I posted this thread on Twitter this morning:

The UK's national debt is a strange figure. For example, to most people's surprise it includes all our notes and coins, as well as premium bonds. But much more worrying is the fact that a significant part of it is created by what I think to be dubious accounting. A thread…

The way the national debt is calculated makes a massive difference when it comes to calculating so-called ‘fiscal black holes', which are the supposed reason why we need to have austerity and tax rises now. But some of the accounting for this debt is dubious, to say the least.

In particular, let's look at something called index-linked government bonds. There were, apparently £540 billion of these in issue by the government at the end of June 2022. On average they are repayable in 2040, which is eighteen years time. See https://www.dmo.gov.uk/media/e1ekgoew/apr-jun-2022.pdf

This is not the moment to explain all the mechanics of index-linked bonds, but the essence is quite simple. The bonds are issued by the UK government. Like all bonds, they are just a type of savings account. There is literally nothing more fancy than that about government bonds.

What is distinctive about index-linked bonds are two things. One is the way the interest paid on them is calculated. The other is the way that the amount of repayment due to the account holder at the end of the bond's life is worked out.

On interest rates, if the inflation rate goes up so too does the interest rate. Formulas are used to calculate by how much, but the impact is pretty direct. So, if inflation rises so too does the government's borrowing cost.

That's a fact. I do not argue with that. But the amounts involved are not that big, overall. There is a cost, but not enough to change government economic policy.

The problem is instead with the way the government accounts for the repayment due on redemption of these bonds. To explain, let me offer a simplified example based on the real data I have already noted. Also assume inflation this year is 10%.

The 10% inflation rate effectively increases the amount due on repayment of these bonds by 10% or (near enough) £54bn. The question is, how to account for this?

Right now the government charges the whole of this £54bn as an expense in the current year. It just increases the deficit and debt by this amount at this moment. This makes no sense at all.

Firstly, this accounting assumes that the £54bn is all due for payment now. But that is not true. On average it is due for payment in 2040. And for accounting purposes money due in 2040 does not have the same value as money due now.

You know this. If someone offered you £10 now or in 2040 which would you take? The money now, of course. If it was £5 now or £10 in 2040 you might be persuaded by the £10 in 40, but if you did what you'd be saying you need a good rate of interest between now and then to do this.

In that case, it is absurd, and just bad accounting, for the government to put the full £54bn in its accounts now. At the very least it should put in a discounted sum and build it up to £54bn by recognising effective interest payments between now and 2040.

But I would actually argue the accounting is worse than that. The reality is the £54bn is not a capital payment. Due to the way the bond is designed it is all interest due as a result of inflation, in effect.

In that case, the £54 billion cost that will only be paid in 2040 should be spread over the 18 years between now and 2040. £54bn over 18 years happens to be £3bn a year. And that is precisely the amount by which the national debt should rise this year as a result of this cost.

The bond will never be repaid early by the government. There is, therefore, no reason to provide for the full cost of inflation now. And the bond was designed to reflect inflation over its whole life, not in any one year.

In that case, providing for any change in inflation over the whole life is the correct accounting for this. But if that is the case the cost of interest would, in this example, be overstated by £51 billion. And that is the supposed black hole in the government's finances right now.

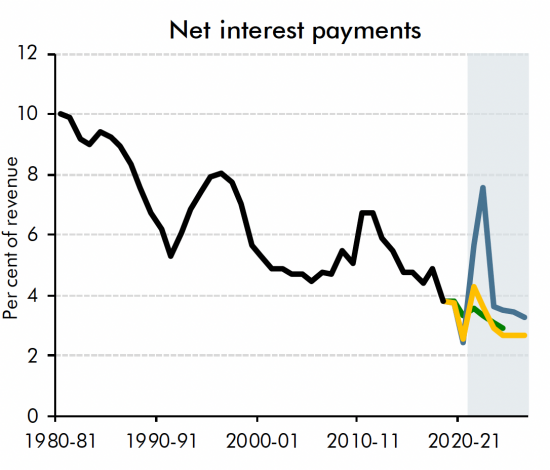

What is more, the government knows this. The forecast of interest costs issued by the Office for Budget Responsibility issued in March this year, by when inflation was expected to rise to 9%, looked like this:

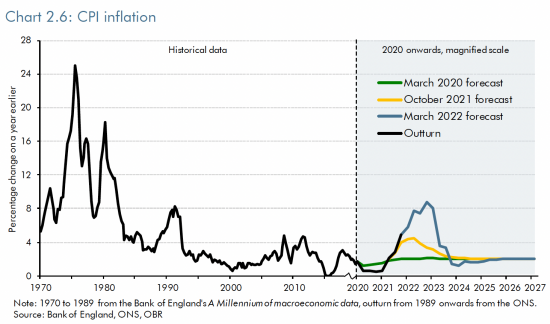

Inflation at the time was forecast to look like this:

Inflation was forecast to peak at 9% in March. The forecast will only be a little higher when reissued this week.

The massive hike in interest costs in the forecast cost of interest in 2022 represents the expected impact of inflation on index-linked bonds, all of which, as I have noted, has been taken as a cost at the moment that inflation happened.

It is also important to note what was forecast with regard to that interest cost after 2022. Within a year or so after 2022 it was forecast to tumble because it was expected that inflation would go away. This forecast will be reissued this week but will look very similar.

This chart explains why today there are news reports that most of the supposed £50bn 'black hole' the Chancellor faces is down to increased interest costs. Not all, admittedly, but most. And now you know why: it is entirely because of this false accounting.

What we are going to have is austerity now because the government will, in eighteen years' time, have a bill of about £50 billion or so more than expected. Spread over the intervening years the cost is £3 billion a year, which in government accounting terms is neither here or there.

Most importantly, there is no money due out now with regard to this cost. The payments are not going to happen for many years to come. But despite that, the government is insisting that we must have savings (or austerity) now to cover that bill.

That's like saying someone must put aside all the money to pay their interest-only mortgage now when the final settlement on it is not due for another 18 years. Of course, no one does that. They save the money, quite logically, over the 18 years so that they have it when needed.

But the government is not doing that. Instead it is insisting on austerity at this moment to pay a bill due in 18 years. We must suffer today as if we were going to pay this cost in full today when we aren't, and when putting aside £3 billion a year for 18 years will cover it very nicely.

In other words, we are paying an enormous price for this dubious accounting. We do not need austerity. Nor do we need tax increases (except on the wealthy). We could, in fact, spend more, because the government has almost no extra costs for this reason right now.

Instead, households are going to be crushed with bigger tax bills. The public services will be punished. People will not get the pay rises they deserve. The NHS will be pushed over the edge. And all because the government is insisting it must have the cash now to pay a bill due in 18 years' time.

I have been corresponding with the Office for National Statistics on this issue for some time now. I have been trying to get this accounting changed. I am not succeeding, so far. So it's time to go public on this, because it really matters.

What I can say with certainty is that the government is aware of this. So is the Office for National Statistics. So is the Office for Budget Responsibility. They all know that austerity is being imposed to pay a bill that is not due for eighteen years. They must all know that austerity is not needed then.

My hope is that Labour also realises this.

So why is it agreed that we must live within 'constraints' (the jargon word, heard a lot from all commentators yesterday) that simply do not exist? What is the reason for this false debt narrative that is based on dubious accounting for a bill not yet payable? I wish I knew.

What I do know is that good accounting matters, but we are not getting it here. The cost will be misery, lives lost and untold harm to the life chances of many more - including all the young people who have already endured Covid.

Accounting can be a force for good. On this occasion it is being used to impose harm. And in my opinion that is unforgivable.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

There are links to this blog's glossary in the above post that explain technical terms used in it. Follow them for more explanations.

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

Buy me a coffee!

Buy me a coffee!

Frankly, it’s a country attacking its own citizens, a betrayal of monumental proportions based on a concatenation of lies. The purpose, of course, is to flog the great prize, the NHS, incidentally making many Tories and some other party members very rich. This includes Starmer, Streeting, and other client politicians of Chinn etc.

Saw your thread on twitter and agree about the accounting nonsense. I find it puzzling that the government have reverted to the insanity of the Osborne era, namely using inappropriate numbers to justify things that are unnecessary and counter productive. I cannot really understand why they have not learnt the lessons of that experience. Perhaps, the mistake again of thinking that running a country is like running a business?

It’s more likely they’re motivated by the prospect of personal gain, IMO.

“The ONS and OBR know this. The government is aware.”

I would not be surprised if you felt they were not. Ideology drives out pragmatism and reality, and this is an ideological government. So they are incompetent or they are lying.

Will Labour expose it? I am not hopeful. What about the SNP and Liberal Democrats? I am not asking for an answer. Just hopeful that somewhere in Westminster we have the expertise and the integrity.

PS 7 lines from bottom ‘dubious accosting’.

Thanks

Will edit

Hi, Richard

Is the current financial position something that UK/America/Europe have a hand in.

Chris

There are global issues, of course

We are making them much worse locally

I thought you didn’t believe in discounting interest rates – I’ve seen you rail against doing so on various occasions before. Now you seem to be pro-discounting.

Either way, the increase in interest payments is down to the increase in inflation causing linker coupons to increase dramatically as well as nominal rates being higher so basic deposit rates also cost more.

You are mixing up coupon and redemption payments for the interest cost – redemption doesn’t play any part here.

Of course, redemptions on the linkers have also massively increased as well. Given the national debt is given as a total, nominal number without any present value calculation, the increase in inflation has directly increased the nominal value of the national debt.

Basically, you’re wrong on all counts.

It’s a shame you start with an ade hominem, and it all goes downhill from there.

Redemption is what this whole thing was about – and that the increase is an effective interest cost to be accrued over time

You clearly did not understand that. Instead, you are simply saying the status quo is fine without any justification at all

I wouldn’t bother again

‘So why is it agreed that we must live within ‘constraints’ (the jargon word, heard a lot from all commentators yesterday) that simply do not exist?’

Possibly to set the Government up to claim that their decisive action (and the sacrifice we have all made together) has brought down inflation? Inflation that was going to work it’s way out anyway. Then, it can justify boosting Government spending ahead of the next elecion. Confirmation that only the Tories can be trusted to manage the economy…

I don’t think your comment “But I would actually argue the accounting is worse than that. The reality is the £54bn is not a capital payment. Due to the way the bond is designed it is all interest due as a result of inflation, in effect.” is correct. On index-linked gilts both the coupon payments and the principal repayment are adjusted in line with inflation. So if we suffer 10% inflation, all future interest payments are 10% higher and the repayment amount at the end is 10% higher. I agree with your central point however, the full cost of the increase in the principal amount should not be taken in the current accounting period.

I deliberately said I had simplified the explanation and did not dispute that on interest

I was only disputing the end payment

You are wrong to say the principal repayment does not increase with inflation

I didn’t say that

So you are wrong

My whole point was to discuss how to account for that

As an exercise in missing the poiiujnt your comment is off the scale

I have been waiting for you to return to this, Richard. There are several extraordinary features of this accounting treatment.

1) It is still not clear to me what the ONS, Treasury and BofE acknowledge IS the accounting tratment. As I have understood the situation, all three refuse to comment officially on it. Have I missed something?

2) The decision to pay the inflation cost as an interest cost rather than a capital cost requires not just to be acknowledged, but both explained and justified; because it appears to breach both sound accounting conventions, or indeed the fundamental principles of the time value of money; and common sense.

3) This brings me to a further explanation required. Who is responsible for establishing this perverse accounting treatment iof UK Bonds; since, unless interest rates were guaranteed not to be high or volatile, how could this conceivably offer a low risk source of debt funding. Such a guarantee is of course, not available. In the case of a even a short period of high interest rates, it actually brings foward the cost penalty, and literally defeats a substantial part of the purpose of issuing the bond.

4) More fundamentally, why would such an approach to financing long term debt pass muster in a rational DMO? If we think about the principles of debt, it allows Government to offer risk free investment and defers major Government costs far into the future, funded by current interest rates. Historically, the British Treasury and BofE, when Britain was the world’s dominant financial force, issued ‘perpetuals’; debt with no capital repayment date at all. This worked for investors at the time, because there is a secondary market in bonds, where they can buy or sell their bonds (at a dscount to par). Perpetuals were eliminated only a few years ago. Indexed-linked accounts for only 22% of Debt (67% in short/medium/long term conventional gilts, and the rest in TBs, NS&I etc). It should be noted that from 2018 the DMO acknowledged a need to reduce its inflation “risk exposure” in index-linked bonds (DMO Report 2022-23; 2.22, p.7); only effectively to reverse that (2.23, p.7): “as a means of reducing its inflation exposure in the debt portfolio”. Make of that what you will.

I am struggling to see how bringing forward what is ‘de facto’ a very substantial capital repayment on an 18-year bond to today makes any sense, and does not in effect defeat a large part of the purpose in issuing a term, interest-bearing bond in the first place. Bonds are how Governments provide the overarching management of the time value of the money sovereign government issues.

Re 1) the ONS have commented, but the commentary is itself opaque. My correspondence on this with them is continuing. I am awaiting a reply from August.

2) Agreed: however looked at the treatment makes no sense at all

3) It is claimed this treatment is based on EU rules in turn laid down by the UN in 2008. I suggest that the guidance there is not as dogmatic as the treatment used.

4) There appears no rationalioty on any of the issues surrounding debt. You’d think it was deliberate

On 3) and the EU/UN guidance, if that was the key policy factor, I then struggle to see the attraction in using index-linked bonds under any circumstances; unless you believe you have ’20/20′ foresight and inflation will never be more than trivial over the life of the bond; which, of course quite obviously nobody possesses.

See Andrew’s comment

Can you provide a link to the EU or UN requirements? Is it this? The UN “System of National Accounts 2008”?

https://unstats.un.org/unsd/nationalaccount/docs/SNA2008.pdf

See paragraph 17.277: “When the amount to be paid at maturity is index-linked, the calculation of interest accruals becomes uncertain because the redemption value is unknown; in some cases the maturity time may be several years in the future. Two approaches can be followed to determine the interest accrual in each accounting period.

a. Interest accruing in an accounting period due to the indexation of the amount to be paid at maturity may be calculated as the change in the value of this amount outstanding between the end and beginning of the accounting period due to the movement in the relevant index.”

It seems odd to introduce (in effect) a form of “fair value” or “mark to market” for instruments that may continue for many years to redemption, especially when government accounts are usually done on a cash basis or an accruals basis.

The previous UN guidance (System of National Accounts 1993) was this:

https://unstats.un.org/unsd/nationalaccount/docs/1993sna.pdf

It said at paragraph 7.104: “When the value of the principal is index linked, the difference between the eventual redemption price and the issue price is treated as interest accruing *over the life of the asset* in the same way as for a security whose redemption price is fixed in advance.” [emphasis added: “over the life of the asset” suggests accruals, but it goes on to say:] “In practice, the change in the value of the principal outstanding between the beginning and end of a particular accounting period due to the movement in the relevant index may be treated as interest accruing in that period, in addition to any interest due for

payment in that period.”

Why?

The cash basis is very simple – cash is king – but is often a stupid thing to do because the cashflows can be very lumpy (you may already know that the cash you get today has to be paid out tomorrow). Booking amounts that are not paid for years – such as the inflated amount due on redemption – goes against that. The way to do that properly is to accrue over the term. The volatility of mark-to-market is just the sort of thing you don’t want to introduce in government accounts, for amounts that span many years.

The ONS’s July 2022 methodology note recognises that accrual over the term is correct with respect to premium on issue: why not for the inflated amount due on redemption?

https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/governmentpublicsectorandtaxes/publicsectorfinance/methodologies/thecalculationofinterestpayableongovernmentgilts

You have found what I have quoted to the ONS…

Thanks to Andrew for the links, and for the analysis. The ONS examples are helpful. First example in the ONS methodology paper is for a simple, pro forma twelve month Gilt. The accrual (2% inflation on 3% coupon) is very neat, because the redemption value is known, so the accrual smooths the interest costs and redemption uplift costs over the twelve months; with very small adjustments in monthly costs (<1%), save for month one. It is so neat, it really offers us nothing that reflects the real problems (unless perhaps an indexed TB? Not sure there are any).

Unfortunately I do not seem able to download the 5-year example offered (xls) – perhaps Andrew or someone else has done so, and can help here; but in any case the critical factor, I would surmise is how anyone could reliably forecast the final redemption value of the index-linked principal, possibly two decades ahead, until the principal is due.

The chosen examples are too short and over simplified

Hi Richard,

Thanks to Andrew for actually quoting the System of National Accounts 2008 – but the UK actually follows the European version of the SNA – the European System of Accounts 2010 (predating Brexit of course), for compiling National Accounts (GDP etc) and the Public Sector Finances, and then this guidance is supplemented by the guidance in the accompanying Manual on Government Deficit and Debt 2019 Edition (MGDD).

Rightly or wrongly, the guidance on recording interest on index linked securities, when the index is a general price index like RPI or CPI is clearly set out in paragraph 4.46 (c) (1) which states:

“(1) the amounts of the coupon payments and/or the principal outstanding are linked to a general price index. The change in the value of the principal outstanding between the beginning and the end of a particular accounting period due to the movement in the relevant index is treated as interest accruing in that period, in addition to any interest due for payment in that period;”

There is a longer explanation in MGDD section 2.4.3.11 paragraphs 38-45 which includes a kind of helpful mathematical example as well (though it unhelpfully muddies the waters by adding movements in the market price of the bonds as well)

I think, following this guidance, the ONS is right to record the uplift in principal due to the performance of CPI in a given year as an interest expense in that period.

I’ve weighed in on this before of course, and I understand that Richard disagrees with this, but ONS are genuinely just following the recording rules here, and other countries with index linked bonds in the EU also follow these rules – and then outside the EU, where countries issue index linked bonds, they would be guided by the IMF to follow essentially identical guidance in the Government Finance Statistics Manual 2014 paragraph 6.77.

From a personal point of view, having worked in this area for 13 years now, I don’t have the same issue that you have with this. Unless their are periods of deflation, the costs of redeeming an index linked bond will rise each year, and this rise gets added to the outstanding debt each year, and we record that rise as interest in that period.

Your proposed approach, for me, breaks the accrual principal – we record transactions when the economic event takes place, and the uplift to the amount owed in principal because of, say 8% inflation in 2022 occurs in 2022 and should be recorded in 2022. I don;t see the logic of recording interest in future periods due to movements in the index in 2022. To provide an extreme example – if the index increases by 8% in this year, then stays perfectly flat for the next 10 years, under the approach in the manuals we’d record the 8% interest now. In your approach that interest would spread over the remaining life of the bond, even when the index is unchanged and there is no change in the amount to be repaid at redemption. That feels wrong to me.

So again, I’d just like to note that while you and others disagree with this treatment, and have different views on the correct time of recording (you agree in principle that the eventual increase in principal to be repaid on redemption is interest on the amount originally advanced) it would be helpful if you could recognize that the problem here is not the ONS, or for that matter Treasury and the OBR, but the international organizations and their standard setting committees that have directed that index linked bonds be recorded this way.

Phil

I am aware of your expertise, and respect it, but you ate relying on three things here

One is the rules say this is right. And they are, a# you note, U.K. rules, and they could be wrong. They can certainly be changed. That is the business of government.

Second, you assume the UN’s flexibility no longer exists, but I question that, and the EU rules definitely need not apply, so this is a UK choice.

Third, as we both know, there are many measures of national debt, so an IMF compliant version can be offered (as a Maastricht one still is) but not be used fur decision making purposes. I think you would agree.

Fourth, accruals requires substance not form to be reflected in accounting, so the charge must be accrued over the life of the bond. Recognising the cost in full when no payment is due is the exact opposite of accruals in this case.

So, I regret I do not agree this time. This is deeply misleading accounting and there is no need for the ONS to use it

A fine explanation.

But the Tories don’t “do” explanations, they spout nonesense such as “maxed out credit card”, which has traction with Uk serfs.

An American politico once observed “when you are explaining you are losing”. Which begs the question: how to couple a snappy slogan with a more extended explanation.

If the UK did have a credit card, it would be a palladium card with no limit, issued by and backed by the Bank of England.

Which might lead UK serfs to ask the question: so how does that work? (explanation then follows).

If the tories insist on using the idiotic “credit card” metaphor, perhaps there is a way to have them hoist with their own petard, as it were.

Just an idea – how to change perceptions.

Agreed

Mike,

We do indeed “snappy” response to the same tired old mantras about maxing out credit cards,or there being no magic money tree, and the ultra stupid wailing of “Where is the money coming from to pay for it?”

I usually tell folk asking me such questions that the money will come from the central bank, end of. That the central bank hasn’t got a safe with money or gold in it, nor does it go looking down the back of the sofa for some loose change. Nor does it have a credit card….it doesn’t need one. The money is created by computer by simply tapping in some numbers into a computer. Thats it, so we can really do this very easily, allowing us all to get on with getting this country back to productive work, rather than having an entirely avoidable self-inflicted recession.

“When you are explaining you are losing”.

Apparently, this statement is attributed to the notorious Hollywood B actor Ronald Reagan.

The same Ronald Reagan who ‘explained’ things from cigarettes to pocket radios to his fellow Americans in adverts.

The same Reagan – whom I understand – also recorded an EP about the threat from socialised medicine in order to ‘explain’ to his fellow Americans how it was ‘good’ to pay for your healthcare. An EP that was widely distributed throughout America.

It’s so typical then isn’t it how the Neo-liberals then seek to deny anyone else the right to ‘explain’ things as they have done and benefitted from by coming up with a load of guff.

Let’s not listen to Ron, eh? He was bought out time and time again by his employers.

Let’s DO keep trying to explain and not fall for his half-baked American horse shit.

I agree with the idea of turning the “credit card” metaphor against the Tories, and might have a couple of suggestions for that.

The first would be to ask whoever is using the Credit Card metaphor on the day: “Can you state what the Government’s current credit limit is at the moment? How was that calculated? What factors have contributed to it, and can they be changed?”. When the opponent fumbles on that question, you can then use the opportunity to say that, just as banks assess people for a wide variety of factors (e.g. monthly income, creditworthiness, employment status, residential status, etc.), a government’s credit limit depends on the real resources that it can command, such as number of people employed/unemployed, raw materials, etc. (adjust to make it more in line with what MMT describes as the real limits to government spending).

You can then follow up with saying that the government’s true “credit card limit” will be whatever it needs to spend to guarantee the full utilization of resources in our country (full employment), while keeping inflation under control.

This is a draft idea, and I’m sure everyone else might find a way to optimize it, but basically, what I’m trying to do here is, instead of saying that the “credit card” metaphor is wrong and that there is no financial limit to government spending (which will guarantee trolls coming out with “hyperinflation” accusations), why not manipulate the metaphor to say “it is correct, but the true limit is whatever is needed to guarantee full employment, whatever that value is in a given year” (which is more in line with what MMT says are the true government spending limits).

Then again, there might be a better way of putting this. Any suggestions?

This is a response to Pilgrim & his very fair points.

We are in a propaganda war. You, I and many others that contribute BTL to this blog are aware of the falsities put forward.

Many are not.

I submit that we need “handles” to win the propaganda war.

“Maxed out credit card” is a negative handle and would get the response – “oh dear – does this mean gov spending cuts?” etc

“palladium card with no limit and backed by the BoE” begs the question – so why is the gov not spending? or “erm..how does that work”

In an ideal world people would be educated at secondary school on gov finance. They ain’t with the results that you would expect.

So I submit that we need responses that are positive & get people questioning. I have attempted (perhaps poorly) to offer one.

I encourage those contrubuting on this blog to make other proposals that they think might get traction with people.

Thinking about it

Describing orthodox economics as flat earth economics is a good start.

Mr Parr,

Well observed. The Conservatives have triumphed on sound-bites: ‘Labour isn’t working’; ‘Get Brexit Done’; ‘Levelling Up’. Notice that you do not necessarily even need to succeed, or DO anything that works, all you need is the sound-bite. The Devil, they say, has all the best tunes.

I suspect with those last (‘Get Brexit done’, ‘levelling up’ etc) we’re straying into the management of truth perception. We’re programmed to perceive repetition as truth so when we see politicians taking every opportunity to repeat a simple memorable slogan we should be aware they’re trying to manipulate our understanding of reality more than anything else. Illusory truth, it’s known as. “People tend to perceive claims as truer if they have been exposed to them before. This is known as the illusory truth effect, and it helps explain why advertisements and propaganda work, and also why people believe fake news to be true” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8116821/

I made this suggestion on your twitter feed.

Assume that the working economy will grow approximately in line with inflation. If it does, it will be as easy to pay off the bond in 2040 as it is today. The ratio of the debt to the money available to pay it off will be the same.

Of course if Liz Truss was right and we had Growth! Growth! Growth!, it would be easier to pay it off.

However, an implicit assumption is being made that this government will shrink the working economy by 10%, making it harder to pay the debt off.

Sadly, the latter may be the more plausible assumption.

Richard

I just dont get this

{ 1 } if the Govt has taken £540 billion savings off the private sector it must have spent/ invested it & then the multiplier effect will jump in & UK will be better off to repay the investment when the time comes

{ 2 } why do we need to pay interest when we can create our own money ?

{ 3 } Sunak reported we have to keep the financial markets happy/ I thought with brexit we were all sovereign now ? How near is the City of London to the Tower of London ?

I) True

2) I will cover soon

3) He is serving his masters

The current method of accounting is absurd. I won’t repeat my (moderately) detailed points made previously when you have tackled this issue on the blog but I think the simplest way for a lay person to understand the absurdity is to think about how the owners of Index Linked gilts account for them.

For every gilt sold there is a buyer; for every payment made by the government there is an investor that receives it. The accounting of gilts for the government should be the mirror image of the accounting by investors. This MUST be true.

So, ask yourself what does the owner of an Index Linked gilt think their interest income is? Whatever you come up with then this must be the interest expense incurred by the government.

If the real coupon is 1% and the (uplifted) face value is £100 then the interest is £1 for the year. If inflation for the next year is 10% then the interest will be 1% on the new uplifted face value (£110) or £1.10. Ie. interest payments have risen by 10%. No investor would consider the uplift to £110 as interest.

Of course, that uplift matters to the investor… but it is not interest.

An analogy is if you own a house worth £200,000 and rent it out for £5,000 a year. If the value of the house increases to £220,000 what is your rental income? – still £2,000. You would never consider the £20,000 increase in price as rental income… although you might think that you could raise the rent next year to £5,500.

Finally, on a separate note, we should also remember that government revenues are inflation linked so the increase in interest payments that does occur (but at nothing like the rate the ONS suggests) is more than covered by increasing tax revenues.

Thanks…

The last point is especially important

It would be interesting to see a govt minister respond to such points in an interview. I suspect they would just throw out whatever scripted response they could recall.

Even more interesting – would likes of BBC, ITV, Sky etc. ever ask such questions?

Craig

Clive (if I may),

“[W]e should also remember that government revenues are inflation linked”.

Goven the dangerous volatility of unknown future inflation, if you have a revenue inflation advantage (compounded by the benefits in the reduced value of deferred bond capital repayments on conventional gilts); why would you increase your inflation risk exposure by index-linking the bonds you issue?

In the “big picture” both revenues and expenses are index linked. VAT is a fixed percentage of price, benefits are (sort of) inflation linked and wages (in the long run) should exceed inflation only by productivity gains. However, it is quite a lot more complicated and to some extent impossible to know how things will evolve. For example, I suspect this current bout of inflation is not leading to much higher revenues because food and energy do not attract 20% VAT and wages are lagging prices – but on a 30 to 50 year view it is not a bad guess.

Up to the 1990s the UK was the only major issuer of inflation linked bonds and the motivation was to –

First, make a statement that we were serious about getting inflation under control (as the cost of I/L gilts would be less that conventional gilts if inflation was low). Second, to meet demand from Pension Funds (and other liability matching investors).

In the early 1990s, New Zealand undertook a massive de-regulation and opening of its economy with the abolishment of agricultural subsidies and the RBNZ (Reserve Bank of New Zealand) did some interesting work on asset/liability matching to the NZ government bond portfolio. It looked at the mix of local currency and foreign currency debt, the maturity profile of that debt and inflation linked versus conventional debt. The idea being to model the present value of all government assets and liabilities and construct a debt portfolio that minimised the volatility of the difference between assets and liabilities under a Monte Carlo simulation.

Now, how realistic this process was/is is up for debate but what is true is that in almost all circumstances you want some inflation linked securities in the debt portfolio and since then the US and Europe have developed those markets…. although the UK remains the leader in this field.

In conclusion, if Inflation linked bonds are “costing you more” then this extra cost is offset by rising income.

But, perhaps the most interesting aspect of this study was that it led to me and some colleagues becoming race horse owners !! The deep recession resulting from the deregulation meant that the racing industry was going to send most of its horses to the knacker’s yard, For the price of feed only we could have a horse. Needless to say, mine never won… but the RBNZ boys always seemed to have winners!

Clive,

Many thanks.

On Monte Carlo simulation you said: “Now, how realistic this process was/is is up for debate but what is true is that in almost all circumstances you want some inflation linked securities in the debt portfolio”.

First, Monte Carlo is a powerful tool with serious credentials, and I can claim no expertise. I think it began in physics, and when applied to the human behaviour domain, that instinctively sets off an alarm bell with me. I think I can see the attraction for bond prices, presumably because it can apply massive ‘what-if’ computational, iterative power to long histories of data and provide neat, intuitively elegant graphic answers. I think, however there could still be some disadvantages (theoretically, I understand it conflates variablity with uncertainty); which I surmise may mean, that if the major influence on prices is not already in the inputs, it may not adequately be recognised; maybe, like a mad Budget, or a war, or a pandemic, or a recession, or political turmoil, or irrationality, or climate change, or any unforseeable crisis (whether known unknown, or unknown unknown)? In short the interconnected complexity of unforseeable human behaviour producing outcomes neither plausibly predictable nor easily repeated……… (I acknowledge I am speculating here, but I think it worth raising some scepticism, whether right or wrong).

Second, I acknowledge your ‘inside track’ on Bond pricing, if I may jockey for a suitable metaphor, but I confess I still do not quite understand the value of index-linked bonds, at least given the (alleged), required accruals system; which offers a current demonstration that in adverse inflationary circumstances, the accrual system responds to the crisis by compounding the interest costs (on 22% of debt, worse if we had moved further down that track – I am not even clear whether the cost predicament is not worse by luck or circumstance). It seems to me its capacity to drag forward in time substantial costs the bonds are issued in order to defer is frankly rather perverse. It may markedly reduce, if not quite defeat a significant alleged advantage of issuing an index-linked bond, and may put pressure on Government to alter its debt policy, with an adverse chain reaction through the economy. That doesn’t look very persuasive to me.

I am not persuaded of the need for ILBs, and never was

They have always seemed like a product for the benefit of the market, not the state

Apologies, but one other point I wish to make on the risks associated with index-linked bonds, this time from the Market’s Delphic Oracle, the OBR itself. The OBR ‘Fiscal Risks Report’ (2017), says this on the fiscal vulnerabilities associated with index-linked bonds: “The Government is still to some extent cushioned against interest rate movements by the long average maturity of outstanding gilts. But once the APF’s holdings are taken into account – which have swapped around a third of all fixed-coupon conventional gilts for floating rate central bank reserves – the true vulnerability to short-term interest rate movements is much greater. And with index-linked gilts now amounting to nearly 20 per cent of GDP, vulnerability to inflation risk has risen too. The public finances are also more vulnerable than they were pre-crisis to shocks to household incomes, because of the narrower tax base and higher marginal income tax rates.”. (OBR, Conclusions 10.19, pp.304-5).

By 2018 it was policy to reduce the risk presented by index linked bonds; but in 2022 they are 22%; and in the 2022-23 OBR Report, the reduction appears no longer to be policy. As the quotation reveals, it seems, for once the OBR’s concerns possessed an element of prescience.

They were right, for once

One point that I have mentioned before but cant get an answer to, is how much money did The Government actually get for its stock?

For every pound in my Building Society account I put a pound in, but Gilts are sold at auction so the Government may get more – or less than the face value of the stock sold.

So, it gets £1.20 (say) for a bond where it only has to pay back £1, how is that reflected in the accounting?

Usually less than par

Hang on… on what you are saying this year’s accounts should show that same portion of all past inflation adjustments to inflation linked gilts, shouldn;t they? And next year’s must do the same and so on…

How much do you think there has been of late?

You do know they had negative rates for a long time, don’t you?

I may be missing something here but what struck me immediately is that the interest is compound so it would be £3 billion x 18. I posted your blog and the comment came back that it is mortgaging our future and I wasn’t sure how to respond. The argument is that this is not just a one off but every year. Get the fundamental point but struggling with counter arguments. Just a simple retired chartered accountant who never needed to be involved in this stuff until the madness of late

It is, of course, £3 billion every year

That is what I am arguing for

I’ve had someone come back to me when arguing this point saying that there will be the same amount of bonds each year so it would be £54 billion each year. Is he right in his first point about £540 billion each year or is that where the argument is going wrong. Sorry to be a pain but really want to argue the toss with him

The £54bn will be paid once, in 2040 in my example

If there is 10% inflation in the next year (immensely unlikely) then £59.4 billion would eventually be paid.

But the reality is inflation never lasts and this episode won’t

Hi Richard

Very interesting thread. Thank you. My limited view of this is that the OBR are some kind of ‘honest brokers’ in all this.

If they can see this , as you assert, do they see it but not believe in it? What’s their motivation for not calling this kind of accountancy out or at least drawing attention to it, to illustrate that the governments ‘black hole’ is government-defined and not an economic necessity?

I do not see them as honest brokers

They are paid by the Treasury, sit in the Treasury and effectively report to the Treasury. I think they know where there bread is buttered, as shown by their always too optimistic forecasts fo the outcome of government policy

I confess I was a little surprised that the conventional response to the Truss-Kwarteng madness was to say; the lack of an OBR review was critically important in the ‘market’ negative response. I was trying to remember when the OBR last provided an accurate forecast on anything,, or even one that was usable. No soubt it was critically imprtant; but then we need to consider, why? We forget too easily that the markets themselves are irrational, and their credibility among insiders is merely conventional, and inherently unstable (the lesson from Minsky, surely). It is all a very sophisticated operation, but it is purely a social ‘ritual dance’ to establish the routine authority of form over substance in an area of life notable principally for the essential lack of intellectual rigour sustaining the edifice. If it were otherwise, we would not ‘crash’ so often, or be so ill-prepared every single time.

Agreed

Here’s Osborne’s speech where he announced the establishment of the OBR https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/speech-by-the-chancellor-of-the-exchequer-rt-hon-george-osborne-mp-on-the-obr-and-spending-announcements

A cynic might suggest they were set up for the specific purpose of legitimising his wholly economically illiterate forays into austerity, that they did what they were told then and do now, and are and have only ever been no more than theatre designed to impress the rubes.

Whilst accepting that GDP is not necessarily a good way to judge health is there a risk that savings from austerity and extra income from tax is likely to be nullified by the economy (GDP) shrinking?

More than nullified

It is obvious to me why this is being done – it’s simply disaster capitalism isn’t it, artificially creating a crisis to leverage in reductions in public services to leverage in more private sector rent seeking.

By turning those bonds into a debt, it makes everything worse. It’s the fiscal equivalent of the Beeching cuts to the railways – supply the worst rolling stock and locomotives, unworkable timetables and people will be happy to see the back of it.

In other words break it and anything goes. So now we can see the Neo-liberal plan to shut the door that 2008 and Covid opened up on how Government can print and spend money.

We are still heading at express speed to the Exploitation State if people did but realise it.

Great article thanks. It’s not just unforegivable, it’s absolutely criminal. The government in Westminster are paving the way for full privatisation of public services, (those that are still in public hands) and councils are next. Yes lets hope the Labour party start to really oppose the terrible, destructive, backward, cruel, immoral financial assault on the poorest and most vulnerable in the UK. I fear they will not do that and I fear for our young people, who will be tied to low paid jobs, with huge rents to pay, and a very low standard of living. An absolute disgrace. The UK government seem more like a mafia outfit, actually working against the welfare of the people (who pay their very generous wages) for self interest, and to line their pals’ pockets.

They are putting the boot in when people are down, while blaming the people for being poor, for struggling to pay bills, and for many, struggling to put food on the table for their children. If that’s not a crime I don’t know what is.

It reminds me more of the Fall of Rome than simple criminal enterprise, everyone in authority bagging whatever they can for themselves before the Fall. Economist Michael Hudson reminds us ominously ours is unusual in civilisations in that it has no Jubilees, no resets, and so no routine time of renewal. Long Covid stalks the land, changing the balance between those able to participate and those unable but still deserving of life and needing to be provided for. None seems to be planned nor even contemplated. Collapse of some sort will be along really quite soon then, I think, and I’m trying to get myself in the best shape I can by way of preparation.

Richard,

You are making a fundamental error in your argument. You state:

“Right now the government charges the whole of this £54bn as an expense in the current year. It just increases the deficit and debt by this amount at this moment. This makes no sense at all.”

“Firstly, this accounting assumes that the £54bn is all due for payment now. But that is not true. On average it is due for payment in 2040. And for accounting purposes money due in 2040 does not have the same value as money due now.”

If, as in your example, the inflation uplift is indeed 10% the the nominal or face value of those bonds does increase by 10%. You then claim that the redemption value of the bonds in now £540bn + £54bn in 2040. Then you have discounted them from 2040 using the £594bn total.

This is a huge mistake. You have forgotten that here will be an inflation adjustment (most likely an uplift) for every year between now and 2040, so the redemption value of those bonds will not be £594bn, it will be significantly more.

If you applied annual inflation uplifts and only then discounted your answer would be valid, but as it is, it is not.

As an example, if you assume 2% inflation every year thereafter, the inflation redemption value of £594bn of bonds would be £832bn, which is the figure you can discount from.

It is also worth noting that the government splits its debt into component parts – redemption and coupons for the purposes of reporting.

They do this for a number of reasons, but this means that when looking at the reported amount of government debt you can simply take the nominal value of nominal bonds issued and the inflated nominal of inflation linked bonds. This has the advantage that no discounting is necessary.

One of the (many) reasons for doing this is it means you can separate the redemption from coupons, which you would not otherwise be able to do given the large array of bond coupon rates that exist, and to properly “price” a bond you need to take both into account (a 10y bonds with 1% coupon will have a very different price to a 10y bond with 5% coupon).

As such, the crux of your argument is wholly incorrect. The national debt has indeed increased by £54bn, as inflation linked bonds redemption values have increased that much in present value terms. If inflation is 5% next year, for example, then in future value terms it would increase by 5% which you could then discount back by 1y interest rates (call it 3.5%) to give a present value uplift of only 1.5% in real terms, but given the current 10% uplift is now historical, your argument simply is incorrect.

I do, of course disagree.

What the ONS is doing is neither cash or accruals accounting, which is amongst the many flaws in the system used.

If we do cash flow we get an exceptionally lumpy payment on redemption. I made a provision for redemption (an acceptable accruals concept widely used in financial reporting) to allow for this. What is your objection?

Alternatively, we could do a true accrual, apportioning the cost of the bond (as we know it) over its life. And let’s be clear, it is chosen to have a long life fir a reason, meaning this is necessary. I have offered a simplified approximation to that. I could complicate it, of course, but accruals would not do what you suggest and the ONS do.

Or we could do mark to market and if the government actively repurchased its own index linked bonds that might make sense, but it doesn’t (almost no QE has used index linked bonds), so the argument makes little sense.

And you can’t argue deny has gone up by £54 billion. All you can say is it has gone up by that sum in 2040.

So, you could discount as you suggest. But, I would argue that for a currency issuer (which the government is) with an inherently index linked income steam discounting is not at a nominal interest rate. Your assumption of rising cost fails to reflect this.

So we come back to a capital sum which the current bond holder will consider an income return far in the future has to be accounted for, and (having allowed for inflation as the bond does) at current prices. So we get back to how do we at current prices provide for £54 billion? As Clive Parry notes, no bond holder will treat this as income as a whole now. So, my system provides for this appropriately on a provisioning basis.

I suggest I got this as right as anyone could.

And, what is more, I am generating decision useful information which the ONS is most definitely not

Whilst I agree the accounting is simplified, it is standard and accepted practice when accounting for government debt across the globe.

Given accounts are prepared annually, the simplification (of only considering redemption amounts) means that the data is easy to compare and is not subject to the vagaries of interest rates mark to market on the accounting date.

In answer to specific points you make:

“If we do cash flow we get an exceptionally lumpy payment on redemption.”

We do see lumpy payments on redemption. This is the reality. I am not sure what “provision” you have made for this.

“Alternatively, we could do a true accrual, apportioning the cost of the bond (as we know it) over its life.”

This is commonly known as mark to market. We don’t need to simplify something that already exists. It does mean though that redemption and coupons need to be considered together, and cannot be separated, as I already mentioned.

“Or we could do mark to market and if the government actively repurchased its own index linked bonds”

Different arms of government use different accounting standards. Whole of government accounts use the method above, the BoE APF uses MtM, for example.

“And you can’t argue deny has gone up by £54 billion. All you can say is it has gone up by that sum in 2040.”

This is what you have totally wrong. Indeed, debt has gone up by £54bn, but that is the 2023 nominal increase, not the increase to 2040. You are either ignoring any future inflation uplift or simply don’t understand the subject matter. The 2040 redemption value of an inflation linked bond is unknown, as opposed to nominal bonds which always mature at face value.

“So, you could discount as you suggest.”

Only if you take thhe fully inflation uplift to 2040. As I pointed out, this would be a far higher value – £832bn if you assume only 2% inflation out to 2040.

“discounting is not at a nominal interest rate.”

Why would it not be? What rate would you use?

“So we get back to how do we at current prices provide for £54 billion? ”

The £54bn inflation uplift has already happened. It IS at current prices. Nothing more needs to be done. If you want to work out the value over the life of the bond, that is different, but the £54bn is already set in stone.

“I suggest I got this as right as anyone could. ”

No, you have got it completely wrong.

“I am generating decision useful information”

I am not sure how incorrectly pricing and accounting for inflation linked bonds helps make decisions. At least with ONS data you can see comparable redemption value information and comparable coupon/interest payment information. Simplified marginally, but acceptable. Your value is utterly useless as simply it is not correct.

How much can be got wrong in a single comment?

You start by saying accounts are prepared annually. Wrong, this data is monthly. Nor does it form part of a set of accounts. It couldn’t, because it does not use double entry or comply with it.

So, the reason for this data is not to provide market information on value of debt (and if you knew anything about the national debt you would know there are already multiple such measures, and no single one is right). It is to provide decision useful information for government. That is the context in which I have viewed it.

So let’s do a simple comparison. Is it more useful to say in the scenario outlined “You owe £54bn and must find it now” or to say “You owe £54bn in 18 years: start making a provision now to reflect the payment due when it is payable”? Clearly it is the latter. That directs decision making as required. The former only induces unnecessary austerity.

And the ONS could produce data as I suggest and still produce the required UN/EU data for supposed international comparison, although as the standards in question are hopeless on QE the comparison is anyway meaningless.

But is what I suggest the most useful decision informing accounting that also reflects a) substance of over form and b) accruals? Yes it is.

So please do not waste my time again. It is very clear you do not know what you are talking about, as I note from the first comment onwards, and your posting pattern strongly suggests trolling as well.

Ernest,

Interesting. You are treating this as if it was an ordinary set of corporate accounts. It clearly isn’t. I think Richard is better able forensically to tackle that in detail than me.

Your best defence is MTM. Notably traders (correct me if I am wrong, but here is my understanding), as they do; in the US, since 1997 MTM traders use MTM on the last day of the trading year to change the tax status of their earnings from capital gains/losses to ordinary income/losses. The following day, the position is reversed (in the US MTM traders are exempt from the ‘no wash’ rule). You will object to my use of that ‘information’ here. My point is, MTM traders can presumably distinguish between capital and revenue perfectly well; the best that can be said is MTM makes the whole distinction porous, notably for the expert users, and for tax purposes. This rather chimes with Clive Parry’s separate point on the revenue/capital distinction . from investors (who are not traders).

There is a real problem here with index linked bonds; from the accounting that clearly is all form and and mechanical process, but lacks intellectual rigour, to the very real fiscal risks of Governments using index linked bonds (see OBR Fiscal Risks Report, 2017).

Thanks

Ernest,

Suppose for a moment your interpretation is right. All that demonstrates is that it is an appalling misjudgement to issue any index-linked bonds, since it effectively undermines the whole purpose of Government bonds; providing the best investment security to investors by using the advantages of the natural time value of money for the benefit of the sovereign currency issuer. If you did want to advance payment by a significant amount (only in very special inflationary of crisis circumstances), then QE provides the clean soultion. What you cannot deny? What we have is a mess.

I read Ernest’s post with interest and have to just check something.

Richard, let’s take an example.

Let’s say that in 2021 the government had £500bn of inflation linked bonds in 2021 terms.

Then let’s say inflation 21/22 is 10%. So I hope we can agree that the 2022 value in 2022 terms in going to be £550bn.

Let’s now say for arguments sake that inflation 22/23 is also 10%. What do you think the value of those inflation linked bonds is going to be in 2023?

I do not agree the value is £550bn. It glaringly obviously is not for reasons I have explained. So your question is inappropriately framed.

What on earth are you talking about?

All I have done is round the numbers to simplify the example and used £500bn instead of £540bn.

Which means the following year after inflation the increase in £50bn instead of £54bn, making the total £550bn instead of £594bn.

What I am asking is what is the number the following year, when inflation is 10% again.

Because if from year 1 to year 2, if inflation is 10% and we see a 10% increase in the debt, surely the same will happen again from year 2 to year 3 if we again have 10% inflation. What do you say the increase and the total debt will be at the end of year three?

And, as I have explained in my thread, and in answers, the liability is not £550bn.

It may be in 18 years but there is no way it can or should be recorded as that now, because that is false accounting, which is my whole point, I have explained why.

Now, read the article, understand the issues and stop wasting my time please

OK, in that case you simply don’t understand inflation linked bonds. The whole point is that the nominal value increases at the same pace as inflation.

What you are saying is nonsense. That the increase in 1 years worth of inflation is spread out over the life of the bond. And while you are at it any future inflation is ignored.

Fortunately, the DMO themselves provide a helpful calculator to work out inflation linked bond redemptions:

https://www.dmo.gov.uk/data/pdfdatareport?reportCode=D9C

Or you could have read the DMO’s Private Investors Guide to Gilts and the example they give on page 7:

https://www.dmo.gov.uk/media/x3snorxn/pig201204.pdf

Low and behold, they get inflated every year. So what Ernest said above is right – to discount them as you have done you have to inflate the bonds in your example to 2040, then discount back. But you’ve only inflated them for 1 year.

You’ve got it totally wrong.

I actually inflated them every year fot the remainder of their life.

If you don’t read the question you get the wrong answer

You did not read what I wrote

And the nominal value at a point in time is utterly irrelevant. It will never be paid and is only a factor in market value, which will most definitely include serious discounting

I think you really are getting this wrong

Where did you inflate them every year? Can’t see it in the calculations. You’ve only done it for one year – inflating the bonds from £540bn by 10%.

Then ignored the rest of the bonds life and claimed that was the redemption value in 2040, then discounted from there.

Which is simply wrong.

The nominal value of inflation linked bonds is quite important really as it tells you the current value of that debt.

You could have inflated the bonds for their entire life and then discounted, but you didn’t. So either way you’ve got it completely wrong. I don’t know why you are trying to claim you haven’t as literally everyone who knows how linkers actually work would tell you the same thing.

Including the DMO as mentioned above.

Did I refer to any assumption on future inflation? No. Why? I assumed it was a singular event fir ease. You made the rest up. I suggest you stop trolling.

Following Clive Parry’s point, if investors want to know the current value of their stock, they can look it up, and sell or buy. Today, Treasury 0.125% maturing 10/08/2041: price 103.750. The price on 10th August, 2041? Either it is priced in to today’s price (time value adjusted if you think much of that proposition) or, more realistically? Who knows unless you have insight into inflation volatility for who-knows-what-reason 2022-2041. Some of us won’t even be around.

Government bonds are the essence of ‘safe asset theory’. Index linked bonds, I am increasingly suspicious, are market efforts (quite possible unconscious, but no less dangerous for that) to reduce the bond market to just an other risk loaded market for traders, dealers and hedgers to play with and extract big profits, by turning them toawrd exploitable high risk-return opportunities. The accountancy, as always, just falls in line.

I think your second para very true

Yes, the face value of the 500bn will become 550bn. But (assuming an average real coupon of 1%) the interest paid will be 5.5bn at the end of the year (versus 5bn last year). Next year, if inflation is zero, the interest paid will be 5.5bn and the face value of the debt will still be 550bn.

The problem with including the 50bn “uplift” as interest is a) no investor would see it that way and b) in the minds of most people ‘interest’ is an ongoing annual expense that will be repeated until redemption….. and this is not. It will decline as inflation declines.

What people want to know is “how much do I owe?” (amount of debt outstanding) and “what do I have to pay each year to service it?” (interest).

Interest is easy – just add up the coupons paid out. (Give/take the minor discount to face vale that gilts are usually auctioned at, this is accurate)

Amount of debt outstanding is also easy – just add up the market value of all gilts. I would then attribute any change to a) net gilt sales (issuance less redemption) which is roughly the budget deficit b) inflation uplift to the face amount of I/L gilts and c) changes to market value due to changes in market yields.

Nobody is trying to deny that inflation makes the face value of I/L debt go up…… but to inaccurately state that the interest burden has risen by 50bn with the implication that this higher number will be repeated…. and that this should inform tax/spending decisions is dishonest.

Agreed

And that was your 1,000th comment

[…] HomeNeo-Liberalism in the EUAusterityRichard Murphy – We’re going to have austerity on the basis of some very dubious accounting for the national debt […]

The credit card metaphor is terrible. It is OK to say that the government has no financial limits on spending along as you link it to the fact that it, at the same time, also has resource limitations that impact its spending as well as noting that it must take note of inflation. To say that the govt has no financial spending limits does not imply, and does not mean, that it has no limits at all.

I agree

And that is the MMT defence

Let’s pick a real example. https://www.reuters.com/markets/europe/uk-sells-new-2073-index-linked-gilt-with-record-low-volume-2021-11-23/

In November 2021, the UK issued £1.1 billion of an index-linked gilt maturing in March 2073.

This gilt bears interest at 0.125% pa.

Plus of course the indexed increase in the £1.1 billion principal each year, with (in effect) interest calculated on that inflated amount.

It was massively over-subscribed, and the investors paid around £3.9 billion – a premium of £2.8 billion on issue. A real yield of -2.3883%, (Yes, you read that right, over the 50+ year term, it has a negative return each year, before inflation.) Even on a straight -ine basis, that is a return on the principal of minus £54 million each year.

What is the cost of this bond to HM Treasury in the year to November 2022, if inflation is 10%?

* The principal repayment (in 2073) increases by 10% to £1.21 billion, so a “cost” of £110 million. You could recognise all of that £110m in 2022, or spread it over the next 51 years, at about £2.2 million per year.

* The actual interest would be (I think) 0.125% of that inflated principal, or about £1.5m.

* And the unwinding of the premium would be a large negative number – someone can help with the maths, but it must be in excess of minus £54 million. If you deflate the capital from £3.9 billion to £1.1 billion over 51 years (at 1/(1+0.023883) I think that is about minus £90 million in year one.

What assumptions are we making, if we allocate all of the cost of the inflationary increase in the principal to the year it occurs? What if inflation is zero, or 1%, or 2%, for the next 51 years?

Excellent

And no time to do the maths