Earlier this week, I published a proposed glossary entry on the true nature of our so-called national debt. This won a lot of praise, but there have been improvements to make, so I have worked on it.

I have added a summary based on what was already in it.

I have also added a whole new section because it was put to me that defining what the national debt is is only part of the answer most people want when discussing this issue. What they also want to know is why those demanding that it be repaid are wrong.

The additional section reads as follows:

Repaying the national debt

All the above having been noted, a number of refrains are commonly heard from politicians, including:

- The national debt is too high.

- National debt is squeezing out private investment, which is too low as a result.

- We are leaving a burden of debt to our grandchildren.

- The national debt is unaffordable.

- Unless we get the cost of the national debt under control we cannot afford public services.

The implication of all of these is that we would all be better off if the national debt was repaid.

None of the claims that these politicians make are true. For example:

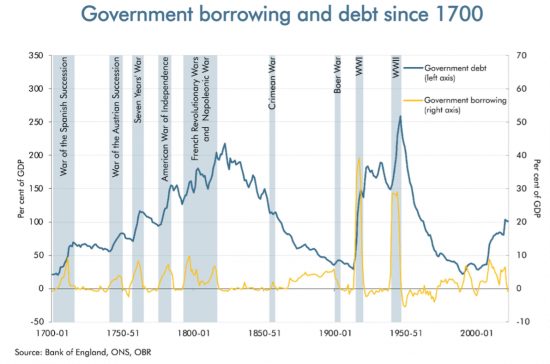

- For very long periods of time, the ratio of UK national debt to National income was much higher than it is at present and calamity did not follow. In fact, NHS, much of our social housing, and the rebuilding after the Second World War all happened when national debt was at vastly higher levels than it is now:

- There is no evidence that our national debt is in any way reducing the amount of investment in private business. Private business may not be investing enough in the UK, but that is because it cannot think of things to do with investment funds despite the fact that they were exceptionally cheap for more than a decade and has nothing to do with the size of the national debt.

- The national debt has never been repaid, as is apparent from the above chart. Our grandchildren will not repay it, any more than we have repaid the national debt created by our own grandparents. In fact, lucky grandchildren will inherit part of the national debt because it is made up of private savings accounts that form a part of private wealth. Inheriting a part of your grandparent's savings is what many grandchildren might hope for.

- The national debt is always affordable. The government can always choose to make it so in a country like the UK. If the interest rate is too high at any point in time then that is a measure of the fact that the Bank of England is setting inappropriate interest rates, and not that the national debt is too expensive.

- There is nothing about our national debt that prevents the government supplying services to people who need them in the UK. That is partly because doing so will always pay for itself if there are resources available to supply those services because they are then put to use, creating income, and so taxes paid on that income and the spending (and so further income) that it then generates. That is also because there is no known cap on the level of national debt that we should limit ourselves to. Many European countries have debt to national income levels considerably higher than that in the UK, and Japan has a national debt to income level well over double that of the UK, and all those economies are functioning perfectly well. So can we even if we increase the national debt.

Perhaps more importantly, repaying the national debt would be disastrous. It would mean that:

- The government would have to withdraw more than £1.6 trillion of money from use in the economy, which would most likely create an unprecedented financial crisis, deliver a recession, and leave businesses and households without the basic cash resources that they need to make payment to each other, not least because the banking payment system would be crippled without there being a national debt that delivers it with the money that it needs to function.

- Almost all public services would collapse because their funding would have to be withdrawn for extended periods.

- Most private pensions would collapse because they use the savings facilities that the national debt provides as the foundation for the payments that they make the most pensioners.

- The government would lose control of interest rates within the economy.

- Because of the shortage of pounds available to make payments within the economy that repayment of the national debt would create it is likely that we would have to use foreign currencies to trade in the UK, creating massive uncertainty for the whole economy. This would also make it almost impossible to run an effective tax system.

- Foreign governments and companies would have great difficulty holding sterling balances, and this would enormously harm trade in UK goods and services.

Those demanding repayment of the national debt really ought to be very careful about what they wish for. Even partial repayment or limitations on the growth in that debt could produce some of the above outcomes.

The truth is that the national debt is fundamental to the success of our economy because it provides us with our national money supply, and we cannot survive without that. Those suggesting we can either limit this so-called debt, do without it, or repay it, must be treated with suspicion. What they propose not only threatens the entire public sector of the UK, but also the economic viability of the country as a whole. It is for them to justify why they would wish to do that.

A PDF of the new version of the entry is available here. Comments are still welcome.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

There are links to this blog's glossary in the above post that explain technical terms used in it. Follow them for more explanations.

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

Buy me a coffee!

Buy me a coffee!

Thanks Richard. Good stuff as always.

Private Eye today.

https://www.private-eye.co.uk/pictures/captions/sunak-election.jpg

How do ‘The People’ of the UK ‘remove’ a failing(ed) regime?

If the tories find a ‘legitimate’ way to cancel the GE, they will.

Now we just need to correctly label as the National Wealth.

Excellent. I was looking for this just yesterday. It will be very useful.

Very good Richard

This kind of subject matter would be great for a short series of TV episodes on a big channel…

Does the national debt matter and what would happen if we repaid it?

Where does money come from?

What comprises national wealth and how can we increase it?

Who controls interest rates and are higher rates an effective way of controlling inflation?

What is the purpose of tax?

Obviously this stuff is critically important and almost universally poorly-understood. To the best of my understanding no UK political party on left or right has a coherent view on these matters.

That would be fun

But it really isn’t going to happen

Richard,

I am not sure I understand why repaying the national debt would reduce money in the economy. Say I have a gilt, which means I have paid money to the government in return for the gilt, which is then added to the “national debt”. If the government then repaid me the money by buying the gilt back, I would presumably see it in my bank account and could then spend it, or save with some non-government institution. So doesn’t the total money in the economy then stay the same?

But money is part of the national debt – right down to notes and coins

So if you repay the natyional debt you have to take that money out of exisetnce by taxing it so it no longer exists

Hence there is no state made money left

And wihout it there is no commercial mmade money either

Would it be correct to say that something like the following happens when the government buys back Mr. Kirby’s gilt for £X:

Government “borrowing” decreases by £X and Mr. Kirby sees £X in his bank account. What Mr. Kirby sees is a records the fact that the bank now owes him an extra £X and is not itself part of the “national debt”. However because of the mechanism the government uses to pay him, his bank’s CBRA has increased by £X and that is part of the national debt. In other words:

Decrease in govt. borrowing = increase in bank’s CBRA

and since these are both part of the “national debt”, it remains unchanged.

If Mr. Kirby were to withdraw his money from the bank in cash then this cash would be part of the national debt, however his bank would have had to obtain the physical cash by ” buying” it using its CBRA, and again the “national debt” remains unchanged.

Similarly when Mr. Kirby deposits money in his bank and uses it to buy government bonds these processes are reversed and again “national debt” remains unchanged.

It seems to me that the only way “national debt” can increase is for the government to spend new money and the only way it can decrease is for the government to destroy that money – e.g. through taxes, fines or fees of some sort.

The only relevance of “government borrowing” for the “national debt” is that the government may be committed to paying interest on that “borrowing”, but it is the creation of the new money needed to pay this interest and not the borrowing itself that is relevant.

As I see it, discussion of these matters is hampered by an Orwellian bank-speak whereby there is “national debt”, which is not in any normal sense debt, and “government borrowing”, which is not in any normal sense borrowing.

I think what is being highlighted is that this is not the best argument!

It’s relevant, but too complicated.

Mr Kirby,

Suppose the Government repaid all of NS&I, to take one example with practical impact at the individual, more than corporate level. What would people with NS&I savings actually do with the money?

Spend it? Punt it on shares? They could have done that instead of investing in NS&I in the first place. Why did they invest in NS&I (perhaps with a safe punt in premium bonds)? Whether they have other investments or not, the NS&I investment is a secure, protected, guaranteed investment made by the government, also offering a return (typically better than commercial banks, and safer – apart from the Government guarantee to bank depositors). NS&I is part of the final protection we all have for the security of invested savings that only the Government, as sovereign currency issuer can offer the public. It is called ‘safe asset theory’. Even if they are thoughtful about money, and possess other, riskier investments it is likely to be at least part of an individual or family’s risk diversified portfolio.

So what will happen when they have the money repaid by government, NS&I closed and a lower rate of interest in the bank account, when the receipts are, probably suddenly deposited; perhaps taking some depositors over the £85,000 Government bank guarantee threshold?

What will investors do? No doubt I will hazard, they will demand that government quickly provide an NS&I facility so they have somewhere safe to keep their money; beyond the reach of risky, improbable investments, or worse from the scams of the world.

The national debt is not altered when £100 is used to buy a £100 gilt.

A tax credit has been used to purchase an interest earning tax credit.

But the level of national debt is unchanged. Only its form has changed.

If you think form does not matter you have a point

But the claim that form does not matter is a false one

The form the debt does, of course, matter as it has consequences for the competition for resources and hence for inflation as well as for banking, insurance and individual’s ability to save etc..

However it is worth pointing out that if I borrow £1,000 my debt increases by £1,000 whereas if the government “borrows” £1,000 the “national debt” is unchanged. Most people find this quite astounding. My local MP simply refuses to believe it.

But its composition changes

Yes, the composition of the debt changes when the government “borrows”, and that is an important consideration. However the majority of the public have not got sufficient understanding to make discussion of this issue possible.

The predominant narrative has it that the national debt is the sum total of all the money the government has borrowed and not paid back, that if it gets too large the nation’s creditors may one day demand it is repaid and that most people will not have the wherewithal to pay their share. This is all nonsense but for those who believe this nonsense government borrowing can represent an existential threat and fiscal rules can seem like rational prudence.

This narrative is rarely explicitly stated but is merely presupposed by many journalists, politicians and other commentators.

Something has to be done to change this narrative. One way is to keep saying “government borrowing does not change the national debt”, something that makes no sense from the point of view of the narrative, and to be prepared to argue the point if challenged. The time to discuss the structure of the debt with someone is when he/she no longer believes this narrative.

A query… I am unsure if this is a reasonable analysis…

Is it correct that one of the key reasons there has been continued low investment in the UK economy is that returns are relatively low for the perceived risk levels and with low interest rates, and hence returns ?

Contrariwise property investments and speculation, especially at a time of QE leaking into property price spikes, have higher returns, and often lower risk. I recall a figure of 11% of QE actually reaching the ‘productive’ economy.

Banks prefer lower risk and more secure investments, so are more likely to lend on property, where there are capital growth opportunities as well as rental revenues, than, say, new industrial technology, so compounding the problem of low industrial investment etc.,

With long term imbalance in the housing market (imo initiated by Thatcher) and shortages in the private rented sector the relentless upward pressure on rents means it’s Christmas every day for the rentiers.

If this is all reasonable, it would tend to confirm Adam Smith’s utter loathing of rentiers, as the drones of the economy.

There is no investment in business because business cannot think of a need they need to meet

Specualtion is fun for them

But what we need is public investment

Meanwhile, the market is rigged for the rentiers

You’re moving in the right direction Mr Murphy, but given that the BofE now holds over 50% of issued Gilts, the national debt could be halved instantly by the Treasury and BofE doing a little book-keeping together. That would have zero impact on the economy. The Japanese Govt and BofJ should do the same and stop giving out meaningless big debt figures to be used against them by small government aficionados. And while they’re about it, dispense with the notion of independent central banks. The national debt held by the private sector consists of bits of tradeable paper (gilts). Settling this ‘debt’ before maturity, without reissue, would not mean withdrawing money from the economy but exactly the reverse i.e. so called QE on a massive scale: a financial asset swap. Not that I am suggesting that as a good idea. The government could though, stop issuing gilts or have the BofE purchase them rather than engaging in open market operations to buy them after primary sale. Over time the ‘debt’ would be reduced. Who would scream? Bond traders. Tough. It would though be a problem for private pension funds, as you point out. But it should be clear that the private pension funds are a very inefficient and inequitable means of pension delivery (and support other society damaging institutions in the form of asset management companies) and should be replaced over time by a decent state pension. As for interest rate control, we would all be a lot better off if interest rates were allowed to fall to their natural non-intervention rate, and if private banks can’t deal with that, then a state bank could.

All these issues have been addressed here many times.

It would help if you get your facts right. The APF owns about 30% of gilts.

APF

The Asset Purchase Facility (APF) houses the assets purchased by the Bank of England as part of its programme of quantitative easing initiated in 2009. The Treasury receives the profits from the APF and also indemnifies the Bank against any losses from it.

Had to google that.

It is legally a BoE subsidiary but is not consolidated because it is not under its control

Another hit straight out of the park Richard – nice work and it all makes sense to me (FWIW).

Labour keeps talking about the national finances. Truss’s budget wrecked the national finances. Labour would like to do more but is constrained in what it can do because of the poor state of the national finances that the Tories will have left. Labour must first fix the national finances before it can do anything. This is all obviously the exact same argument that Osborne made in 2010. Richard, what’s your opinion on the current state of “the national finances”?

I am sorry to say that Truss did almost nothing to the national finances and did not creaate the crisis that appeared to follow Kwarteng’s Budget

Andrew Bailey did that by announcing £80 billion of quantitative tightening the day before – which is what pushed pensiion funds into crisis and required more QE to stabilise matters.

Truss was incompetent as she should not have let Bailey do this, but Bailey was to blame.

Thanks Richard. I was going to send a copy of my latest pension statement to Liz Truss but I’ll re-address it to Andrew Bailey instead. The pension wasn’t worth much in the first place but is down more than 25% since the Truss/Kwarteng/Bailey fiasco and shows no sign of recovering. And at my age (69) it was supposed to be invested in “safe assets”. That’s a big hole in my meagre retirement plans.

@Robert Dawkins

If your portfolio is made up of safe assets such as gilts then, as interest rates decline in 2024, you will likely find that the value of your portfolio will recover most of its pre-Truss value.

You just need Bailey to follow Richard’s advice and cut interest rates!

My own opinion, for what it’s worth, is that the anouncement of £80 billion QT would have pushed pension funds into crisis had there been no budget. However it would have been reasonable to expect there would be something in the budget to compensate for it, at least in part. When it was realised that nothing of the kind was forthcoming the markets reacted.

I find it hard to believe Bailey had no idea what would be in the budget, but if he had no idea then the responsible thing to do would have been to wait until after the budget before even considering making the announcement.

Ultimate responsibility lies with Truss but her’s was a sin of omission not commission. Meanwhile the narrative that her budget caused the crisis is a nice little cover story for those who wish to promote neoliberal policies. My advice to the likes of Simon C is “Don’t fall for it!”

Bernard Hurley,

Thanks for your earlier comment of 10:57, which I found spot on.

On the other hand I can’t really agree with your latest comment.

Whilst I’m certainly no fan of Liz Truss, I agree with Richard on this, it seems harsh to blame her for not compensating for Andrew Baile’s QT announced only the day before. Even if she knew, and who knows given the BoE’s “independence”, there was no time to change the budget.

To me, the Truss débâcle merely strengthens the argument to dispense with the fictional independence of the BoE.

Great paper. Half way down page 6 do you mean to say ‘microeconomics’? Isn’t it ‘macroeconomics’ in this context?

Thanks

Noted

Apparently the paper by Reinhart, et al “Growth in a Time of Debt” supposedly found that “When gross external debt reaches 60 percent of GDP, annual growth declines by about two percent; for levels of external debt in excess of 90 percent of GDP, growth rates are roughly cut in half.”

But post-graduate student Thomas Herndon found errors in the paper, and that the opposite was true, that higher debt helped grow the economy.

Sources

Reinhart, Carmen M, and Kenneth S Rogoff. 2010. Growth in a time of debt. American Economic

Review 100, no 2: 573-578. https://dash.harvard.edu/bitstream/handle/1/11129154/Reinhart_Rogoff_Growth_in_a_Time_of_Debt_2010.pdf

Herndon, Thomas; Ash, Michael; Pollin, Robert (15 April 2013). “Does High Public Debt Consistently Stifle Economic Growth? A Critique of Reinhart and Rogoff” (PDF). Political Economy Research Institute – Working Paper Series (322) https://web.archive.org/web/20130701221358/http://www.peri.umass.edu/fileadmin/pdf/working_papers/working_papers_301-350/WP322.pdf

Well done Richard!!! Isn’t it a shame these things have been taught by elite economists and have been ignored.

Eccles made similar comments on a radio broadcast in 1939

https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/files/docs/historical/eccles/Eccles_19390123.pdf :

“Why not worry also about the burden of all of the private debts on our

children and their children, because these debts will also be passed along

to future generations who will have to pay the cost of servicing or paying

these debts just as in the case of the government debt. We should know

that all debts, both public and private, are passed along from one generation

to the next, just as all assets, both public and private, are h&nded down from

one generation to the next* It may be that Senator 3yrd would be less worried

if there were no debts, but in that case, there would be no banks, insurance

companies, or other financial institutions.”

Samuelson’s first textbook in 1948 made similar points like page 427

https://archive.org/details/economicsintrodu0000samu/page/427/mode/2up?q=grandchildren

And of course in the 80’s the great Laureate Vickrey makes your point in his first of Fifteen fatal fallacies of financial fundamentalism

https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.95.3.1340

Very good

Especially the second source

I wish there was a better term than “national debt” because it is highly misleading and is not debt in the usual sense at all.

There is

It is national savings

Or national wealth

‘There is no investment in business because business cannot think of a need they need to meet.’

This might more readily apply to big business faced with a choice of an investment producing returns for shareholders in the longer term, or doling out higher dividends and/or share buybacks in order to keep shareholders quiescent at a time when the projected returns on investment in a UK business do not meet their, often short term, ROI thresholds. Medium and smaller businesses look at investment differently in my experience, especially if the business owners have long term competitive advantage and sustainability as their key criteria for investment. The main drawback faced by medium and smaller firms is the ability to borrow on reasonable terms to invest, not so much the lack of needs they can meet. This brings me to the latest NatWest ads aimed at smaller firms. They emphasise ‘tools’, ‘resources’ and ‘business advice’, everything apart from what a smaller firm really needs, which is access to reasonable cost debt funding.

The medium to smaller business sector in the UK is crucial to productivity and investment, more so than the larger corporates.

Hence the main constraint on investment is two-fold – banks that are not remotely interested in nor expert in business growth, simply the sale of their products (e.g factoring) and also the current stupidly high rates of interest, which when the bank adds its risk premium, ends up at around 12 to 14% pa.

Agreed

I was referring to big business

Thanks, Richard. I’m going to ask a stupid question, but is “national debt” not a requirement of a growing population with more prosperity? There is obviously much more money in the world now than say 100 years ago. This money has to be created by governments/central banks, right?

So called ‘wealth creators” in private business don’t really create wealth (aside from for themselves), they just cause money to move in the economy. Business sells something, uses income to hire staff who make money and spend it. But all the money comes from the govt. Or am I mistaken?

Money is created by government and banks, but never by business except to the extent that it borrows

Core money is created by government, always. I have noted on this coming soon.

My understanding is that banks can create money as loans that need repaying with interest. The money paid back is deleted, so it’s temporary.

The government can spend new money into the economy, and that which is not taxed back, contributes towards the “national debt”. A certain level of national debt is required for the economy to function, and it has to be spread evenly so that those who need it, can use it. Money in the economy can be taxed back (and deleted), and helps control inflation.

I guess credit cards are a way that people can also create money, temporarily, that also needs paying back.

I would also argue that people are the wealth creators, not businesses which just move money around.