Inflation is a concept most people are now unfamiliar with. Unless you were economically active 30 or more years ago you simply have not experienced anything but the mildly beneficial effects of very low levels of inflation. And now it is suggested that the issue is back on the economic agenda.

So let's be clear about what inflation is. Inflation is generally defined as a general increase in prices and a consequent fall in the purchasing value of money.

There are good reasons to question whether we have inflation on the basis of this description at present. Some big-ticket items are undoubtedly suffering inflation as a result of some supply chain shortages when there is excess demand post-Covid. Second-hand cars and some furniture have been examples of that. Food has also faced this issue, in part. Other price increases are external shocks. The increase in gas prices reflects this. So far these external shocks have not resulted in a general increase in prices: the fear is that they might.

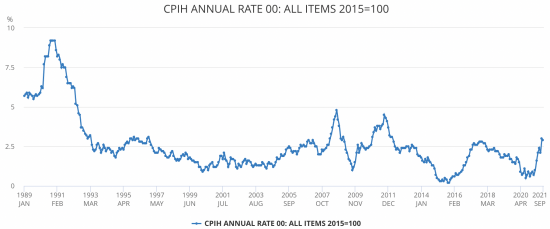

Bue before we get excited about this some data helps. This is UK inflation since 1989 when the measurement of inflation moved to the consumer prices index:

There are a number of things to note. The first is that on average inflation is below 2.5%. And when it has gone above that rate since 1993 the rate has always fallen pretty rapidly back to below that level.

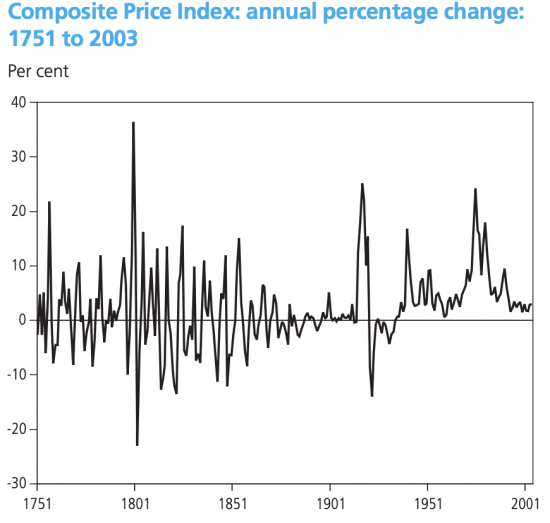

This is not an aberration. This is a chart of UK inflation since 1750:

As the evidence of the previous chart shows, the line continues almost flat after 2001. We have in that case had the longest period of price stability in UK history. But what is apparent is that whenever there has been an inflation hike there is always very soon afterwards a substantial fall. Too often that actually resulted in deflation - which discourages economic activity. Thankfully, we now avoid that. But there are three key issues to note, and I will concentrate on more recent history whilst nothing the longer trend.

First, the UK has never had hyperinflation, which is often thought to be 50% inflation a month. So any discussion of inflation of that sort is ridiculous in the context of the UK economy.

Second, the broad trend of inflation is towards stability.

Third, looking at the last century any significant inflation has only been associated with war or serious related shocks. The three major events are the first world war, the second world war and the 1973 oil price shock that came after the end of the gold standard. Anything else - such as that which related to the departure from the European Exchange Rate Mechanism in the late 1980s and early 1900s, came from the failure of government foreign policy.

The simple fact is that inflation does not happen for reasons resulting from UK domestic economic policy: they are foreign policy events. It could, of course, be said that Brexit is another example of that since the supply chain disruptions that are now contributing to price pressure are undoubtedly related to that. I do think there is logic to that claim. But it's also fair to say that the forecast inflation spike - at 5% - is very small by historic standards. What is more, just as all forecasts suggest, and as historic data agrees to always be the case, soon after that spike happens as a simple matter of fact that inflation will go away again. The way that inflation is calculated almost guarantees that.

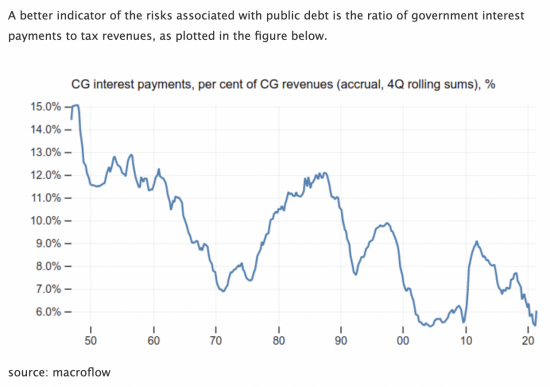

So we need to worry about inflation then? First, let's take the government's concern that this will increase its cost of paying interest on the national debt as a result of interest rises. Here Jo Michell has done some useful work. As he notes:

Note that we are at near enough record low levels of overall interest cost to the government.

As the also notes:

Interest payments on government debt have indeed risen recently. A spike in June triggered media articles about the highest interest payments on record. In context, such statistics are shown to be meaningless. Interest payment have risen to around 6% of taxation over a four quarter period, compared with all-time lows of about 5.3%. (Calculated on a 12 monthly basis this rises to around 6.5%). It is hard to see signs that the sky is falling.

And as he adds:

In fact, this indicator overstates current interest costs. This is because much of the interest paid by the Treasury is paid to the Bank of England which holds a substantial chunk (currently around 37%) of UK government debt as a result of QE (see chart below). Most of this interest is returned directly to the Treasury. Since the start of QE, this has saved the Treasury over £100bn in interest costs.

Even if interest rates go up there is actually no reason why interest costs on this quantity of debt owned by the government need go up: the Bank of England need not pay base rates on the central bank reserves accounts held by UK clearing banks with the Bank of England as a result of QE: the existing rate could be maintained if desired and there is literally nothing those banks could do about it. Why they need a windfall gain of billions from an interest rate rise is very hard to work out and anyone having the political courage to oppose them would seem to me to have an open political goal to aim at by opposing that benefit going to banks.

In other words, this need not have any significant impact on government spending, But, if it does, then the only impact it should have is in increasing the pay of civil servants and other public employees to protect them, as pensioners will be. Other benefits should obviously also rise as well. That would be right. Paying banks would not be. That apart there is no reason for inflation to have an impact at this moment.

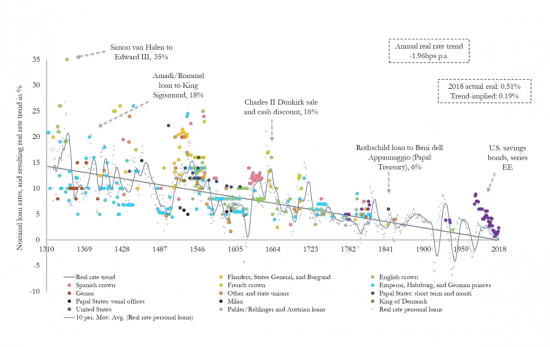

And let's also just look at interest rates.

The data is from the Bank of England. The strong, long term trend in interest rates is downward. It's now around zero. That is one very good reason why inflation is no longer an issue. But the only question is, might that change? That is an issue for another blog, but for now my suggestion is that nothing changes that at this moment. And I stress, that means that there is no reason why the current trend may not be towards negative rates. But discussing that is for another blog.

At this moment the conclusion is clear: any inflation risk now is very small and will reverse. Increasing interest rates is not necessary now. This inflation will, in any event, go away soon and all the increase will do is shift income to those already best off in society - including banks themselves. The government needs to protect its employees and those on benefits from this price change. But that apart, this inflation does not require government reaction. Austerity and interest increases are not in any way required. If they happen then they should in that case be read for what they are, which is the pure politics of upwards redistribution of wealth.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

Agreed.

I think we are being mislead by some the government and their supporters in the media. Richard , I think, disproves their view.

However, housing is a major part of our spending and the price of housing has risen way ahead of wages. But raising interest rates is no solution here either. My kids have mortgages and extra interest would reduce their standard of living and wider demand in the economy as they cut back spending on other things.

My impression is that the economic establishment are locked into the familiar and unwilling, or unable, to employ new thinking. To further depress me, the opposition also seem to be locked into the old script.

We had a twenty year period through the 70s and 80s where inflation was never lower than 5% and peaked at 25%.. that was destructive and prompted the era thereafter where controlling inflation became a priority. We should fear inflation and the damage it causes.

Stop talking in tropes and explain why we have reason to fear inflation now given the data?

Or are you just wasting time here?

Richard, I am not sure you are right on this one. As I recall, the crisis in the 1970s was caused by a large increase in the price of a commodity that we needed to import (oil), without an increase in the value of goods we exported. There was no way that “printing money” could ever solve the problem. Hence inflation.

In 2008, the crisis was caused by banks “printing money” to create mortgages that would never be repaid. When that bubble burst, the money was gone. The banks might as well have never printed it. Austerity was trying to correct for an imaginary excess of money.

Today we have both problems. We have far too much private debt pushing asset prices into bubble territory. At the same time Brexit is wrecking the long-term balance between imports and exports. Gas prices are wrecking the short-term balance. I am not sure how it will end, but I don’t see a simple answer. Only economists and politicians think there is a single remedy for different diseases with superficially similar symptoms.

I am genuinely not sure what you are saying I have got wrong….

>In 2008, the crisis was caused by banks “printing money” to create mortgages that would never be repaid. When that bubble burst, the money was gone. The banks might as well have never printed it. Austerity was trying to correct for an imaginary excess of money.

The usual story is that too much money in the economy drives inflation. Yet the CPI inflation that followed 2008 never exceeded 4%. Also, when Japan’s real estate bubble burst they got deflation.

In theory the quantity of money has absolutely no relationship with inflation. More money means more debt. Add both together and you end up with 0 net worth because money is just a piece of paper or a number in a database that has no value beyond the liabilities that are attached to it.

When people save money that money can no longer be used in the economy, instead, the ones who are waiting to receive the dollar are “borrowing” freshly created money to do business as usual. The money supply grows even though the economy stands still. In a fictional economy where every dollar is saved and the productive output is finite you can have an infinite quantity of money yet no inflation.

There might be people who couldn’t repay their debt but there are also many people who can repay their debt but are bogged down by a huge mortgage that exceeds the value of their home. These people will cut consumer spending and focus on paying down their debt which results in less consumer price inflation.

I’m probably a decade too early but I personally consider 0% interest already austerity. It’s clear that the interest rate must be much lower for it to stimulate the economy and create persistent inflation.

Great blog Richard,

Thank you for this bringing an informed and reasoned explanation.

These price rises in part can be linked to rising oil and gas prices. Putin has stated that $100 per barrel is a realistic future price based on rising demand following Covid.

Brexit of course has had an impact additional costs and complications with our European trade causing scarcity and supply side shocks.

Plus falling retail sales hardly paints a picture of excess demand that Haldane pointed towards.

Spending cuts and rate increases and unwinding QE would not fix any of those external supply side issues. In fact rate rises would accentuate inflation with additional business costs.

And also more net interest payments into the economy may also be inflationary.

You are spot on these inflationary pressures are external and hopefully transitory. Spending cuts and rates rises just serve the interests of the high and mighty.

Thank you for dealing with the troll so brusquely. Of course one can make references to the 1970s in the Daily Mail, since its readers are utterly illiterate economically, but I still find it hard to understand why trolls waste their time here. Presumably, it is because they ARE economically illiterate.

I bought my first house in 1986, and a few pay rises 6% or so as a result of the inflation rates at that period soon made my mortgage quite affordable.

I suggest that a spot of inflation and inflation linked pay rises might be just what many people need right now

While I agree that inflation does not, of itself, appear to be likely to be a long-term issue, I think that the effect of ANY inflation on the poorest in our society needs taking into consideration. The poorest are, largely, those who rely entirely on the state for their income. Those who cannot work because they are too old, or too disabled, or too ill or because the jobs they can do do not exist in their location, plus those whose employers pay them so little that the state subsidises their employment. I don’t know the figures but this amounts to millions of people. They already receive so little that they struggle to meet basic living costs. Their income is fixed for at least a year and, if it is increased it is done on the basis of price increases that have already happened, so they never catch up. Any price increases make their ability to survive even more precarious.

The valid suggestion that ‘ The government needs to protect its employees and those on benefits from this price change’ ignores the reality that it will not happen.

I am old enough to have been at work in 1974/75. I was a civil servant and our pay increased every month with a ‘cost of living’ increase. That is not going to happen now and many will suffer extreme hardship as a result. With the current government and the current opposition I cannot see that changing in the foreseeable future.

I think pay freezes may be over this week…

Pensioners are reasonably protected, even with the end of the triple lock

Public debt to GDP is a useless metric for sustainability of debts because the GDP is not the income of the government. The third chart is exactly what I was looking for.

Interesting report on The Guardian website this morning

https://www.theguardian.com/news/2021/oct/25/millionaires-petition-rishi-sunak-to-introduce-wealth-tax

Blogged

[…] Cross-posted from Tax Research UK […]