Many organisations on the left of UK politics are now calling for wealth taxes. The Taxing Wealth Report 2024 does not do so. It is appropriate to explain why that is the case.

As the Taxing Wealth Report 2024 has shown, because of the disparity between the tax rates applied to income and increases in wealth arising in each year it is possible that an additional capacity to tax of up to £170 billion per annum might be available in the UK. However, just because a potential tax base exists does not mean that it should be taxed. Nor does it mean that the tax base in question must be taxed in only one way.

It is my suggestion that it would not be wise or appropriate to introduce a wealth tax in the UK at this point in time. There are a number of reasons for saying so.

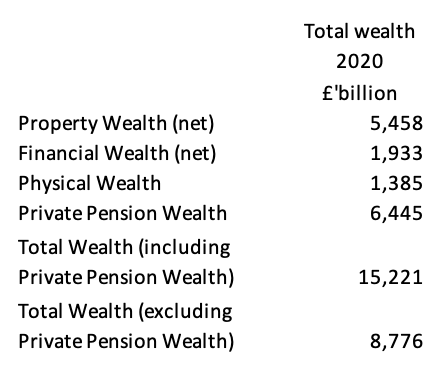

Firstly, whilst it is reported that there was personal wealth exceeding £15 trillion in the UK at the time that the last estimate was prepared in 2020 it is quite clear that a significant part of this might be unavailable as the basis for a wealth tax. The breakdown at that time was as follows:

Much of the UK's property wealth is tied up in private housing and there would be considerable political resistance to imposing a wealth tax charge on people's home, as past evidence has indicated. Whilst it is undeniable that some of that wealth is also second homes, buy-to-let property portfolios, commercial property, and land used for commercial and non-commercial purposes, and all of these might logically be within the basis for a wealth tax, this does not eliminate all the problems of imposing such a charge. There may well, in fact, be considerable difficulty in doing so, because of:

- Establishing who owns a property, since by no means all land and buildings are registered within the UK.

- Valuing these properties when those valuations might be deeply subjective in many cases, and therefore open to considerable (and costly) dispute.

- Establishing a basis for re-evaluation of property values on a recurring basis to ensure that a tax remained relevant. In this context, it should be noted that property valuations for the purposes of Council Tax in England have not been updated since 1992, precisely because of this difficulty.

It would be a brave government that took on these issues. To do so, thinking that the basis for a wealth tax on property could be established within the lifetime of a single parliament, would be wildly optimistic.

Property is not the only area where such difficulties might arise. For example, whilst most physical property would fall outside the scope of a wealth tax because it comprises household effects and things such as cars, there are inevitable exceptions to this rule, including valuable collections, works of art, and so on, all of which could, in theory, be subject to wealth taxation. However, once again, establishing a basis for taxation for such assets and updating it on a regular basis would be exceptionally difficult.

The same problem is to be found with regard to financial wealth. Of the total sum of such wealth noted, it is very unlikely that any government would be willing to impose a wealth tax charge on savings in pension funds. Included in the sum of £1.9 trillion of financial wealth outside such funds is at least £600 billion saved in ISA accounts. It is, again, unlikely that any government would be willing to impose a wealth tax charge on these texts incentivised accounts. This leaves approximately £1.3 trillion of other financial wealth but by no means all of this will be saved in readily marketable assets. Some will, for example, be tied up in the value of private companies and businesses. These are notoriously difficult to value with such valuation exercises often being the subject of protected negotiation and dispute between taxpayers and HM Revenue and Customs, which the imposition of a wealth tax would only make it worse.

Taking all these factors into account it has to, firstly, be concluded that the potential basis for a wealth tax charge is much lower than the total financial wealth of people resident in the UK.

Secondly, it should be apparent that providing an adequate legislative base for such a tax charge would be extremely difficult without creating significant opportunities for loopholes to be exploited.

Thirdly, taking into consideration the need for consultations on all stages of this process, the time required to create such a tax would be considerable.

Fourthly, even if all these processes could be concluded, there would then be a considerable cost to administering this tax because of the inevitable high level of disputes that would arise as to the basis of charge to be made. The fact that those subject to this tax would also, most likely, have the means to engage accountants and lawyers to assist them in pursuing these disputes only increases the likely potential cost of collecting any tax owing.

For all these reasons, it is inappropriate for practical reasons to impose a wealth tax in the UK however appealing such an idea might be when considering the gross inequalities that exist within the country and the apparent disparities in tax paid that we note do arise on a persistent basis.

This does not, however, mean that there are no available taxation solutions to tackling the issues that the Taxing Wealth Report 2024 has noted arise as a consequence of the disparity between the tax rates now paid on income arising during a period and the average increase in wealth of UK households accruing during the same period. What that report suggests in place of a wealth tax are a wide range of reforms to existing taxes payable either on high levels of income, or upon income arising from wealth, or on the enjoyment of certain types of wealth. The breadth of these reforms is potentially quite significant, and include:

- Aligning capital gains tax and income tax rates.

- Reducing the capital gains tax annual allowance.

- Abolishing entrepreneur's relief in capital gains tax.

- Reforming inheritance tax.

- Pensions

- Business property

- Agricultural property

- Charities

- Houses

- Rates

- Reforming rates of income tax.

- Reforming national insurance charges on higher levels of earned income.

- Creating an investment income surcharge on unearned incomes.

- Restricting pension tax reliefs to the basic rate of income tax.

- Abolishing higher rate tax relief on gifts to charities.

- Abolishing the domicile rule.

- Reforming VAT to change tax rates on:

- Private school fees

- Financial advice

- Creating close company corporation tax rules.

- Companies House reform

- Reforming corporation tax admin

- Recreating large and small company corporation tax rates.

- Capping total ISA contributions.

- Council tax reform, including:

- Higher rates of tax for high-value properties

- Additional rates of tax on second and subsequent properties

- Additional taxes on vacant properties.

These reforms are of varying complexity. Some, such as the alignment of income tax and capital gains tax rates, would be easy to implement and have historical precedent. This is also true for investment income surcharges and close company rules for corporation tax, for both of which there are precedents that create significant knowledge bases that would assist the recreation of these charges. In the case of all the potential reforms of this type the creation of new charges should be a relatively straightforward matter, capable of implementation without significant time delays or the creation of substantial taxation disputes. This is the common characteristic to almost all these proposals: they are easy to deliver.

Importantly, however, because of the wide range of options available, it is obvious that not all these changes need to be implemented at the same time, and a rolling programme of reform could, instead, be undertaken. Critically, this suggests that the net outcome of this programme of reform would be significantly more successful than any attempt to impose a single wealth tax.

I offer an analogy by way of explanation. As any golfer knows, setting out to play a round of golf with just one club, whatever it might be, would result in a disastrous score. Golfers take a wide range of clubs because when doing so they have the range of tools necessary to address the wide range of scenarios that they will face whilst completing a game. I suggest that having a single wealth tax would be equivalent to playing a round of golf with, for example, a putter. Having the range of tax reforms proposed in the Taxing Wealth Report 2024 might instead be the equivalent to setting off with fourteen clubs in the golfer's bag, which considerably increases the chance of achieving a good score. So it is with taxation. Having a wide ranges of taxes imposed at relatively low rates on relatively easy to identify tax bases is likely to produce an overall taxation yield greater than a single tax on a peculiar tax base might ever achieve. It is on the basis of this logic that the Taxing Wealth Report 2024 has been written. Reforming existing taxes can achieve so much more than a wealth tax might.

A summary of the proposals made in the Taxing Wealth Report 2024 is available here.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

Why is nobody taking any notice of your work?

They are

what coverage have you had? outside of your blog i haven’t seen anything?

Maybe that’s because you’ve been too busy changing your name here. At least five identities so far. It must be hard for you to keep up.

“Abolishing higher rate tax relief on gifts to charities”.

In some cases charities are, de facto more effective and flexible in providing help in their chosen area of expertise than the cumbersome bureaucracy of official channels; and possess more informed knowledge about how some difficult, specific social problems arise, and how to distribute help best to those who need it. Indeed, I suspect Government should use charities knowledge of their communities and area of expertise more, in the execution of policy. I am therefore not at all convinced by this proposal.

I assume the reference to “charity” is to genuine charities. If there are charities which do not seem very ‘charitable’; there are other methods than this to fix the problem.

I am not proposing an end to tax relief on gifts.

I am just suggesting an end to the scheme where higher rate taxpayers benefit from the gifts and charities do not.

I was thinking of the fact that it may be the tax benefits for higher rate payers that encourages them to make payments to charities (sometimes substantial – they can afford it). The problem is not that the tax benefit itself does not accrue to the charity; but the risk of a disincentive for the higher rate tax payer to gift the payment to the charity because of the net cost to them; it is not the morality of giving alone that drives the success of the charity sector.

The evidemnce from HMRC is:

a) They do not pay more

b) Most do not kn ow about the releif

c) Proprtionately the less well off give more

So, no evidence that this releif works in other words

I do not wish to persist at length, but I do not think I was claiming they pay more (on average, in total?); I have no evidence to ground such an opinion; I am simply saying that given higher rate payers have a 40% tax benefit, I am not sure they would give as much as they currently do gift, if that tax benefit was cut in half. That is all; but it is still a penalty for the receiving charities.

I am solely thinking in terms of outcomes.

My point is that HMRC research shows that is not the case

I just do not understand how HMRC could know what higher rate tax payers would have gifted, if the tax had been 20%; when the tax is 40%. What a higher rate tax payer gifts is not dependent on what 20% taxpayers gift; every taxpayer makes his/her own decision. Thus, even if 40% taxpayers pay even less per capita than 20% taxpayers, if the tax was 20%. perhaps they would gift even less than they currently gift (after all, it would cost them more to maintain the gift). How could HMRC prove or disprove such a hypothesis?

I shall leave it there; I do not understand the proof – and to me, prima facie it appears strongly counter-intuitive.

They asked them if they understood the relief

They did not

So it cannot have influenced their behaviour

A good piece. “Politics is the art of the possible”

At present most of your tax proposals are pretty straightforward to implement. Many just need a “flick of a switch” as the machinery for implementation already exists.

A wealth tax would require an exercise that would make the Doomsday Book look like trivial.

Let’s just start with the easy ones and see where we get.

Agreed

As you say, there is considerable resistance to a wealth tax. There also seems to be a lot of resistance to inheritance tax, though goodness knows why since few people are affected.

Yet, we have very few property taxes which, as your post shows, constitutes a large proportion of taxable wealth.

As far as I can see, there are only three property “taxes”: stamp duty, council tax, and inheritance tax. Stamp duty is a bad tax because it is a tax on mobility. Council tax is not progressive (it has an upper limit). And inheritance tax is a last ditch attempt to tax capital gain (amongst other things), and doesn’t work well in that regard.

In the USA, that bastion of “capitalism”, they have state property taxes. These vary by an order of magnitude from 0.28% in Hawaii to 2.49% in New Jersey (and they have varying thresholds, so they don’t apply to the whole value of a property). If the USA can do it so can the UK.

Given the ineffectiveness and resistance to the few UK property taxes, should we not scrap them and have a property tax as per USA?

The resistance to a new property would be tempered by scrapping the other taxes, so I figure it is politically achievable.

Sure, initially some people would get away with paying little property tax (because they bought long ago and were not taxed). But, over time, this could become a fair and progressive tax.

I accept there are practical issues. But, if the USA can do it so can we. Most properties are on the land registry, which makes it easy. The value of a property can easily be upgraded every year by the average price increase in the area, which is well known from the land registry. If people are not satisfied then they can pay for an independent evaluation, (similarly a property not on the land registry can be independently valued at the cost to the property owner).

The other issue is of asset rich, income poor households. For example, an elderly person living in a big house in London, that they bought decades ago. I don’t think it’s right that such wealthy people should claim poverty to avoid tax. However, I can see the problem of an elderly person being forced to move and its political unacceptability. In this case a property tax could be made a charge on the property when ownership changes (just like a mortgage is a charge on the property). This should be open to anyone, for simplicity (why not?). No one could then say they couldn’t afford the tax.

If it can be done elsewhere in the world it can be done here. Taxing property seems, to me, to be the most practical wealth tax.

Taxing property is not a solution.

But first, styamp diuty is a transation tax, not a property tax.

And council tax is a serice charge at present.

IHT is a welth tax, not a property tax.

I suggest reading my note on council tax in the inheritance tax series: there are a tiony number nof really valuable properties – less than 1% of the whole. Poperty taxes are not a way to solev our tax problems when there are vastyly easier solutions, which I have explained.

Why not read it Tim?

I read most of your posts and find them enlightening and interesting. I agree with much of what you say. I did read your post, both today and on inheritance tax previously. I found them interesting.

I happen to have a different view and I hope you don’t mind me expressing it here?

We’ll have to agree to disagree on this one.

Thanks for all your hard work. Hopefully it moves things forward, despite the despair many of us feel.

So how are you going to collect significant money from a very small tax base?

The total of council tax, stamp duty and inheritance tax is about £67billion a year (£39 billion + £21billion + £7billion).

Assume the average house price is £290,000. Property wealth is, as you say, £5458billion. Which makes about 19million houses. My figures are very approximate given limited time and data.

Say you set a threshold of £150k and taxed above that at 1.5%. Then an average property would pay about £2000 per year, about the same as council tax. So, the average person would be no worse off.

You would need a strongly progressive property tax rate to make the figures work out. Say you charged 3% above £500k house price. Then houses worth below £500k might yield £30billion (very approximately).

A £1M pound house would yield circa £20k. Apparently, there are about 730,000 worth more than £1M. So, with these rates you would yield (more than) £15billion.

These figures, if you include houses from £500k to 1£M, are not wildly different from the total tax take at the top of my reply. It would need some careful calculation and setting of rates and thresholds to make it work. It would be a big change. But I don’ think it is wholly unreasonable.

But, you are right, to get the yield from property alone is a challenge.

This is a totally impossible way to tax.

I am only interested in what is possible.

We will have to agree to differ.

I’ve been following the way your taxing wealth proposals have built up.

You have considerable insight. It gives me some confidence that there may be a way out of the mess that your other posts frequently shed light on.

Although I despair of Starmer with his latest alignment with Thatcher. That’s going to put his aspirations of a resurgence in Scotland in reverse. Even though the SNP need a sound beating to shake them up.

Thanks

FWIW I have found your taxing wealth series to be well argued and reasonable.

‘Blanket bombing’ by using a ‘wealth tax’ is just giving the dog a bone – it’s a headline and nothing more.

The devil is in the detail – always. That’s where the tax take needs to be.

I hope that this work of yours gathers momentum.

That’s my hope too

It is being noticed

A well argued, well presented and convincing ‘at least to me!) exposition of your position on a wealth tax, Richard.

Like others here, I really hope this and your report get the traction they deserve in places that count (including the despairing Labour party so obsessed with balancing the books, for whom adopting some of you ideas could provide a way out and avoid austerity). GO FOR IT!

Thanks

One idea might be some sort of change in the tax treatment for ‘large’ (ie Luxury) properties, over a certain size.

Eg Chez Sunak enjoys the benefit of the cap on energy prices when its – presumably massive with a swimming pool etc.

If houses like that had to pay ‘business’ energy costs, ‘mansion tax’ etc would that raise money?

I gave no problem with that – but the sums involved are tiny

George Monbiot went in to bat for your proposals on taxing wealth without hiding behind the classic ‘Wealth Tax’ fig leaf. He started out by saying that a couple of weeks ago in the Guardian he had: “rashly attempted to work out what the deficit is across all public services in the UK. What it would take to bring a functioning state, with functioning public services back, and it’s about 100 Billion a year of extra spending would be required”.

Monbiot then pointed out that: “you can do that by, for instance, raising Capital Gains Tax to bring it into equality with Income Tax, there’s a series of…” After a brief dismissive interruption from Joe Coburn he admitted that: “That wouldn’t by itself raise 100 Billion, but there are a series of much fairer taxes that would be redistributive as well as raising that revenue. But we absolutely need to bring back robust public spending on the right things if we’re going to have a functional state in this country.” I think Monbiot has been studying your Taxing Wealth Report!

The Labour MP, Luke Pollard, strategically ignoring the implications of what Monbiot had just said, made a rapid hard right turn to resuscitate the ‘Growth Fairy’. I am so sick of hearing about al the magical ‘Growth’ in response to cuts and zero investment. I had a 13 centimeter ‘growth’ on my right kidney and I was Fxxxing ecstatic when my surgeon cut it out!

He has read the report.

I sent it to him.

Your last comment very good. I hope all is now ok.

The flip side of austerity during the 2010s is that some people now have significantly greater wealth. If some citizens have accumulated wealth due to being under taxed do you think we just have to let that go and start taxing from now?

My point is that we could waste many years posturing around a wealth tax and not get one.

Or we can actually tackle the issue.

Which would you prefer?

Both of course!

You can deliver quicker results without creating a new tax, but is it practical to make a significant change to the wealth profile of the country by only taxing income?

Can a fairer society be created without taxing back some of the accumulated wealth?

Thanks.

When we have taxed income from wealth better than we can move in to wealth, if needed

Give it a decade or more though

Until then, I will concentrate on what needs to be done.

What I can say is that while I understand WHY people call for a wealth tax, I am more than happy to accept Richards explanation of why it wont work and what the alternatives are.

Thanks

We just need to call it a wealth income tax

Richard - You have compiled so many terrific options. I particularly liked the notion of adding progressivity which reduces the resistance of the mass majority of people. I think adding modest exemptions to some of your measures would add to that strategy. My one suggestion would be that you narrow your definition of capital gain, by not having land qualify as capital. That would increase the tax on the massive land holdings that you detail

Note: In Canada there is no inheritance tax, but everything is deemed sold upon death which may have the same cash flow effect.

Since I argue that gains be taxed at income tax rates I am not sure of the advantage of decking land sakes not to be gains.

I gave proposed that capital gains and not inheritance tax apply to land disposals on death.

I think we are in the same ballpark.

Good article. ‘Wealth’ taxation is not very popular with voters because the ‘perception’ is it means the Government taking something someone owns. Those who argue “most people won’t pay it” miss the point, most people would ‘like’ to be wealthy (why else do people buy lottery tickets?) and, if they were, would to take a dim view of the Government taking some. Hence they still feel it an unfair tax even though they are not the ones paying it. What we need are many people, on social media, with mates in the pub whenever a ‘wealth tax’ is mentioned to make the case “No it’s a tax on ‘income earned’ from wealth that is needed”

While I accept your argument and your tax proposals and would like to see them implemented, the thing that I’m uncertain about is the likely response of ‘the markets’. What responses would be likely, and what could a courageous government do about them?

Similarly, while – like you – I’m appalled at the harm being done by the Bank of England’s interest rate policy, what kind of political strategy would be needed it to reform the BoE? And again, what kind of response and resistance is such reform likely to have to contend with?

Good questions

I would like to write what I am calling ‘The Plan’ to address those questions.

But other projects are in the way.