- The question

The question this note addresses is ‘what's the problem with investing in shares?' By answering that question it also tackles a range of other issues. It has been written in response to a discussion on the Tax Research UK blog, where many commentators said that I was wrong to suggest that investing in shares is now foolhardy and the investing in government bonds or even cash would make more sense. This note explains my reasoning. There is a PDF of it available here.

- The story to date

Investors have usually had five investment options into which to place their funds to date:

- Shares;

- Corporate bonds;

- Government bonds;

- Property;

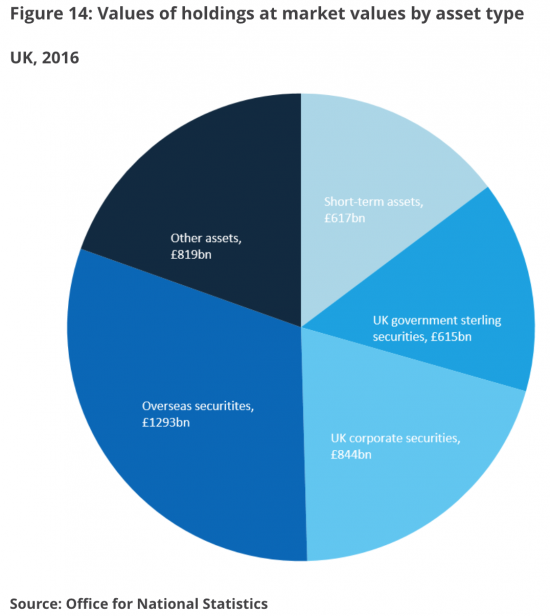

All other options tend to be derivatives of these. The only question most investment managers have faced is what mix of these assets to use. The mix for UK insurance and pension funds in 2016 is shown on the next page[ii]. Short term assets would include cash and term deposits. Other assets include property and hedge fund investments.

What is notable is that these funds rarely actually invest i.e. they do not fund new assets or employment creating activities: they have instead saved, which is a fundamentally different economic activity.

- Returns have been largely risk related

The return on investments is expected to vary:

| Cash | Low or even negative returns in times of inflation |

| Gilts | Averaging more than cash, but because of their security are expected to deliver a low yield. |

| Corporate bonds | Attracting some risk but clearly more secure than shares but less so than gilts, so having a return between the two |

| Shares | Relatively risky investments, giving rise to the hope of returns significantly higher than those available in any bond, whether issued by government or the private sector. |

| Property | The return depends heavily on location. |

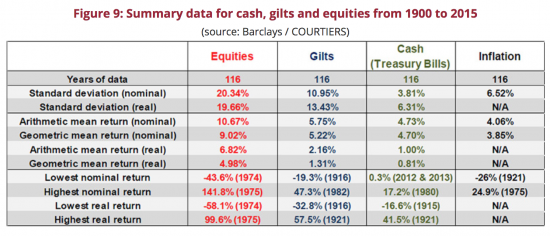

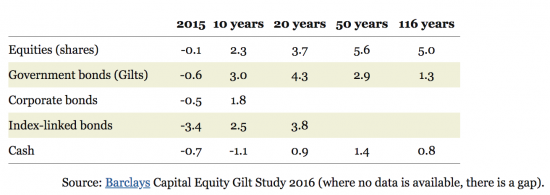

Some data may help. This is long-term data based on information from Barclays Bank[iii]:

Long-term equities appear to win, hands down. Short term the same data source does, however, suggest very different trends[iv]:

The returns are stated after allowing for inflation: gilts have beaten shares over twenty years, but not over 116. Few of us have 116 year planning horizons.

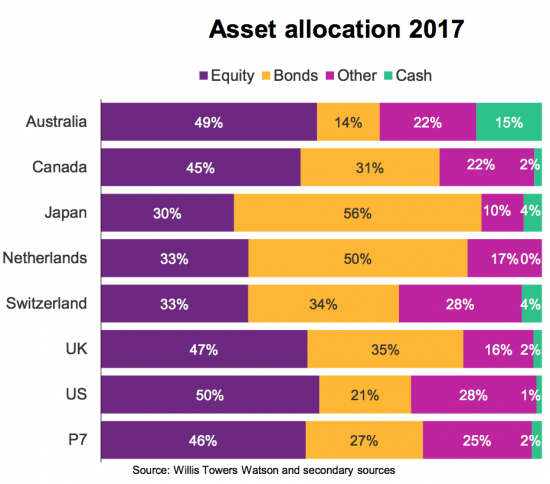

The mix between portfolios in pension funds varies by country[v]:

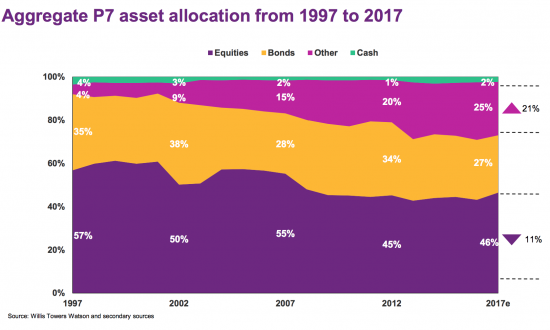

The ratio has also changed over time in the seven countries noted in the previous chart:

Share investment has declined and been replaced by property and other assets (hedge funds, in the main, which manage derivatives of other assets).

- The balance of risks

Managers and maybe individuals invest to balance risks determined by age and risk appetite. The young can take risk, and so their portfolios tend to be biased that way. The older a person gets the more certain they want their returns to be, and they wish to minimise downside potential. They shift to gilts, maybe property and even cash. So portfolios tend to shift depending on the profile of those for whom they are managed.

- Market distortions

I believe it is possible that the conventional logics that have long ordained investment norms may need to be reappraised. There are a number of reasons.

What might be called ‘normal markets' no longer exist. The Global Financial Crisis of 2008 has disrupted what were already abnormal markets. They have not returned to ‘normal'. This is because markets have not acted rationally for a long time and in particular government incentives and taxation have biased returns in many markets in cumulative fashion that may now be deeply significant and potentially unsustainable. I look at each sector in turn.

Property

Property markets have been distorted:

- Subsidies to home owners or landlords to acquire property via interest relief have distorted prices;

- The exemption from capital gains for many householders means that there has been a massive incentive to buy a home, and retain it. The exemption has potentially very significantly increased the rate of return on property investment for many, and had commercial spillover;

- Commercial property markets have also had incentives provided;

- All property markets have been boosted by the constraints on the shortage of supply of land, not just created by planning but by that of very specific location based demand.

Cash

Cash markets have been distorted by the deliberate suppression of interests rates post the GFC: without QE in many major markets rates would not have been low as they have been for a decade. This has reduced the attractiveness of cash holdings in portfolios.

Gilts

The value of gilts has been distorted by QE; that was its intention. The return has been suppressed but as a result their value has been inflated, these having an inverse relationship with each other.

Corporate bonds

The rate of return on corporate gilts has been distorted by central bank measures to suppress interest rates. This was not the intention, maybe, but by increasing demand for these bonds yields have fallen.

Shares

Share valuations have been significantly distorted by a range of policies:

- QE was intended to encourage investment in higher risk assets than gilts: most shares match that criteria. Their value has almost certainly been inflated as a result;

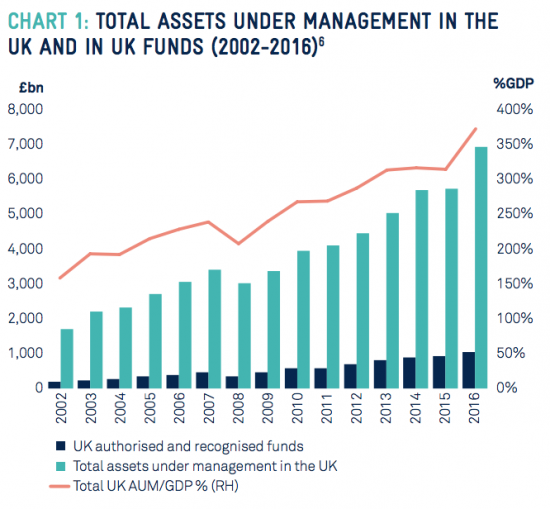

- Pension investment has guaranteed a steady flow of new funds into stock markets over 70 or more years. The increase in the value of investment funds managed in the UK is some indication of this trend[vi]:

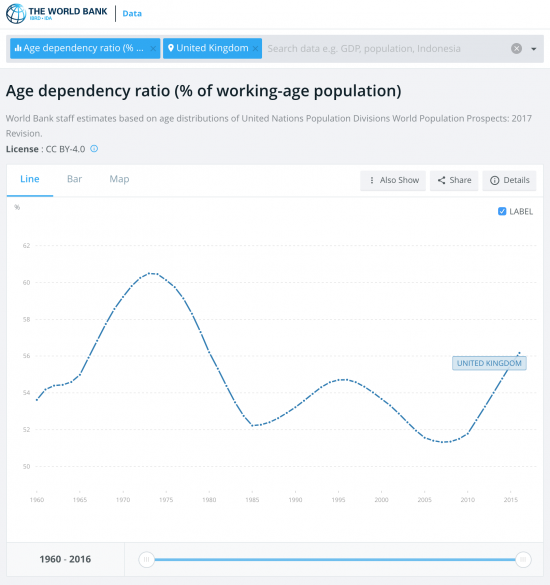

- Inflows to pension funds over this period have exceeded outflows: this is the inevitable consequence of a population that has grown over that period because of rising birth rates, lower mortality amongst the young and net immigration by those who tend to be young at the time of arrival. Dependency rates (the number of elderly supported by people of working age in the population) have been broadly stable for more than twenty years but is now rising[vii]:

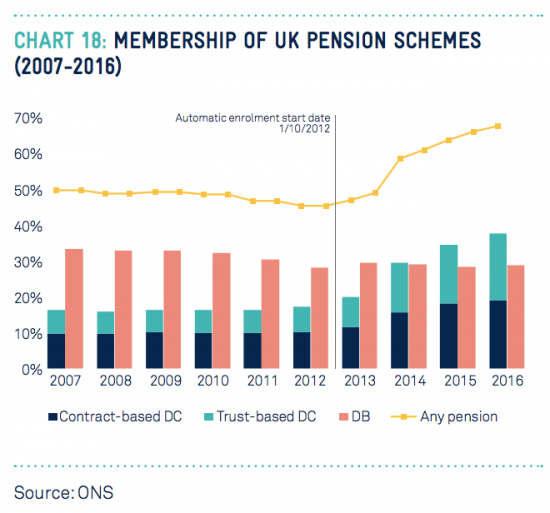

- Pension investment has been encouraged by tax relief or government interventions, either compelling investment now or in the past by incentives matched to the withdrawal of state based options. This has expanded the contributor base in advance of claims made by those of pension age[viii]:

- This has created a net monthly demand for new share-based investments as the portion of the pension contributing population growing fastest has been that with higher risk appetite.

In other words, there has to date been a persistent net, decade-long, buying market for equities as a result. Demand has always been designed to exceed supply. There has as a result been an overall increase in share values over time.

Low rates of tax on non-pension share investment (by capital gains tax) has encouraged this trend.

So too have a wide range of government policies. Amongst these are:

- The rise of The Washington Consensus, intended to (and succeeding at) increasing the overall share of profits in the national and global economy;

- Low, and steadily declining rates of corporation tax to boost the net rate of return on capital;

- Little effective attempt until recently to tackle the use of tax havens that have been used to increase the net after tax rate of return to companies;

- Deliberate moves to shift the tax burden to labour and consumption and away from capital.

All have increased equity share yields.

- The net result

Against this background a number of other trends have emerged:

- Companies have been accumulating funds in excess of their investment requirements. There are varying reports of the size of corporate cash piles: in the US alone the sum is thought to run to trillions and it is a general trend[ix];

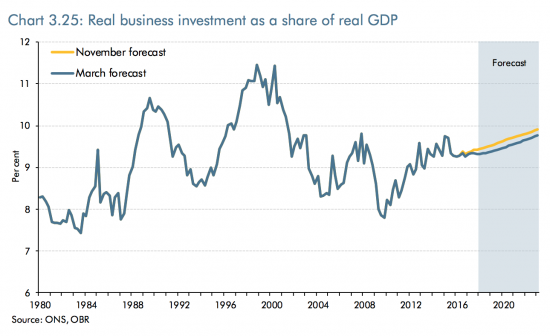

- Corporate investment requirements appear to have fallen: net business investment has been low as a proportion of GDP despite corporate funds being available for investment[x]:

- Companies have used the excess funds to buy their shares back, spending much more on this than they do on dividends now, with a marked correlation to share prices[xi]:

- Buy backs ensure net reducing supply of shares to a net forced buying market, guaranteeing continuing share prices.

- Share incentive schemes and tax incentive schemes have encouraged this behaviour.

- There are almost no new net share issues as a result to actually raise capital: share issues are for M & A (which does not raise new net capital) or buying out existing shareholders, usually on IPO. Spotify floated recently and raised no capital at all.

The consequence has been:

- Wealth inequality has risen, considerably;

- Access to housing has fallen as wealth inequality has risen;

- Inter-generational solidarity has been lost;

- And, bizarrely, pensions are failing because yields on excessive values are so low that increasing life spans cannot be supported by the available return on safe funds used to fund annuities, resulting in increasing pension fund deficits despite massive valuations. The system is not working.

It can also be argued that there has been a failure of the fundamental pension contract i.e. that a retiring generation must leave to the next sufficient physical capital that the next can afford to forego part of its income to sustain that generation now in retirement making use of the tangible capital that they provided to enable them to do so. What has instead been left is financial capital, but that is no substitute for actual assets that generate wealth.

- The real changes in the economy that change all pension (and other investment) assumptions.

There are a number of significant changes in the economy all happening almost simultaneously that should now have a significant impact on investment assumptions:

- Dependency ratios are changing rapidly after being fairly stable for more than 20 years.

- Life expectancy may be stabilising but still foresees very large numbers of the baby boom generation living to ages previously unimaginable for most.

- As the baby boom ‘bulge' really reaches retirement age they will want to swap riskier assets (equities) for safer ones in ever-larger quantities.

- As a result there will now, for the first time, soon be fewer pension fund investors wanting to buy the equities baby boomers wish to sell than there are new retirees wishing to sell.

- This is not just because of demographics, although that is an obvious factor. It's also because of a range of other factors reducing funds to invest such as:

- Stagnant wages;

- Enforced pension enrolment but with very low rates of contribution;

- Increasing student debt repayments impacting an ever growing proportion of the potential investing population;

- Increased housing costs, whether for rent or mortgage payments, as a proportion of income;

- Disenchantment with pension saving as available products cannot provide any assurance of a comfortable old age.

Put all this together and what we need up with is a net equity selling market developing at some time relatively soon for purely structural reasons, irrespective of any actual market condition. And what we know is that markets do not know how to manage down sides: they trend to crash.

It should be noted that there is good technical reason for this which has almost nothing to do with sentiment. Stock markets do not value companies: they value the marginal sale of a share in the company that is available for sale at a point in time. If there are going to be persistently more sellers than buyers in the equities market, as I suggest is likely, then the supply of marginal shares for sale will exceed supply and the result is that prices will fall, and maybe heavily, even if the value of the company as a whole does not. This is a simple function of the way the market works for marginal shares - and cannot be overcome in current market structures.

This, though, is not the only reason why share prices might fall. There are a host of other structural changes coming that will also impact share valuations, These include:

The withdrawal of QE

This is already reversing in the USA. The policy is static in the UK. It is still progressing, but slowly in the EU and Japan. If net reversal happens, even marginally, prices of gilts will fall (as now seems to be desired) and this will ripple, quite rapidly, through corporate bond and equity markets as well. That is exactly what it will be intended to do. And as noted, markets are not with good downsides.

Wealth taxes

There are more likely to be wealth taxes in the future. When even the OECD is discussing the likely reality of such taxes[xii] then it is reasonable to assume that they will happen. At even modest rates current low income yields will encourage net asset realisation to make payment. Another downward pressure will be created.

Financial Transaction Taxes

There is at least a chance that such taxes may be imposed as part of a desire to reduce wealth inequality. The aim would be to reduce asset prices, and they would almost certainly succeed in doing so.

Tackling tax abuse

The OECD is finally implementing its Base Erosion and Profits Shifting programme, and country-by-country reporting in particular. Many corporations are suggesting that effective tax rates may increase as a result, and it will certainly be true that tax haven usage will be harder, at least with the tax savings seen in the past. This will reduce net profits after tax and reduce corporate valuations, and so share prices.

Automation

Automation is coming: that is a reality. This need not create economic problems if the right reactions are put in place in the economy as a whole, but at present there are no signs of that and if, as planned, companies massively automate very rapidly in economies where there is no alternative government backed policy to create alternative employment the net outcome will be the ultimate example of a fallacy of composition: because it makes sense for one company to automate in isolation cannot mean it does for all to simultaneously to do without compensating policies being in place. The net outcome could, all too easily, be a crash in consumer demand as too rapid a change in employment practice creates a crisis for consumer incomes, and so spending, with consequent massive on costs for companies that see demand for their products fall despite any savings they can pass on from automation.

Peak oil

The reality of oil company valuation is going to hit markets. Oil companies are valued as much on the reserves they claim to have access to as they are on current revenues they make (and which might be projected into the future). Companies argue that they can and will access all their existing reserves and constantly need to find new ones: the fact is that oil and climate experts strongly disagree and suggest instead that large parts of current known oil reserves will have to stay in the ground if we are to have any chance of not frying the planet in the future. This is going to be realised at some point, with consequent knock on effects for other extractive industries. These industries make up a large portion (maybe a third) of the value of many mainstream stock indices at present and the consequence of this will be significant falls in value.

Bank overvaluation

Banks and other financial institutions also have over-valued shares. They have gained enormously from conventional QE. As asset traders they have all gained enormously from artificially inflated asset prices that have benefited a selected few in society (the wealth owners who are their clients) at the cost of increasing wealth inequality. Any unwinding of QE will have impact on the valuation of these assets that has yet to be reflected in bank and financial institution market prices, with significant impact on overall portfolio valuations due to the importance of such companies in most stock exchanges.

The next downturn

Historically we tend to have downturns in the economy every seven to eight years: markets have not really downturned now since 2008. We are overdue for a market adjustment on the balance of probabilities although it cannot be predicted what, precisely, will trigger that event. There are plenty of current situations, from trade war to Brexit to international tensions that might, however, do so.

- Put all these facts together

Put together I believe that these scenarios create a pension tipping point because of:

- the end of QE over-valuation with all its knock on effects;

- the ill thought through consequences of automation;

- oil usage changing, and

- tax and related policy changes.

All are likely to happen. The result is that we face having an extraordinary range of issues arising simultaneously that suggest a substantial change in stock market valuation in a downward direction that is now overdue.

And, of course it may not happen: no one can ever be quite sure about these things and the proverbial ‘black swan' that could sweep values to new heights may be just around the corner. But companies themselves do not seem to believe that: their whole strategy of share buy backs to reduce the absolute supply of shares and their reluctance to now use equity issues as a form of finance suggest that they too are all too willing participants in a con-trick on the clients of institutional investment houses from which the various forms of finance can still all be winners, but few else will be.

- What might happen?

This is the obvious question to ask. There is no obvious answer. All that can be said is that there will be a trigger event. It may in itself appear inconsequential, but when the appreciation of overvaluation arrives it is likely that the realisation will deliver a downturn more serious than any previous post war downturn. This is likely to be 1929 all over again, with the crash not just indicating the end of a bubble (which we have clearly had) but something much more fundamental. It will indicate an end of an economic era. That suggests that no minor transition and no minor bail out (such as QE) will solve this crisis: this time only radical reform will solve the problem.

- The end of neo-Keynesianism and the rise of new fiscalism

In the 1930s this was The New Deal. Eventually, of course, it was Keynesianism. But much as Keynes still has value too much of what is called Keynesianism has been tarnished by the neo-Keynesian school of thought that has been far too close to neoliberalism for comfort.

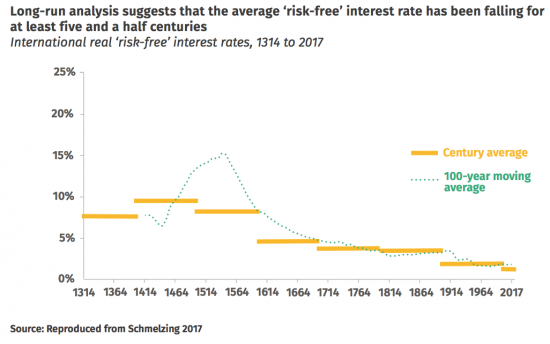

And Keynes did not, in any event, foresee the end of the gold standard worldwide; the universal supply of cost free money created by sovereign currency issuing governments and the end of the shortage of supply of money as a consequence. This new money supply has meant the effective near elimination of official interest rates as governments can no longer charge for what they can create for free, and at will. In other words, what Keynes could not have foreseen was the ending of interest rate policy as a mechanism for controlling the economy, although that is what has actually happened.

This fact is at the very core of the crisis we now face. We have an economy, and systems of economic management, plus policy for managing pensions, that are all built on the idea that because money is scarce interest must be paid for its use. But that is no longer true: money is not scarce. And its price, at least to government, reflects that fact:

As the official price of money has fallen, so too have asset prices inflated. But that's because money is still seeking what is, in effect, a risk free (or nearly risk-free) interest rate return when there is almost none to be had. This is true even in the case of equity investments: the number of these that actually fail is tiny.

The new economy has to be built on the basis that there is going to be little interest return.

First that means that monetary policy is, and will remain redundant as a tool for macroeconomic policy management. The focus will now be on fiscalism; that is the use of spending and tax to manage the economy. There will be no choice: these will be the only tools we have.

More importantly, this demands a whole change in the way we invest in a way that has not happened in current lifetimes. The focus will now be on investment to meet need.

Some of that need will be met by companies but the focus will be on product creation to meet need, not to leverage returns.

And some of that need will be met by government, and that will make them, through a National Investment Bank, a major focus for future saving in a more formal sense than has been the case in the past.

This is, of course, what the Green New Deal[xiii] has now been saying for a decade. But that's the subject of another paper.

- Endnotes

[i] Professor of Practice in International Political Economy at City, University of London and Director, Tax Research LLP. Contact details available at http://www.taxresearch.org.uk/Blog/about/

[ii] https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/investmentspensionsandtrusts/bulletins/mq5investmentbyinsurancecompaniespensionfundsandtrusts/octobertodecember2017

[iii] http://www.courtiers.co.uk/news/barclays-equity-gilt-study-2016

[iv] http://monevator.com/uk-historical-asset-class-returns/

[v] https://www.willistowerswatson.com/-/media/WTW/Images/Press/2018/01/Global-Pension-Asset-Study-2018-Japan.pdf

[vi] https://www.theinvestmentassociation.org/assets/files/research/2017/20170914-ams2017.pdf

[vii] https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.DPND?locations=GB

[viii] https://www.theinvestmentassociation.org/assets/files/research/2017/20170914-ams2017.pdf

[ix] https://www.ft.com/content/b2df748e-8a3f-11e5-90de-f44762bf9896?ftcamp=crm/email/20151117/nbe/InTodaysFT/product

[x] http://cdn.obr.uk/EFO-MaRch_2018.pdf

[xi] https://www.ft.com/content/e7fb2144-fbae-11e7-a492-2c9be7f3120a

[xii] http://www.oecd.org/publications/the-role-and-design-of-net-wealth-taxes-in-the-oecd-9789264290303-en.htm

[xiii] https://www.greennewdealgroup.org/

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

I will have to read that again……..

…….. to see if I can find anything even slightly contentious.

Good luck

Essays like that are what Bank holidays are for…

A very fine analysis.

I will only comment on a sector that I know well and into which I invest – renewables (RES). To a great extent governments still control the flow of projects (for any RES tech). The slowing down of REs projcts in Europe has led to some companies (such as Vestas) doing share buy backs – since there is simply not enough business out there to justify company expansion. Companies such as Siemens, Vestas and Orstead (RES developer) have globalised their activities – which in some ways mitigates local impacts. In the case of oil companies – they have yeilds twice those of RES companies. Some such as Shell are attempting to move into RES – possibily too little too late & in any case – RES is low yeild territory.

In terms of RES and in terms of need, I see no alternative to a Green New Deal (at least with respect to the UK) – it is the only approach that will moblise the monetary resources needed to de-carbonise the economy.

Thanks

A new Green New Deal report is on its way

Wow. The inevitability of gradualness. I wonder if anybody in the Labour Party will read it. I hope so because I’m sure no one in the Conservative Party will.

The elephant in the room is that these analyses do not discuss the balance of power between capital and labour.

This isn’t just a statement of the obvious, that rising asset prices can and do represent labour receiving a decreasing share of the value added in the economy; it is also a warning that this decreasing share runs alongside a diminished role in politics…

….Which does not bode well for a ‘fiscalist’ approach to macroeconomic policy. Bluntly, a government with no purpose beyond maximising the concentration of wealth and minimising the economic participation of the poor isn’t going to ‘do the right thing’.

It will do the opposite, and seek to maintain the value of its owners’ portfolios, even when all economic logic would say otherwise; even, and long after, it becomes untenable and unsustainable.

The alternative is?

The alternative is to break out of the straitjacket that politics is in: we do not have to be ruled by whoever marshals enough money to manipulate the media and buy the election.

The advance indicator of that happening would be real public anger at funding irregularities in election campaigns and referendums; likewise, at bad media coverage; and, overall, much more engagement in politics – even negatively, as anger – rather than the resigned indifference we have today.

The good news is that I see this happening among my French colleagues and practice partners, and I suspect that this is true elsewhere in Europe: Britain has done sterling service, as a warning to others.

We can hope

Nile says:

“The elephant in the room is ……..the balance of power between capital and labour.”

and

“Bluntly, a government with no purpose beyond maximising the concentration of wealth and minimising the economic participation of the poor isn’t going to ‘do the right thing’.”

I think that just about lays out the battle ground, Nile. It sounds depressingly familiar.

If the GFC was not a sufficient shock to the system to encourage a change of political direction, one has to wonder what it will take.

I try not to think in terms of a ‘battle ground’: we have now reached a stage where economic policy and economic warfare are one and the same, and no-one in power knows or cares that this is a less-than-zero-sum game with no ‘winner’.

Further, we have already reached a stage where all the major players regard democracy with contempt: at worst, a contest of media ‘spend’ or media ownership, where there are no consequences for lying and limitless resources for smears and distortion of the truth…

…And, on what I suppose to be the ‘other side’, a broad agreement to concede the neoliberal argument that the ‘victory’ of economic warfare is inevitable, unquestionable, permanent, and right; and, worse, an eagerness to participate in the worst of the lies, the coded speeches about ‘controlling immigration’ in the hope that we, too, can gain our rightful share of all the votes that we can get from being ever such a little bit racist.

And, in all of it, utter contempt for economics and the lives of ordinary people.

In such circumstances, the first priority is de-escalation and deconfliction: getting out of the trap of exploiting division for gain, and back into discourse, the dissemination of accurate and verifiable information instead of mere propaganda; and, above all, moving a disengaged and disinterested population back into a world of effective Parliamentary democracy.

The alternative is that the disengagement becomes alienation, and a decisive shift into the other sort of extra-parliamentary politics: and this is already closer than it should be, because significant factions of the right – ‘Hard Brexit’ fundamentalists, and organised neo-nazis – are economically indististinguishable from nihilists and exercising real political power.

So: I have to shift away from ‘battle ground’ framing and the powerful rhetoric of conflict that I can use very effectively – and I am far, far too good at that – and move everyone I speak to back towards consensus-building and re-engagement; and so should you.

I’m sure (ish) that you are right about all that, Nile.

[…] suggested the issue is somewhat bigger than that, […]

[…] that quite a lot of readers did not get to section 10 of my blog on why shares are overvalued, published yesterday. It did, however, include the most important arguments in the whole post, touching on issues that […]

That trainee analyst’s research based on the Barclays data is interesting, particularly the conclusion that “When looking at rolling annualized returns over longer periods, the volatility of real equity returns starts to decline, and after eleven years it is lower than the volatility of gilt returns.”

Of course, past performance is no guarantee of future results.