I posted this new glossary entry yesterday afternoon. I was astonished to find I had not written an entry on sectoral balances before now, so I made good the deficit.

Sectoral balances describe a macroeconomic accounting framework that shows how the financial positions of the main sectors of an economy are interrelated when stated in their own currency, and why they must sum to zero.

In any economy, total financial surpluses and deficits must balance. One sector's surplus is necessarily another sector's deficit. This is not a theory or a policy preference. It is an accounting identity that holds at all times.

The framework is most commonly presented using three broad sectors:

-

The government sector

Central and local government, including the public sector as a whole.

-

The private domestic sector

Households and businesses combined.

-

The foreign sector

The rest of the world, captured through the trade and current account balance.

That said, it is also possible and often analytically useful to split the private domestic sector into households and the commercial (or corporate) sector. This allows more precise analysis of whether deficits and surpluses are being driven by household borrowing, corporate investment behaviour, or retained profits. As a matter of fact the UK government conventionally reports sectoral balances using four sectors:

- government,

- households,

- corporations, and

- the rest of the world.

This disaggregation helps identify where financial stress or excess saving is actually occurring within the economy.

The sectoral balances identity can be stated simply:

Government balance + Private sector balance + Foreign sector balance = 0

Or, when disaggregated:

Government + Households + Corporations + Foreign sector = 0

Several implications follow.

First, government deficits are not inherently problematic. When the private sector wishes to save, for example, during a period of uncertainty or recession, or when the country runs a trade deficit, a government deficit is the mechanism that allows those savings to exist. Attempting to eliminate the government deficit under such conditions can only force the private sector into debt, a move that is usually economically unwise.

Second, trade deficits matter. If a country imports more than it exports, the foreign sector is in surplus. Unless the government runs a deficit to offset this, the private domestic sector, households, firms, or both, must run a deficit instead. Understanding this is vital, but commentators or politicians rarely refer to it.

Third, austerity has predictable effects. Cutting public spending or raising taxes to reduce government deficits does not remove deficits from the economy. It transfers them to households and firms. The result is usually weaker demand, higher private indebtedness, and greater financial instability. Austerity is, therefore, almost always economically counterproductive.

Fourth, “balancing the books” for government is not analogous to household budgeting. Households cannot create net financial assets for the rest of the economy. Governments that issue their own currency can. Sectoral balances explain why treating public finance as if it were household finance is conceptually wrong.

The sectoral balances framework is most closely associated with the work of Wynne Godley, whose analysis proved prescient in identifying the unsustainable private debt dynamics that preceded the global financial crisis.

Within the Funding the Future framework, sectoral balances are central to understanding:

-

Why public deficits often reflect private saving preferences.

-

How financial instability emerges when household or corporate deficits persist, or when governments react inappropriately to them.

-

Why fiscal rules that target arbitrary deficit limits are economically illiterate.

-

How governments can support stability, care, and capital maintenance across the whole economy

Sectoral balances do not tell governments what they should do. They explain what must be true. Sound economic policy begins by respecting these constraints, rather than denying them.

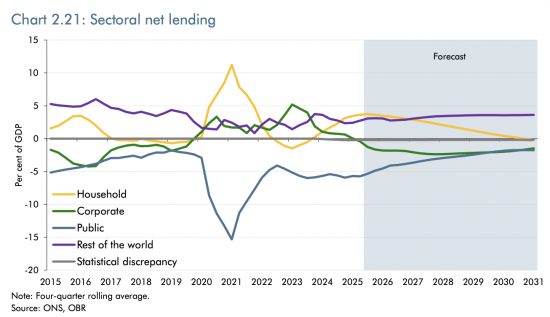

Sectoral balances are frequently portrayed as a chart. This one comes from the UK government's Office for Budget Responsibility forecasts published in November 2025:

The balances above zero represent sectors in surplus and that are saving, and those below zero represent sectors in deficit or borrowing.

The balances always equal zero. The moral is that for every saver there must be a borrower, as double-entry bookkeeping also makes clear, thereby emphasising the accounting logic that must be reflected in sound economic management.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

There are links to this blog's glossary in the above post that explain technical terms used in it. Follow them for more explanations.

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

Buy me a coffee!

Buy me a coffee!

Really helpful, thank you

A useful post thanks, but I have concerns.

I would note that the sectoral balances sum to zero only if you include the government “debt”. But why would anyone not include government debt?

Including the government debt appears to make sense if it is funded by bonds. But funding government debt by bonds is part of the neoliberal trope, treating the government as a household. It implicitly accepts the idea that money is created by the private sector and governments need to borrow, need to have government debt, to fund themselves. That is not true.

A better choice of how to finance the “debt” is via a central bank overdraft, which used to be, and in extremis still is, how the government can fund itself. Selling bonds, rather than using an overdraft is a government choice to sanction rent extraction by the, wealthy, bond holders.

But a central bank overdraft is also very misleading. The government cannot really have a meaningful overdraft with the central bank, because it owns the bank. What is really happening, if the bank claims an overdraft with the central bank, is that that money has been created by the central bank. The overdraft can, and in my opinion should, be cancelled at any time with no substantive effect. I would argue that government debt should not be considered a debt in the normal sense, but merely a record of total money created. Words matter; calling it debt is misleading.

Perhaps, one might say, this is just picking, but I do not think so. Is this, perhaps, a case where we have to be very careful with terminology to avoid confusion and to avoid inadvertently arguing in neoliberal terms? What is needed, IMO, is a change in our thinking that acknowledges the reality of sovereign money creation and destruction. I worry that this view of sectoral balances reinforces neoliberal myths. 🙁

Tim

The government balance can be described or funded whichever way you like: it is always the sum of net government spending less taxation, and it has to be in the equation beause the equatuon is about money and it is the money supply.

I think you have this wrong because you aopear to be denying the money supply exists. Why?

And for the record, this has nothing to do with neoliberalism. Like MMT, this descrobes what is. It is an accounting identity.

Richard

“What advantages derive from the system of book-keeping by double entry? It is among the finest inventions of the human mind; every prudent household should introduce it into their economy.” (From J. W. Goethe)

Yes double entry bookkeeping is great for households, companies, local authorities, in fact anyone except the government.

I question whether it is applicable to overall government spending because the government can create or destroy money.

Don’t be absurd Tim.

The whole problem with government economic management is that it does not use double entry and so pretends there are no real economic constraints.

You have your analysis exactly the wrong way round. It does not use double entry and that is the problem.

I may well be wrong. If so, it is because I don’t understand and explanation would be most welcome. 🙂

To me, double entry bookkeeping implies money is conserved, that is it is neither created or destroyed. It’s like the conservation of energy, momentum, or electric charge in physics. So double entry makes sense in the general economy.

The government creates and destroys money. So I’m struggling to see how double entry bookkeeping applies there. To me it leads to situations as in QE, where the government buys it’s own debt and claims to owe itself money (via the BoE). Or it can lead to the situation of the government having an overdraft with the BoE and, thereby, owes itself money. I really struggle to see how that makes sense.

So perhaps I’m confused. If so I expect others are too. I know people struggle to understand QE. An explainer would be most welcome. 🙂

Double entry book-keeping is a language.

The only thing it implies is that every transaction has a reaction: to transact there are always two parties involved and the appraisal of the consequence for each has to be considered, as does the dual consequence within the entity also require recording. That is it.

It is not about money: double entry can and does record vast numbers of transactions denominated in money but where cash is not involved. All credit transactions are if that nature, but there are many more.

To pretend that double entry implies neoliberalism is as big a category error as to claim using English does: it is as absurd as that. It reveals a total misundertsanding of what double entry is.

And for the record, money creation cannot happen without double entry: indeed, fiat money cannot exist without it, to show how wrong you are.

I have written about the double entry of this process. See https://www.taxresearch.org.uk/Blog/2022/06/21/the-double-entry-behind-the-money-creation-in-the-central-bank-reserve-accounts/

And I have explained QE. It is in the Glossary under QE and try this blog post. https://www.taxresearch.org.uk/Blog/the-qe-process/

Tim, your assertion makes no sense. Single entry bookkeeping, where debits don’t need to be matched exactly by credits, leaves the records wide open to manipulation. If you want evidence: a classic example is the annual GERS report (which presents a deliberately distorted picture of income and expenditure in Scotland) and which was dreamt up by a Tory Minister at Westminster as a means of discrediting the notion of Scotland ever being able to survive as an independent nation without the “generous financing” of Westminster.

Year after year it’s been proven to be a work of fiction (or bullshit, if you prefer) and year after year its been discredited by umpteen analysts. The only GERS mystery is why the SNP Scottish Government doesn’t simply discontinue its publication. It would save the costs of its production (by a third party religiously following the instructions of its creator) and that saving could be used to fund worthwhile projects in Scotland.

Thanks, Ken.

Hi Richard,

Oh dear, this does seem to be getting a bit involved. 🙁 I replied to Ken before I saw your 3:43pm reply to me, so there may appear to be some repetition. I fear I am being irritating for which I apologise. I really really am not trying to simply be argumentative. I really do think there is a genuine problem in the way that the economics of money creation and destruction are described. 🙁

I re-read “The double entry behind the money creation in the central bank reserve accounts”. In that post you say, “Of course, the Bank of England has to also record that transaction in the Consolidated Fund of which the DWP forms a part, but from its perspective this transaction is a debit – the government owes that sum to it.”. That is where I, and perhaps others, have a problem. That’s because it really doesn’t make sense to me that the government should owe, have a debt to, the Bank of England, which it owns. One might say that this is just accounting and perhaps that is obvious to you with your expertise and background, but it is not obvious to me and, perhaps, others. This is particularly the case for me because, in several other places, when discussing total government debt, you explain that the total government debt is not as high as it at first appears because it includes government bonds held by the bank of England. Saying that these bonds don’t count, with which I agree, is confusing taken together with saying “the government owes that sum to [the Bank of England”. Those statements, taken at face value, don’t seem to be compatible.

I also re-read your post on “The QE process”, in which you say, “the government does as a consequence owe the central bank in exactly the same way as it might if the loan had been left outstanding at the end of stage one of this process”. And this is the same issue, that it appears that the government owes itself money (via the BoE). I just can’t get my head around the idea of the government, or anyone else, owing themselves money; it doesn’t seem logical.

……….

Tim

If you want to live in a world that does not exist, please feel free to do so. but don’t waste my time with it.

The debt with the central bank is anyway just a step on the way. If we got rid of the central bank and consolidated the entry there would still be a debt, it would just be in pension cost, or whatever might have been expended. You will never, ever get that unless you want a governmment with no financial contols, no records, and an opprtunity for rampant fraud.

Your choice, but I have spent enough time on your refusal to undertand. There has to come a time when I say enough, and I think i have reached it. I can only suggest that right now you are way out of your depth and are refusing to put in the hours to comprehend it. I suggest you do before posting again, but your comments ae nonsense.

Richard

Interesting when you look at the sectoral balance chart above that the OBR produces and the ones that Stephanie Kelton uses, that the public graph line is the mirror image of the others which has to prove that only when the public sector is in deficit can the others be in positive!

What seems to be getting lost here is that double‑entry isn’t a philosophical claim about who “really” owes what to whom. It’s simply the discipline of recording flows so that we can see what has happened inside the system. When the government spends, something is created; when it taxes, something is destroyed. Those changes have to be recorded somewhere, otherwise we lose the ability to track the consequences of policy.

The fact that the government owns the central bank doesn’t remove the need for that record‑keeping. If anything, it makes it more important. Without a liability entry somewhere in the system, we would have no way of knowing how much new money had been injected, what it had funded, or how it relates to the rest of the economy. The “debt” to the central bank isn’t a real-world burden; it’s simply the accounting mirror of the asset that now exists in the private sector.

In other words, double‑entry isn’t there to constrain government in a neoliberal sense. It’s there to prevent the opposite problem: a world where money is created, spent and extinguished with no audit trail, no transparency and no way of understanding the sectoral consequences. The balances have to sum to zero because that’s how we keep track of who holds the financial claims created by government action.

Seen that way, the whole thing becomes much less mysterious. The government doesn’t meaningfully “owe itself” anything — but the accounting system still has to show where the money went, who holds the corresponding asset, and how it fits into the wider economy.

Thank you.

You had more patience than me today. I admit to having felt frazzled for much of it.

I think focusing on these “Accounting/Economic identities” is useful.

First, their truth is undeniable…. or should be.

Second, it exposes the absurdity of the ‘morality tale’ that always accompanies discussion about debt and deficits.

Eg. If you demand everyone saves how do you square it with “sum to zero”? How can you square having GDP as your main priority…. and insist on cutting the budget deficit? Etc.

It’s easy to say what you want…. but these identies require you to say what you will give up.

Agreed

Could a fifth group, that sit between home and corporate, become more significant in this equation moving forward. I’m referring to the ultra wealthy who don’t really work and don’t have significant input to running business, but are living off their assets?

The data would be unreliable.