The OECD recently published a new report on what they call the labour 'tax wedge' in its member states. This 'wedge' is the estimated tax cost of employing a person in each member state expressed as a percentage part of the total direct cost of doing so.

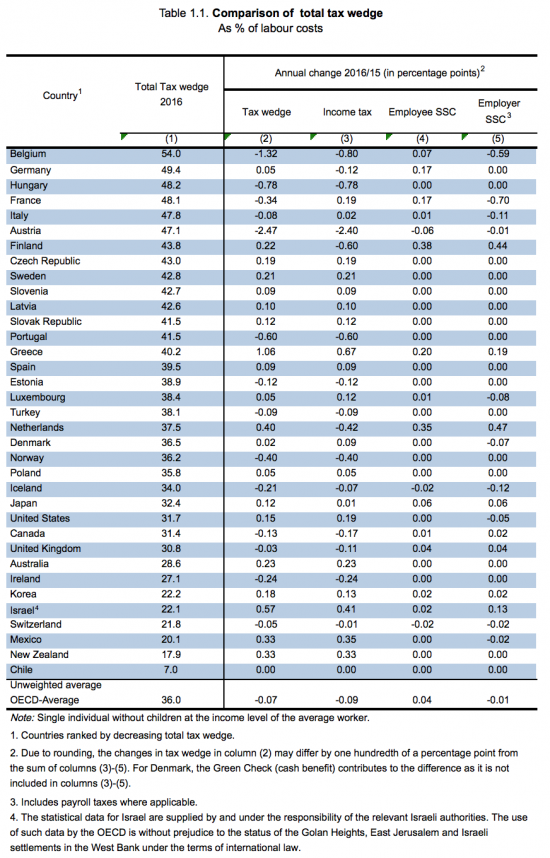

There are actually eight such calculations offered to allow for different personal circumstances and incomes, but the OECD summarises the results as follows and I will use this summary:

First, note that the UK is low on the list at 30.8% and that we are following the current international trend of a very slight reduction in rates.

Second, note that much higher wedges are associated with higher productivity and GDP per head in many (but not all) cases.

Third, let me add another dimension to this issue. This week I am heading for Scotland, in part to discuss issues its tax system faces as a result of voluntary incorporation by the self-employed and disguised-employed seeking to reduce their tax rates. When the difference in effective marginal tax rates, based in the above table, might notionally be in excess of 10%, and even after the new dividend tax are likely to exceed 5% (although differing assumptions have an impact here, and I know it, so please don't spend excessive time nitpicking the point), then the incentive to incorporate is significant.

Ygis incentive to incorporate is also profoundly costly in a number of ways. First, it keeps down wages. The benefit of the tax arbitrage is at least partly captured by employers to reduce wage rates for all employees.

Second, it reduces the incentive to increase productivity: cutting tax through an option the government provides yields better rates of superficial return than investing in equipment or training.

Third, it really does reduce the incentive to invest. Again, assumptions vary across the tax system, because rules on investment reliefs on capital expenditure (technically called capital allowances) vary depending on the size of the spend on capital equipment that a company incurs. The net result us, however, that small companies can often secure a 100% deduction for their spend in the year it is incurred. The corollary is that larger companies, who (pretty much by definition) do most investment (and who also go in for a lot of disguised employment) do not get that relief. They get relief of 18% on the cost they incur in the year they spend (again, I know there are exceptions). But, I stress, that 18% on the cost and us then subject to relief at the prevailing tax rate of 20%. This means that companies in this situation get a saving of 3.6% in tax terms on the kit they buy in a year. To put it another way, tax relief reduces the cost of their £100 outlay in year one to £96.40, which you can fairly call almost utterly irrelevant.

Now I know there are reliefs (reducing ones) in year two onwards but let's be clear: the point has been reached where if a large company wants to save tax then spending money on capital equipment is just about the worst way to do it. Saving money by forcing people into disguised employment and taking part of the benefit provides a considerably better tax rate of return in most cases. Of course it reduces people's security and well-being and it harms investment and leaves the UK's productivity ratings trailing but this is the world of tax incentives we live in, and the economy we have got is the not unsurprising result.

So what to do about it? First, of course, disguised employment that abuses the so-called self-employed person has to end. I have already suggested that changing the tax return to identify those supposedly self-employed with only one client would help identify address this issue. There were howls of protest, no doubt from those heavily invested in the system.

Second, the corporation tax rate should be increased. There is no sense at all in it being lower than the overall employment tax rate. A corporation tax rate of 30% is entirely logical and desirable in a world of growing inequality. If proper country-by-country reporting was undertaken backed by rigorous transfer pricing checks and decent controlled foreign company rules this is entirely sustainable now.

And third, all companies shoukd get 100% capital allowances in their spending as a corollary of the increased tax rate. This means if they spent £100 on capital equipment they woukd get a tax deduction of £30 in the year they did so. That is a real incentive to invest where at present there is almost none.

Changing the tax system by increasing corporation tax rates and capital allowance rates could help provide more secure employment, increase yield, reduce inequality and increase productivity all at the same time. The only obstacle is the obsession with low tax rates that suits the banks and tax cheats but harm the economy as a whole.

As in many issues political leadership is required. A country committed to productivity increases woukd start by removing incentives to cheat taxes. Who is going to say it though?

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

Richard,surely your argument on Corporation Tax on stacks up with an assumed permanence and continued formation of corporate entities and structures. I know you disagree but i contend that a far better solution to our problems is the progressive dissolution of Corporation and even also possibly Income Tax, to be replaced by a Universal sales tax [5-10%??]. In a competitive market this is clearly an unavoidable[?] tax on the supplier and not the consumer. This is only a tax on consumption where there is inadequate competition and as such should encourage investment thereby increasing competition.

Of course I disagree

I am in favour of progressive taxation and your proposal is deeply regressive

If you want to create a more divided and unfair world you have the answer

Under perfect competition (a theoretical construct rather than a scenario which could ever happen in the real world but it’s a useful limiting case) the incidence of a sales tax is on consumers, not producers. The sales tax just gets passed through to the consumer. In its simplest form the tax burden on each consumer would be proportional to expenditure (and hence regressive as a proportion of income in most cases).

And in a situation where monopoly is prevalent that’s just as likely

Thanks Howard

If your argument is correct then why do we experience a chase to the bottom on prices from companies who are able to obviate paying corporation tax. It may well be that under “perfect competition” the “most competitive supplier” will always win and any sales tax is imposed on top of this. However as far as I can see – and from my own business experience – most competitive scenarios drive the supplier to absorb the tax; which is my whole point. It cannot be avoided whereas Corporation Tax can. We are into the conflict between mainstream economics and commonsense psychology here. I can see that turnover [by incurring more gross sales tax] may appear less important to the company which does not pay CT. But pushing up prices to obtain a bigger margin in a competitive situation will not necessarily increase profits regardless of whether there is CT or not. It’s complex!

I hate to tell you that there is very little evidence that most suppliers absorb sales taxes: that is simply not true. VAT is not paid by suppliers for example, odd exceptions around registration points excepted maybe

Once again a very potent post.

Now – if we could find a simple way to get this over to the public?

I hope that some of HM opposition are reading.

OK, I’m no economist, but it appears to me that Scotland should *lower* it’s CT rate compared with rUK (assuming we could) in order to try to level the inward investment playing field between Scotland and England – particularly the south and London. I was in agreement with Salmonds policy of having a Scottish CT rate 3% lower than rUKs.

Isn’t that one of the main tools Eire has successfully used to transform their economy to a state far better than ours? What they lose in the CT swings they make up for in other taxes paid and associated benefits..? It’s tough trying to persuade a company to bypass the “Rome” of the UK (London) and make it’s way 400 mls north to Scotland.

I’m left of centre, btw, but if we don’t get the companies into Scotland in the first place surely it’s moot what we propose taxing them.?

Salmons ferll for the Celtic Tiger myth

And myth it is: the rate was just the ‘for sale’ sign that advertised the low Irtish tax base, and a willingness to turn a blind eye to abuse

That world has changed – as Ireland also knows

And companies don’t go anywhere for low tax: they got for good law, infrastructure, people, IT, training health systems and so much more

Scotland has to sell positives, not negatives

I reckon we may have to differ on this.

Putting up a “for sale” sign sure sounds like a good idea to me if you’re selling something. As for abuse – surely that’s a different issue with a different solution?

The world has indeed changed, but Irish CT hasn’t.

I agree companies want all the things you highlight, not just lower taxes, but your point assumes the English won’t be offering them too. London will be offering them the place where all roads lead to and where around one city twice as many people live than in our whole country. Scotland has to persuade investors to bypass that place, and a view of the Trossachs will only go so far.

Sorry, Richard, but I’m unconvinced on this one.

Irtish CT has changed

Non resident companies are not allowed

Transfer pricing is monitored

You may have noticed what the EU is doing

You can be unconvinced – but if you want to ruin Scotland and its reputation at the same time try to make it a tax haven – and I can assure you it is the road to ruin

I remember the Irish Celtic Tiger economy in the mid-late 1990’s.

I saw what seemed to be kids running the buffet car on a CIE train from Dublin to Tipperary.

I saw the youngest workers ever in the MacDonald’s that were sprouting up every where. It had me thinking. I know that I was not seeing things – a low wage low age economy is what I saw.

And all the new and existing housing was being swallowed up by Germans at the time (inward investment?).

But you only had to see the poor condition of the social housing just south of Dublin railway station to see what was really going on. There were one or two new roads here and there but once you got off those onto the beaten track shall we say, the infrastructure was simply awful.

I’ve never seen pot holes in roads like it. My brother is a lorry driver and I was with him in County Wexford and we hit a pot hole that threw us both out of our seats and he nearly lost control of the truck. This was on a major road in the County.

Had it not been for EU money, I hate to think what Ireland (Eire) would be like now. There just seems to be a criminal amount of neglect over there in what could be one of the best places to live.

I’m not speaking as some snobby Englishman looking down his nose at Ireland either. It’s just that the Irish government – like so many others – think they are here to help the private sector corporations and individuals build nations.

But this is complete tosh. It is proactive and courageous States – working with and setting the rules for all sectors (private and public) in the name of ALL of its citizens that really build nations.

Hi PSR et al

been away for the past 10 days in NI and Donegal mainly driving around in our motorhome, but also a trip to Dublin and back again through Belfast to Scotland. I get to Dublin (my home town) quite a bit but it was interesting to look at Donegal. Dublin seems to be doing very well, but so is London; it was interesting to look at Donegal. I remember the Irish roads in the mid ’90s some short stretches of very nice motorway but once off the main roads they were in a dreadful condition as PSR remembers. I didn’t hold out hope for the Donegal roads but I was astounded. The main road between Letterkenny and Derry was much better than the A1 in Northumberland (Main link between London and Edinburgh and not even dual carriageway apart from short stretches north of Morpeth) and even the B and C roads (T and L roads) were vastly better than our potholed Northumberland roads. Beautifully finished and the repair work seemed to be done properly; lots of hard core – foundations; bypasses around even small towns. Over 1000km of motorway in the Republic now.

Strange the difference 20 years can make. Then again in 1997 I was full of hope for the UK – can’t say the same now.

One thing I find instructive about free market liberals is their lack of faith in people. ‘We must do everything corporations want to attract inward investment’.

Amazon, Starbucks etc must be placated but why? Is it really impossible to sell everyone else’s products on one site and not be called Amazon? Or sell coffee in a cardboard cup and not be called Starbucks? Are they really adding anything new that can’t be replicated and quite straightforwardly (if not easily)?

Scots who want independence can do anything they want if they can persuade enough people to buy what they produce. With an activist govt, a strong university sector, an abundance of basic energy resources, a lot of land and not a large population, and with a very recognisable national ‘brand’ anything is possible. Even complete failure.

Free-marketeers think innovation and enterprise only comes from the big beasts and the rent-seekers and this attitude, so readily repeated in the MSM, destroys creativity. The inward investment mantra is used so uncomprehendingly these days it stops people actually thinking. It’s another example of the TINA attitude.

OK. Rant over.

Welcome rant

@ PhilJoMar

The perverse reality is that these huge corporations depend on the creativity and ‘entrepreneurship’ of much smaller companies and even individuals. Back in the day (a long tiome back but then I’m very old) in general they grew organically. But now it’s much cheaper to buy an on-going business. Additionally the Venture Capital and Private Equity companies swoop on bourgeoning enterprises, develop them and sell them on at inflated P/E ratios. While it’s a bit of a generalisation, I know, but one seriously wonders why successive governments (especially in the UK) haven’t done a lot more to help small business, when it’s the spawning ground for the nation’s economy. As you say, BIG isn’t necessary for the efficient delivery of goods and services nor is it the best chpoice for the environment. Much has been written on the topic and I can’t do justice to it here, but maybe politicians simply prefer working with mega-corporations from a power perspective, even though they don’t generate the tax income and overall social benefits that emanate from smaller commercial enterprises.

I haven’t done this for a while so it’s an opportunity to recommend revisiting ‘Small is Beautiful – A Study of Economics As If People Mattered’ by the late and great Dr Ernst Schumacher. Of course the data has changed over 44 years but the core philosophy is more relevant now than it was in 1973. The 1970s was the critical decade when radical change took hold on western society, with Nixon abandoning the gold standard and the widespread implementation of the neo-liberal dsoctrine.

As you say re Scotland – anything and everything is possible if enough people co-operate to bring it about. Hopefully you/they will North of the Border, but the Sassenachs have sadly lost any co-operative spirit they may have had and are paying an increasingly high price for it. socially and economically.

PS: Not directly relevant but on which planet does the vicar’s daughter live? “… there is a sense that people are coming together and uniting behind the opportunities that lie ahead… our shared interests, our shared ambitions and above all our shared values …”.

I read Small is Beautiful in 1976

Schumacher has a lot to answer for in my life

He was a major contributor to my world view

As usual – apologies for the numerous typos. Fortunately I’m not the only one (no names!).

How dare you!

🙂

@PhilJoMar

Very simple. Economics as espoused by free-market liberals is posited upon humans being rational. They aren’t, and it spoils the economists’ theories 🙂

“There is no sense at all in it being lower than the overall employment tax rate.”

What is the overall employment tax rate? I can see a ‘wedge’ number of 30.8% for the UK in the table, but not an overall employment tax rate.

The wedge rate is that to which I refer

Please don’t criticise my lack of education. I don’t have a university degree, but how does that stack up against this:

“There is no sense at all in it being lower than the overall employment tax rate. A corporation tax rate of 30% is entirely logical . . .”

When I did arithmetic 30.8% was a bigger ratio than 30.0%

The difference between 30% and 30.8% is neither here nor there

The difference between 20% and 30.8%is significant

I am aware that the difference between 30.8 and 30.0 is 0.8. Please do not mock my knowledge of arithmetic. Or my knowledge of the ordering of real numbers.

I am now wondering if you have deliberately chosen a number which ‘makes no sense’ in order to talk down to your readership.

Respectfully, it seems very obvious it is you who is playing games here behind a veil of anonymity

That’s not within this blog’s rules

Surely all taxes on a business (whether VAT or CT) is eventually borne by the customer, long term. If the price doesn’t cover the cost (including the cost of capital, for the risk involved, and including taxes), the activity ceases to be viable and stops.

The customer (rich or poor) eventually pays.

Am not sure I understand how you regard CT as any more progressive than a sales tax/VAT.

CT is, I think, born by capital

The same as IT is born by labour

I am not sure I see your logic

Capital can only bear any cost (whether CT or anything else) in the short term. Long term, if the cost of capital is not covered by the price, the business activity becomes less attractive, and there is less of the thing produced.

Are you saying capital can bear costs indefinitely without eventually passing them on?

What you’re suggesting is capital cannot bear tax

And that is just not true, in my opinion