The Guardian published two stories on Friday concerning the relationship between Northern Rock and its shadow entity, Granite. I'll be candid, I know the stories have been influenced by what's been written here: I was the only source named in the stories.

This led to a fairly mad day on Friday, when in two spare hours between meetings in London I dashed from the studios of Sky to Channel 4 and also recorded radio material for use in the North East.

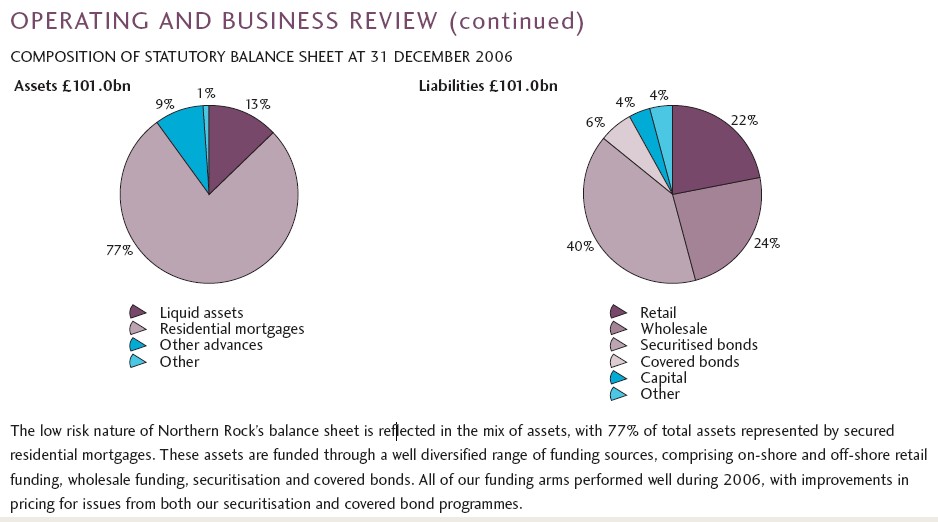

But my media coverage is not the important bit. The Guardian story sought to develop another new angle on this aspect of the story, to add to that on governance and the abuse of charity which have been greatly troubling me. This is that there is a very real problem in the structure of the Granite relationship for the government, now out of pocket to the tune of £24 billion to Northern Rock. Let's go back to the Northern Rock balance sheet, depicted graphically here, and borrowed from its own published accounts:

We now know that £53 billion of the mortgages included in the assets are not owned by Northern Rock at all: they're owned by Granite. That means the 40% of the liabilities on the right hand side aren't liabilities of Northern Rock at all. They're liabilities of Granite. You can ignore the whole "securitised" bit as a consequence. And the covered bonds. And maybe assume that some of the wholesale is also in this category by now. But you also have to remove 53% (because the numbers happen to add to almost exactly £100 billion by chance 1% = £1 billion) from the left hand side - which reduces the 77% of residential mortgages to 24%.

Doing so and recasting the figures out of the reduced total you get a real Northern Rock balance sheet which says that the assets are actually like this:

Residential mortgages, 50%

Liquid assets 28%

Other advances 19%

Other 3%

Now, the liquid assets (otherwise called cash) have gone: there's been a run on the bank. The depositors have taken their money. The "other advances" are poor quality, you can be sure. There's no security for them because we know they're not mortgages. And the remaining mortgages are likely to be lower quality than average for one of two reasons: they're either old and not good enough to include in the securitisation programme or they're new. That also means they're lower quality: it's clear Northern Rock abandoned quality for quantity when offering one in five new mortgages earlier this year. These are going to have an above average default rating: not helped by the fact that the borrowers know they're dealing with a lame institution.

As a result, in terms of security for the loans the value is now likely to be £24 billion of mortgages, with a higher than average default rate likely, and with all the rest of the assets next to worthless or already departed.

What's the problem then? Well, it's this: the Chancellor say that the £24 billion advance is covered by a rock sold £77 billion loan book. Northern Rock says its covered by a £100 billion loan book. And put unsubtly, that simply does not seem to be true. It's covered by a loan book of much less than than and of much lower quality than the whole Northern Rock book. The Bank of England has got the rump end of the assets. And they're worth almost exactly what it has advanced, based on this analysis.

Either that, or it now owns big chunks of Granite debt, in which case we should know, because yet again the risk profile is not the one that has been represented to exist by the Treasury in that case. If the Treasury actually owns Granite debt then it ranks alongside other claimants on that debt, it's not likely to rank above them.

Either way, the Guardian report is right: the debt security of Northern Rock is not as good as has been suggested. It may be much worse than suggested. And the line of credit may really be at its limit. Which explains the panic about selling the shares in the bank, a policy which in itself represents a wholly misguided understanding of the importance of equity in a situation such as this when the creditors have to come first.

And whatever Northern Rock says about this structure being well known to the City, it remains shocking to anyone else who has not been corrupted by the City's way of thinking. And the use by Northern Rock of a structure designed to ensure its City financiers walked away without risk if it went bust has left the government more exposed than it might otherwise be as lender of last resort. And let's be unambiguous about this: that is exactly what was intended. Which is a story that needs to be told, and I'm glad to have played a part in doing so.

NB Story updated 9.40 am 26.11.07

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

I agree that the pledged assets are not those assigned to the bond vehicles, and clearly the Granite ones are better quality. Geneally, they’re older (hence more likely to be secured on less geared mortgages (thanks to the rise in property values) and inevitably the portfolio has been cherry-picked for quality assets probably leaving the ‘dregs’.

I think you are missing the most vital point – the one which surely is keeping every one up at night — you really need to look at the prospectus for the bonds ———— what covenants have been given by the *issuer* Northern Rock to the bondholders and / or to Granite, and what would trigger them, as it may oblige the issue the redeem *all* the bonds at 100 pct.

Well, actually there’s another angle to this.

Tim Congdon let the cat out of the bag here

http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/ddf4c35e-88e5-11dc-84c9-0000779fd2ac.html

Particularly this

“The explanation is that the Bank of England can create money “by a stroke of the pen”.

Parliament has made it the UK’s only issuer of legal-tender notes, and it can expand the note issue or credit a balance convertible into notes at virtually nil cost.

Because of these special powers, the Bank does not need to borrow in the interbank market at a positive interest rate.”

What this means is that the Bank of England may create credit, either in the form of Bank Notes, or alternatively, in the form of account balances exchangeable for Bank Notes, and this is exactly what the Bank of England has been doing to the tune of £23 billion, created “by a stroke of a pen” and thereupon loaned to Northern Rock.

This freshly minted money does not derive from the “tax-payer” at all: it is simply interest-free credit — so-called “Fiat Money” – that any Central Bank may create at any time to oil the wheels of commerce, but conventionally will only do so as cash.

The Bank of England is charging Northern Rock a “penal” rate of 7% pa for the use of this credit, of which 5.75% – the current Bank “base rate” – is actually collected while the “penalty” of 1.25% on top of this is not in fact being paid to the Bank of England but is being “rolled up” as a Debt from Northern Rock to the UK Treasury — a “subordinated loan” which ranks after all other creditors but before the shareholders.

In other words the Bank of England is gifting this “investment” to the Treasury on behalf of “tax-payers”.

Suppose everything goes wrong and Northern Rock suffers catastrophic losses from its secured lending. The first to lose are the Northern Rock shareholders: then it’s the Treasury’s turn in relation to their “Subordinated Loan”. But this is hardly a “loss” to the UK tax-payer since they would be losing an asset which they have been gifted by the Bank of England to the Treasury on their behalf.

What about the tens of billions of tax-payers’ money exercising the UK politicians and the press so heavily?

Well actually, no. This money has been created by a stroke of a pen, or more likely, a click of a mouse and it never was our hard earned “tax-payer’s money” in the first place.

The effect is exactly as though the Bank of England were to take back a few more skip-loads of time-expired bank notes and burn them in the usual way.

In summary, the UK tax payer can lose NOTHING in the event of a default. It is rare indeed that the mask slips in relation to the truly surreal nature of the vacuum at the heart of Central Banking.

The truth is that the longer that the Northern Rock fiasco goes on, the better off the tax-payer will be.

That’s right, this isn’t a disaster for the long-suffering “tax-payer”, it’s a potential goldmine.

You probably meant “we now know that £53 billion” rather than “million” in your paragraph below the pie-chart figure.

Richard

True

I’ll correct it

Richard

Chris Cook: clearly you believe that the BoE can magic real resources out of thin air just by printing banknotes or giving a line of credit convertible into banknotes, at zero cost to anyone? Good news for the government, then, they could finance any level of expenditure without any need for tax? Or have you ever heard of, or been subjected yourself to, the inflation tax?

Who said anything about real resources? We are talking banking here, after all.

Money in fact has no cost. We have been bamboozled into thinking that it does because our current money is created and issued as Debt.

Credit has a cost, consisting of system costs and default costs.

Capital has a price, consisting of the return investors are prepared to pay commensurate with risk. Which is as low as 1.5% for 50 year index-linked gilts and 3% for (non index-linked) US Treasuries.

Neither the Cost of Credit nor the Cost of Capital bears any relationship to a Central Bank set rate of Interest unless Money is issued as Debt, and even then, as we see, the relationship may break down.

Currently our banking system manufactures credit – in the case of private banks, this is interest-bearing credit – based upon an amount of Capital set by the Bank of International Settlement.

But it can be manufactured – as the Bank of England is doing – equally well by a central Bank directly, as non interest-bearing credit, backed by an implicit government guarantee.

We see in Zimbabwe the problems that can arise if money is minted ad lib and goes into circulation. An inflation tax, as you say.

It is the deficit basis of our money that causes asset price inflation.

However, where such credit is created as interest-bearing loans (as it customarily is) it is obviously more costly, and hence more inflationary, than if it is issued directly to “capital users” under the supervision of (say) a monetary authority, or with banks as managers of credit creation.

The money created by the Bank of England in the Northern Rock case is not going into circulation, and nor is it being used to “bid up” asset prices.

It is simply extinguishing existing bank-created interest-bearing debt and remains “tied up” in land and buildings.

Very few people truly understand the banking system, and newspapers will not (with rare slips of the mask) print anything about the truth of the system, since it appears to be regarded as form of financial pornography: an Indecent Truth, perhaps.

Remember monetarism. Increasing the supply of money will continue the failed policies that got us here. Creditors should have been allowed to lose money by Rock going into administration. The new money will feed back through into asset inflation – not housing this time – but commodities. Excessive money supply (excessively low interest rates (below RPI), excess credit creation by banks and Government creation of fiat money as with Rock). A long slowdown as we get Labour’s 1970’s style stagflation is now on the cards.

[…] about the deception that the Granite structure represents. Nothing has changed what I have written here: I contend that is right, but the government still seems to deny it. Worse, the government is now […]

what on earth has the chicanery of government monetary policy got to do with Northern Rock? Nothing like keeping to the point!

Once the Government underwrote the depositors then nationalisation was inevitable. That it took so long to secure the related assets may well demonstrate similar incompetence that you see when Governments print money, but is not the same thing at all.

And the suggestion that money has no cost is the most ludicrous half-witted theory I have heard in a long time. If you really believe that then please explain why most people do not have enough of it? After all if it is free then surely there would be no shortage!

Alastair

Respectfully, Lord Keynes and J K Galbraith would not agree with you regarding the cost of money.

Maybe you need to open your mind to the reality of money.

Richard

Skimming through the Legal Notices Section of the Times, as one does, although I’m not really sure why, I couldn’t help but notice the voluntary liquidation of one Granite Mortgages. Surely this can’t be the same ‘Granite’ as the shadowy subsidiary of Northern Rock, into which it quietly squirreled away some £53 billion of its mortgage stock? Can anyone shed any light?

jerry rommer