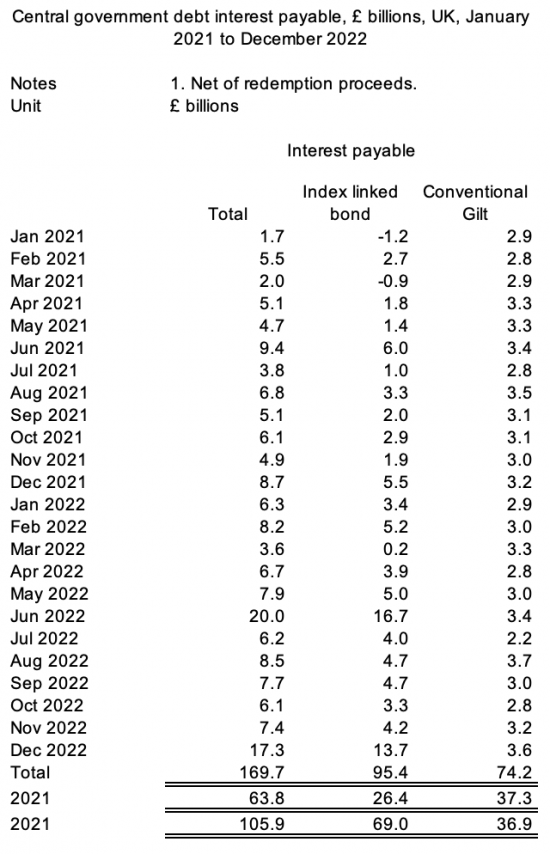

I have been asked a number of questions since returning to the issue of the excess interest payments recorded as a result of the extraordinary accruals being made for redemption costs in indexed linked bonds. As a result, I have prepared the following table:

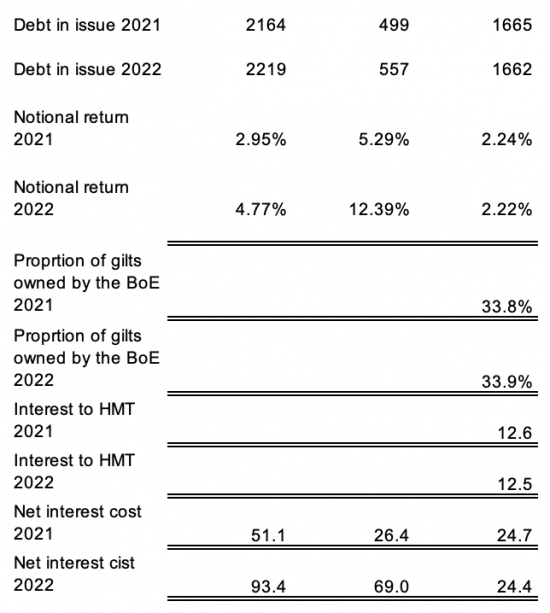

The data initially comes from the Office for National Statistics. That on gilts in issue and Bank of England holdings is from the latest Debt Management Office publication, which is the best available.

What is apparent is that the issue being addressed here relates entirely to index-linked bonds. There is no issue with conventional gilts.

The rate of return on index-linked bonds has risen in line with inflation, hardly surprisingly. However, as inflation tumbles, as it will, that rate will also fall. In fact, it is possible it will become negative, as the data shows is entirely possible. In other words, this is a very short-term phenomenon.

Simply equating the rates of return, there was an excess cost to index-linked bonds in 2022 of about £57 billion. That calculation could be refined: it would not much change the conclusions if it was.

If that excess cost was spread, as I suggest appropriate, over the 17-year period that these bonds have, on average, remaining in existence then the cost to be recorded in 2022 would have been approximately £3.4 billion, which comes in at neither here nor there.

Instead, it has been recorded as if an excess and continuing cost when it is neither. My suggestion is that this is deliberate misaccounting to fuel the austerity agenda.

When accounting is used in that way it has ceased to be objective, true or fair and the Office for National Statistics should know that. Whatever the accounting standard they use, there is always a true and fair option they can use for reporting for decision-making purposes. They are not using that option and that is, in my opinion, a gross failure on their part.

No only is the interest ion the national debt the sum they report because they do not state it net6 of sums paid to HM Treasury, they also deliberately overstate the cost of index-linked bonds that have to be accrued over their life. Accounting failures do not come much bigger than this. The overstatement of interest cost was approximately £66 billion (£57 excess cost of gilts less £3 billion apportioned cost plus £12 billion of interest paid to the Treasury). That's a fail in anyone's book.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

Not sure what I can add to what I have said before…. except that we must still keep “banging on” about this.

The table begs the question – “What is going on with the payments associated with I/L gilts that makes the 2022 so much higher?”

First thing to note is that the monthly data is quite “spiky”. This is because interest is actually on gilts twice yearly. In the conventional market this is spread across the year fairly evenly but in the I/L market coupons are concentrated in June and December. This is why we “accrue” interest to avoid these monthly bumps and troughs in order to give a “true and fair” picture. But, if we take “whole year data” then this spikiness comes out in the wash… and we are now able to compare 2021 with 2022…. and the amounts of interest paid in a given year should be the same (with only minor dicrepencies) whether we look at things on a cash or accrual basis.

So, lets follow the cash!

The difference between 2021 and 2022 (£69bn versus 26.4bn) can only come in two ways.

1) a change in the interest paid on the existing stock of debt and 2) interest paid on new debt issued in 2022

1) The stated real interest rate on a gilt is fixed at issue so the change in the cash paid will only increase by the uplift in RPI (say 10%) – that takes us to about 30bn.

2) Issuance in 2022 is offset by redemptions in 2022. The DMO tells us that the (not uplifted) amount of I/L gilts declined marginally from 362bn to 359bn. So the extra interest that the ONS claims was paid can’t come from there.

So, I hope this shows (in another way) the reason why the ONS is wrong.

Where does the error come from? It is not a “careless error” (to coin a phrase). In the same report of the gilts outstanding issued by the DMO it observes that the amount of gilts (that was unchanged on a nominal basis) rose from £500bn to £550bn on an inflation adjusted basis.

This £50bn can, in no way be described as interest – it is a change in the amount owed,,, which is quite different.

Agreed

But I stress, owed on redemption, to be accrued between now and then

Yes – you are correct to stress that point – it is NOT a cash payment this year (or next) in the way interest is.

I would add that I am not suggesting that this uplift be brushed under the carpet and ignored…. but it is already recorded. It appears as a change in the size of the “National Debt”.

True

But is it debt until due?

And I could record it as debt without including it in the current year charge

Have you sent this to the shadow chancellor and asked her to comment?

No

Because I doubt she would

She highlights her willingness to play within the existing rules

Question. How do UK corporations account for inflation linked debt? Anglian Water (for example) has over half its debt as inflation linked (either a I/L bonds or conventional bons with an inflation swap overly).

I glanced at their last annual report and in note 18 it has a specific line “indexation of borrowings and RPI swaps”.

This number is a large negative in the latest report – substantially more negative than the prior year…. which is what one might expect.

It appears that Anglian Water chooses what I consider to be the correct approach…. but my accounting skills are poor so you might want to take a look.

I will

I have looked

They of course account on a mark to market basis and so effectively provide for the cost that way

The government does not do that and so need not account that way

To coin a phrase: “Not sure what I can add to what I have said before…. except that we must still keep ‘banging on’ about this.” Oh, no too late! Used already! Lets keep banging on anyway. But I am delighted you keep returning to this! I think your analysis rather confirms your point about the unconvincing nature of index linked bonds. I am sure there is a risk profile that could make them look better; but what are the conditions, and what is the risk profile of that probability?

I am a little disappointed nobody among you knowledgeable readership took up the problems I raised about index linked bonds; the endless tinkering required by DMO (with risks attached), the problem of inflation proofing, the matter of deflation floors and the value of indexing without them, and the esoteric matter of principal strip fungibility………… and the real implcations for the credibility of index linked bonds, with all this complexity; espaically in the dangeorous world of digital markets.

I’ll just put this here for now: the ONS say the government accounting has to follow the international standards discussed in the comments to this post from last year: https://www.taxresearch.org.uk/Blog/2022/11/14/were-going-to-have-austerity-on-the-basis-of-some-very-dubious-accounting-for-the-national-debt/

They use six different measures of national debt and three of inflation

They can pick and choose when they want

Thanks, Andrew for referring back to the November thread. Looking through the thread, and comments I noticed Phil Stokoe’s interesting opinion. He wrote this:

“Unless their are periods of deflation, the costs of redeeming an index linked bond will rise each year, and this rise gets added to the outstanding debt each year, and we record that rise as interest in that period.” He goes on to argue (against Richard) that:

“Your proposed approach, for me, breaks the accrual principal – we record transactions when the economic event takes place, and the uplift to the amount owed in principal because of, say 8% inflation in 2022 occurs in 2022 and should be recorded in 2022. I don;t see the logic of recording interest in future periods due to movements in the index in 2022. To provide an extreme example – if the index increases by 8% in this year, then stays perfectly flat for the next 10 years, under the approach in the manuals we’d record the 8% interest now. In your approach that interest would spread over the remaining life of the bond, even when the index is unchanged and there is no change in the amount to be repaid at redemption. That feels wrong to me.” Richard, replied to Mr Stokoe, with four reasons to counter his case; but the one I select here seems most pertinent to the issue discussed above:

“accruals requires substance not form to be reflected in accounting, so the charge must be accrued over the life of the bond. Recognising the cost in full when no payment is due is the exact opposite of accruals in this case.”

That issue of substance over form seems right to me; but I wish to point to another feature that I think is unsustainable, and which the DMO discussed in its index linked bonds papers; the matter of deflation. As far as I can see Mr Stokoe’s whole case is based on the proposition that defaltion can never happen. In the quotations above he begins by acknowleging that “Unless their are periods of deflation”, but then goes on to assume in his argument and example, that deflation can’t happen. His argument does not stand just because deflation hasn’t happened; it stands only if it never happens – and on a subject as recondite as an unkown future, perhaps >50 years from now, he cannot possibly adopt that assumption. I do not believe, on that ground alone the full accrual can stand up.

Here is the view of the 2001 DMO consultation paper on index linked Gilt redesign (the ongoing tinkering), which I think suggests there is a problem with deflation, albeit one that the DMO seems to have some problem grappling with (not establishing a deflation floor does not mean deflation is not an issue, something the DMO here seems aware of):

“Most notably, a deflation floor would reduce the value to HM Treasury of having index-linked gilts in its debt portfolio by reducing their deficit- smoothing properties in some circumstances. Inclusion of a deflation floor would also require primary legislation in order to amend Section 717 of the Income & Corporation Taxes Act 1998 (ICTA).

I do sometimes wonder whether the problem here is not the old, old desire (pre-neo-liberal – but there is nothing new in the world!): to privatise the national debt, by undermining its basic purpose – as both lender and dealer of last resort, the sovereign power’s absolute entitlement and right to defer the capital calls upon it, into an undetermined future, and to future generations.

Yes, there are a lot of technicalities to I/L gilts. Conventional gilts have been around for donkeys’ years so any issues that needed ironing out have been ironed out (the most recent substantial change was switching from “dirty” to “clean” prices in the early 1980s (although that was really a change in trading convention rather than in the T&C of the bond).

I/L linked gilts are much more recent and were originally issued in order to sell long term debt at a time when inflation was very high and volatile. The key point is that inflation risk is a risk that gilt investors are reluctant to take whereas it is not a huge risk for governments. Why, because pension funds’ liabilities are inflation linked… as are government revenues. The issuance of I/L gilts allowed the deficit to be funded at a lower overall cost the UK Treasury.

The problems (minor, in my view) occur because the T&C are fixed at the time of issuance for the entire life of the bond. No retrospective changes can be made without agreement of everyone concerned. For example, from 2005 all new I/L gilts calculate payments using a 3 month lag (instead of an 8 month lag prior top that). More recently the DMO consulted on CPI v RPI linked gilts. RPI linked gilts already issued cannot unilaterally be changed – although new gilts linked to the CPI could be issued if the government chose to. Interestingly, they chose not to.

The issue of deflation was ignored in the early days of I/L gilt issuance – who thought about deflation? Those were the days when 8% minimum guarantees were in place on lots of annuities!. With the world changing this needed addressing but the value of the inflation floor (at zero) is very small. That may change in 30 years time…. but a look at Japan suggests that deflation, if it occurs sees gentle price falls (rather than huge spike as we see in inflationary periods.

An an analogy might be the issues thrown up by rates falling below zero. Some FRNs had a floor at zero, others did not – how do you collect money from a bond holder? There was a big rift in the collateral market on the same issue. However, it was all resolved amicably in the end.

In short, I/L gilts are designed to ensure that the offering to the marketplace meets their needs – because if it does they will pay more,,, and over time, these needs change. Some people buy basic veg, others buy washed and chopped – if you offer both you maximise revenue,

In the case of gilts, it costs very little for the government to provide I/L gilts and it does lower costs.

Noted

Thanks for that clear, succinct and persuasive response Clive. I take your point, and acknowledge your much more relevant personal knowledge and experience of how the markets actually work; which gives your view a substantive advantage over mine.

Nevertheless, I remain very uneasy about your confidence in what I may term ‘the stability of the future’ (for example, the assumption that deflation falls will be “gentle”); and predictable 50 years out. The modern dynamics of digital markets move fast, and the frequency of shocks to the system seems to increase as the amount of lead time offered to Central Banks (who now require to be both Lender and Dealer of Last Resort because if they are not, the system is very likely to fail) seems sharply to decrease; and even then they are found wanting. Prediction of the future is becoming harder, and the justification for assuming that (within statistically narrow oscillations) the range of risk is comfortably manageable seesm to me at best doubtful. For example, I assume the DMO understand these issues, yet in the consultation paper I quoted, were still moved to acknowledge a deflation floor (presumably in 2001, relaxed about the gentleness of any likely effects); “would reduce the value to HM Treasury of having index-linked gilts in its debt portfolio by reducing their deficit- smoothing properties in some circumstances”.

It seems to me the strength of Government deferring capital into the long, ultra or super-long term is attractive because the impact on the future, while it is probably very low, is not just a long way off, but reassuringly ‘unknowable’ (unknowable unknowns), and therefore to all sovereign intents, ignorable. Index linking seems to me an attempted contradiction of the purpose of deferring debt. The whole point is to concentrate redemption far into the future (and allow a secondary market to satisfy holders interim capital demands). I appeciate that may appear over-abstract; but I do not think that is the real effect.

I am happy to be proved wrong: my point is to challenge conventional wisdom; which my experience has shown, time and again, in almost everything – is usually wrong.