidity and equity injections.

After this ‘near death’ experience banks became much more cautious. This was reinforced by regulators’ requirements for banks to be more liquid and eventually by Quantitative Easing (which allows the government to spend more without draining cash from the economy…. this cash eventually ends up in the Clearing banks who, with nothing better to do with it, leave it with the Central Bank). In the past the obvious way to deal with all this excess liquidity would be to drain it by repo and the sale of securities…. but hold on, the BoE are BUYING securities via QE! So, rates fall to zero and the BoE loses all control of the level of rates in the economy. Their response was to start paying a interest on those excess reserves that Clearing Banks deposited with the BoE. In short, all the action is at the “floor” for rates and open market operations have been replaced by the rate paid on excess reserves.

Wow! – I had not intended such a long ramble…. but I hope you will agree that we DO end up in the same place but I have taken a slightly different (more “anoraky”) route. Does my story add anything? Probably not…….. but maybe this – that the level of interest rates and the amount of liquidity in the system are two separate policy tools (rather than the ‘old days’ where liquidity levels in the system were used to control rates).

Clive

I agonised over how to say this – and felt it had to be mentioned for completeness and accuracy as it is usually ignored

Your version feels entirely appropriate to me

And I agree this issue is complete and anoraky

I am happy that you think that I do not need to change things – that’s encouraging

Richard

Mr Parry,

Thank you very much for that, I found it an illuminating and informative read. I shall resist the impulse to ask all the questions circulating in my head; but one point only; given what you say, why are the interest rates so high for everyday bank users, when rates are almost negative and we teeter on the edge of deflation? Arranged overdraft rates with the clearing banks are currently around 40%, just for example.

Perhaps you have already answered that with, “…. and the BoE loses all control of the level of rates in the economy”. This is telling. I would be interested to know how you would propose reforming banking.

Could you publish your audio series as a podcast? Would make it easier for people to listen to

If I knew how, I would

I thought Soundcloud was a podcasting platform

What platform do you want it on? Then I will investigate

Thanks very much for continuing this set of explanatons, much appreciated. I’ve been learning about MMT for a while now and though I’m foggy in my understanding about what Clive was talking about (not asking for an explanation here) I think on the whole I ‘get’ MMT.

Just a thought on what happened to the QE, where it went…. from my limited understanding, it looks very much like it went into inflating share prices, so ‘they’ could do it again (e.g. Collateralised Loan Obligations not looking so good at the moment, if I’ve understood correctly).

In addition, I am, though, curious about an aspect of money creation that I’ve not seen (perhaps I’ve not tried hard enough to find) discussed so far, but one thing that seems utterly clear to me, is that of course money has to be created, both by banks in their lending operations, and central banks (hadn’t quite got how complicated that bit was until reading this) via the methods described above. The aspect I’m curious about is that of course money must be created, if only to keep up with what is produced in an economy. e.g. as more goods and services are produced, if there were only ever the same amount of money in circulation, whatever the form it took, be it notes, deposits, bonds etc, then that money would have to stretch further (and it’s difficult to imagine that ‘barter’ was ever real, a la Michael Hudson).

Apologies if this is too embarrassing a rookie question to even post on you blog….

A growing economy requires increasing deficits in other words: the answer to that is yes, unless you want excessive private leverage

This is no catch question but what I fail to understand is why there is a need to purchase bonds by the private sector when the government spends money. Surely it will increase taxes to mop up ‘excessive’ inflation if that occurs so there is no real need for private sector involvement. But surely, more importantly, the purchase itself requires an exchange of funds in the ‘purchase’ of the bonds between the buyer and the government which can only be cost neutral and so there is a match between money in and money out, and so new money is in circulation, or am I being very thick.

Bonds don’t really exist to fund the government: that’s one of the other urban myths of economics

Bonds exist because the government wants to control the interest rate in the economy, and this helps them do so

And bonds also exist because the government wants to provide a service to savers who are seeking a safe place for their funds: in essence, the banking system, as well as the pension and life assurance systems, would have great difficulty in existing without the availability of government bonds

Richard,

Are the variables T, B, C and M as used in you diagram measured and reported in the UK? If so and are available in a historical record, would you point me to it.

No, they’re not reported as far as I know….

But I am working on data now and I may be able to produce that soon

Richard,

I’ve been trying to find on ONS a detailed methodology for their compilation of GDP (similar to US BEA’s 500+ page Handbook) with no success (unless the sole source of their input data is simply surveys). Does such detail not exist or can you or one of your readers point me to it?

Not that I am aware of

But I suspect there is. You just can’t find it

I call the ONS the ONO – the Office for National Opacity

Many thanks for these very excellent useful summaries Richard. If these talks are aimed at the general public, here’s a few suggestions where more clarification might be helpful for Dummies like me.

In talk No 2 you don’t mention the Treasury at all, and here you make a passing reference to it. I think many laypeople don’t understand the difference, or even why there is a Bank of England as well as a Treasury. Treasuries hold the treasure, right? MMT says the government creates money, so why cannot all these transactions , particularly DMF, be done by the Treasury itself?

Why do you call DMF monies an “overdraft” when MMT says this nomenclature is misleading and has value-laden connotations?

Why does the Bank of England have a separate company that buys bonds, what is its name?

In QE, when the BoE buys bonds from the private sector, suppose no one wants to sell at the price they offer? Does the Bank just keep offering a higher price till job done? Or is there legislation that requires the bond holders to sell?

This now sounds like a myth buster question

I vae reposted it myself there

Richard,

I completely agree with your ONO designation. I find nothing there that gives me any confidence in UK GDP (even digging far back into the Archives). In this regard, comparison with the US BEA is night and day. A few years back I came to MMT from BEA publications before even discovering Mosler, Mitchell, Wray, etc.

I very much want to contribute to your TACs program. It’s much needed and I can’t find anything comparable in the US. But most of my arguments come from a GDP view and I need to move them over to MMT phraseology. I’m assuming I can still comment on the TAC page on which you cover an applicable subject and not have to wait for you to bring it up again.

Comment away

Richard,

Went back to post to one of your earlier TACs posts and found that comments are closed. (Only your last two TACs posts are comments-open.) Is that on purpose? It seems that if you’re trying to pull together your best arguments for certain positions or options, comments would be most useful in context with your posts dealing with those positions/options. Otherwise they have to be made to totally unrelated posts that happen to be open (which is ok – just a little awkward.)

I have to close to retain my sanity – I spend a great deal of time moderating

I could not have that many posts open and manage to keep track

It’s hard as it is