HM Revenue & Customs is under fire from the Public Accounts Committee this morning, and rightly so. In a new report they say:

HMRC ignorance and inaction “rewarding the unscrupulous” and looks “soft on fraud”

In a report published today the Public Accounts Committee says “HMRC's unambitious plans” for recovering a total of £6 billion it estimates it spent incorrectly in COVID-19 support payments – whether through fraud or mistakes - could lead to “government writing off at least £4 billion” taxpayers' money. The PAC says this “risks rewarding the unscrupulous and sending a message that HMRC is soft on fraud”.

The Committee says “yet again customer service has collapsed and HMRC's recovery plans are not clear”, and it is extremely concerned about HMRC's capacity to clear backlogs while tackling the “avalanche of error and fraud it now faces on the COVID-19 schemes”.

The report describes a litany of longstanding PAC concerns in HMRC's fulfilment of its most basic remit of collecting tax owed including not responding adequately to tax avoidance schemes, failing on implementing or realising benefits from the ‘Making Tax Digital' and other long-term transformation ambitions and programmes, and being without “a convincing plan for restoring compliance activity back to pre-pandemic levels”.

The Committee also says HMRC simply doesn't know why the cost of key tax reliefs has increased, or how much of that is due to abuse.

I have a particular interest in this issue because of the work that I do on tax gaps and tax spillovers.

One of the more controversial inclusions in the tax spillover framework was an appraisal of jurisdictions' tax politics. This is a qualitative measure of the attitude of the political establishment within a jurisdiction towards its tax administration. Some have questioned whether this can be measured, but along with my co-author, Professor Andrew Baker of the University of Sheffield, I have suggested that in very many cases this measure is easy to appraise on the scale that we use. For example, it is easy to tell that there is a difference in the political attitude towards tax in Sweden and the Cayman Islands. As importantly, whether a jurisdiction, such as the UK, adequately funds its tax authority and simultaneously has an appropriate attitude towards tax transparency and tackling fraud is also something that is relatively straightforward to appraise.

The government objective with regards to funding HMRC has, for many years, been to cut its resources. It is treated as a cost centre, and not as a revenue generating activity, which is utterly bizarre.

Because the UK government is utterly indifferent to transparency, as indicated by the almost totally negligent management of Companies House by Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, which means that those wishing to undertake fraudulent activity can do so with almost total impunity, the chance of tax abuse in the country is very high indeed.

In the last week we have seen the Business Secretary claim that people in this country are not worried about fraud, presumably because he is not.

At the same time, HMRC publish a tax gap calculation which is not credible, firstly because no one should be marking their own work, and secondly because it always produces an almost identical figure, and has done for more than a decade, which leads me to doubt the credibility of any claim made. My own opinion, based on the VAT gap, is that the overall tax gap in the UK is more than double that suggested by HMRC.

The consequence of HMRC's management focus being on cost saving, and its indifference towards any other issue including customer service, collecting the right amount of tax, tackling fraud, closing the tax gap or anything else, is the that appropriately summarised by the Public Accounts Committee in its expressed concern over the out-of-control management of Research and Development tax relief. As the Committee notes:

HMRC is responsible for administering Corporation Tax research and development (R&D) reliefs, which support companies that work on innovative projects. There is a scheme for small and medium-sized enterprises, and a research and development expenditure credit scheme, mainly for larger companies. Both schemes are complex and open up opportunities for abuse

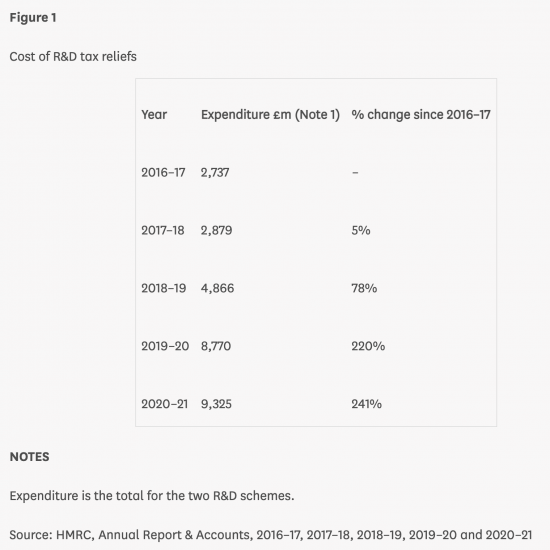

It would appear that these costs have escalated, dramatically, in a way that appears unrelated to the likely scale of research and development actually going on within the UK economy, as this table shows:

I have long suggested that the only increase in research and development that this relief has created has been amongst accountants working out how to re-categorise expenditure as research and development. The consequence, as noted, is that £9.3 billion has been spent on this relief in the last tax year, and HMRC do not know why, or whether value for money was secured. As a consequence of HMRC mismanagement of this issue we have a national insurance increase that will create hardship for millions instead (and for those of an MMT persuasion, the two can be related to each other as MMT suggests a government should have total revenue target as part of macroeconomic management).

I have noted the various recommendations that the Public Accounts Committee has made in its report. Each is appropriate, in its own context. The difficulty that I have with them is that none appears to be systemic. What is wrong with HMRC is its management culture, which is modelled on that of a public company, with a board that sets priorities as if it was managing its affairs to minimise cost, which it does without consideration of consequence.

What we need in the UK is not some minor shifting of priority within HMRC, but a new tax politics. That should be based, first of all on a proper understanding of the role of tax in society, which I suggest to be:

1) To ratify the value of the currency: this means that by demanding payment of tax in the currency it has to be used for transactions in a jurisdiction;

2) To reclaim the money the government has spent into the economy in fulfilment of its democratic mandate;

3) To redistribute income and wealth;

4) To reprice goods and services;

5) To raise democratic representation - people who pay tax vote;

6) To reorganise the economy i.e. fiscal policy.

Then we need to resource our tax authority to fulfil these goals on behalf of society in a way that imposes minimum cost upon taxpayers, but which maximises the collection of revenue really due to ensure that we operate an economy in which everyone plays on a level playing field to ensure that we provide equality of opportunity for all, whether in or out of business, and whoever they might be.

In turn, that will require a change in attitude from Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy towards the management Companies House, but it will require a reorientation of focus within HMRC towards fraud, large scale tax avoidance and abuse by advisors, which must be behind much of the growth in research and development claims.

All of this is, of course, possible, but it does require a government committed to achieving these goals. My question is a simple one. When will we have such a government?

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

When political parties live up to their names?

Time is well overdue for a root and branch reform of the tax system including

1) Pay a Universal basic income to every UK citizen

2) Remove all existing tax allowances (UBI more than compensates for personal allowance. Couples living together with 2x UBI benefit by more than marriage allowance, etc)

3) Replace NI with unified income tax rates (in bands) that apply to all income equally – pate, self-employed, property, investments, capital gains, etc.

Such wholesale change would vastly reduce the complexity and cost of of tax compliance, as well as reducing poverty, increasing incentives to work, and reducing inequality. With UBI instead of means testing the poor for benefits,

enforcement can focus on means testing the wealthy to catch more tax avoidance/evasion strategies.

While a support UBI in principle, I see some problems for it if it is not part of a package that includes rent controls and free or very cheap reliable public transport in order to address the very real differences in the cost of living in different parts of the country. I also don’t think it can replace all welfare benefits as some people suggest. There will still be some very sick or disabled people who will need extra support.