The Tax Research glossary seeks to explain the terms used on this blog that refer to more technical aspects of economics, accounting and tax. It recognises that understanding these terms is critical to understanding the economic issues that affect us all the time.

Like the rest of the Tax Research blog, this glossary is written by Richard Murphy unless there is a note to the contrary. It is normative approach and reflects post-Keynesian, heterodox economic opinion with a bias towards modern monetary theory. The fact that many items in that sentence are hyperlinked shows that they are explained in the glossary.

The copyright notices pertaining to the Tax Research blog apply to this glossary.

The glossary is designed to achieve three goals:

- It seeks to provide a short, hopefully straightforward, definition of what a term might mean.

- It then seeks, when appropriate, to explain what the term means within the context in which it is used. This is meant to elaborate the definition to add to understanding.

- It then critiques the term, explaining, if appropriate, what the weaknesses inherent in the term or the situation it describes are. The aim here is to empower the reader to understand the issues behind the nonsense that most professions create around their activity to provide them with a mystique that they rarely deserve and which often hides what they are really up to.

The glossary is not complete. It will grow over time. If you think there are entries that need adding please let me know by emailing glossary@taxresearch.org.uk. Please also feel free to suggest edits. The best way to do this is to copy an entry into Word and then send me a track-changed document indicating the changes that you suggest.

Because of the way in which it is coded this glossary automatically cross refers entries within itself and to the blog that it supports and within the glossary itself but if you think a link is missing please let me know.

Finally, if you like this glossary then you might like to buy me a coffee. It has required the support of a fair few to write it. You can do so here.

Glossary Entries

A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z |

- Saving

- Secrecy Jurisdiction

- Secrecy provider

- Secrecy space

- Sectoral balances

- Settlor

- Settlor Benefit

- Share Capital

- Share capital

- Share Premium

- Shareholder

- Shareholder equity

- Shares

- Shell bank

- Shell corporation

- Social capital

- Social security

- Socialism

- Source basis taxation

- Spahn taxation

- Stakeholder

- Stakeholders of a tax system

- Statement of Affairs

- Stock and work in progress

- Supply and Demand Curves

- Supply side reforms

- Sustainable cost accounting

Saving

Money laid aside by its owner out of use for a period of time as they do not wish to use it to fund their spending at that moment.

Savings take money out of circulation. As a result saving reduces the amount of economic activity in an economy. It does so by reducing the multiplier effect in that economy because saving effectively stops money circulating within it. As a result, savings have a negative macroeconomic impact on growth however sensible they might be for the person making them.

Secrecy Jurisdiction

A secrecy jurisdiction is a place that intentionally creates regulation for the primary benefit and use of those not resident in its geographical domain with that regulation being designed to undermine the legislation or regulation of another jurisdiction and with the secrecy jurisdiction also creating a deliberate, legally backed veil of secrecy that ensures that those from outside the jurisdiction making use of its regulation cannot be identified to be doing so.

See also tax haven.

Secrecy provider

Secrecy providers are the lawyers, accountants, bankers, trust companies and others who provide the services needed to manage transactions in the secrecy space created by a secrecy jurisdiction or tax haven. Offshore could not operate without the existence of these firms.

Secrecy space

Secrecy spaces are unregulated spaces that are created by a secrecy jurisdiction that are suggested to be outside their domain and so are treated by them as being ‘elsewhere' or ‘no-where'. Both of these are domains without geographic existence.

For a longer explanation, see here.

Sectoral balances

Sectoral balances describe a macroeconomic accounting framework that shows how the financial positions of the main sectors of an economy are interrelated when stated in their own currency, and why they must sum to zero.

In any economy, total financial surpluses and deficits must balance. One sector's surplus is necessarily another sector's deficit. This is not a theory or a policy preference. It is an accounting identity that holds at all times.

The framework is most commonly presented using three broad sectors:

-

The government sector

Central and local government, including the public sector as a whole.

-

The private domestic sector

Households and businesses combined.

-

The foreign sector

The rest of the world, captured through the trade and current account balance.

That said, it is also possible and often analytically useful to split the private domestic sector into households and the commercial (or corporate) sector. This allows more precise analysis of whether deficits and surpluses are being driven by household borrowing, corporate investment behaviour, or retained profits. As a matter of fact the UK government conventionally reports sectoral balances using four sectors:

- government,

- households,

- corporations, and

- the rest of the world.

This disaggregation helps identify where financial stress or excess saving is actually occurring within the economy.

The sectoral balances identity can be stated simply:

Government balance + Private sector balance + Foreign sector balance = 0

Or, when disaggregated:

Government + Households + Corporations + Foreign sector = 0

Several implications follow.

First, government deficits are not inherently problematic. When the private sector wishes to save, for example, during a period of uncertainty or recession, or when the country runs a trade deficit, a government deficit is the mechanism that allows those savings to exist. Attempting to eliminate the government deficit under such conditions can only force the private sector into debt, a move that is usually economically unwise.

Second, trade deficits matter. If a country imports more than it exports, the foreign sector is in surplus. Unless the government runs a deficit to offset this, the private domestic sector, households, firms, or both, must run a deficit instead. Understanding this is vital, but commentators or politicians rarely refer to it.

Third, austerity has predictable effects. Cutting public spending or raising taxes to reduce government deficits does not remove deficits from the economy. It transfers them to households and firms. The result is usually weaker demand, higher private indebtedness, and greater financial instability. Austerity is, therefore, almost always economically counterproductive.

Fourth, “balancing the books” for government is not analogous to household budgeting. Households cannot create net financial assets for the rest of the economy. Governments that issue their own currency can. Sectoral balances explain why treating public finance as if it were household finance is conceptually wrong.

The sectoral balances framework is most closely associated with the work of Wynne Godley, whose analysis proved prescient in identifying the unsustainable private debt dynamics that preceded the global financial crisis.

Within the Funding the Future framework, sectoral balances are central to understanding:

-

Why public deficits often reflect private saving preferences.

-

How financial instability emerges when household or corporate deficits persist, or when governments react inappropriately to them.

-

Why fiscal rules that target arbitrary deficit limits are economically illiterate.

-

How governments can support stability, care, and capital maintenance across the whole economy

Sectoral balances do not tell governments what they should do. They explain what must be true. Sound economic policy begins by respecting these constraints, rather than denying them.

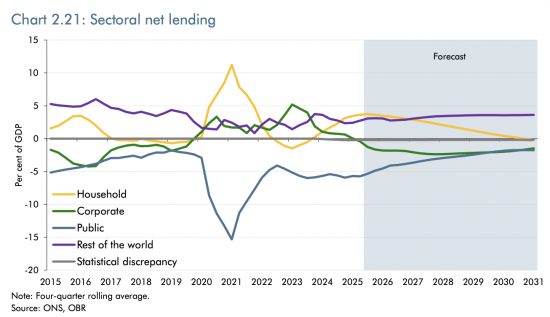

Sectoral balances are frequently portrayed as a chart. This one comes from the UK government's Office for Budget Responsibility forecasts published in November 2025:

The balances above zero represent sectors in surplus and that are saving, and those below zero represent sectors in deficit or borrowing.

The balances always equal zero. The moral is that for every saver there must be a borrower, as double-entry bookkeeping also makes clear, thereby emphasising the accounting logic that must be reflected in sound economic management.

Settlor

The person who establishes a trust by gifting assets to it.

Having made the gift, a settlor is usually supposed to have no further influence over a trust but in many tax havens / secrecy jurisdictions that is not the case and the settlor often remains in complete control of the assets of the trust despite having supposedly gifted them for the benefit of others. These trust arrangements can be considered to be shams by some other jurisdictions.

Settlor Benefit

Any benefit from a trust that is returned to the settlor.

Under UK law such benefits are prohibited but many tax haven / secrecy jurisdiction locations permit the creation of trusts from which the settlor may benefit as a beneficiary or by way of return of the trust property. There is some doubt about whether arrangements of this sort can properly be considered to be trusts. They might instead be considered shams but without access to detailed knowledge of the trust arrangements that can be hard to prove.

Share Capital

The total value of shares issued in a company.

Accounted for as part of shareholder equity by a company.

Includes any share premium on the issue of shares.

Share capital

The total value of shares issued in a company. This may include any share premium (see separate entry).

Share Premium

The difference between the price paid to a company for a share and its nominal price as set by the company. If a £1 share is issued by a company for £5 then the share premium is £4.

Share premiums are usually paid when shares are issued later in the life of a company when the original shares issued by it will have risen in value. The share premium is intended to create equity between all shareholders by requiring that they broadly equally contribute for their share compared to the value of the company as a whole at the time of the share's issue.

Share premiums represent part of shareholder equity on the balance sheet of a company for accounting purposes.

Shareholder

The owner of a share or shares in a company or corporation.

In many instances, the registered shareholders of companies are nominees which prevents identification of the real-life beneficial owners.

Registers of beneficial ownership are meant to address this issue, but none do so effectively as yet, not least because only the holders of stakes of more than 25% are usually required to be disclosed and this rule is easy to arbitrage or evade.

Shareholders do not own the assets of the company in which they own a share and have no claim over those assets unless the company is liquidation when in most instances companies are insolvent with few if any funds then being available for distribution to shareholders.

Shareholders are entirely dependent upon the decision of the directors of the company in which they invest for the payment of dividends: they cannot enforce a claim to be paid, even by passing a resolution in an annual general meeting. They would have to replace the directors instead, which in most quoted companies almost never happens as a result of a shareholder resolution.

As such the idea that a company is run in the interest of shareholders makes little sense, and nor do the ideas behind the concept of shareholder value have any substance to them.

This fact also makes a mockery of the idea that an auditor should address their audit report to the shareholders of a company when those shareholders have one of the weakest relationships with a company amongst all its stakeholders.

Shareholder equity

Shareholder equity is the total value of a company attributable to shareholders. This is equivalent to the net asset value of the company i.e. its total assets less its total liabilities.

Total shareholder equity is usually made up of the total of:

- Share capital

- Share premiums

- Reserves

- The cumulative total of net profits less net losses and dividends paid over the life of the company (see profit and loss account).

It is important to note that this sum is not a liability owing to shareholders and that they have no legal right to claim it from the company despite their notional ownership of it. The figure is instead the notional sum that would be due to them in the event of the winding up of the company assuming that all the assets and liabilities were then worth the sums attributed to them on the balance sheet, which is very rarely the case in that situation. The figure is therefore a measure of the change in the value of the capital of the company over time but has no other meaning

Shares

The capital issued by a company subdivided into individual units of nominal value that it decides upon (e.g. £1 each) that are then issued to shareholders as indication of their ownership of a stake in the company, each of which individual subdivided units is called a share.

See also company, corporation and shareholders, share capital and shareholder equity.

Shell bank

A bank without a physical presence or employees in the jurisdiction in which it was incorporated.

Shell corporation

A limited liability entity usually formed in a tax haven or secrecy jurisdiction (including the UK and USA) for the purposes of hiding illicit financial flows, tax evasion or regulatory abuse.

The shell corporation is highly unlikely to have a real trade. Its sole purpose is to hide transactions from view.

No one knows how many such corporations there are, but they are commonplace.

Other names for such entities are sometimes used e.g. ‘brass plate companies', indicating a legal entity whose only real presence is the plaque on the wall of a lawyer's office recording the location of its registered office.

Effective registrars of companies requiring a full range of documents, including details of beneficial owners and nominee directors and nominee shareholders for all entities registered in a jurisdiction to be on public record, are the way to address the abuse created by shell corporations and brass plate companies.

Social capital

Social capital is the stock of institutions, relationships, norms and shared understandings that enable cooperation, trust and collective economic activity.

It includes:

- public institutions,

- democratic systems,

- legal frameworks,

- administrative competence,

- social cohesion, and

- shared expectations of fairness and reciprocity.

Social capital underpins all economic activity.

Markets require trust, enforceable contracts and legitimate authority.

Money requires collective belief and institutional backing.

Investment requires stability, predictability and social consent.

Where social capital is strong, economies are more resilient, adaptive and inclusive.

Social capital is depleted by:

- inequality,

- corruption,

- exclusion,

- privatisation of public purpose, and

- the erosion of democratic accountability.

These processes weaken economic coordination and legitimacy, even when they appear to increase short-term efficiency or profitability.

Maintaining social capital requires sustained investment in:

- public institutions,

- representation,

- transparency,

- fairness,

- and shared purpose.

When social capital is run down, economic activity becomes increasingly extractive, coercive and unstable, relying on enforcement rather than consent and producing diminishing returns over time.

Related posts:

- Capital

- Capital maintenance concepts

- Financial capital

- Physical capital

- Human capital

- Social capital

- Sustainable cost accounting

- Income

Social security

I have long thought that one of the quietest acts of political vandalism in modern Britain was the change of language that sought to turn social security into welfare. It happened slowly. It sounded harmless. It was anything but that.

There is a good reason for saying that, because once you persuade people that a system of mutual protection is a handout, you make it easy to cut. You make it easy to stigmatise. You make it easy to pretend that those who need help are the problem, and so deny that the reality is that the economy has failed them.

That linguistic shift has shaped decades of policy, and we are living with the consequences.

A system built because markets fail

Social security did not appear by accident. It was created because industrial capitalism exposed risks that individuals could not manage alone.

People get ill. They lose jobs. They age. They care for children or parents. They face disability. They experience economic shocks that have nothing to do with their effort or virtue.

No private insurance market can cover those risks universally at an affordable price. And no family can bear them alone in a complex economy.

So societies did something rational. They pooled risk.

When we are able, we contribute. When we need help, we receive support. Over a lifetime, most people do both. That is not charity. It is collective insurance.

And in macroeconomic terms, it is essential infrastructure because when income collapses in a recession, social security replaces part of that income. Spending continues. Businesses survive. Communities hold together.

Without it, downturns become depressions. The economic jigsaw falls apart because too many pieces vanish at once.

A system that recognises care

Markets measure what is paid. Societies depend on what is not.

Parents raising children, carers supporting elderly relatives, and volunteers sustaining communities: none of these appears in GDP, and yet without them, the economy could not function for a week.

Social security acknowledges that reality. It supports carers. It supports families. It supports those whose contribution is socially essential but not market-priced.

This is what I mean by the politics of care. That is an economy exists to sustain people, not to maximise transactions. To dismiss that as welfare is to deny the value of care itself.

A system we all use

The mythology of welfare depends on the idea that there are two groups: taxpayers who contribute and claimants.

There are not. Firstly, social security is paid by the state, and not with taxpayers' funds. Tax, as always, controls the resulting risk of inflation arising from a payment made by a government with the power to create its own currency. Secondly, most of us use a social security system at some time.

We contribute to balance the economic equation when we are working and healthy. We receive when we are ill, unemployed, caring for someone, or retired.

We benefit when our children go to school, when our parents receive pensions, and when our neighbours are supported through hard times instead of falling into destitution.

Social security smooths income across the life cycle. It redistributes risk from the unlucky to the lucky. It creates stability that markets cannot provide. That is not a moral failing. It is the basis of civilisation.

Why the word “welfare” was chosen

The word welfare was not adopted because it was accurate. It was adopted because it was useful to those who wanted to shrink the state and expand private wealth. It allowed politicians to say:

- Support is a favour, and not a right.

- Claimants are suspects prone to fraud, idleness and doubt.

- Cuts are discipline, and not harm

- Poverty is a chosen behaviour, and not the result of political policy intended to create economic failure.

That rhetoric has justified austerity. It has justified sanctions regimes. It has justified humiliating systems that cost more to administer than they save. And it distracted attention from the real transfers in our economy, whether from labour to capital, or from tenants to landlords, or from the state to tax avoiders.

The politics of language has, in this case, as it has too often, concealed the economics of power.

Social security as capital maintenance

On this blog, I have argued that we need to think in terms of maintaining all forms of capital, not just financial wealth. Capital includes:

Social security maintains the last two.

It keeps people healthy enough to work, learn, and care. It keeps communities intact when shocks hit both individually and collectively. It prevents the destruction of skills, relationships, and hope.

Cutting social security is not about saving money. It is running down the national wealth in the most literal sense.

We would never boast about letting bridges collapse to save steel. Yet we boast about letting people fall into poverty to save pounds.

What follows from this

If we were honest about what social security is, policy would look different.

We would accept that support should be adequate, because underfunded insurance does not insure.

We would remove stigma and complexity, because humiliation is not efficient.

We would fund social security and then address any need to counter inflation by imposing progressive taxation, including tackling the avoidance and evasion that drain public capacity.

We would properly integrate social security with housing, health, and care policies, recognising that insecurity in one domain spreads to others.

And we would stop using a word designed to make people ashamed of needing help.

Conclusion

Language matters. Narrative matters. And economics, as I often say, is full of CRAp, or completely rubbish approximations to the truth when it pretends that markets alone can secure well-being.

Social security is one of the institutions that proves otherwise. It is a recognition that we are interdependent, that risk is shared, and that care is an economic necessity.

Call it welfare if you want to undermine it.

Call it social security if you want an economy that works for people.

Socialism

Socialism is a system of economic organisation in which the purpose of economic activity is the promotion of the well-being of people and the stability of the society they form, rather than the accumulation of private wealth.

It begins from the premise that the essential foundations of life, such as health, education, care, housing security, energy, water, and the monetary system itself, are too important to be left to markets whose priorities are profit, scarcity, and exclusion.

It then builds from this idea to create a broad range of ideas and approaches that typically include:

-

Collective responsibility for essential services which are provided as public goods — universal, state-funded, and free at the point of use — because a decent society cannot function without them.

-

Democratic control over key economic issues, requiring that policy on and major decisions about essential services, investment, energy, infrastructure, and money creation are made through accountable public bodies or cooperative structures, and not by unregulated private actors.

-

Limits on extraction and rent-seeking. Socialism aims to reduce the power of those who live off the returns of ownership rather than on sums earned by contributing, shifting rewards as a result away from rent, speculation, and monopoly profit extraction towards labour, care, and productive activity.

-

A commitment to equality. Socialism requires that the distribution of income and wealth in a society reflect social priorities rather than market accidents. It uses taxation, labour rights enforced by law, and public ownership and market regulation to achieve this outcome.

-

Plural forms of ownership. Public, cooperative, mutual, municipal, and small-scale private ownership can all co-exist within a socialist society and economy. What matters is that ownership structures serve a social purpose rather than impose private power.

-

A rejection of the idea that markets represent freedom. Socialism argues that real freedom requires security, education, health, time, and agency, all of which are things that markets alone cannot guarantee.

These approaches do require a caveat to prevent misinterpretation. Socialism does not abolish markets. Nor does it imagine an all-powerful state. Rather, it defines the appropriate roles of each.

The result is that socialism treats markets as tools, not masters, recognising that markets can work well for non-essential goods, most especially when abundance, competition, and choice genuinely exist, but markets are unreliable, and often harmful, when applied to life-critical systems such as health, care, housing, education, core infrastructure, pensions, energy, and the monetary foundations of the economy.

Because of this, in a socialist system:

-

Markets operate within clearly defined boundaries, and only where they generate genuine social benefit.

-

They are regulated to prevent monopoly power, labour exploitation, ecological damage, and financial instability.

-

A diverse ecology of ownership, including small private firms, cooperatives, municipal companies, community enterprises and even larger corporate entities - so long as they are genuinely accountable and appropriately governed - can operate inside regulated markets, so long as none accumulates the power to impose outcomes on society.

-

In sectors where markets fail by design, including the provision of public goods, universal services, long-term investment, and environmental security, democratic planning and public provision necessarily take precedence.

Socialism also sees the state as the institutional expression of society's collective will, and not an intruder into economic life. A socialist state is neither authoritarian nor omnipresent; it is an enabling and coordinating structure through which people make shared decisions.

The state's role is:

-

Protective, ensuring basic security and universal access to essential services.

-

Enabling, providing infrastructure, investment, and long-term planning that markets avoid.

-

Disciplinary, preventing the concentration of private power and curbing rent extraction.

-

Democratising, extending shared ownership and public accountability where essential services or core economic infrastructure are concerned.

Put together, these principles define socialism as a mixed, democratic economic order utilising markets where appropriate and public provision where necessary within a state organised to secure social purpose rather than private privilege.

Source basis taxation

Source basis taxation charges income to tax in the jurisdiction where it is earned.

Source-basis taxation should be compared with residence-basis taxation and unitary-basis taxation.

Under double tax treaty rules, income attributable to a permanent establishment in a jurisdiction is usually taxable at source i.e. in the country where it is earned.

If the person earning that income is also resident in another jurisdiction then it is commonplace for that other jurisdiction where they are resident to also have the right to charge tax in that same source of income, having given credit for tax already paid in the country in which it was sourced.

So, for example, if £100 was earned in country X by the permanent establishment of company A Ltd in that place, on which income country X wishes to charge 15% tax meaning £15 is paid, and then country Y in which company A Ltd is resident wishes to charge the same income to tax at 20% there it can do so, but only after giving credit for the £15 already paid in country X, meaning country Y collects another £5 in tax.

Some countries only tax on a source basis, and consider income earned outside the country exempt. This is commonplace in flat tax systems.

Others tax on the basis of both source and residence (subject to a foreign tax credit) to ensure a more comprehensive approach and to tackle obvious opportunities for tax avoidance arising from shifting a source of income out of a country if a residence basis is used.

Rules can also vary for differing types of income: for example dividends are always deemed to have been taxed at source in the EU and are tax-free in the country of residence of the recipient whether tax has been charged or not at source. This has been abused by countries like Ireland, Luxembourg and the Netherlands, all of which are corporate tax havens.

Compare with residence basis taxation and unitary basis taxation.

Spahn taxation

The Spahn tax is a proposed system for taxing foreign exchange transactions in order to reduce harmful financial speculation. It was developed by German economist Paul Bernd Spahn as an alternative to the Tobin tax, or an addition to it.

Spahn argued that a flat-rate transaction tax, as James Tobin proposed, risked penalising routine, low-risk currency trades that facilitate international trade and long-term investment. Instead, he suggested a two-tier system:

-

A very low basic tax rate

This would apply to all foreign exchange transactions. Its purpose is not to stop trade or long-term investment, but to provide a small friction that slightly slows down high-frequency speculative activity and raises some revenue.

-

A high, variable surcharge

This would only apply in periods of excessive exchange-rate volatility, when speculation becomes predatory and destabilising. The surcharge acts as a circuit-breaker, helping central banks prevent destabilising capital flows without banning foreign exchange activity.

The key innovation is that the surcharge only triggers under specific market conditions, which are identified and enforced by regulation or automated systems.

Spahn taxation sits within a wider set of tools, including capital controls, aimed at protecting countries from speculative attacks that can destroy economic stability. From my politics of care perspective that underpins Funding the Future, Spahn taxation recognises that financial markets serve society, not the other way around. Markets should not be allowed to impose crises on democratic economies in the pursuit of private profit.

The broader implication is that currencies are public goods. Their stability is essential to everyday life, wages, savings, pensions and investment. Spahn taxation helps ensure that those who try to profit from volatility bear a cost while those engaged in genuine trade and investment are largely unaffected.

Stakeholder

A stakeholder is a person impacted by or with an interest in or concern about the activities of another person or entity.

The stakeholders of companies, corporations and other reporting entities are likely to be:

- The owners of its capital

- Other suppliers of capital to the reporting entity

- Trading partners of the reporting entity

- Employees of the reporting entity

- Regulators

- Tax authorities

- Civil society in all its forms including local authorities, journalists, academics, civil society groups and individuals.

In the case of most companies, corporations or reporting entities many stakeholders are likely to have more interest in the activities of a company because of its potential impact on their well-being than the owners of its capital.

Despite that, the International Financial Reporting Standards Foundation has ruled through its International Accounting Standards Board that its accounting standards need only meet the needs of shareholders and other owners or suppliers of capital to a company and that the needs of other stakeholders need not be considered in the course of preparing accounts of financial statements.

See also stakeholders of a tax system.

Stakeholders of a tax system

The stakeholders of a tax system are generally considered to be:

- The government of a jurisdiction;

- The legislators of that jurisdiction who are not in the government;

- The tax authority of a jurisdiction;

- The electorate of that jurisdiction;

- Taxpayers within a jurisdiction, whether they are within the electorate, or not;

- Researchers, whether they are academics, journalists, civil society or those from other backgrounds;

- International agencies and others in countries other than the jurisdiction being reviewed.

See also tax transparency framework.

Statement of Affairs

Stock and work in progress

In UK accounting terms stock refers to the value of physical commodities owned by a company for use in its production process or for direct onward sale to customers. An example might be the unsold goods sitting on supermarket shelves.

In US accounting terms, these items are referred to as inventory.

Work in progress (WIP) is usually grouped with stock or inventory in the presentation of accounts. It represents the value of incomplete work undertaken on the creation of goods or services intended for supplied to a customer on an accounting reference date. Work in progress may be physical, such as partly manufactured goods, or intangible, such as the value of time expended by staff that will be billed to clients in due course.

Both stock and work in progress should be valued at the lower of their cost of production or their net realisable value, i.e. what they might be sold for less the cost of their completion for sale in the following accounting period.

Supply and Demand Curves

The image of two intersecting curves — one sloping down for demand, one sloping up for supply — is perhaps the most famous in economics. It is presented as the key to understanding all markets. Yet this tidy diagram bears little resemblance to the messy, dynamic world we inhabit.

Assumption

The theory suggests that when prices rise, buyers want less of whatever is on offer, while sellers want more. The market, therefore, finds an equilibrium price at which the two meet. Everything, from wages to food prices, is supposedly explained by this simple balancing act. The diagram gives the illusion of universal truth and mathematical elegance.

Reality

In real life, demand does not always fall as price rises. People often buy expensive goods precisely because they are expensive. Luxury brands, property in fashionable postcodes, or speculative assets like Bitcoin are all of this type. Economists call these Veblen goods or Giffen goods, but they are not exceptions; they are central features of modern economies built on status and scarcity.

On the supply side, things are no simpler. Production cannot adjust instantly. A farmer cannot grow new crops overnight because demand rises; a factory cannot double capacity without investment.

In labour markets, supply is shaped by contracts, health, family responsibilities and the sheer need to survive. What is more, people cannot simply supply more labour when wages fall; they may instead drop out of work altogether.

Why It Matters

When policymakers treat these curves as literal descriptions of behaviour, they misdiagnose problems. Inflation, for example, is often blamed on too much demand when supply bottlenecks, corporate profiteering, or external shocks such as energy prices are really driving it.

Central banks raise interest rates to cool demand, punishing households instead of tackling the real sources of cost pressure.

The curves also hide power: employers and landlords can often dictate terms regardless of supposed equilibrium. These curves ignore the realities of political economy.

Understanding this means recognising that markets are not natural balancing systems but arenas of negotiation, regulation and struggle.

Summary

Supply and demand curves are teaching tools, not truths, and real markets rarely obey their geometry. This economic myth does not extend beyond the classroom, but its implications have, at a cost to us all.

Supply side reforms

The removal of regulations on business so that they might pursue profit irrespective of the externalities or costs that they might impose on others in society both at the present point in time and in the future.

Sustainable cost accounting

1 - Sustainable cost accounting (SCA)

Sustainable cost accounting (SCA) is a proposed accounting method and reporting framework designed to bring the costs and liabilities of achieving environmental sustainability (most notably net-zero by 2050) into the audited financial statements of an organisation, rather than leaving them in narrative sustainability reporting or voluntary disclosures.

It was created by Richard Murphy. The latest full-length explanation is available here.

At its core, SCA is “a method of accounting for the liabilities that must be incurred” if an entity is to remove all scope 1, 2 and 3 carbon from its supply chain and onwards sales chain and meet its net-zero target, using provisioning and a new Statement of Sustainability to track movements in a sustainability provision, mirrored by a sustainability reserve within equity.

SCA is, at heart, a form of capital maintenance concept. It does not abolish IFRS reporting; it overlays an additional, overarching environmental capital maintenance concept on top of existing financial and physical capital maintenance reporting, and then requires that the consequences of that additional maintenance duty be made visible through specific balance sheet and equity reserve structures.

1- What SCA is trying to fix

SCA starts from the observation that, even after COP26-era commitments, corporate accounts typically under-report or do not report the future costs required to meet net-zero obligations. That omission has a predictable consequence: it allows distributions (dividends, share buybacks, etc.) to continue, while the resources required for future climate investment are depleted. SCA's purpose is therefore twofold:

- truthful accounting (bringing the cost reality implied by climate science into “true and fair” reporting), and the creation of

- behavioural incentives (shifting entities away from distributions and towards investment by making the cost visible now).

3 - The mechanism: provisioning + sustainability reserve + Statement of Sustainability

SCA's core technical move is the mandatory recognition of a sustainability provision for the estimated full cost of delivering the entity's sustainability plan (i.e. achieving net-zero alignment), with a corresponding sustainability reserve within equity. The reserve is designed to reduce distributable reserves: it is intentionally constructed so that recognising the environmental obligation constrains the amounts that management can credibly present as available for distribution to shareholders.

To make this operational and intelligible, SCA adds a new primary statement: the Statement of Sustainability, which reports movements in the sustainability provision (and therefore in the sustainability reserve), in the same way that the income statement and statement of comprehensive income report movements relevant to other capital maintenance concepts. A set of financial statements with SCA reporting included provides disclosure on compliance with three capital maintenance concepts:

A key design feature is that SCA seeks not to “break” existing reporting literacy. It separates movements through:

- the income statement (primarily aligned with physical capital maintenance / historic-cost logic),

- the statement of comprehensive income (aligned with financial capital maintenance / fair value logic), and

- the Statement of Sustainability (aligned with environmental capital maintenance via the sustainability provision).

4 - Materiality in SCA: from single materiality to double and dynamic materiality

SCA's materiality concept within its proposed accounting framework is not an optional add-on; it is structurally central.

a. Single materiality is rejected as inadequate for environmental accounting

SCA argues that ISSB-style approaches are “essentially voluntary” in practice because they allow entities to decide whether climate issues are material, often using single materiality tests derived from financial capital maintenance reporting. SCA treats that as inadequate for the scale and temporality of the problem.

b. Double materiality is required

SCA adopts double materiality: the entity must report both:

- the impact of environmental change on the entity (outside-in), and

- the impact of the entity on the climate/environment (inside-out).

Crucially, double materiality is framed as expanding the conventional idea that information is material if it is of use to a narrow investor/creditor user group and replacing it with an obligation to consider materiality in the context of all potential users of financial statements.

c. Dynamic materiality is required

SCA does, in addition, explicitly incorporate dynamic materiality: impacts that are not yet financially material under conventional tests that usually only consider a twelve-month time horizon for risk appraisal may, very obviously, become so over longer periods of time and therefore must be anticipated in financial reporting rather than left to future write-downs or crisis disclosures. This longer time horizon is defined as dynamic and is not limited in duration.

d. The test is tougher: double reasonableness

SCA's disclosure threshold uses a double reasonableness test. It asks whether a reasonable person might hold the view that disclosure is reasonably required, in the process explicitly raising the hurdle compared to the usual single-reasonableness framing for material disclosures.

e. Prudence becomes a precautionary principle

SCA converts prudence (caution under uncertainty) into an explicit precautionary principle. Practically, this tightens what counts as acceptable evidence in sustainability planning and reporting. As a result, the use of carbon offsets is constrained, and unproven-at-scale technologies cannot be treated as a dependable solution for the delivery of net zero on which a reporting entity might rely. The purpose is both:

- objective: to improve auditability and comparability, and

- subjective: to incentivise earlier action rather than delay.

6 - Temporality: why SCA compounds instead of discounting

SCA identifies a temporal mismatch: conventional accounting commonly discounts future obligations, while ecological costs can be non-linear and escalating. SCA therefore rejects discounting for these liabilities and instead requires compounding of any unexpended sustainability provision balances to reflect the increasing costs of delay, rising harm, and the tightening deadlines as 2050 approaches. It proposes using the higher of 5% or the entity's weighted average cost of capital as the compound rate.

This is not a technical quirk. It is an explicit attempt to align the temporality of accounting judgement with the temporality of environmental risk and policy constraint.

7 - Distributable reserves: making the constraint explicit

SCA treats the ability to distribute as central to going concern appraisal in an environmental capital maintenance world. It therefore requires explicit disclosure of distributable reserves and requires that sustainability liabilities be treated as charges against those distributable sums unless the entity can disclose alternative sources of capital to fund its transition. The intention is direct: if you have to finance adaptation out of retained profit, you cannot simultaneously pretend those same reserves are freely available for dividends and buybacks.

8 - Carbon (environmental) insolvency: a new failure mode

SCA introduces carbon/environmental insolvency as a condition arising when an entity cannot demonstrate how it will command the capital and capability to eliminate adverse environmental impacts by 2050 while still meeting financial liabilities as they fall due in the meantime. This does not necessarily imply immediate cash insolvency; it is a long-horizon going-concern failure revealed by the environmental capital maintenance test. SCA then requires directors to disclose how they will respond to the carbon insolvency of their entity, whether through adaptation, fundraising, diversification, or wind down, because disclosure is itself an obligation under this framework.

9 - Conclusion

SCA is not “sustainability reporting”. It is a proposal to make environmental obligation accounting-real: by redefining materiality in both double and dynamic terms, by redefining temporality (i.e. by compounding and not discounting liabilities for et zero adaptation), and by redefining reserves distributability (by ensuring reserves are constrained by the sustainability provision), it forces the financial statements to reveal whether an entity is truly a going concern in a net-zero world. That is its importance, and simultaneously the challenge it poses to all large reporting entities to which it might apply. Their denial of the reality of the world in which they are operating is no longer sustainable. Their need to plan for net-zero survival becomes exploit, and disclosable within their financial statements.

Related posts:

- Capital

- Capital maintenance concepts

- Financial capital

- Physical capital

- Human capital

- Social capital

- Environmental capital

- Sustainable cost accounting

- Income

Buy me a coffee!

Buy me a coffee!