I was asked yesterday if I would write about pensions as part of the series of blogs I have done over the last few weeks on pretty fundamental economic issues. I'd have liked to do something new, but work (and holiday) has got in the way and so I offer something that's two years old, but which I would only have updated a little at most. I hope this does the job:

The need to save is innate to many humans (not all, I know: some always assume tomorrow will sort itself out). The reasons for saving vary from simple caution about the proverbial rainy day, to family provision (education, weddings, housing), to retirement. I suspect the variety of motives is remarkably small the world over and these three explain most savings. In most cases there is also likely to be strong risk aversion on the part of the saver: those who save are, almost by definition, cautious people.

What the world offers them are essentially three products. The first is cash and its close relations, including gilts (although these have downside risk, especially with present interest rates) and (maybe) corporate bonds. The latter tend to merge risk into the next category for saving, which us broadly based around shares. Beyond these there is the illiquid market. That's made up of your own business (yes, that can be a savings mechanism if the aim is to realise a lump sum) and property. Go much further into categorisation and you come into a derivative of any of these.

The difficulty in all this is multifold. First, cash saving is essentially a negative act. In times of low inflation it is a safe act and, with deposit guarantees, broadly secure but it yields next to nothing and, as importantly, does nothing for the economy. Saving in cash effectively takes money out of active use. It is a loan to a bank that then forms part of its capital (it no longer remains your money: it does belong to the bank once deposited and all you own is a loan recorded in a bank statement) but what we now know is that banks do not then lend this money on: all the loans they create are made out of new money created for the purpose. They do not therefore, effectively, need deposits to make loans. Unsurprisingly, as this realisation has dawned so too have cash deposit rates fallen, in real terms, to near enough nothing to reflect their near worthless economic status.

Gilts are a surprisingly hard to access savings mechanism for the average person: National Savings is the alternative product for many. What's the plus? The person you're lending the money to is guaranteed to repay. Plus, they use the money for social purposes and there is no intermediary: the government sells the product and it uses the money. It's a surprisingly rational savings mechanism, but one with a dull reputation unless the rates are out of line with expectation.

Then there's the stock market. In this case we go out of our way to incentivise this arrangement. Once almost all mortgage savings were in it. Now a significant (but falling) part of pension savings are. And ISAs are still used to encourage it. The incentive is even encouraged by subliminal messaging: on the hour almost every hour the news tells you what is happening on the markets and most of the time that induces feelings of good news: markets rise steadily and do down sides rapidly. It's as if there is a conspiracy to lure money in.

But why are we promoting stock market saving, which it is what it is unless the shares are newly issued, which the vast majority are not? This stock market trading is almost entirely about redundant money: almost as useless as cash in its economic impact. When you buy a share it is almost invariably a second hand piece of paper you are acquiring: someone else other than the company whose name is on the share certificate sold a property right in that company to you and (although many people seem to think otherwise) the company that created the share that has been sold gains or loses not a penny in the process. In the case of many companies it is also many years since they created any new shares: the stock market in shares is now rarely used as a mechanism for raising money for investment, which is a process undertaken almost entirely through corporate bonds, which few smaller investors have any knowledge of, and which are almost entirely institutionally owned. So, the truth is that the stock market, and saving in it, does not produce new investment funds. It is almost as hopeless in this regard as saving in cash.

No investment conspiracy is needed to get money into property. For those who can access the market the appeal is obvious: it is in short supply, there is a real demand for it and, just as importantly (if not more so), it's utterly comprehensible. Do not fail to notice this last point: ask most people to explain the economic realities of any of the other savings mechanisms and I expect they may well have real difficulties, even with the reality of cash deposits. Property also has an obvious use as a long term savings mechanism, even if the very process of using it as such means many who want to own property are denied the chance to do so: that's the paradox in this savings market; using it for saving frequently undermines the goal of providing secure housing.

Small business saving does, I think, fall into a wholly different category. I am going to ignore it.

But having made these points let me be clear. What they reveal are three things. The first is the difficulty people have with understanding savings. Very few people have any real understanding of the mechanisms that they use to save or what the impact of those mechanisms on the real economy is. This leads to serious errors of judgement, mismatched expectation and to exposure to mis-selling, loss and even fraud.

Second, most ‘saving' is unrelated to any investment activity, meaning that little economic gain arises from it.

Third, saving in these largely economically useless ways allocates vast amounts of energy to supporting this activity when in many cases little or no return is actually generated as a result of that activity.

Last, and perhaps most significant, given that the most important reason for saving is, without doubt, to provide for old age, the fact that many of these savings mechanisms cannot actually generate the returns needed to support people in their old age means that in large part they are unsuited for that purpose. There is massive market failure as a result.

I explained the essence of this in a short publication I wrote in 2010 called ‘Making Pensions Work‘. A lot of what I wrote then does, I think, remain completely relevant today. At the heart of my concern was the failure of what I called the ‘fundamental pension contract‘:

This is that one generation, the older one, will through its own efforts create capital assets and infrastructure in both the state and private sectors which the following younger generation can use in the course of their work. In exchange for their subsequent use of these assets for their own benefit that succeeding younger generation will, in effect, meet the income needs of the older generation when they are in retirement. Unless this fundamental contract that underpins all pensions is honoured any pension system will fail.

As I then argued of private pensions:

This contract is ignored in the existing pension system that does not even recognise that it exists. Our state subsidised saving for pensions makes no link between that activity and the necessary investment in new capital goods, infrastructure, job creation and skills that we need as a country. As a result state subsidy is being given with no return to the state appearing to arise as a consequence, precisely because this is a subsidy for saving which does not generate any new wealth. This is the fundamental economic problem and malaise in our current pension arrangement.

If anything matters are now worse than I envisaged at the time. George Osborne's pension reforms are turning what was meant to be a pension system into a tax subsidised short-term savings arrangement for those already well off: it is staggering that, as the FT has reported this week, two-thirds of customers surveyed by Royal London, the largest mutual life, pension and investment company in the UK, took their entire pension pot as a cash lump sum following the introduction of the pension freedoms in April. Most seem to have no intention of using those funds for pension purposes now, and George Osborne is simply exploiting this financial short termism for the purposes of securing his own short term tax hit.

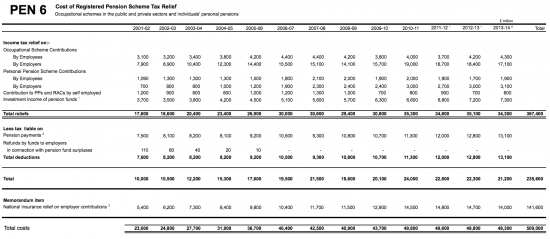

In the face of this effective collapse of the private pension system some radical re-thinking of pensions is needed. This is no small issue either. As this table, adapted from that published by HMRC, shows, the cost of pension tax relief over the last 13 years for which records are published is £509 billion (click for a larger version) :

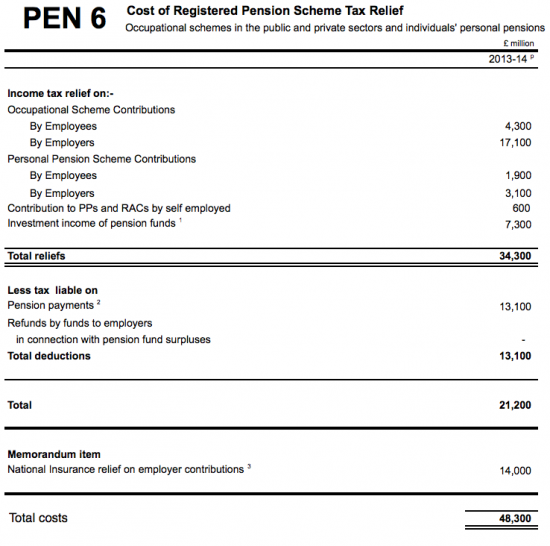

For the sake of clarity the data for 2013/14 alone was:

Now, I accept that if totals are considered some offset of tax collected is appropriate, (although of course much of the tax collected would have related to contributions from before this period, so the direct offset of tax against cost is not appropriate), but however looked at the cost of these reliefs in proportion to total government spending is enormous. In 2013/14 total government spending was £720 billion. And let me be clear, the taxes on past pensions would have been received in that year in almost exactly the same amount if no new tax relief had been given. So, the net effect was that a subsidy of £48.3 billion was given to the pension sector, equivalent to 6.7% of all public spending. To put this on context, defence spending in the year was £40 billion, housing and environment spending was £21 billion and public order and safety cost £31 billion.

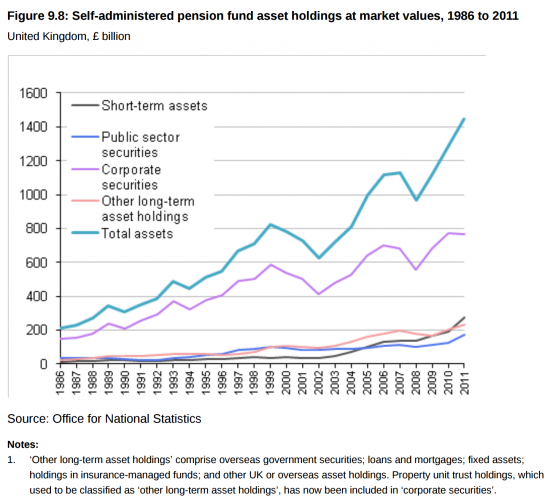

The latest reliable data I can find on allocation of these sums comes from the ONS in Pension Trends — Chapter 9: Pension Scheme Funding and Investment, 2013 Edition. There the mix of assets invested in the largest category of pension funds is shown to be as follows:

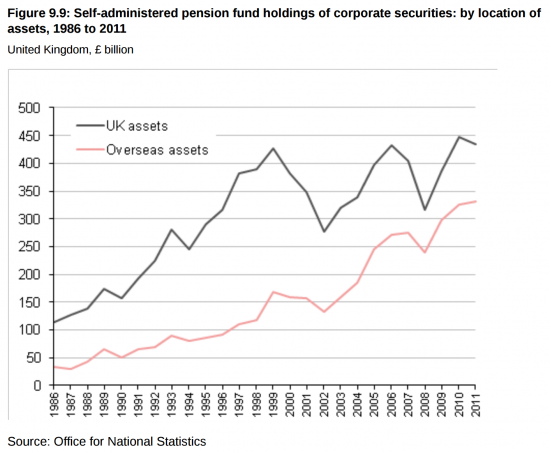

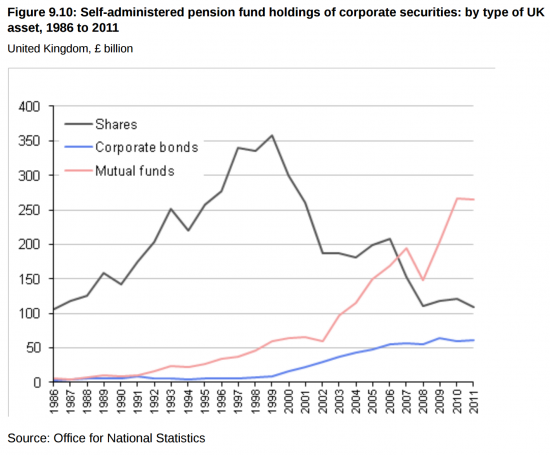

There was a flattening in corporate exposure post 2009, and this figure includes bonds and equity with overseas holdings growing significantly over time:

This is a trend seemingly associated with a growing use of mutual fund investment:

Now I stress that I know that this is not the whole picture on pension fund investment, but what seems to be fairly obvious is that the trends that are occurring are broadly towards increasing financialisation, less direct engagement with UK corporates and an increasing international diversification to the point that the obvious question has to be asked, which is what is in this for the UK government and what now justifies its massive spending on pension subsidies?

To put it another way, why are we willing to spend £48 billion a year subsidising the financial services sector in the UK and abroad when doing so is not resulting in funds being used to, in almost any way, fulfil that fundamental pension contract that I outline above?

And why, at the same time, are we tolerating the use of those funds to a) support the increasing financialisation of our society b) support activity largely based in the south east of England c) increase wealth divides in society, which is what this process, inevitably, does?

I can no longer find reasonable answers to those questions. I stress, I am not alone in doing so: George Osborne is floating the idea of an ISA based pension with substantially less tax relief given. There does, however, remain a problem with that: the fundamental pension contract that requires we pass on real assets — houses, infrastructure, functioning businesses, knowledge, intellectual knowledge and the mechanisms that support all these things — is likely to be even more ignored in a personal ISA based pension than it is at present. What we will actually have instead us a continuing savings deception largely, it seems, designed to ensure that the financial services sector got rich in real time.

It was for this reason that I suggested People's Pensions along with Colin Hines and Alan Simpson (then an MP) in 2003. The idea was simple. The government would create a pension fund, or funds, in which people could invest. This fund would then fund the creation of the assets that the nation needs to ensure that the fundamental pension contract was fulfilled. So it would finance the building of hospitals, schools, broadband for rural locations, insulated properties and invest in small business and high tech and so much more. The fund would attract tax reliefs: an ISA wrapper may work for investments in it. Alternatively, capital gains and income received from it, to a limit, could be considered tax free. And the fund would then work in partnership with (let's call it) a National Investment Bank, whose bonds it would buy and who would actually deliver the projects. The same National Investment Bank would also issue those bonds into the broader market for those who wanted to buy them: they would also be available for the purposes of People's Quantitative Easing when the government, via the Bank of England, believed it needed to stimulate the economy by increasing investment in these assets.

How would returns be paid? Three ways. First, by way of interest payment: that's hardly surprising. The government is used to paying interest on its borrowing.

Second, there would be a real current return on the investment: I think it would be entirely appropriate to designate local funds or sector funds so people could see that the money they were investing was linked to a real economic output. Nothing could make investment more comprehensible than that.

Third, there is, of course, in the long term a return to be paid as a state backed pension based on contributions. The mechanisms would need refinement, but given that government bonds have for decades underpinned the annuities used by private pension funds such an arrangement is completely normal. The important point to make though is that this pension could be economically justified precisely because the assets underpinning it would still be in use: this is a pension contract that reflects the inter-generational agreement that must underpin such arrangements with real assets.

How much could be spent a year on new investments? Well, let's start with most of that £48 billion, shall we?

The gains are obvious. First the fundamental pension contract would be recognised and be the basis for pension provision, for maybe the first time ever.

Second, the savings mechanism would be readily comprehensible, have low risk and be secure.

Third, a mechanism for increasing the flow of funds into the productive economy and away from the financial services sector — an essential part of rebalancing the economy — would have been created.

What's not to like? Ask the City. But for the rest of us this is all gain.

First this is a programme to deliver real investment.

Second, it redirects pension subsidy to public gain.

Third, it rebalances the economy.

Fourth it creates jobs in every constituency in the UK.

Fifth it creates an understandable savings mechanism.

Sixth, that mechanism reflects the fundamental pension contract that must exist in the macro economy.

Seventh, this provides a mechanism for enduring people's quantitative easing when it is needed.

Eighth, this is clear economic narrative that is straightforward to explain both as to the reason for its creation and as to its long term benefit.

And it's open to any political party to use.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

Outstanding.

Thank you.

But also saddened by the fact that the right people need to take this on board too.

Interesting and although many might say it does read like a two year old’s piece of work it is just as important as when you first wrote it.

Leading on from your other idea that saving was just a negative act and just takes money out of use then we should be discouraging saving for pensions and as we can print all the money we need then perhaps reward people for spending not saving by giving them pension credit the more they spend which will be all win win.

Well done Richard for saying things other economists haven’t even thought of.

I am baffled: if you know a two year old who could write that I will be amazed

Alas, Richard, yet ANOTHER example of “the curse of the apostrophe”!!

There’s a club near me, that has a sign proudly boasting its ability to offer a venue for “wedding’s, party’s and birthday’s”, or some such weird collocation of wrongly apostrophised “get-together’s” (as they would term them!!)

I also regularly see “locally grown strawberry’s” on sale, and puzzle is to which part of a strawberry, locally grown or otherwise, is, or indeed, could be, on sale. Strawberry leaves, as are sported on ducal coronets? Alas, I think His Grace the Duke of Omnium and Gatherum would want the real thing, made out of precious metal!

Clearly, as you will certainly have known it SHOULD have read “a two-year old” article, rather than “a two-year old’s article”, which would indeed have surpassed the alleged achievements of Macaulay, who is said to have mastered Ancient Greek by the age of 4!!

And now I feel a bit stupid!

“many might say it does read like a two year old’s piece of work”

I did think that sounded a bit harsh!!

As they say, “Good punctuation is the the difference between knowing your shit, and knowing you’re shit!”

We’ve all done it1

Brilliant Richard, thank you. Just out of interest, are there any other countries that follow this model?

None

Sorry to disappoint

A further advantage of bonds for ‘future’ infrastructure is that it gets rid of the stop go of direct government dictat. Once you have the bonds issued and purchased there is effectively no going back. And if the bonds aren’t issued yet, well it’s obviously a wish rather than firm intent. This greater certainty and stability would be of great benefit to UK construction companies and engineers.

(The recent cancelling of much railway electrication would be a good example of how uncertainty is currently inbuilt.)

I like that idea…

And I bet right now there are a lot of people who would buy Welsh Electrification Bonds

Thanks – an interesting idea the People’s Pensions. We certainly need to reform the way governments have turned private pensions into freebie for the wealthy. “X has just left his/her job with Y to join Z at a base salary of £1.5m plus pension, bonus and incentives.” And worth every penny. But as the millionaires Morecambe and Wise used to say “What about the workers?”

And in today’s FT there were several items about pensions: worries about “Cashing In”; need to save >18% of salary and the State Pension slipping away into the future, if indeed it survives.

Apparently we can’t afford the state pension, and have to increase the pensionable age and “encourage” people to work longer and longer. There’s even talk of Means Testing. Yet it seems we have one of the stingiest state pensions in Europe.

Is this just Neoliberalism again? In an item I found in the online Torygraph from a couple of years ago, John Macnicol (a visiting Prof at the LSE) certainly thought so.

If we follow your argument from your previous article then we can afford a decent State Pension if we have the political will and if politicians ceased worshipping at the alter of neoliberalism and understood economics.

We could

We require the political will

Postponing the age of eligibility for the state pension at the same time as floating the idea of a Citizens’ Income strikes me as truly oxymoronic (or maybe simply moronic) thinking.

Except, of course, those who seek to postpone the payment of the State Pension till the would-be recipients are either 80, or preferably pushing up daisies, are not the people as those arguing for a Citizens’ Income.

But if a UBI or Citizens’ Income ever is established, the argument for postponing the payment of a State Pension will simply fall by the wayside, and the only argument will be whether the UBI is larger or smaller than the State Pension.

I know this will be unpopu;ar but…

If you keep bullying people ino healthy lifestyles, you will eventually realise that healthy lifestyles are unaffordable.

The only reason the pension worked was that working class men spent their entire lives working, smoking 40 a day, retired & dropped dead.

[…] finance infrastructure projects, linking the idea to the Green New Deal, pension investment and the fundamental pension contract about which I wrote […]

Very good points

I particularly like the observations about the stock market and the city

Often regarded as an important wealth generator I never have quite understood.

I can see that the city pays a lot of tax on the profits of city firms and income tax on its highly paid employees

But wealth creators?

How can this be?

For as you say it is only new issues of shares that serve the classic function of fund raising for a business. The rest and surely the majority is in providing a market for second hand or ready issued shares. Here for every winner there is a loser, no extra capital is raised and the only wealth created is the commissions earnt by the city firms acting as agents.

How do you see cash savings deposited with a building society rather a bank that does not raise funds on the money market – unlike the old Nothern Rock?

Surely you would accept that these deposits do serve a purpose? That they are in fact lent out in the firm of mortgages?

I do hope as I like to think that I have done my bit, having stayed with my cash savings in these building societies since 2008. I like to think that my savings have been used constructively and lent out as mortgages. My low interest rates making it easier for those struggling with mortgage payments.

Or am I wrong?

Regarding pensions I like your ideas for a people’s pension.

As you know the government are again encouraging people to make pension contributions with auto enrolment, etc.

This is surely history repeating itself?

I recall meeting clients some 30 years ago to do their annual accounts. They would say, by the way Gareth, I saw a nice man from Allied Dimdoor the other day and he signed me up for a £50 per month self employed pension contribution. He told me that when I retire it will pay me a very nice annuity and a tax free lump sum to boot and that I need not really worry too much about the state pension as compared to my annuity it won’t be worth very much. He also said that his firm would provide me with advice throughout including advice when I came to take the annuity and lump sum.

Shortly before my retirement I met several of these clients that I had dealt with for all those years to do their final accounts. They passed some paperwork from the pension company showing what all their £50’s had amounted too.

Let’s just say it fell well short of their expectations – the projected annuity was but a fraction of the state pension.

I explained that I was not a financial adviser and he should consult one. He was reluctant to do this as he would have to pay an hourly rate.

The point I am making is that the government (all to a man on generous state funded pensions and many still defined benefit type schemes) encourage the rest of us in to pensions. But these will be defined contribution schemes. The contributor bears all the risk for the performance but is probably not qualified to choose the right areas in to which to invest his contributions. He could use a financial adviser but I would be interested to see historical data as to how good they are. From my own experience I rate them poorly.

And where are the rates of return on pension contributions to be made. I keep reading articles in the economist, etc that the previously expected rates of 6 to 8% are far too optimistic and realistic rates are sub 5%

I am not surprised that most of the people with pension funds took out as much as they could following Steve webbs changes and encouragement to buy a fast car.

They would have been like my clients and indeed myself in a position of having made pension contributions over the last 30+ years but been utterly disappointed with the performance of the money paid in.

Given the opportunity to take the money out from such a disappointing investment, who could resist.

Of course many will have not understood the tax position and may well have taken out in excess of the tax free lump sum amount, possibly on the advice of ‘financial advisers” (?) and will end up owing tax

I will probably not be here in 30 years time, but if I could place a bet for my children’s benefit, that the new pensions that the government is now encouraging the private sector to take out will fail, just like those of my former clients failed, I would take it.

I agree with a great deal of that

Personally I have considerable disquiet at the enforced enrolment of people in stock exchange based investment, which is what the government seems to be doing with its new pension proposals

And yes, I do have sympathy with old style building socities which can and do provide a valuable social function. I have some savings with one.

Is this idea targetted at just DC private pensions or would you also force DB pensions (state and what few private ones still exist) into this?

Given inflation linked annuity rates are already at all-time lows of 2.5% due to low gilt yields, you need to take a significant amount of risk with your DC pensions to generate a decent lump sum at retirement. If you curtail the tax advantages of DC pensions and/or forced them to buy low returning (albeit more secure) assets then this is likely to suppress the lump sum you generate by retirement.

Anyone with a DC pension would be at an even bigger disadvatange vs. DB pensions. DB pensions have become the ultimate rentier asset given that they generate a risk free income stream which is a multiple of what could be achieved using gilts or an annuity. Do you see this as an issue?

The idea that a pension must be based on considerable amounts of risk is almost oxymoronic and is itself evidence of how wrong our logic that savings can provide pensions for all is

There are two classes of citizen

Those lucky to have DB schemes (and one of the most generous schemes is enjoyed by MP’s themeselves(!) – oh the irony!) and those who have to put up with DC schemes.

The former where the lucky recipient bears virtually no risk (unless the scheme goes bust, which with low interest rates, returns and increasing life expectancy, is a real risk) and the latter where all the risk, worry, decision making is left with the scheme member – he is at the mercy of uncertain asset markets that continue to fluctuate between boom and bust and are at present grossly inflated by levels resulting from low interest rates, QE and the governments addiction to the property market.

It is almost impossible to exaggerate the difference between the two schemes – it’s feast versus famine.

I gave indicated above how poorly I believe DC schemes have performed. As with many markets, the main winners are the middlemen and here read financial advisers who for years hoovered in commissions and who were not averse to recommending products simply on the basis of those that paid the most commission. You now have to pay these professionals on an hourly basis and these fees reduce the value of your pension pot.

The public do not understand financial matters easily. But if the cost of the public sector DB were included in the national debt figures it would add trillions of liabilities.

Because they are so generous, this is the main reason why I am not critical if the 1% public sector pay cap. For it is still a fact that public sectors are better paid than their private sector counterparts when you factor in their better pensions, more generous holidays, more sickness days per year and lastly the fact however useless you are at your job, there is less than 1% chance of being fired – think of bad teachers that are simply moved on to a new school, etc – this would not happen in the private sector

Interesting observation:

“National Savings is the alternative product for many. What’s the plus? The person you’re lending the money to is guaranteed to repay. Plus, they use the money for social purposes and there is no intermediary: the government sells the product and it uses the money.”

Bit like a charity: but bigger, better funded and with universal reach.

But… unlike a charity the government actively doesn’t want more depositors and is trying to run down its activities (which helps to ease the lives of many more millions than all the charities combined).

Funny old world.