Bulb Energy failed yesterday, and reports suggest that to keep its 1.7 million supplied with power will require significant state financial support. I thought it appropriate to have a look at the accounts of the company to see if this could have been predicted. The short answer is that it was predictable.

In this post I will be referring to the accounts of two companies. They are Bulb Energy Ltd (Bulb) and its parent company Simple Energy Ltd (Simple). The links are to the files of both companies at Companies House, from where I obtained all the information that I will use.

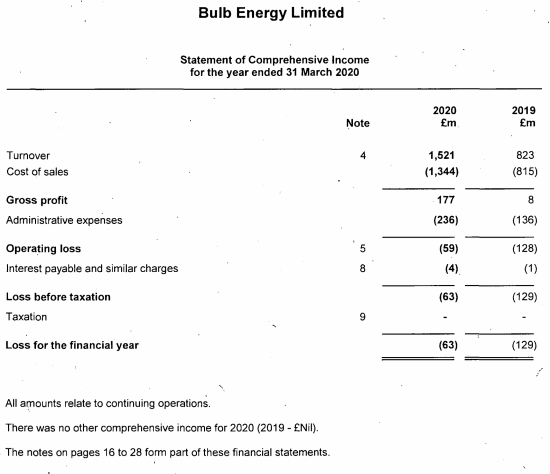

Bulb was a loss-making company in 2019 and 2020, as its income statement shows:

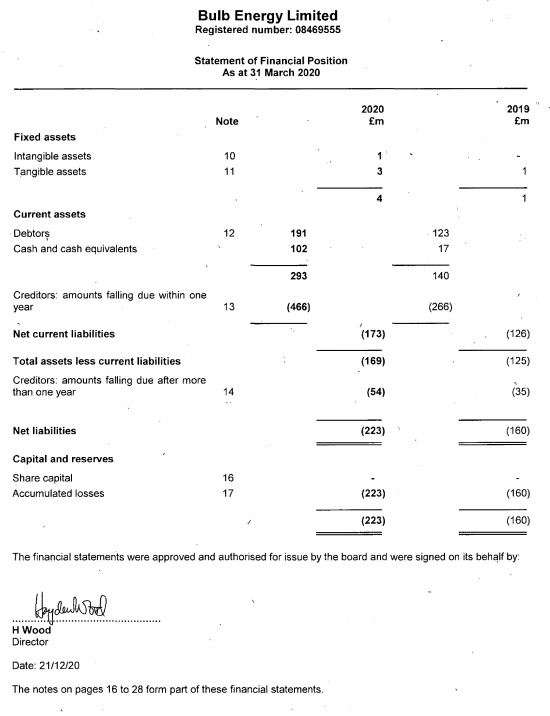

More worryingly, the balance sheet showed the company to have many more liabilities than assets, which is a fairly clear indicator of insolvency:

The company owed £223 million more than it had in assets. £173 million of the liabilities fell due in less than a year without assets to cover them.

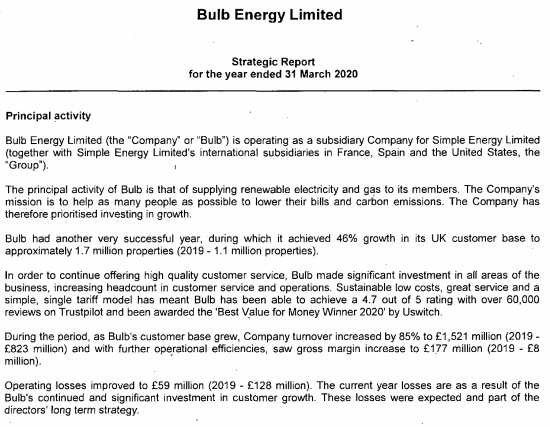

The directors were not worried though. They said in the directors' strategic report:

It is an interesting idea that a company might have a strategic goal of making a loss. I am also curious as to the claim that investment was made in all parts of the business when, as is apparent from the balance sheet, just £1 million of fixed assets were owned. This was a company that added no value by itself: everything it did was about trading at a profit margin. The only difficulty was, that margin was absent at the level required.

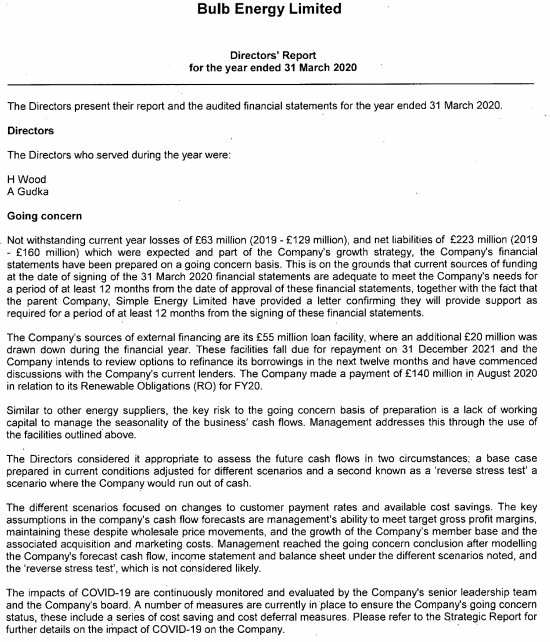

Having made such bullish claims, the directors had necessarily to consider whether the apparent insolvency shown by the balance sheet suggested that the company was not a going concern meaning it did not have the resources to continue to trade and settle its liabilities as they fell due. It had this to say on that issue in the directors' report:

For reasons that are not explained a loan facility of £55 million was deemed sufficient to cover the deficit of almost four times that sum.

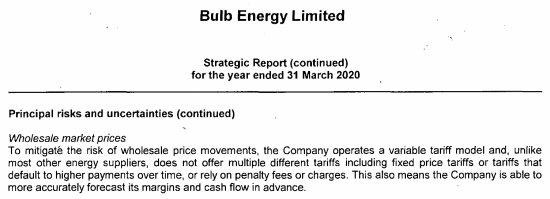

It was not as if the directors were unaware of the risk that they were taking. When discussing those risks they said:

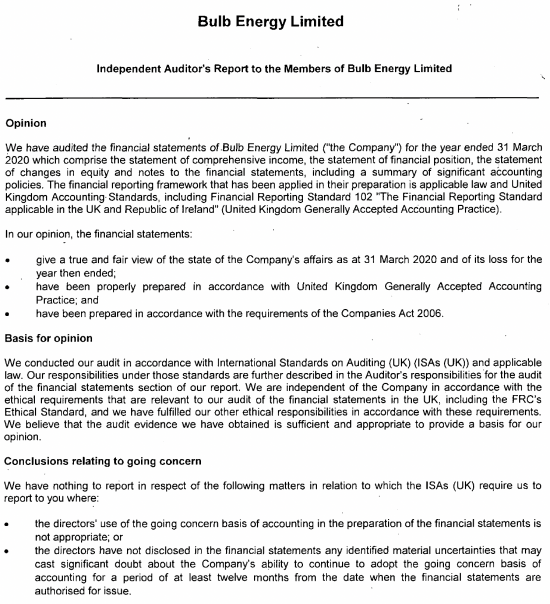

I am not suggesting that anyone should have foreseen the increase in wholesale fuel prices that have taken place since March 2020. I would, however, suggest that if the directors were aware of the significant risk to the company then they had a very obvious duty to model the possible consequences of substantial change in that price to determine whether this would have put the company at risk. What now appears certain is that their belief that the use of a variable price tariff would cover any risk without the apparent use of hedging appears to have been misplaced. It did, however, appear to keep the auditors satisfied. BDO LLP said in their audit report:

It is very apparent that BBO satisfied themselves that the company was a going concern. Despite that fact it has not lasted long enough to file its next due financial statements.

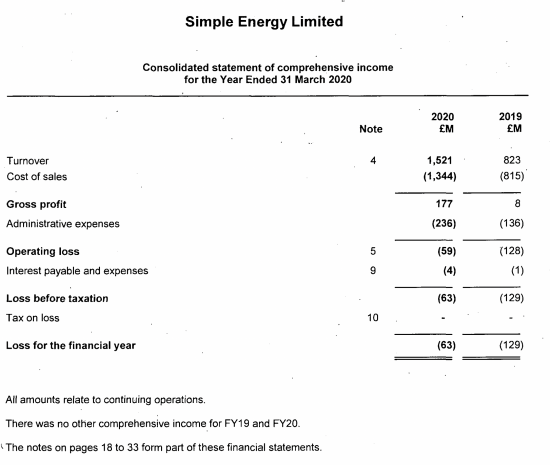

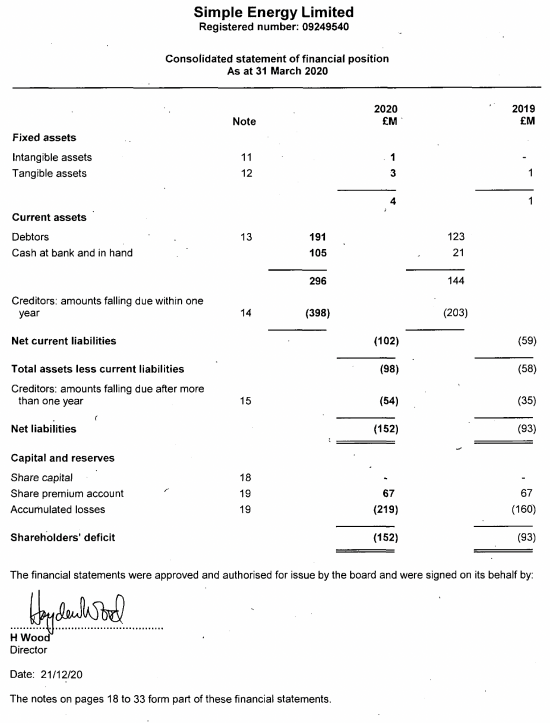

It is only fair to note that Bulb did, when making a statement that it was a going concern, suggest that it was also relying upon support from its parent company, Simple. For the record, this is Simple's income statement for the same period, followed by its balance sheet at the same date:

As is apparent the financial performance of the two companies are virtually identical: Simple is simply consolidating the results of Bulb. None of its other subsidiaries make any significant contribution to the financial results.

That said, the balance sheets are different. Simple has significantly more share capital than Bulb and for that reason appears to be running a lower overall deficit of assets than Bulb. Bulb suggest that this let Simple provide it with a financial guarantee. I admit to some doubt as to the basis on which that guarantee had value.

Simple says of its accounts being prepared on a going concern basis that:

In effect, the directors are saying three things. The first is that they could adjust prices quickly enough to cover any change in wholesale prices for energy. Second, they claim that their ability to meet gross profit margin goals apparently provided them with the ability to maintain themselves as a going concern even though that gross profit margin was insufficient to cover their ongoing costs. Third, they imply that continuing growth would address this last risk, meaning they dismiss the likelihood that they could run out of cash.

The auditors (BDO LLP, again) offered a similar comment on this issue in this company to that which they supplied for Bulb. They were as a consequence satisfied that the company was a going concern.

The reality is that the model used for these purposes was obviously wrong. It has transpired that the company could run out of cash, presumably implying that there was insufficient durability within the pricing model of the company to cover the volatility in energy markets and so provide continuing gross margins, irrespective of the ability to control costs. The company has failed as a result.

What is to be concluded from this? I suggest the following.

First, it has to be said that this company simply did not add value. It wheeled and sealed in the energy market, seeking an ever larger market share in what did already by March 2020 look to be a vain attempt to earn sufficient gross profit to cover costs that were disproportionate to the scale of activity, almost certainly because (as the directors imply in their reports) marketng was the focus of their attention, and any amount of money can be sunk into that activity.

Second, whatever risk appraisal was undertaken with regard to future cash flows of this company it now looks unlikely that they were sufficient. The assumption implicit in the directors' comments that there would always be an adequate time lag between moves in wholesale price and the ability to increase tariffs was clearly not true.

Third, the apparent indifference of the auditors to the going concern risk, given the fact that wholesale price changes were identified as a material cause of concern, will, I very strongly suspect, give rise to a referral in due course of BDO LLP for a thorough review of the adequacy of the audit that they undertook.

Fourth, as is so commonly the case, the narrow focus of this audit fail to take into consideration the interests of so many of the stakeholders of this company. The conventional focus was on a report to the shareholders as the whether the company in which they own shares could survive, or not, with the conclusion being drawn that this was possible. The risks to other stakeholders, including wholesale energy suppliers, employees, customers, regulators and the government, as well as society at large, do not appear to feature in the consideration given as to the consequences of the company being a going concern, or not. This only reveals the inadequacy of the U.K.'s financial reporting standards, which were used for the preparation of this report.

Fifth, this company does, then, appear to be added to the catalogue of audit failure which is now becoming so commonplace. I suspect that BDO will offer two defences. The first is that the regulator must have known of some of these issues. I also suspect that the regulator would deny this. The second is that last year's accounts were signed on the 21 December 2020, and maybe given that BDO must have had their audit well in progress by now it was their refusal to sign another audit report on a going concern basis that might have caused the current insolvency, but I am entirely speculating when saying that.

Some final comments are appropriate. First, as I have already suggested today, the reliance of so many UK households on such a peripheral company within the UK energy market, which had by itself literally no investment in energy production, is profoundly worrying and a systemic risk that surely should not have been permitted.

Nor, surely, should it have been allowed that a company with such a weak balance sheet, even before wholesale energy price volatility was apparent, should have been allowed to grow to have the number of account holders that this one did. In itself this appeared to be a crisis that was always in the making.

And, yet again, it has to be said that accounting, accounting standards, accounting regulators, auditors and audit regulation have failed with the tab being picked up by society at large.

There is a persistent thread that runs through these failures. That recurrent theme is a belief that markets can deliver better outcomes than any other supply mechanism. It is abundantly clear that this assumption is wrong, and not just with regard to energy, where Bulb is just the latest of many companies to fail, albeit that it is by some way the largest. That assumption also applies to the supplier of audit services. Whether the market can now be relied upon to really deliver audit services of the quality that society needs is a question that has to be asked however uncomfortable that might make my own profession and this government feel. It would appear that the time for radical reform has arrived.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

Did BDO do anything for the £279K fee? I wonder if this year they have done twice as much work – this year’s audit plus filling in all the paperwork they should have done last year.

How does a group that is insolvent by £152M get a clean audit report?

I’d like to see pay scales for the Directors.

Alarm bells ring for me when I read that the directors are: “…supplying renewable electricity and gas……. (??). Renewable gas? Is that a thing?

“And, yet again, it has to be said that accounting, accounting standards, accounting regulators, auditors and audit regulation have failed with the tab being picked up by society at large.”

“These losses were expected and part of the directors’ long term strategy”. Longterm strategy for what? Passing on the costs to society at large because the regulatory authorities allow them to do so ? Or did they really think they had a viable energy supply/charging business plan here ?

Is ‘Simple’ in any meaningful way a parent company ? It sounds reminiscent of the Enron scam. (?)

I have to agree with your concluding comment: “It would appear that the time for radical reform has arrived.”, but I don’t see it coming from the present government and I fear the Opposition if they ever get to the government benches will be fearful to tackle this.

The absence of any real alternate policies from the “Opposition” is rather telling. Currently the word Nationalisation is a dirty word. But isn’t a Green New Deal absolutely a function of energy providers being part of that investment. And how can this happen when the so called division into “competing” energy companies is simply ripping off at the behest of dud accounting!

Is it still a dirty word?

I fear so…..

yes agree

[…] have already analysed the last available accounts of Bulb. They are not pretty. But, to suggest that they required a capital injection of £1.7bn seems […]