I posted this thread on Twitter last June, but it is just as relevant today:

There has been much discussion about the likely failure of Thames Water in the last day or so. I've been looking at the accounts of England's water companies for the last twenty years. My conclusion is that they are all environmentally insolvent. So, a thread…..

There are nine companies in England that take away sewage. There are more that supply water alone. But the crisis that the English water companies face largely relates to sewage so my work has looked at the ones that take our waste away.

Thames Water is one of those sewage companies. The others are Anglian Water, Northumbrian Water, Severn Trent, South West Water, Southern Water, United Utilities, Wessex Water and Yorkshire Water.

It's important to say that although I used the accounts of each of these companies in my work, the results I am talking about here or for the industry as a whole. To get a proper picture of the water and sewage industry I combined their accounts into one single set.

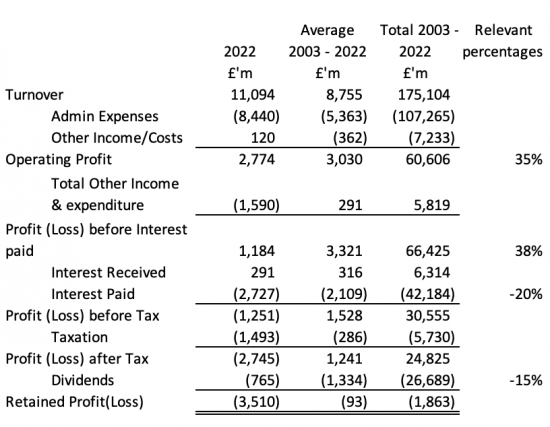

Doing so produced some quite astonishing data. This is what the profit and loss accounts of the combined water and sewage companies of the UK looks like for 2022 in isolation, for 2003 to 2022 in total, and on average over that period:

There is a lot of data there. There are, however, some straightforward facts to concentrate on.

Firstly, the operating profit margin in this industry is 35%. That is staggeringly high, and it goes up to 38% when other income is taken into account. 38p in every pound you pay for water is operating profit i.e. profit before the cost of borrowing.

Second, note the cost of borrowing. I have generously offset interest received against interest paid. That still leaves interest costs representing an average 20% of income. 20p in every pound paid to these companies, on average, goes on interest.

That still leaves them profitable, though. And they do pay tax. The average tax rate is 19%, but that is way below the expected tax rate for this period when the tax rate was as high as 30% for some of it. And much of that tax has not been paid: more than £8bn has been deferred.

Finally, of the almost £25 billion they have made in profit over the years they have paid out every penny, and more, in dividends. In other words, the shareholders have taken 15p in every pound paid for water. There was nothing left for reinvestment, at all.

No wonder the water industry is in trouble. The income statement shows that the public is being fleeced by these companies who are simply treating the fact that the English consumer has had no choice as to who to buy water from as a means to extract profit from them.

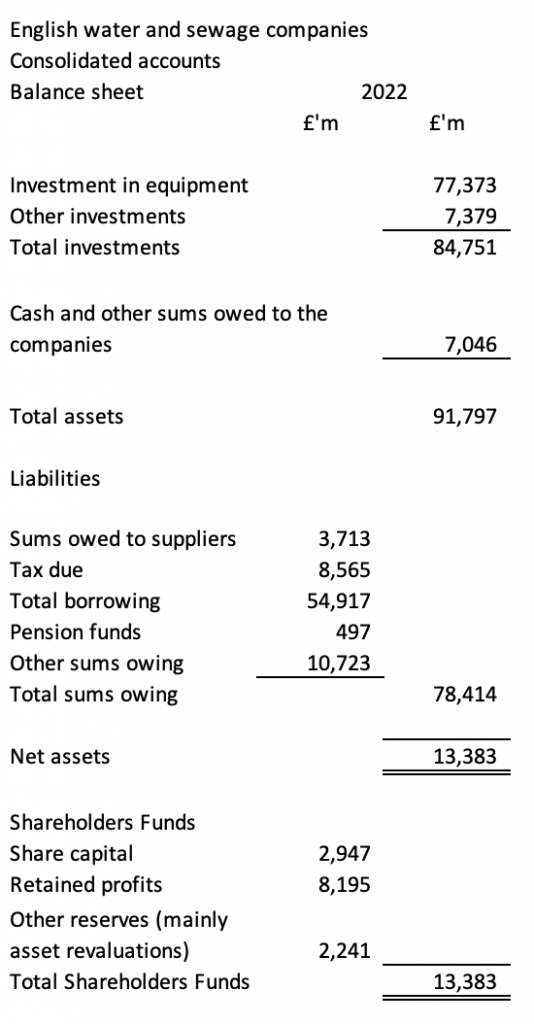

Things are, if anything, worse if I look at the balance sheets. Now I know these scare most people, so I will talk through the details. This is a very summarised balance sheet for the industry in 2022:

The industry has £77 billion invested in equipment. The rest of its assets are some financial investments, a bit of cash and sums owing to it from customers. So far, so good.

What is scary is what the industry owes. The £77 billion of equipment is financed, in the main by borrowings of almost £55 billion, or more. It's also funded by the tax not yet due of more than £8.5 billion, which brings down the cash-paid tax rate of the industry considerably.

Even the pension funds of those working for the industry are contributing to the funding, and there is more borrowing of various sorts in the other sums owing, totalling more than £10.7 billion.

What this means is that of the total near enough £91 billion invested in the sector more than £78 billion is funded by borrowing or sums owing of some sort and only just over £13 billion is funded by the shareholders.

What that also means is that the shareholders provide less than 15% of the overall funding for this industry. So much for the idea that private capital would fund water after privatisation. The reality is that borrowing is doing so.

When I began to look at the data in more depth things only began to get worse. What I was really interested in knowing was how much the water companies had invested in equipment over the twenty years reviewed.

The answer was, in my best estimate, that sum was £89.8 billion. Of course, some of that has now worn out and has long gone from the accounts. Assets like vans and computers do not last that long in use.

Then I worked out how that investment was funded. There were just two ways. One was out of operating income. For the technically minded, this is possible using what is called the depreciation charge in the accounts. This sum amounted to £38.9 billion. Customers provide this money

The rest of the funding came from the increase in borrowing over the period. That amounted to £40.5 billion. Other long-term liabilities, which are again mainly borrowing or pension fund liabilities, increased over the same period by £10.4 billion.

The net result is that of the £89.8bn invested, customers or borrowing of various sorts provided £89.8bn of the funding, meaning the shareholders effectively made no investment in the assets of these businesses at all.

This matters for one very good reason. As we all know, these businesses are now routinely polluting England's rivers and beaches with sewage. That sewage comes from what are called storm overflows, although that's a misnomer now, as many release sewage even after modest rainfall.

That pollution cannot persist. Unless it is stopped we will end up without reliable clean water in England. The estimated costs of ending this pollution do, however, vary considerably.

The industry has offered to invest £10 billion over seven years, or £1.4 billion a year. The government has decided that £56 billion is required over 27 years, or just over £2 billion a year. The trouble is neither sum will come close to getting rid of the crap in England's water.

The House of Lords looked at this issue based on independent analysis and concluded that the most likely estimate of the cost of getting rid of all the pollution in our water was £260 billion. And that needs to be done as soon as possible. I suggest ten years.

If that investment of £260 billion was made, we might have clean water in ten years.

What the industry is offering is something quite different. Even if they meet the government's demand of them, at best I estimate that based on officially published data they might cut the crap in water by two-thirds, at best, by 2050.

So why has the government set such a low investment target that still leaves us with polluted water? The only possible answer is that they wanted to make sure that the private water companies would not go bust by having to spend too much.

Let me put that another way. The government thinks that saving the private water companies is more important than them polluting our water, rivers and beaches with all the costs that will create.

The government has made the wrong decision. But if the required £260 billion was spent (with more required to become net zero compliant) then the water companies would go bust. What that means is that they are environmentally insolvent.

The concept of environmental insolvency applies to any business that cannot adapt to make its business environmentally friendly – as climate change and ending pollution requires – and still make a profit. What it means is that its business model is bankrupt.

That is where the English water industry is now. Thames Water might be facing environmental bankruptcy, but this industry as a whole is in my opinion incapable of funding the investment required to deliver clean water and be profitable.

The government might be making noises about taking Thames Water into temporary public ownership, but that is meaningless when Thames Water can never be profitable and deliver clean water. There is only one answer for this industry now, and that is nationalisation.

I would suggest that this nationalisation should be without any compensation to shareholders. That is because their businesses are environmentally insolvent. Providers of loans might also have to take a hit too: they made a bad decision lending to these companies.

The government will then have to support the industry using borrowed funds. I suggest it should issue water bonds via ISAs to the public to do this. Wouldn't you want to save in a way that ensures we all get clean water in the future? I would.

And the way in which water is charged for might have to change. The idea that we all pay the same price per unit irrespective of the amount of water used seems absurd now and might need reconsideration.

But my essential point is that the water industry has to now be nationalised because it is not only failing us already but, on the basis of current plans, will probably do so forever, and that is not only not good enough, but is really dangerous to our wellbeing.

Our politicians have to now say it is time to end the shit in our water and take control of this industry to make sure that we get clean water. After all, if they cannot guarantee clean water – an absolute essential for life – what are they for?

Finally, a few technical notes. First, this analysis is based on the activities of the companies actually supplying both water and sewage services in England. It is not based on the groups of which they are members.

Second, the conclusions are based on aggregate data. They cannot be applied to any one company.

Third, the data used is extracted from databases but is correct to the best of my belief based on that limitation.

And, if you want to see the report on which this thread is based, it is here.

The report is rather more technical and much more referenced than the thread on this issue, focussing in part on the use of sustainable cost accounting to demonstrate that the English water companies are, in my opinion, environmentally insolvent, meaning that they cannot eliminate their environmental damage and remain in business.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

“I would suggest that this nationalisation should be without any compensation to shareholders.”

Shareholders are happy to accept dividends, and since we have not heard otherwise, they are happy with the business model, including the dumping of raw sewage into our rivers and waterways. That means that they take a proportion of the responsibility, and if the business is not sustainable, then they have only the business to blame.

One thing that stood out to me was the size of the dividends as compared to current equipment assets. £26 billion given away compared to £77 billion of stuff actually doing the job they are tasked with. In other words, without the profit-taking, our sewage infrastructure could have been 34% larger. (Way too simple, I know, because of depreciation and other factors, but the general feel of the numbers is depressing.)

Tok simple, I agree

But see the report

Good morning Richard.

Is it possible to ascertain to whom the interest was paid?

I ask this because it is possible that these payments, in part or in total, might be used to reduce tax liabilities, at the expense of the UK economy as a whole.

If you or I take out a loan or mortgage we will pay interest on the sum borrowed which is payable to the lender – usually a bank, which stipulates the terms of the loan.

However, large businesses who “borrow” money might do so from alternative sources: especially if the company is owned by a corporation based overseas in a “tax friendly” state.

The parent company credits the account of the subsidiary with whatever amount is required; terms are agreed for repayment of capital and interest; but those terms can be varied in such a way as to increase payments from the subsidiary to the parent organisation in order to reduce the profitability, and therefore the tax liability, of the subsidiary.

The result is that the subsidiary hovers on the brink of insolvency; the parent’s coffers swell; and billions of pounds avoid the grasp of HMRC and disappear from the UK’s economy.

I have not done that analysis, but we know much is intra-group

I understand that some of the owners of Thames Water are pension funds. And several of these pension funds are in the public sector. And I am pretty sure that these pension funds didn’t investment in water companies because they saw that these water companies were a well-run business with good prospects. They were told to investment in them by consultants.

All I see is yet more work for consultants. Who is going to do the preparatory work for nationalisation? The same consultants that keep delivering private sector failure.

Criminal, corrupt or incompetent?

Taken into temporary public ownership sounds like a good way of transfering the debt/liabilities from private to public and then handing the company back. Something which will have to happen periodically infinitely.

Pensions – Is there a hint here that employees pensions might be at risk? Everytime this issue comes up I’m surprised believing that pensions are protected.

Shareholders – Sorry but your gamble has failed, imho the state should not compensate.

Pension funds investing in water – What do we do here?

A pension fund of which I am a member is involved – the USS

My reaction has always been – what the f**k are they doing?

Precisely for that reason I have not been a member for a while.

Show me a person who can live without water, and I’ll show you their grave.

It should be blindingly obvious to those who “govern” us that clean water is a public good that cannot be innovated to the next “iphone”. You can’t add to water in any meaningful way, or re-engineer it. It is literally made up of 2 elements – Hydrogen and Oxygen. Add another element, and it is no longer water.

It is really mind-boggling that anyone seriously thinks water should be privatised. If a Government is not providing the security of clean water to it’s citizens, then what is it for?

What needs to understood is that the water industries’ part as a vital service is used by the City institutions and others to extort money from ordinary people, any solution that would cut off this revenue stream will be rejected. Sane analysis will be overridden by the political and financial vested interests who see the the coming crisis as an opportunity to extract more from government and consumers aided and abetted by a compliant media, glib PR and AstroTurf think tanks.

There are few prospects of nice high paying jobs and consultancies for the politicians and their special advisers as well as donors in a publicly owned water industry. This kind of corruption is now endemic in the UK political system.

Talk sense all you like, the money for the parasites and vested interests talks louder.

You are right….this is all about rent extraction

Hi, forgive my ignorance but I do not quite understand the following

“And the way in which water is charged for might have to change. The idea that we all pay the same price per unit irrespective of the amount of water used seems absurd now and might need reconsideration.”

In my area, water usage is metered. Previously, the charge was based on the rateable value of the property (or similar wording). Are you referring to the previous method, or are most areas not yet metered? I cannot see how you can have a system where people pay different prices per litre or whatever unit of measurement, on metered consumption.

I am suggesting that there could be a fair priced allowance per person per household and excess consumption might then need to be paid for at higher rates.

Watering the garden, washing the car and filling the swimming pool might have to come at a price, on other words.

I don’t necessarily disagree, but how would you police that? I try to be frugal with water, only wash a full load in my washing machine and dishwasher, always shower, never take a bath etc. How do you determine ‘excess consumption’?

During last summer when there was a hose pipe ban, my water company wrote to me saying because I was a ‘vulnerable person’ – I have been treated for cancer – the hose pipe ban did not apply to me. Even so, I chose not to take advantage of this generosity, although if I had nosy neighbours intent on reporting any such violations, I would probably had done so, for the pleasure of showing any inspector calling my exemption email.

It’s metered

So, a fixed amount per person at one price, and then progressive increases above that.

It really would be very easy

And yes, your situation could easily be accommodated

The Mail said this morning that Thames Water had £2.4 billion in cash to continue trading for the next 18 months, it also had £18.3 billion of debt. Could not understand this – trading on what basis, what level of service provision? What are the net equity projections?

It would appear that the company can only pass the “going concern” test if the regulator approves huge increases in the price that the company is allowed to charge for its “services”. Another meaningless statement since it is one thing to approve an enormous increase in the price charge and another thing to actually collect the necessary income, eye watering bad debt provisions would have to be made.

How could the accountancy and audit profession possibly allowed this to get to this stage?

The accounting data is way out of date…March 2023

The draft constitution in my forthcoming book “Reinventing Democracy: Improving British political governance” includes two Articles tackling this whole problem, which extends way beyond the water companies. Here is part of the explanatory footnote to Article 52:

…It requires fair treatment of all people whether as customers or suppliers and provides power to regulate new forms of financial engineering, grants nationalisation powers to the nations and (with limits) the regions, but severely restricts the price that may be paid. Tech companies now provide essential infrastructure, and their services are to be provided fairly in accordance with UK law. In nationalisations, genuine third-party debt shall be honoured, but debt acquired as part of a financial engineering scheme is to be wiped out. This protects third-party lenders, while forcing those who have extracted rents from the British public to give something back. The difficult situation of present owners not being those who undertook financial engineering (as may be the case at some water companies) is passed to the present owners, who will have to consider whether they have grounds for action against previous owners. If they bought a dud, that is their mistake. It is possible that this Article could pass some losses to pension funds, but somebody has to pay.

“Our politicians have to now say it is time to end the shit in our water and take control of this industry to make sure that we get clean water. After all, if they cannot guarantee clean water – an absolute essential for life – what are they for?”

Excellent piece, but when you say “what are they for?”; I wan’t quite sure whether you meant, the water companies, or the politicians. So I just assume that intended both – and that pretty well sums it up. The sewage is everywhere.

In the 1820s-1840s the MPs used to carry nosegays to Parliament because the air around Westminster and the Thames stank so badly. Clearly, it still does ……. for one reason or another.