The FT reports this morning that:

Britain's tax system is progressive and takes significantly more money from the rich than the poor, the Institute for Fiscal Studies, a respected think-tank, said on Monday in research designed to pre-empt “less than ideal” official statistics suggesting otherwise. The target of the IFS's study was the Office for National Statistics' annual publication on the effect of tax on household income, due to be published on Thursday.

The FT adds:

One of the largest differences between the IFS work and that of the ONS is over value added tax. Officials say it is regressive, with the poor paying a larger share of their income in VAT than the rich. However, the IFS said the ONS was incorrectly classifying people who were temporarily poor, but still spent a lot of money, as permanently poor. It argued that if the effect of indirect taxes, such as VAT, were considered on the basis of how much people spent, rich and poor tended to pay a similar proportion in tax.

I have disputed this issue with the Institute for Fiscal Studies for a long time. I wrote this in 2010, but frankly nothing much has changed in between:

"A new Tax Briefing from Tax Research UK examines that Institute for Fiscal Studies claim and finds it is a statement of political dogma, but not of fact.

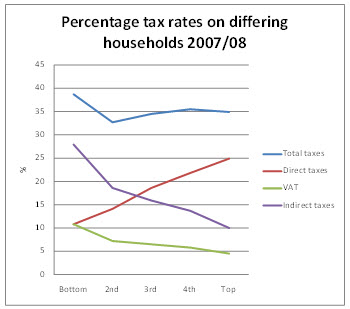

As the Tax Research briefing argues, a regressive tax is almost universally agreed to be one where the proportion of an individual's income expended on that tax falls as they progress up the income scale[i]. VAT is a regressive tax. This is shown, quite dramatically, in the graph below which is based on UK official data[ii] :

By chance the VAT and total direct tax burdens on the bottom 20% of households ranked by their income are the same. Direct taxes then rise steadily as a proportion of income as incomes rise and both VAT and all indirect taxes combined do the exact opposite, falling as a proportion of income as income rises. So marked is the trend that the overall progressive effect of income tax is not enough to counter the fact that the poorest households suffer such a high rate of overall indirect tax that they end up with the highest average tax rates in the economy as a whole.

The message from this data is unambiguous: the poorest 20% of households in the UK have both the highest overall tax burden of any quintile and the highest VAT burden. That VAT burden at 12.1% of their income is more than double that paid by the top quintile, where the VAT burden is 5.9% of income. VAT is, therefore, regressive.

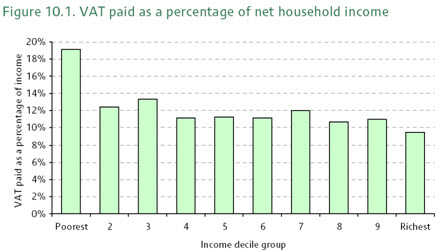

The IFS dispute this. They produce the following data in evidence:

They say of this:

It shows that the percentage of net income paid as VAT varies relatively little across most of the income distribution, with the biggest exception being that the bottom decile group does pay a higher fraction of its net income on VAT than do other income groups.

And they then use this claim to justify the fact that in their opinion VAT paid is not regressive with regard to income.

The slight problem for them is that this overlooks the very obvious fact that it is. Replotting their data and excluding the bottom decile as they would like the following graph can be drawn:

The linear regression shows a clear downward trend that makes very clear VAT is regressive.

Surprisingly the IFS ignore this obvious fact and go on to claim:

However, looking at a snapshot of the patterns of spending, VAT paid and income in the population at any given moment is misleading, because incomes are volatile and spending can be smoothed through borrowing and saving. Consider a student or a retiree: their current income is likely to be quite low but their lifetime earnings could be relatively high. The student may borrow to fund spending, whilst the retiree may be running down savings. Similarly, many people in the lowest income decile will be temporarily not in paid work and able to maintain relatively high spending in the short period they are out of the labour market. Because their spending is higher than their current income, these people will be paying a high fraction of their current income in VAT. Similarly, those with high current incomes tend to have high saving, and so appear to escape the tax, but they will face it when they come to spend the accumulated savings. Because of this ‘consumption smoothing', expenditure is probably a better measure of living standards (and households' perceptions of the level of spending they can sustain).

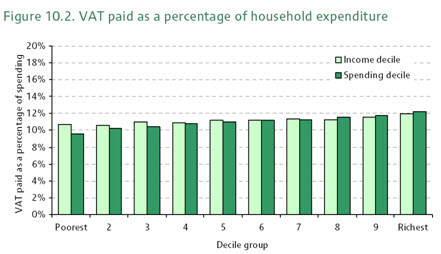

And they then claim that comparing VAT with spending shows that VAT is progressive:

However, this requires that a number of further conditions hold. First, the poor must have savings, and as I show, they don't. Second, they must have access to borrowing, and as I show, they don't (except for doorstep lenders). Third, the consumption patterns of the rich must be the same as the poor, and they're not. In fact, the consumption patterns of the rich (for school frees, private health, leisure travel, second homes and financial services products) are all VAT free, unlike the consumption patterns of the poorest. In addition, the IFS has to abuse all known notions of measure for progressivity to reach this conclusion.

The result is that far from the IFS claim being justified, it is very obviously wrong, and very poor quality research. As a matter of fact VAT is regressive.

The IFS claim is, however, consistent with persistent IFS recommendations that VAT be increased (to replace corporation tax, for example, and on food and children's clothing to pay for “desirable tax reductions”) all of which, together with their recommendations that Inheritance Tax be abolished and tax on interest income be abolished suggest a systematic bias towards making recommendations that favour redistribution of taxes from those who work for a living or who are the poorest in our country towards those with wealth and who enjoy income from capital.

None of which makes it easy to see how the IFS can sustain the claim that [i] it:

maintain a rigorous, scientific approach to research, while offering scope for timely, independent, well-informed contributions to public debate.

The full paper is available here."

And what worries me is that the Institute for Fiscal Studies now says it is to do a five-year study into inequality. I have already publicly stated my concerns about this. But what this continuing claim by the IFS, made on the basis of false claims as to what progressivity is, reveals that they are institutionally unsuited to undertake this work. They have a bias against objective appraisal of poverty. It's not a good basis for undertaking research on the issue.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

An excellent post Richard although it is not good to see the IFS pedalling their half arsed bullshit once again and its a shame you’ve had say this again.

IFS – ‘respected think tank’? By who exactly?

You used to be able to ‘count’ on the IFS to be able to add up the right numbers and come out with a quasi-reasonable result. Now, they are so biased that, while they can still add, so to speak, the results they come up with are so inconsistent with reality that it is worse than a joke. What is going on with this group?

We might like to look at what the bottom and top spent their money on which attracted VAT. The rich might pay a lot of VAT on luxuries like BMW’s while the poor probably spent less on BMW’s and more on everyday necessities.

Some peer reviewing of the IFS might help.

“First, the poor must have savings, and as I show, they don’t. Second, they must have access to borrowing, and as I show, they don’t (except for doorstep lenders). Third, the consumption patterns of the rich must be the same as the poor, and they’re not. In fact, the consumption patterns of the rich (for school frees, private health, leisure travel, second homes and financial services products) are all VAT free, unlike the consumption patterns of the poorest.”

This is a good summation of important matters. It does seem that the IFS wishes to rationalise real poverty into irrelevance; equalisation by extraction. First, the “temporarily poor” do not count as poor. From the perspective of the “temporarily poor” they may not know whether the condition is temporary or not; nor do the IFS. Indeed presumably they may be in work and “temporarily poor”. Second, the permanently poor – captured by lowest decile in Figure 2.1- “the poorest” are then apparently acknowledged by the IFS in these terms: “the bottom decile group does pay a higher fraction of its net income on VAT than do other income groups.” I note how you rebut this using their data; but I do not understand why the IFS appear to think the lowest decile somehow does not count. Our lowest decile in the UK is a dreadful indictment of the gross inequity of our society. I just can’t read past this injustice; because as far as I can see circa 19% is paid by the poorest decile, against 9% for the richest decile (a significant proportion of quite disproportionate incomes): and what would the disparity be between the poorest 1%, who own virtually nothing; and the richest 1%, who own perhaps 24% of the nation’s wealth (Credit Suisse Report November, 2016 reported in The Independent)? The IFS equalisation seems to be achieved simply by permanent extraction of the poorest from consideration. They appear just not to count – even if they are counted.

Are we to suppose this is equitable? All to allow the IFS to score a mere sophist’s point against the ONS? To prove that regressive is progressive. This is uncomplicated sophistry. It is a travesty of fairness. The disparity doesn’t matter? It matters to me.

Have I missed something here? I actually hope I have; because this is gross.

I am not aware you have missed anything

Surely the graph 10.2 showing VAT as a percentage of spending throughout the incomes deciles, which the IFS says, justifies their argument that VAT is not regressive, says nothing of the sort . Those on higher incomes have a greater propensity to save a proportion of their income, whereas those on the lower incomes do not, so spending as a share of income will fall, as incomes rise, and thus the VAT.

Yes

“First, the poor must have savings, and as I show, they don’t. Second, they must have access to borrowing, and as I show, they don’t (except for doorstep lenders).”

So the poor don’t save, or borrow. So their income equals their expenditure. So it doesn’t matter whether you show VAT as a share of expenditure or income, since you’re just dividing by the same number. But the IFS stats show you get a different result if you divide by expenditure or by income.

So something in the above quote has gone wrong.

Yes, your logic that this can be extrapolated across all incomes

Not sure I follow. One of the charts above looks like VAT is 19% of income for the poorest decile. Another looks like it’s 11% of expenditure for the poorest decile.

If the poorest don’t/can’t save or borrow, then income and expenditure are the same, so indirect tax as a percentage of income would be the same as indirect tax as a percentage of expenditure. Since that apparently isn’t the case – not even close – the assumption that the poorest decile can’t/don’t borrow or save must be wrong.

I cannot check out now…but I think you are right about not following

Well, the basic point is simple: if the poor can’t save or borrow, then their income must be the same as their expenditure, so you can take any number you like (eg the VAT they pay) as a percentage of income or as a percentage of expenditure and you’d get the same result. But that doesn’t happen, so income must be different to expenditure for the poor, so they must be able to save or borrow.

One would expect you could interrogate this question directly by just finding out what average income and expenditure in the bottom decile are. That statistic must exist. But after 10 minutes on the ONS website I’m none the wiser. But assuming it’s consistent with the IFS stats, then I think for the bottom decile it must be that expenditure is 1.72 (19%/11%) times that of income. So expenditure is 72% higher than income. So they are borrowing quite a bit!

No, that is what benefits permit

And student grants

And yes there are grants still

Slight correction to my previous comment – if expenditure is 72% larger than income for the poorest decile, then it follows that they are borrowing quite a bit OR using savings quite a bit. In either case the assumption that they can’t/don’t borrow or save must be wrong.

That is benefits and grants

This is known

The IFS are correct with their overall argument but the 2010 report quoted herein makes it poorly. Can I ask why you think they would have a bias against understanding who pays taxes?

“The linear regression shows a clear downward trend that makes very clear VAT is regressive.” This is true, and I don’t know why they claim otherwise. I think probably lazy interpretation of the graph given that the bars there do look somewhat similar but the axis scale is large. The latest publication doesn’t repeat this claim though.

“However, this requires that a number of further conditions hold.” This is just completely untrue though. Do you realise that the figure is based on household survey data covering the incomes and expenditures of a nationally representative sample? Fundamentally, it is the case that income fluctuates much more than expenditure over time, but at any one time (e.g. in one dataset), they will often not be measured as equal – low-income households will often have expenditure above their income and the opposite will be true for high-income households. This is what drives the income regressivity result for VAT and other indirect taxes, but clearly it is not a finding that would be sustained for the same households over time. So, while a strict application of the definition of regressivity to the available data suggests VAT is regressive, the question of the IFS is whether this is a good measure? And the answer is no.

Your assumption has already been addressed and dismissed in other comments

Mr Daniels,

“So, while a strict application of the definition of regressivity to the available data suggests VAT is regressive, the question of the IFS is whether this is a good measure?”

I am not sure what you mean by this statement. VAT is, I think you acknowledge, regressive: period. Or perhaps you mean that, if VAT is regressive that is the wrong answer (at least for the IFS), so measure something else.

The dichotomy I present above is blunt, so allow me to rephrase this conundrum; which the IFS has, after all, seductively invited us to indulge: but in a way that attempts to return us to the underlying issue that is really at stake here: first, precisely what are you proposing is measured, and what is the purpose of the measurement? Second, why is VAT a particularly bad measure, warranting rejection [of whatever you are measuring], other than the fact it can be shown to be regressive?

[…] Source:Â taxresearch.org.uk […]

Why do they want to cut taxes on capital income? Is there some Chamley Judd type reasoning that we’d get higher productivity as a result? I’ve been told that no real working economists believe in the Chamley Judd growth model but these sort of policy stances make me wonder.

I am completely baffled by the logic

I would do the exact opposite

This guy seems to think it makes sense but is he just a nut case or do those ideas have genuine influence in places like the IFS? http://www.econlib.org/archives/2013/03/redistributing.html

I admit I have not got time to read it this pm

Sorry

The supposedly independent IFS is predominantly funded by the ESRC which is predominantly funded by the UK Government which is controlled by the Conservatives. We have a saying in Scotland; “He who pays the piper, calls the tunes.”

You listed in an earlier comment things that .the rich spend money on that are VAT free, but left out things like new cars, furniture, clothing, audio/visual equipment, housing renovations, expensive wines and garden ‘stuff’. All of these carry VAT. It is pure common sense, however your union funded bias interprets this (he who pays the piper indeed) that the rich spend way more on VATable stuff.

It is perfectly possible to be poor and pay next to no VAT. No VAT as a proportion of any income is still zero.

– rent

– foodstuffs

– clothing (charity shops)

– furniture (charity shops/freecycle)

– reading materials (libraries are free)

– public transport

– prescriptions (will be free if poor)

– gambling

– heating (5% VAT)

– vaping (5% VAT for certain products)

If one chooses to drive cars, smoke cigarettes, drink alcohol and buy unhealthy food, more VAT will arise. But these are all choices.

I’ve no doubt whatsoever you will disagree, and condescendingly so. But what I say is just pure common sense.

I do disagree

That is patronising, not evidence-based and assumes those on lower incomes must rely on charity shops

You also get my funding wrong

This is poor politics

What I’d expect from a rural tax adviser really