Regular commentator on this blog, Clive Parry, has written a note on how the banking system and government and commercial bank money creation work, which I have published this morning.

Let me be clear: I agree with everything that Clive has said until he reaches his discussion of the consequences of money creation on the banking system. That is in paragraph 3(3). Even then, I do not dispute what he says about what those consequences that are within the construct of current regulation, and from paragraph 6, our thinking merges again. What I am disputing is not what those familiar with the banking, finance and bond trading systems suggest it is but what it should be.

I am aware that it could be said as a result that I am defying the logic of David Hume when doing so. I am seeking to develop an ‘ought' from an ‘is'. I would disagree. My suggestion is that if the facts are themselves a reflection of ethical judgement then we can most certainly develop them from what is into what ought to be.

And I am saying we have much about the banking system wrong. That should not be a particularly difficult suggestion to make. If a great many people, including in all likelihood the majority of bankers, think that banks are intermediaries between savers and borrowers, when we know that is not the case, it would not be surprising if a system of regulation created before that was widely recognised is also inappropriate, and wrong. In summary, I am saying that the Basel capital requirement regulations used by banking throughout most of the world are bound to be wrong because they are premised on a misconception of the ultimate source of money creation, which is now base money created by direct government funding of their economies.

What Clive makes clear in his comments, is that banks are forced to lend to each other if their central bank reserve account balances move out of line as a consequence of interbank payments. This is because banks are not permitted to make long-term loans that are funded by what are, in effect, overnight loans from their central banker, which is what central bank reserve accounts are deemed to be because this was their nature prior to the 2008 global financial crisis, when the balance is held upon them were, in current terms, insignificant.

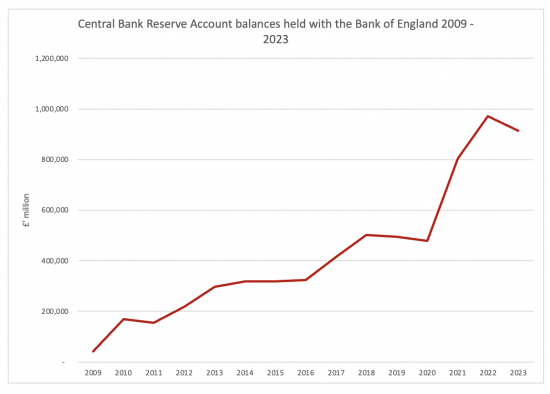

Prior to 2008, the Bank of England what is seen as a lender of last resort to banks. As a result, central bank reserve account balances were frequently less than £30 billion in aggregate. As a consequence, they were an insignificant asset on the balance sheet of all the UK's clearing banks, with similar situations arising in banks around the world. Since then, this has happened in the UK, with this situation broadly being replicated worldwide:

Far from being insignificant sources of funding, central bank reserve accounts held by banks with their central banker are now major assets of most major banks. This is not the result of QE, I stress (because that is a sham): it is the result of government deficit funding of its spending financed by the Bank of England.

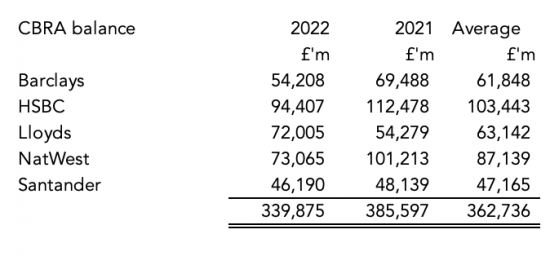

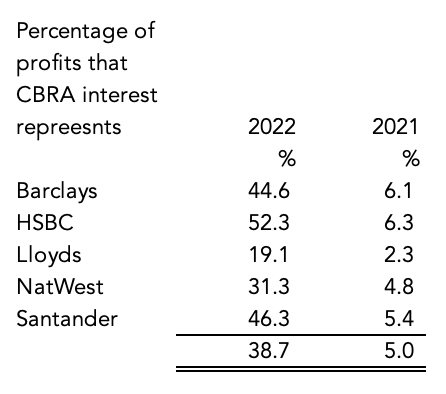

I looked at this issue in August last year, when I reviewed the impact of central bank reserve accounts on the balance sheets of the UK's five largest retail banks (Barclays, HSBC, Lloyds, NatWest, Santander). As I noted then, the existence of central bank reserve account balances in the sums that are now in use has had a profound impact on their operations. Take this table, which shows the scale of the central bank reserve account balances held by these banks:

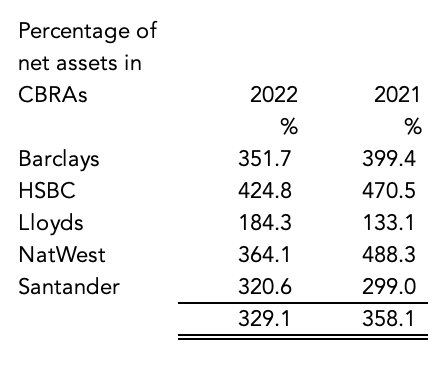

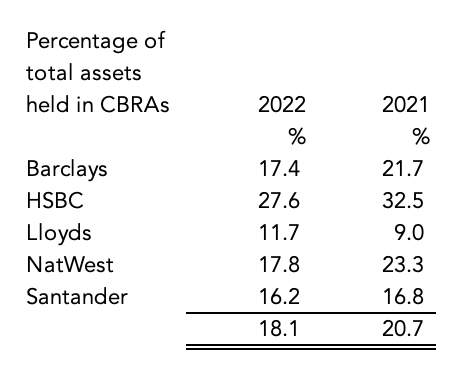

To give an indication of the significance of these sums note these tables:

These are massive changes from the era when central bank reserve accounts were insignificant. The balance sheets of these banks now make no sense without considering the central bank reserve account balances.

These are massive changes from the era when central bank reserve accounts were insignificant. The balance sheets of these banks now make no sense without considering the central bank reserve account balances.

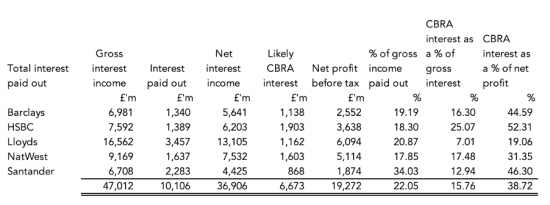

There has also been a massive impact on profit:

To put that in context, note this data for 2022:

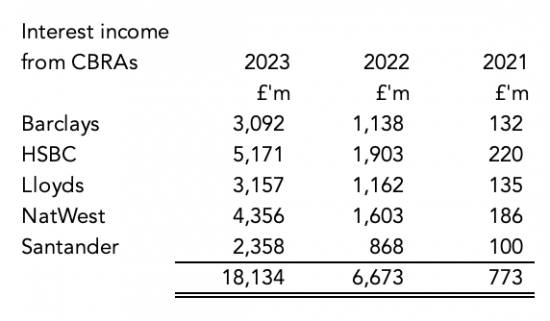

CBRA interest averaged 38.7% of profit, but also covered more than 65% of interest paid to customers in 2022. The scale of the change was also staggering: this is the 2023 data on interest earned:

All of this, supposedly, is not happening in the world Clive Parry describes where it is assumed that banks cannot rely on overnight funding from their central bank when it makes up an average of 18.1% of their net assets in 2022. That is ludicrous. It is pretending the world as it is does not exist.

So, why is that? I suggest that there are four reasons:

- It's too hard to change Basel. Regulatory inertia is requiring that the pretence that the world is as it was and not as it is must be maintained.

- Basel does not understand that banks are not intermediaries. It would seem very likely that this is the case.

- It suits banks to pretend that QE will be unwound when we know that the process of doing so–called quantitative tightening – which is being pursued by the Bank of England right now has nothing to do with QE but is instead a policy to keep interest rates artificially high in a wholly destructive fashion that does, however, suit the bank agenda of upward redistribution of income.

- It denies the reality that banks really do not exist independently of each other, they cannot be regulated in isolation, and none of them are too big to fail, meaning that the pretence implicit in Basel that they are not too big to fail can be maintained. We know that this is nonsense.

Of these, the last is, to me, the most important. The reason why banks are not allowed to fund themselves using overnight funds from central banks is not because this is not possible (it always has been), and nor is that because this should be seen as a last resort, which given the existence of central bank reserve account balances is clearly not the case, but because the pretence is being maintained that the banks must regulate each other through their interbank lending. This is the supposed indicator of stress to which the central banks want to look.

That, however, makes no sense. When the banking system as a whole is now utterly dependent upon the availability of central bank funding to maintain its liquidity, as the Truss debacle proved amongst other things, then to pretend that reliance on interbank lending is the indicator of bank stress is simply wrong. In the current environment, what a central bank needs to know is the degree of dependence that a bank has on its central bank borrowing to fund this activity, and this is where stress would be best measured. In that case, the current regulatory environment that creates the funding situation that Clive accurately describes, is counter-productive. When it is the action of a single bank that can threaten the system as a whole, what a central bank like the Bank of England needs to know is whether one bank is advancing funds in a fashion out of step with the action of other banks, which would clearly be indicated by its central bank reserve account falling disproportionately, which fact could be hidden by interbank lending. It would, therefore, I suggest make much more sense to regulate via the CBRA's, rather than to deny their use for this purpose. This would also save much of that, I suggest pointless, activity in Treasury functions to which Clive refers. But most importantly, systemic risk would become more apparent more quickly, and that seems to me to be key.

Have I got something wrong, or am I simply refusing to think as bankers want me to do?

Finally, my thanks to Clive: he made me think in more depth about this issue.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

The standout for me was the dependence of banks’ profitability on interest payouts from the BoE. Given gov’ ownership of the BoE, this starts to look like socialism (gov largesse) for banking (pass another bottle of Bolly would old chap) and given current gov’ funding developments, gruel for UK serfs.

Observation: I was able to follow, just. Those less expert would not follow and would be unable to get all the implications. This is not a criticism per se – but rather leading to a question: how to take it and turn it into a narrative that “the person in the street” could understand.

Agreed, although I admit my focus right now is how to take all guys and turn it into academic journal papers.

Any editors want to follow up on Mike’s suggestion?

“The standout for me was the dependence of banks’ profitability on interest payouts from the BoE”.

Spot on!

I hope my piece also made this point….. but you have done it better!!

Good questions, Richard? Well, I thought perhaps so; but note that nobody else here has cared to pick them up, answer or rebut them.

I have been working on a much longer summary, if only to sate my own curiosity, this afternoon. It may be up tomorrow,mid I get time to edit it this evening. Blogging is a 15 hour a day activity right now, it seems.

I understand. I am glad we have had the blogs and open discussion; it has provided some illumination. Nevertheless, I still see some well informed, but frankly closed mind thinking; an assumption that the current model is sufficiently robust. Standing on the outside, I am not convinced. The test, as Clive knows – because he says it often enough, is ‘unintended consequences’, and these are only typically noticed in a crisis. LDI was a crisis; and both a close call, and costly. That money was blown. The ‘accidents’ are happening more often in a digital world the bankers do not really understand, and a financial world of characters who will think up devices to make debt look like equity, or whatever to stay on step ahead of the regulator (and they move faster, and count in nanoseconds); and the small effects are like aftershocks, or are the pottens of the next financial earthquake?

Shadow banking, which has not been sufficiently regulated, notably since 2008 (as an outsider I suspect the authorities do not have a clue what to do, as they look at their crude arsenal of rate and regulator ‘bows and arrows’ in the digital age – or even of adequate knowledge among bankers – that will work) and remains an unresolved issue. Regulation has an appalling record of total systemic failure in the financial and all sectors in the history of (not least modern) British government; and that is an indisputable fact. The evidence of unassailable complacency, delusion, incompetence, total failure, and even of whitewashing, is hard to resist.

This is not a world open to science or logic. Indeed, as Minsky realised the whole financial system is unstable, and the authorities are using fairly crude procedures to keep it from falling over; and it does fall over; and inevitably will do so again. Every time it falls over it causes severe penalties for everyone (2008 is still with us, and we are still paying for it, one way or another); often compounded by the deep ignorance of bankers of their own subject. Yet at great cost they construct a new, supossedly better variant of their unreliable model (until next time); pat themselves on the back for their profound wisdom, and carry on as if nothing has happened.

Sometimes the best perspective is found, standing well outside the model you are examining (and too far to hear the ex-post rationalisation for the rickety structure that the world actually experiences)

That is what I will be trying to do with my post tomorrow

“are the portents… ?” I honestly thought I had corrected that. Are you using Horizon software, Richard?

I did not edit it John…..

Eh, Horizon? It was a leaden joke, Richard!

I know, it must be hectic.

Very, right now

From about two minutes after waking up until I declare enough (soon) for the day

We agree on a few things

Certainly that the “windfall” interest payments on CBRA balances are at a level that dwarfs any “fair” compensation for running free current accounts/payments/branches etc.. We need a way to reduce these payments but still maintain monetary transmission of policy rates to the real economy. This is tricky but, in my view, not impossible.

I think you also get my point about the lending business needing to be funded by something other than overnight interbank lending – well, at least under current Liquidity rules….

… but you then challenge whether these rules are needed given the huge balances that exist in CBRAs. (Correct me if I have got the wrong end of the stick, here).

I think they are still needed – indeed, they might even need tightening. With SVB (and Credit Suisse to some degree) we see that modern technology means that bank runs happen FAST. We have known for a long while that interbank lending to a “wounded” bank dries up quickly – in minutes, literally. And the changes in Liquidity rules after 2008 reflected this fact … but we now see that the assumptions about “stickiness” of retail deposits is too generous, too. You suggest that banks can always borrow from the Central Bank but this only true up to the level of eligible collateral that it can pledge.

In theory and in practice the a high level of aggregate Reserves does not deliver banking stability…. the Liquidity Rules are essential to reduce (but not eliminate) the risks of an individual bank’s failure and, when a bank does fail, prevent contagion to other sound banks.

You suggest that monitoring the CBRA balance for a particular bank might be a better way to regulate. Certainly a sharp drop in the balance is a red flag…. but it might only give you a few hours warning. It also does nothing about contagion.

These rules certainly raise the cost of credit to the real economy (as “cost of funds” is clearly a key input for loan pricing) but this cost is not profit for the banking sector – rather it is trousered by investors that buy bank bonds – who are (almost) exclusively non-banks (Pension funds, insurers, etc.). If the cost of credit is too high then the answer is to cut the policy rate, NOT cut the cost of funds relative to the policy rate.

So, by and large, I think the framework we have is OK. Continual refinement is always required in the light of experience but I really do think there have been great advances since 2008 in making a safer banking system.

I think we actually agree on quite a lot of things.

My question is this – given contagion is so rapid – which is what is the best communication method? I am suggesting that CBRAs could deliver that. What else might? I think that is a key question.

Just to clarify the Liquidity Rules issue here, if I amy; I understand the BoE was calling for a buffer of 50% to 60% of funds in assets that can be liquidated within seven days; an increase from 30%.

The context of these rule changes isn’t, as I understand it the banks being discussed here by Richard, at least directly but Shadow Banking and Hedge Funds; at least the FT discussion of the increase in liquidity buffers brought the two issues together in conjunction in the same article; which raises the question what solution is the central bank using to address precisely what problem?

.

If I may develop this a little, in an attempt to stand back as an outsider and make some sense out of it all; if on average the British major banks have a total of £340Bn of CBRAs on their balance sheets, representing a mean 329% of net assets, and CBRA interest representing a total £18Bn, and an average 39% of profits; these balance sheets no longer look like a commercial bank sector.

It looks more like central banking, with small commercial banks attached. If the problem is shadow banking, is this the best way to tackle it?

Good questions

The basic rule is that banks need to stay alive and meet all payments due without access to interbank borrowing for 30 days. There are certain assumptions about what outflows a bank will experience when under stress. On one end of the spectrum, small retail deposits covered by a government guarantee are assumed largely to stay with the bank (this is important as it means that small retail savers ARE important to banks); at the other end, interbank lenders will pull their money immediately.

The only way banks can do this is to fund for longer terms… and this has, in practice, got to be from non-banks.

Can we resume this tomorrow?

But might I ask, who are you saying provides that non-bank funding?

Well, for tomorrow?

1. Retail deposits are important. Noted, but notice, as they are covered by a government guarantee; at £85,000 a ‘pop’ that is a big Government contingent liability hanging out there; in addition to supplying almost 40% of bank profits from CBRA interest.

2. If small bank deposits are Government guarantees to the depositor, not the bank (I have mentioned them here often enough); why are they “assumed” to stay with the banks in the liquidity rules? Since they are guaranteed, from the bank’s perspective their assumption must be, that however used (as collateral?) this is not ultimately borrowing that is at risk, for them.

The point that you seem to keep ignoring is that payment of interest on reserves has been found to be required for central banks to transmit monetary policy into the real world. It is not just the Bank of England, but the other major central banks that do it too. The New York branch of the Federal Reserve makes very clear on its website why it pays interest on reserves.

Extract from: https://www.newyorkfed.org/markets/ior_faq.html

—————–

How will authority to pay interest on reserves be helpful in implementing monetary policy?

The Open Market Trading Desk (Desk) at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York is authorized to arrange open market operations in accordance with the operating directive of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), which sets a target for the federal funds rate. Without authority to pay interest on reserves, from time to time the Desk has been unable to prevent the federal funds rate from falling to very low levels. With the payment of interest on excess balances, market participants will have little incentive for arranging federal funds transactions at rates below the rate paid on excess. By helping set a floor on market rates in this way, payment of interest on excess balances will enhance the Desk’s ability to keep the federal funds rate around the target for the federal funds rate.

Why is the payment of interest on reserve balances, and on excess balances in particular, especially important under current conditions?

Recently the Desk has encountered difficulty achieving the operating target for the federal funds rate set by the FOMC, because the expansion of the Federal Reserve’s various liquidity facilities has caused a large increase in excess balances. The expansion of excess reserves in turn has placed extraordinary downward pressure on the overnight federal funds rate. Paying interest on excess reserves will better enable the Desk to achieve the target for the federal funds rate, even if further use of Federal Reserve liquidity facilities, such as the recently announced increases in the amounts being offered through the Term Auction Facility, results in higher levels of excess balances.

—————–

It’s terribly convenient to think so

Now, let’s make clear £600 billion is not reserves but state equity capital with no return due. Will the remains balance be sufficient to deliver monetary policy? Clearly yes. So, politely, stop your nonsense.

I certainly am not ignoring this.

A crude approach would be to say “Barclays, HSBC, Lloyds and Santander – you are central to UK banking and payments; you must each keep £30bn in your CBRA and this will unremunerated”.

This would cut the interest paid on aggregate reserves by a decent chunk and policy rates would still get through to the real economy.

Now, that is a bit arbitrary so would need refinement – but I think you get the picture.

I do

I would refine it – but am working on this

Clive,

I would agree that there is no need to pay interest on ALL reserves, particularly not the mandatory minimum reserves balances. This is the policy of the European Central Bank after all. But given that current reserves are much higher than the minimum, it sounds like what you are suggesting is for banks to be required to hold a much higher level of minimum reserves than is currently the case.

The Bank of England has recently done its own research into what the commercial banks themselves would consider to be the minimum demand for reserves that they would be comfortable holding before taking action. The answer was about 325 – 400 billion GBP, or around 50% of the current reserves balances in aggregate. Source: https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/bank-overground/2023/what-do-we-know-about-the-demand-for-bank-of-england-reserves

So you are saying no reserves on that sum? It would be a start

Thank you, Rupert, I knew I had read something about this….. but couldn’t remember where.

I do think the BoE produces interesting research both “overground” and “underground”… I just wish that senior management read it!

That number seems reasonable. “Back in the day” this might have seemed too high… but having stared into the abyss in 2008 I do think that banks are far more cautious with respect to liquidity and reserve balances. Having said that, 2008 is a while ago and the lessons are rapidly being forgotten.

So, it might be reasonable to start with (say) £200-300bn to be unremunerated… but we are still left with the issue of distributing it around the banks in a fair way. Someone (and it is beyond my skills) needs to create an algorithm that blends balance sheet size, payments volume (and a few other variables, no doubt) to deliver “a number” for each bank.

Of course, banks would whinge but I do think they would be wise enter this debate constructively before politicians start baying for blood. It is only a matter of time before journos lead with “we give more to the banks than we spend on our soldiers” and there is one way that ends – harsher, ill thought out solutions.

I will be doing the numbers as soon as bank accounts are out….

I would also add that, on a technical note, there is considerable difficulty in deciding what open market operations are required at any point in time and the Fed has got it wrong on a few occasions. Forecasting the desire to hold Reserve balances instead of UST collateral by banks and at what price differential is a learning curve in this world of high rates and excess reserves.

Nonetheless, there is no imperative to pay interest on ALL reserves.

We are agreeing – we now need to define where…..

My understanding fails completely at the % of net assets in CBRAs. when the figures are way over 100%.

I am a lay person with no formal economics or banking training, but if you are hoping to translate it so that us non techs can understand that would be a helpful starting point.

Net assets represent the total sum shareholders gave invested in a company, so the CBRAs are many times that is what I am saying.

‘interest income from CBRA’s’ = astonishing.

Free money for bankers!

Richard

As to watching dramatic changes in reserve balances of banks it is certainly a fine idea.

However it seems to me that. It is would not be out of the unusual for banks to be creative at escaping scrutiny on this as they do on other regulations, especially in times of crisis when it often pays any failing bank to resort to creative accounting to fool the regulator, if not committing outright fraud.

One such example I recall was Anglo Irish bank in Ireland. When the bank borrowed billions of Euros on the last day of the financial year from another large Irish bank on a one day repo. They then presented this a “new “investment from a client to cover their huge losses, returned the money the next day and avoided any alarm from the Irish regulator for several crucial months. The regulator did actually query this suspicious activity at the time but was all too easily fobbed off by the bank hierarchy. As you have pointed out, bank runs happen in days, we don’t usually get months notice of these issues.

A second example was with Barclays finding a “miraculous” circa £11 bn investment from the Qatari Sovereign wealth find after 2008 , which avoided them having to be rescued by the state like most of the other high street banks. Something they have been through the courts for and fined by the FCA. Though the ensuing courts cases failed to nail any direct offense, I believe it was mainly down to a case of expensive lawyers and accountants muddying the waters. Though a £50 million fine suggests all was not strictly bona fide. End result is they got away with avoiding the huge embarrassment of being nationalised at relatively low cost.

https://www.thisismoney.co.uk/money/article-11340309/Barclays-fined-50m-Qatari-fundraising-2008-crisis.html

The banks are very adept at skirting round all regulations in a tight spot and also then spend much time and money in calmer times lobbying to water down the ones that are in place.

We do need to do something better than what we currently have, your suggestion here is another possible answer, but we would also need to beef up the regulatory bodies, much as you suggest that HMRC needs beefing up.

Richard,

The extraordinary profits from interest on CBRAs is for me, your most important point. Presumably the intent of QE was for the benefit of the people on bank shareholders! What would happen if Covid was in a 5 year period followed by a massive earthquake in the UK, followed by a massive tidal wave, followed by a massive oceans volcano, followed by another epidemic, followed by a war – sorry there is no money??

It seems to me that the preferred approach was in a tribute to a deceased progressive economist, by progressive economists who said this about the deceased’s views

“The Central Bank should supply money for public investment at zero interest, so that the State can directly allow the production of real social wealth out of publicly-owned institutions.”

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09538259.2022.2076349

To address the absurd situation on profits for CBRAs I propose the CB issue digital cash and coins. The CB would not be involved in accounts or retail banking at that point. They would just issue a digital version of what they already issue – banknotes and coins. They could use those coins to buy government debt from the government directly or even the banks in QE. It would be like driving an armoured car over with a load of cash. The government could write checks on that. In QE the banks would receive money that would shrink their balance sheet, rather than accumulate reserves. No interest – it solves the absurd interest on CBRAs.

I can see no way that cash and coin are going tio be use to buy government debt

How do you propose that?

And what is the questiion that answers?

Readers may find the following document of interest:

The self-financing state: An institutional analysis of government expenditure, revenue collection and debt issuance operations in the United Kingdom

UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose (IIPP) Working Paper Series: IIPP WP 2022/08

https://www.ucl.ac.uk/bartlett/public-purpose/publications/2022/may/self-financing-state-institutional-analysis

Abstract

This paper constitutes a first detailed institutional analysis of the UK Government’s expenditure, revenue collection and debt issuance processes. We find, first, that the UK Government creates new money and purchasing power when it undertakes expenditure, rather than spending being financed by taxation from, or debt issuance to, the private sector. The spending process is initiated by the government drawing on a sovereign line of credit from the core legal and accounting structure known as the Consolidated Fund (CF). Under directions from the UK finance ministry, the Bank of England debits the CF’s account at the Bank and credits other accounts at the Bank held by government entities; a practice mandated in law. This creates new public deposits which are used to settle spending by government departments into the economy via the commercial banking sector. Parliament, rather than the Treasury or central bank, is the sole authority under which expenditures from the Consolidated Fund arise. Revenue collection, including taxation, involves the reverse process, crediting the CF’s account at the Bank. With regard to debt issuance, under the current conditions of excess reserve liquidity, the function of debt issuance is best understood as a way of providing safe assets and a reliable source of collateral to the non-bank private sector, insofar as these are not withdrawn by the state via quantitative easing by the Bank of England. The findings support neo-chartalist accounts of the workings of sovereign currency-issuing nations and provide additional institutional detail regarding the apex of the monetary hierarchy in the UK case. The findings also suggest recent debates in the UK around monetary financing and central bank independence need to be reconsidered given the central role of the Consolidated Fund.

Richard … to “I can see no way that cash and coin are going tio be use to buy government debt”

That is the premise of MMT. The only CB money the non banks can use is cash and coins.

FED vp Andolfatto addresses the MMT money issuer line with this caveat “When the interest comes due, it can be paid in legal tender—that is, by printing additional U.S. or Federal Reserve Notes. It follows that a technical default can only occur if the government permits it.”

https://www.stlouisfed.org/publications/regional-economist/fourth-quarter-2020/does-national-debt-matter

Maybe.

But let’s recognise the immateriality of notes and coins, meaning that the observation as to their use has little practical meaning.

Right – little practical use as I used to tell my students. Imagine the size of bank vaults, imagine all the transfer of bills, imagine all the criminal activity.

But digital bank notes solves all those problems. Instead of 3% of the money supply being cash and coin and 97% being bank credit, things could change significantly. If the CB did QE with cash there were be no interest for CBRAs. The swap would be for bank notes, not settlement balances. The cash would sit in bank vaults and be a loanable asset. The commercial bank balance sheets would have shrunk when they sold the bonds. With digital bank notes the same dynamic takes place. The cb holds the bonds, passes interest back to the government, and the bank will lend to the private sector with no interest collecting CB settlement balances on their balance sheet.

Sorry Joe, but I think this is a waste of my time.

Every one of those notes would be banked. Nothing you are acting makes any sense, ant all. I am closing discussion on this as it is a fantasy of no meaningful value, in my opinion. People quite emphatically will not want your notes.

Fair enough Richard – it is your blog 🙂 And an excellent one to follow! Let me ask a question rather than propose big changes, a question a lot of people need help on:

Richard you responded to Tim Kent in the last few days about the BoE 97% money statement … being bank money. You said “NO! That is pre 2008 data and simply wrong. Around 40% of money is now govermment ceated and around 60% commercial bank”

I checked out your glossary entry on money creation https://www.taxresearch.org.uk/Blog/glossary/M/#money-creation. You reference the Bank of England 2014 paper https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/quarterly-bulletin/2014/money-creation-in-the-modern-economy.pdf It says “Those banks can use them to make payments to each other, but they cannot ‘lend’ them on to consumers in the economy, who do not hold reserves accounts.” That statement means to me that only 3% of the money supply is government money abecause the 3% is cash and coins – The public can’t spend central digital bank money. The 2014 papers says that as did Andolfatto of the Fed and every central bank I have read. If I am wrong, then all the curious trying to get it right need help from you.

Base money is considered to be money , as much as commercial money is, as it is used for inter bank settlement, which is a vital transaction.

Joe,

You have to remember that the 3% cash and coins vs the 97 % electronic money came from an era when the banks held very little reserves because there were not many reserves in the system then, most of the money supply prior to 2009 was bank deposits.

This actually worsened the 2008 financial crisis as banks couldn’t get hold of enough reserves via the interbank markets. So QE came along to sort that out. It did, but it has meant that the proportion of bank deposits vs state issued reserves has rather dramatically changed, the Covid round of QE added even more state issued reserves in 2020. Though it isn’t cash and coins we can all use, it is still much more central bank reserve money in existance. Just it is sitting idle in bank accounts. Something Richard is intent in putting to better use. Not to mention stopping interest being paid on it!

Well said Vince. Still the larger measures of money do not include reserves … M1 M2 in table 1 of 2014 BoE paper on money.

Joe,

As to money measures, well they have had a variable history, it is hard to know what they are actually trying to measure, as you say there are M0,M1, M2 etc etc and it has changed over time.

These new reserves are not shown in the usual M system for sure , but they are still there lurking beneath the surface. In this case it is probably true that actual notes and coins are an even in smaller use as Covid finally seems to have done for them. It all depends on what types of money you are comparing I guess.