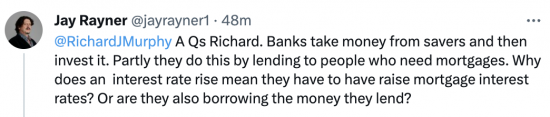

I was asked this question on Twitter this afternoon:

This was my reply (over six tweets):

Thanks for your question Jay. Your question is based on a common misconception that banks lend savers' money. Actually, they don't. The Bank of England finally admitted this in 2014. When a bank lends, it creates new money out of thin air. There really is a magic money tree.

That new money then creates deposits in bank accounts. In other words, lending creates savings. But savings are never needed for a bank to make a loan.

All this is because money is nothing more than debt. If I promise to pay the bank £20,000 and they promise to pay £20,000 to the garage I want to buy a car from our mutual promises to pay create that new money. And when the loan is repaid that money is cancelled.

So what do savings do in the macroeconomy? Absolutely nothing at all in most cases. Banks know that. That is why they are so reluctant to pay for them. They are cheap capital for them, maybe, but that's it. They're just dead money.

That's also true of most pension saving by the way - when most is saved in second-hand shares and second-hand buildings and no new value is created by the saving, at all, in mostly cases.

If this was properly understood we could radically change our economy for the better. It isn't understood because the powers that be (banks and big finance) want us to think they're really useful. Mostly they're not, and won't be until we make them funders of green investment.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

Hunt and now Labour are saying they can’t help people to cope with the higher interest rates and rents -even in the worst cases, to keep their own homes, as it would “be inflationary.” I am wondering are they wrong or have I missed something?

The extra money the banks are raking in due to the higher interest rates is not loan repayment money but profit. Some will paid out in higher dividends (which of course is not inflationary like raising salaries for doctors and teachers !) However, I assume most of that will simply boost their reserves and not go into general circulation in which case how can it affect inflation?

I have considered the argument it not withdrawing huge sums necessary they say ‘to fight inflation’. But higher energy prices and prices for essentials like food and petrol leave the public with a lot less to spend and their wages have not kept pace with prices. Demand is already threatened. So I dismissed that one.

My feeling is that people are being sacrificed -not to use William Jennings Bryant’s phrase, on a cross of gold- but to an ideology of banker-ism. A false god. If so then, sadly, we have been here before.

You are right about the sacrifice Ian.

Hi Richard. Just wanted to congratulate you on the work you are doing at the moment. I wondered if you’d seen the survation poll which had shown that the majority of those questioned thought that prices would come down if inflation was halved. It shows there’s a massive job to do in terms of educating people on even basic economic concepts. With that in mind, I find a lot of the finer points of MMT elude me and I struggle to follow some of your blogposts (like the one above). I can see with the creation of a glossary you’re moving in the right direction for demystifying the finer points of macroeconomics for the layperson. Perhaps there is more to be done? For example accessible, short videos and diagrams for those who like to learn visually. I have tried to convince friends and acquaintances about some of your points and then find myself on increasingly shaky ground – are there any existing resources I can point people at which explain this stuff easily? It’s going to be hard to win the argument unless people can understand the conceptual framework. I do appreciate that it’s hard though. Thanks again!

Hove you looked at my YouTube’s?

There are more than 100 of them.

“So what do savings do in the macroeconomy? Absolutely nothing at all in most cases. Banks know that. That is why they are so reluctant to pay for them. They are cheap capital for them”.

This is why it is so egregious that the BoE pays the Banks interest for their demand deposits at the BoE (CBRAs); which are required solely because of the appalling, unforgivable failure of the Banks in 2008. What makes this even worse, the commercial banks insist they require interest on money the central bank requires solely because of the poor risk record of the Banks when the CBRA regime we have was not in place.

Ironically; indeed perversely, at the very same time the commercial banks have the bald audacity to pay zero interest on demand deposits held by the public in the commercial banks. The public would be unlikely to hold the deposits in the commercial banks that they do (for zero interest), if it was not for the £85,000 security over deposits in UK banks provided by the Government. The BoE and Government are thus actually paying interest and providing guarantees to TBTF Banks so that they can earn vast windfall profits from both the public and the Government/BoE for zero effort and, in the reality of TBTF, zero risk.

One solution is to reintroduce minimum reserve requirements (CEPR; ‘Monetary policies that do not subsidise banks’, Paul De Grauwe Yuemei Ji / 9 Jan 2023). This would no doubt require restructuring of the 2008 solution; but that was created in an environment that wanted a fix that efffectively exonerated the Banks, left them largely intact, and effectively retained their TBTF status; and that combination of risibly inappropriate objectives has been achieved; but to no good economic purpose for the public, or their prosperity, rather than primarily the prosperity of a banking sector that is merely financialising everything in their own vested interest. Commercial banking remains a major part of our economic problem. It is not fit for purpose.

Thanks

That example with the garage is helpful, but it raises more questions. What are the limits to this kind of lending – I get that the bank will have its own limits, like a guess of whether the recipient can repay the loan, but is there some kind of functional upper limit to how much a bank could loan, if it really can make money out of thin air?

And a more facetious question, how come a bank is allowed to make money but I’m not?

Banks are licenced by the BoE. You aren’t.

The limit is the number of credit worthy customers .

Absolute nonsense.

If no-one could sell shares to other people, then no-one would buy share as part of their pension in the first place, and companies would not be able to raise capital. The whole point is that the secondary market liquidity is what makes company shares attractive for pension investors.

You do know fewer than 1% of U.K. companies are quoted and shares in the rest are valuable?

Try stop talking nonsense

You appear not to understand the difference between shares being quoted and shares bring tradeable, which is obviously the key point being made.

I note you used to be Sarah Pascoe

It’s wrong to say that savings create “cheap capital” for banks, as savings have to be repaid by a bank, whereas capital can be lost if the loan turns out to be bad and can’t be repaid in full.

What you should have said is that savings may create “cheap funding” for banks, although whether savings are considered cheap or not depends on how large the savings deposit is and how much it actually costs the bank to administer the savings in the bank account. Multi million pound deposits (assuming paid below the market rate of interest) could be considered cheap but small deposits £1,000s or less are unlikely to be cheap funding for a bank given the associated costs.

Banks are legally required to hold “at risk” capital that can be lost if the bank loses money – e.g. if the loan is not repaid or is only partially repaid. The amount of banking capital required is strictly controlled by regulation (see https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/prudential-regulation). Banks can only create loans in the way that you describe if they have already have sufficient loss absorbing capital to support those loans.

No, I meant capital

I am interested in substance, not pedantry

According to credit creation theory of money, central banks buy mortgages from home holders. It is the home holder who offers the interest rate to the bank. There is no need for a home owner to offer the central bank rate to their mortgage provider.

Now shall we live in the real world?

I couldn’t agree more.

What we need is to make people more aware of is just how much fiat money is created by banks as credit.

We need to see figures and ratios of how much money circulating is debt, as opposed to earnings and savings.

Then we need to ram it down the public’s throats until they get it. And our politicians more to the point.

Sorry – but I’ve heard so much bull shit on the radio today – the talk about making a recession happen on purpose to stop inflation!!!

Which is what Richard has been saying about the the BoE’s intentions for some time.

It’s not the bloody economy that is stagflating – its the damned ideas about how to run the economy that are stagnant, whether in Tory land or Stymied’s Laboured.

I never seen such………..dumbness in all my life. ‘Dumb’. That’s all I can describe it as.

I have the impression that those criticsing the post have not read the BoE’s 2014 report – which is a pity cos it is well worth a read.

Perhaps these critics would learn something , or perhaps not, horses, water etc.

Hi Richard,

I’m glad Jay asked and I’m glad you replied.

When I saw the phrases “there really is a magic money tree” and “banks create money out of thin air” it reminded me of how powerful framing can be, and how we can get trapped in someone else’s frame.

Professor George Lakoff, author of “Don’t Think of an Elephant” advises not repeating the phrases used by the people who disagree with our views.

Because doing so helps to reinforce those ideas in their head. It entrenches them neurologically. The more a phrase is repeated, the stronger the neurons associated with it become, and the harder it is for them to listen to new and/or alternative information and ideas.

So, for example, if someone already believes that “there is no magic money tree” they will more than likely resist, very strongly, the idea that “there really is a magic money tree” precisely because it goes against their neurologically entrenched concept.

Instead, Lakoff suggests, people are less likely to resist and reject our ideas and the facts if we use concepts and phrases that don’t activate their pre-existing neurological concepts.

Lakoff suggests a sandwich consisting of stating which values we believe in, why they’re important and which facts support them.

So, in the case of magic trees and thin air, it would be more effective to avoid those words and concepts.

Culturally, the idea of money not growing on trees is very deeply rooted. It’s used as a joke and pejorative, to deride someone’s ideas as nonsense.

Similarly, the concept of magic and things being produced out of thin air are also associated with the incredulous, and not to be believed as being real.

It might be better then to evoke different concepts using words that don’t trigger those deeply rooted, negative ideas.

Consider this more literal frame for instance:

Question: when you take out a mortgage, does a bank lend you someone else’s savings?

Answer: No. They haven’t done that for hundreds of years. Nowadays, the bank creates the money for you in their spreadsheet and adds it to your bank account.

The false knowledge of how banks provide mortgages them becomes framed as “hundreds of years out of date”. And if something is that out of date, it can and should be thrown away – just like mouldy vegetables. Who wants to be seen as being hundreds of years out of date?

Visualising numbers being added to a spreadsheet, and to our bank account, is easy and commonly understood.

Who could deny that banks use spreadsheets and their own bank account has numbers in it?

The Guardian wrote a piece on Lakoff’s research too: https://www.theguardian.com/science/head-quarters/2017/jul/20/the-power-of-framing-its-not-what-you-say-its-how-you-say-it

Noted

For that reason I keep writing to progressive groups asking them to stop using the expression “taxpayers’ money”.

Quite right too

Thanks for bringing this up, Lee. You make a very convincing argument that we need different framings and concepts if we are to make a breakthrough for convincing the public about the usefullness of MMT.

I have had some thoughts about how to reframe this argument for some time. This is the first time I’ve put them in to writing, and I am not sure if the metaphor works as well as it does in my head, but hopefully this might serve as a good starting point to refine this idea:

-Money is the “blood” of a nation’s economy, “transporting” and “delivering” resources across the economy like blood delivers nutrients and oxygen and removes waste products to and from cells.

-Just like our body needs a certain amount of blood to work effectively, our nation needs a certain amount of money circulating in the economy to work as well (what we call the national debt)

-In the last decade and more austerity has deprived money from the economy, making our economy “anemic”. On top of that, our economy has suffered significant “blood loss” due to the combined effects of Brexit, Covid, the war in Ukraine, and the resulting inflation from it.

-As such, printing money in this context would be the equivalent of giving the economy an urgent and necessary blood transfusion to restore the “patient’s” health.

-These “blood transfusions” will continue until our economy is restored to full health, here defined as full employment with everyone earning the living wage or above.

I will admit that I am not a medical expert, so I do not know if the medical/biological metaphors are accurate. I am also not sure how best to describe the requirement for redistributing wealth (e.g. taxing the rich, Richard’s proposal of directing pensions and ISA savings to Green New Deal investments, etc.) with the same metaphor. Perhaps those more medically inclined reading this comment might come up with some better examples, or point out to me where the metaphor breaks down?

Thanks

My problem with the metaphor is that blood is real and really does move

Money is just debt and it literally never changes hands (cash is not money – it is a token representing money because money is only ever debt)

So the metaphors does not really work for me. But worth doing

Simple question.

Housing is a necessity. Why will increasing the cost of a necessity reduce inflation?

If making essential items more expensive reduces “inflation”, does it not suggest that indices of inflation are measuring the wrong thing?

Yes

Seeing housing as a necessity is plebian doublespeak. It’s a profit-making scheme for a select few.

Do keep up old chap!

I think that your answer to Jay Rayner was largely correct, but not totally. Both the BoE and the Bundesbank have better explanations.

The correct bit is that deposits are not a prerequisite for making loans ie loanable funds theory is 100% wrong. Banks do not take in deposits from savers and then lend them out as is still taught in schools and universities. The second correct bit is that when a bank makes a loan it also simultaneously creates a deposits. So far so good…

Where care is required (and the Central Bank explanations are better) is to extend this to an idea that deposits are dead money and/or not required. The loans still need to be funded and that is what deposits and or wholesale funding do/does. They are not a redundant entry on a banks balance sheet. The Bundesbank explains this in a precise manner, the BoE uses the example of mortgage lending.

So, they are honest about committing a con trick and putting depositors at risk as a result, excepting the fact that government’s guarantee that depositors don’t lose and banks get very low cost capital? I admit, I did not spell that out.

Sorry, but I disagree you and the banks. Deposits provide cheap buffer funds for bank losses, maybe. But they never find loans.

Thanks for the reply. TBC, you are disagreeing not just with me or commercial banks, but with the BoE, Bundesbank and the Swiss National Bank to name a few…in short, you are not representing what the BoE and others are saying about money creation faithfully.

There is a key distinction between debunking the notion of banks being intermediaries who take in deposits FIRST and then lend them out and the claims that you are making.

The Bundesbank states it like this

“This refutes a popular misconception that banks act simply as intermediaries at the time of lending – ie that banks can only grant credit using funds placed with them previously as deposits by other customers”.

Many people miss the not so subtle “placed with them previously” bit here. This is a mistake because the Bundesbank follows this with

“ Despite its ability to create money, a bank still has to fund the loans it has created ”

The BoE and the Swiss National Bank makes the same point.

On the buffer, I think you are confusing ST liabilities (deposits) with capital (equity). It is the latter not the former that provides the buffer to absorb losses – hence the fact that banks have capital requirements that they must fulfil. Deposits would be a very poor buffer since they can (largely) leave the bank at any moment – they belong to customers not the bank (as the SNB stresses when it debunks the “out of thin idea” narrative).

The mistake that you are making – which is a partial one – is common especially among MMT economists (Werner gets this wrong, for example). The key point that the Central Banks were making in 2014, 2017 etc was that neither reserves (money multiplier approach) nor deposits (loanable funds theory) are PREREQUISITES for loans. But they all also state that both are necessary parts of the process and are needed to fund loans.

HTH

I disagreee

That is banker bullshit

Capital is required to make loans and they use deposits as capital – backed by state guarantee

Of course I disagree with them

Their claim is false

Desposits are not needed

Captial to absorb losses is

They use deposists as capital – and that’s fraudulent

Thanks for posting my reply and for responding. I must admit that I am surprised to hear an accounting prof make such claims!

Banks’ capital is the difference between its assets (eg loans) and its liabilities (eg deposits). It cannot by definition include its liabilities. Capital is indeed required to make loans – and as you say, to absorb losses – but deposits by definition (a liability) and nature (they can walk out of the door at any time) are not part of this buffer. They are a source of funding as the central banks make clear.

If banks are committing the fraud that you claim why are CBks, regulators, governments, shareholders etc not doing anything about it?

If you knew anything about accounting (and you very obviously do not) you would know there are no distinct lines between liabilities and capital and many liabilities are now capital, and even vice versa, in accounts

And that is before we consider the impact of government guarantees

I suggest you are way, way out of your depth. Come back when you have learned a great deal more.

Jens said:

TBC, you are disagreeing not just with me or commercial banks, but with the BoE, Bundesbank and the Swiss National Bank to name a few…in short, you are not representing what the BoE and others are saying about money creation faithfully.

I cannot see how the 2 halves of this sentence match. Clearly Richard is disagreeing with Jens and the commercial and central banks. That does not mean that he is not representing what the banks are saying faithfully. Complete non sequitor.

I wonder why Jens felt the need to pretend that Richard is misrepresenting the banks?

🙂

@cyndy

The answer is that Richard is only partially representing what the Central Banks are saying in terms of money creation. The bit he gets right is the fact that neither deposits nor reserves are prerequisites for lending as I and many were taught in the past at school and Uni eg loanable funds and the money multiplier.

The bit he gets wrong – and fails to represent the Central Banks arguments faithfully – is the argument about the role of deposits. He contradicts what those who are responsible for the functioning of our money systems say about the role of deposits – I quoted directly from their articles often money creation in my posts – and much to my surprise in explaining wrongly the basics of bank accounting and the distinction between capital (which acts as a buffer) and deposits and other liabilities (that do not and cannot).

The post where I quote the BoE has not been accepted and I doubt this one will either. This is a shame as those who need to learn are being prevented from doing so…

That was your last post

And let’s be clear you are using the last defence of the pedant – relying on the rules

But political economists and accountants look at the substance of transations – and you clearly do not undertsand that and so your comments are just wrong

There are huge differences between capital and liabilities, that you suggest otherwise tells us what we know about your understanding of banking regulation.

Oh dear…..just go and read the massive literature on this

Thanks for the reply. As far as my accounting knowledge goes, what I do know is that “Capital, in its simplest form*, represents the portion of the value of a bank’s assets that is not legally required to be repaid to anyone”. In other words, it does not, indeed cannot include deposits (indeed part of its function is also to protect depositors).

* note, that there are certain more sophisticated forms of allowed capital that may be repaid in the long term

The simples way to square the circle here, would be to show where and how deposits are included in any bank’s capital ratios. This information is publically available and so this should be easy to prove or disprove. I have yet to find any evidence of banks using deposits in this calculation, but m happy to be show where this has happened….

In the meantime, I went away and checked the BoE website and unsurprisingly found

“Capital can be considered as a bank’s ‘own funds’, RATHER THAN borrowed money such as deposits.”

“There are two other important characteristics of capital. First, UNLIKE a bank’s liabilities, it is perpetual: as long as it continues in business, the bank is not obligated to repay the original investment to capital investors.”

If I go to HSBC and ask to withdraw money from my deposit account, HSBC is obliged to pay me that money, Hence, my deposit cannot and is not part of HSBCs capital.

HTH

And as I note, most of what the abkmsays is wrong

They still do not acknwpeldge how QE really works

Most of the ntime they behave as if banks are intemediaries and they are not

And you are buying their falsehoods

I can’t change that

I can just tell the truth

Jens says “The key point that the Central Banks were making in 2014, 2017 etc was that neither reserves (money multiplier approach) nor deposits (loanable funds theory) are PREREQUISITES for loans. But they all also state that both are necessary parts of the process and are needed to fund loans”.

Now I may be a bear of a smallish brain, but if something (e.g. reserves/deposits) is needed for something else (loans) to exist then having that something must be a prerequisite, so Jen’s statement (and therefore the Central Banks position) is nonsensical double speak.

And if Jens is right, where are these funds that back the loans?

Jens says that the difference between assets (loans) and liabilities (deposits) = capital

Banks make lots of loans – currently around £1,675 billion at end of 2023 Q3

Banks hold some deposits (savings) – currently around £280 billion

BoE reserves = £400 billion

So by Jens definition, total banks capital is around £1,000 billion. And Jens says that reserves and deposits are needed to fund loans, but they only account for £680 billion. So how do banks “fund” the remaining £1,000 billion?

I don’t have any answers by the way. The whole thing makes my head hurt! But somewhere, inside all of the figures and the obfuscations from the government, the banks and the media, there is an important truth struggling to get out. Sometimes I feel I’m almost in touching distance of it and then it slips away. And when people like Jens come along, I wonder if their entire purpose is simply to derail the discussions and push us all into the sidings as we expend effort and time trying to fathom out or refute their arguments.

So what are the funds that are backing up that capital?

I am not sure where you numbers come from…

Banks will lend as much as they can to borrowers they deem credit worthy. The constraints are regulatory.

Banks DO have to borrow to make a loan…. but at the outset the loan is ‘self funding’; if I take out a loan the money appears in my account which is a deposit. When I transfer it to the car seller they become the depositor etc. Of course if we bank with different banks then there is a movement of reserves; my bank (all things being equal) will need to borrow those reserves back…. but there is a natural lender – the car dealers bank. That interbank lending will happen at a slight premium over the policy rate that the BoE pays on reserves… else the car dealer’s bank would not bother.

So far, so good. I don’t think anyone is challenging this. Where the BTL disagreements occur I think it is on the definition of “capital”. In banking it has quite a tight meaning but economists and accountants take a broader definition.

The ‘license to print money’ that banks enjoy is not gross interest received but net interest margin. Given the huge amount of reserves in the system and the low rates paid by banks to depositors this NIM is a big and rising number…. but banks do have deposits to match their lending.

Thanks

That makes total sense

Indeed it does and Clive makes the same point as me and central banks.

Ie, banks do need to fund the loans through deposits of other forms of borrowing but not at the outset. That is the key. Too many misunderstand this and go from how money is created to the fans idea that deposits are not need to fund the loan or can be a part of capital.

Clive is being polite/diplomatic about the definition of capital but perhaps he could answer specific questions:

1. Are deposits part of banks capital – from a regulatory and operational perspective?

2. Do deposits acts as a buffer against losses in loans or other interest-earning assets?

An interesting debate, thank you. While I stick by my (and the BoE, Bundesbank, SNB, ECBs) I have learnt from this exchange notably from Lee’s excellent post and the link to Lakoff. Every day is a learning day….

You entirely miss Clive’s point

The Bank dies not need the deposits

De facto, it creates them

I only have a tenuous grasp of monetary/fiscal matters. I hang on to the naive belief that money is just an artificial construct that seems to have an increasing disconnect with value. I yearn for the implied simplicity of Ann Pettifor’s “We can afford what we can do.” that places the focus on resources.

That said, this artificial construct appears to have really got us tangled up in our own knickers.

Your exchange with Jay Rayner prompts a few question…

Does a mutual society, such as Nationwide (which states it is not a bank), operate in a similar manner?

Are there disadvantages in using deposits to fund loans, e.g., the risk of deposits being withdrawn if savers’ confidence is lost, or if inflation forces them to draw on their savings?

Accepting that banks can and do create money, as you describe, I assume that banking regulations require that banks maintain a deposits to loans ratio or some similar mechanism; otherwise, how would the Bank of England/Treasury have any control over money supply?

1) The Nationwide is a l bank so it operates like all other banks

2) Credit unions prove the problem with funding loans with deposits – it is not viable and illiquidity risk is high

3) The requirement to hold reserves is via the BoE to ensure inter bank settlement can be made

Jens, I always try to be polite. But I did mean what I said about ‘capital’.

Even in banking the world it has several meanings. I worked a while in Debt Capital Markets for an investment bank….. companies raise capital by selling bonds; not all capital is equity.

In direct answer to your questions; no and no.

Thanks Clive

I have no argument with Clive or the direction of this debate. I merely wish to suggest it has a flavour of an elegant ritual dance; forgive me Jens, but oozing formal complacency.

If you go to the bank or building society to withdraw your deposit, the bank/building society is obliged to pay it. Of course it is; but that does not mean you always receive it; as the Northern Rock depositors found in 2007. The conventional answer is, that was, of course before the current regulations were enforced (critically on reserves). What is that worth?

Part of the post-2008 UK system is an £85,000 guarantee for bank depositors (for the public, not really the corporates); which I consider is necessary; but less than a glowing endorsement of the Banks or the system (or the discussion just concluded?). Then we look at the current turbulence in Banking (SVB in the US etc.); or in the UK, the bizarre LDI crisis; in pension funds! Pension funds! Far from building decades of success, we seem never far from unforeseen, new crises; just averted by the skin of our teeth. I do wonder if I have been reading a charming, heart-warming fairy-tale, spun on a web of candy floss.

I overstate my case, but it is an intuitive response to an endemic complacency I perceive around the banking system, its apologists and the effectiveness, and even understanding of our Central Bank. The BoE have effectively acknowledged they do not understand the current monetary problems, for heaven’s sake.

Thanks

To definitively illustrate Richard’s point about the origin of banks’ capital, I offer a sentence from the Summary Financial Statement in my Cumberland BS Annual Review received this morning, “Our capital comes from retained profits”.

What confuses me is the fact that their is competition through interest rates for depositors. And in the Silicon Valley Bank situation, losing deposits was a major part of the crisis for them. I certainly agree that banks can and do create money. They lend as much as they can profitably to credit worthy customers. However my impression is that they have time and demand deposits and other instruments which are a source of the majority of their loans.

The money supply only grows a few percent a year. I feel like banking is bigger than loanable funds, but still relies on loanable funds.

I am not sure what you are getting at here