In 1993, the economist Richard Auty coined the term “resource curse” to describe the paradox that countries with abundant natural resources often grow more slowly and less equitably than those without. The United Kingdom is not usually placed in that category. In my opinion, it should be.

What happened to Britain from the early 1980s onwards was not an accidental encounter with the resource curse. It was a deliberate political choice. Thatcher's then Tory government, with vast North Sea revenues, chose to use them not to renew the industrial fabric of the country but to destroy it. That is the first part of the story.

The second is that as the oil and gas ran down, finance took their place as the source of a new curse, and the consequences of both still shape our economy today.

Let me explain those suggestions.

First, the Thatcher government inherited a windfall that few states in modern history have enjoyed. North Sea oil and gas revenues surged just as what looked like a government-generated recession hit. Rather than being used to modernise British manufacturing, rebuild infrastructure, or create sovereign wealth for future generations, oil and gas revenues were channelled into funding mass unemployment, cutting taxes for the wealthy, and, most importantly, sustaining an industrial closure programme that hollowed out much of Britain's productive capacity. Britain burned its future to fund the anti-socialist neoliberal project.

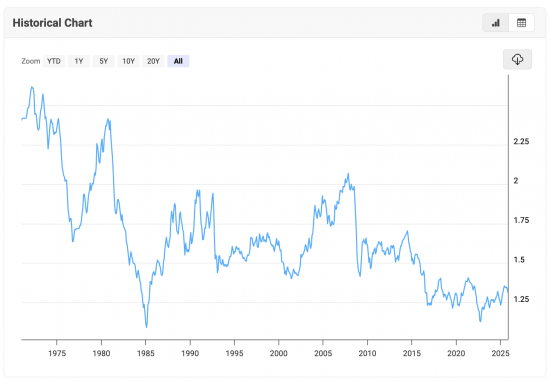

Second, the early 1980s saw another consequence of the resource windfall: after initial shocks, sterling increased in value, a trend that continued against all the odds until the time of the global financial crisis in 2008, with Brexit being the only thing that broke the trend:![]()

Exchange rates rise when an economy is flooded with demand for its currency from abroad, in this case, first of all, as a result of oil and then as a consequence of an over-inflated financial sector.

A strong pound may feel like a source of pride, but for manufacturing, it is fatal. British exports became increasingly uncompetitive as a result. Our cost base rose whilst domestic producers faced a flood of cheaper imports. Entire sectors from shipbuilding to steel, engineering, textiles, and electronics were pushed into decline. The government blamed unions and inefficiency, but the artificially inflated exchange rate did most of the work.

Third, the finance added to the woes. Once the oil bonanza began to fade, the City of London became the new engine of growth, and again, not by accident but by design. The Big Bang of 1986, deregulation, and the embedding of the UK's tax haven network were deliberate strategies to attract global hot money. Britain exported industrial goods in 1970. It exported financial claims by 2000. One is rooted in real work. The other is rooted in rent.

Fourth, the Bank of England has been complicit in this story for four decades. Interest rates were kept high under Thatcher to attract global capital. That inflated the pound further and, by increasing the UK cost base, accelerated deindustrialisation. And now, even as inflation has fallen, the Bank's programme of quantitative tightening once again props up excessive interest rates, strengthens sterling, and damages British exporters who have never recovered from the first wave of destruction.

The result is an economy with a persistent growth problem. But, crucially, it also has a structural problem: our currency is consistently overvalued because our economic strategy still depends on attracting foreign money rather than building domestic capacity.

That creates consequences.

To begin with, Britain remains addicted to hot money. Interest rates that are higher than economic conditions suggest are appropriate only serve one purpose, which is to pull in speculative capital. The Bank of England denies this, but the evidence is plain. Too often, when sterling dips, interest rate expectations mysteriously rise. This is not inflation control. It is exchange rate engineering.

Next, industry still pays the price. A strong pound squeezes exporters, discourages investment, and pushes production offshore. Businesses that might otherwise thrive in a stable, low-rate, competitive-currency environment instead shrink, automate prematurely, or disappear entirely. The UK's chronic trade deficits are not a mystery; they are a policy outcome.

A further consequence is regional inequality. When finance becomes the dominant sector, wealth is sucked into the City's Square Mile and its satellites. The rest of the country, and most especially the former industrial regions, are still left with the legacies of the 1980s. They are low productivity, insecure employment, and a lack of coherent industrial strategy. The oil and gas curse became the finance curse, which then morphed into a geography of decline.

And finally, democracy suffers. When a state builds its economy on global capital flows, it becomes hostage to them. Governments fear market reactions. Ministers speak of credibility with investors, not accountability to citizens. Economic policy becomes an exercise in appeasing bond traders and currency markets, even when those policies are harmful, unnecessary, or irrational. That is precisely what we see now. Fiscal rules are designed to reassure markets, and not to meet social need; interest rates are detached from economic reality; and the political culture treats finance as its master rather than treating it as a servant.

What does all this mean?

First, Britain needs to abandon the fantasy that an economy built on attracting hot money can ever be stable or prosperous. Finance must be put back in its place as a utility, and not be seen as the ruler we must serve.

Second, the Bank of England must stop using interest rates as a substitute for industrial strategy. High rates do not create productivity. They destroy it. Quantitative tightening should end. Interest rates must reflect domestic conditions and not the demands of global capital.

Third, we need a modern industrial strategy with a competitive pound at its heart. That means targeting full employment, supporting investment through lower borrowing costs, and using public banks to channel savings into productive activity and not speculation.

Fourth, we need to dismantle the UK's tax haven infrastructure. It serves only one purpose, which is to keep Britain attractive to mobile financial wealth while undermining our own tax base and distorting our exchange rate.

And last, we need to tell the truth. Britain did not decline because workers were inefficient or because industry was hopeless. Britain declined because governments chose finance over production, speculation over investment, and short-term political advantage over long-term national prosperity.

The oil and gas curse was real. The finance curse that followed has been even worse. We can break both, but only if we admit that they exist, understand how they interact, and decide to build an economy based on real work, fair reward and democratic control. That is our task now.

Comments

When commenting, please take note of this blog's comment policy, which is available here. Contravening this policy will result in comments being deleted before or after initial publication at the editor's sole discretion and without explanation being required or offered.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

There are links to this blog's glossary in the above post that explain technical terms used in it. Follow them for more explanations.

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

Buy me a coffee!

Buy me a coffee!

Looking at Europe, only the Netherlands & Norway have substantial Oil & Gas fields.

Norway has done very well investing its oil revenues, I cant comment on the Dutch economy.

Meanwhile France with very limited indigenous fossil fuel seems to have done well – and of course specialises in small economic cars and in the same way resource poor Korea has become an industrial power house

What is going to happen when the oil and gas revenues run out – and the end is coming

I lived through those times, your narrative makes sense of it. I have not over the years been able to name comprehensively all that had gone wrong, but the consequences were clear to see, and can still be seen. Halfway through mind-numbing amounts of training for work so I’m not really functioning today but this piece went straight to the heart of the matter.

Thanks

And good luck.

Excellent analysis, much better and more concise than most academic commentary.

I wince when I hear that phrase ‘Britain is open for business”. Open to selling off our assets.

I started work with a local insurance broker at 16 and heard a conversation between the partners that the govt forced banks to prioritise lending for growing industry and businesses by offering easier and cheaper rates. This was mid sixties. If they were right, then I guess this changed with the Thatcher ‘reforms’.

I read of people being allowed to borrow to take over other businesses -like Manchester United or Boots-load the debt on them and squeeze pay to maximise the profits to shareholders. Does the govt. need more powers to deal with this-or is it they could but don’t?

Succinct. Inarguable.

Like Anne S – I lived through all this – the analysis rings true. I’m not qualified to comment further.

Brilliant, so clear and damning. Could you get this into, say, the Guardian as an opinion piece? It needs to be more widely seen.

Also, would you consider making a glossary entry for hot money? Having looked it up, I see it has a specific meaning which is not quite what I thought it meant.

The Guardian very rarely accepts any contributions these days.

In theory the oil and gas energy resources should have improved our industrial capacity but other factors were in play both national (trying to balance the government’s books by issuing treasury bonds because it’s believed government operates on a credit card) and global (some countries trying to achieve price point in markets by resorting to class war on steroids which can plainly be viewed as “closet wars”!

https://www.noahpinion.blog/p/book-review-trade-wars-are-class

As someone who saw his father’s firm taken over by foreign ‘investment’ and then wound up I can only heartily agree with your post. The consequences for my family were quite severe and I am sure that we were not the only ones.

This is the real ‘truth-social’ , never mind what the orange numpty in U.S. calls that stream of bullshit he writes on there.

What you describe is a legally enforced system of theft. Nothing more.

And if that is true, what of the ‘democracy’ that presided over it all?

The answer is that there was not democracy. Ever. It was just words. One thing going to university taught me was that despite the words spoken, one must always watch the money? That is where power and ‘democracy’ always betrays itself.

It is time start again. From the ground up.