The Financial Reporting Council report on the failings of Grant Thornton within their audit of Patisserie Valerie was issued yesterday. The report makes for grisly reading for those who care about the audit profession. A staggering level of incompetence is documented.

Although I rather strongly suspect that many of the so-called audit failures of recent years are inappropriately labelled, because their underlying cause is in the failings of the accounting standards used for the preparation of the accounts of the companies in question, in this case there was blatant fraud going on in Patisserie Valerie which the audit failed to identify over a period of at least three years.

The frauds included falsifying sales income in fashion so blatant that it should have been obvious; falsifying documentation to provide false audit evidence, with the falsification being so amateurish it should have been obvious; failing to check bank reconciliations (perhaps the most basic of all audit tests) properly, and failing to draw obvious conclusions from their obvious falsification; failing to check fixed assets properly (which looked like a pretty minor breach, overall). and failing to check year-end accounting adjustments that falsified the view given by the accounts.

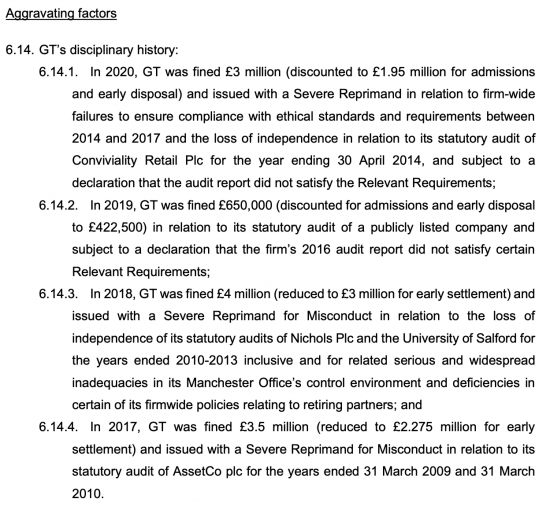

That's a staggering list of failings. Unfortunately, it's not that staggering in the case of Grant Thornton, with regard to whom the Financial Reporting Council report notes these following additional failings in recent years, all resulting in penalties:

I suggest if you wish to wallow in the sordid details of this that reading the FRC report will provide a certain sort of pleasure. I am more interested in why this happened, particularly given that audit failure at Grant Thornton appears to be systemic.

The obvious reaction of an experienced auditor (and I audited for twenty years) is to be staggered that such mistakes might be made. I said so in comments to The Times made yesterday. But the obligation on an auditor is to be sceptical and to not accept evidence at face value. The duty is to ask ‘why?' to determine whether a particular error might in fact be indicative of a systemic failing. I suggest that in this case it is very likely that it is.

What I suspect this case evidences is that Grant Thornton are using staff both too poorly trained and simultaneously inexperienced to undertake the audit work demanded of them. The audit of cash and bank is routinely delegated to very junior members of audit teams as fraud is usually considered very unlikely and so error is rare. Analytical review, which is the process of standing back to look at patterns in audit data that might indicate falsification because abnormalities are rarely very well disguised (and they were blatant at Patisserie Valerie) is frequently poorly done: those undertaking the work simply do not have the experience to do it or the courage to follow through on issues observed. In addition, journal entries are very rarely understood by audit staff who have never had the responsibility for ever preparing a set of accounts (and most Grant Thornton staff will never have done so) which means that they are usually deeply misunderstood.

What I am saying is that I think it quite possible that the audit team on this audit were inappropriately trained for the tasks they were asked to undertake. That was not their fault. It was the fault of Grant Thornton and the audit partner. It only required a less than dutifully diligent audit partner and the chance of a failed audit was easily created.

I say this for good reason. Many will say that this failure shows that there is need for audit firm reform in the UK, but I rather strongly suspect that the reform they will call for will not be what is required. The failing on display is a suspect commonplace, not just in Grant Thornton, but in many of the mass of audit failings noted by the FRC amongst the major audit firms each year.

There is an expectation that we should have cheap audits. Firms deliver them using, very largely, quite junior staff who are in their early twenties, who have almost no experience of accounting, very little on the job training, and who have never done any actual accounting because opportunity to do that is almost unknown in larger audit firms. The primary goal of these staff remains what it has been throughout their lives to date, which is to pass exams and then move on. Audit is for them little more than a ticket to a right of passage, which is qualification as an accountant and the financial rewards that brings. Their interest in audit is marginal, at best.

It is this fundamental structural failing in the supply of audit that is the real cause of audit failure. It will not be resolved without a change in the professional qualification of auditors, without a requirement that they must all know how accounts are actually prepared (because the division between accounting and auditing skills is very dangerous when it comes to delivering effective audits), and most importantly, the price of audit must increase so that people who know what they are doing can be engaged to do it.

This is not the solution being discussed anywhere in the professional right now. As a result audit failure is likely to continue.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

They should have sent the VAT Officers in !

When I joined Customs 40 odd years ago one of the first things we learned was take nothing at face value and be always alert to sales suppression and creation of bogus invoices

Of course….

“[J]ournal entries are very rarely understood by audit staff who have never had the responsibility for ever preparing a set of accounts …. which means that they are usually deeply misunderstood.”

In which case, is there not, perhaps a need for something additional in the education/training; perhaps between the B.Acc and the CA/ACA, where the ‘junior’ would first be required to serve a quasi-apprenticeship within a company for (say) six months before undertaking audit work; working on the preparation of accounts (similar to the year abroad in a language degree), in order better to understand the relationship between ‘theory’ and ‘reality’; perhaps sponsored by the hiring accountancy firm? Perhaps it already happens, although I can readily see some easily thrown up objections or practical problems – but within the audit community, addressing them directly may “concentrate the mind wonderfully”, as Dr Johnson said about a man facing his imminent hanging.

I think that an excellent idea

But I had done a year’s work in an accounting firm before start9ing my ACA training, so of course I agree

I am not sure how I would have audited otherwise, but plenty did and still do

I trained with a small accounting practice back in the days of cash ( 70’s ) so all sole traders and small companies. I’d do the accounts , the audit stuff ( as it was back then ) but always get the bank recs right. First journal entry the partners put through would be credit sales , debit drawings !! probably not that funny but that’s how it was back then and I have to say I enjoyed the work.

🙂

Ah yes but it taught to challenge everything , believe nothing , verify everything concept but in a very unsophisticated ( but real ) environment. In the very basics it was often a bag of bank statements , cheque stubs and invoices. Often smelling of your client ( farmer , fish merchant etc ) and you just knew they were lying to you . I loved them as some were real characters . I had one who could not read or write but worked his @@@@ off to become very wealthy , kept offering me bribes to cook his books even more than he did ( I knew , could not prove it ) , always said no. I’m sure most CA ‘s who qualified in small firms back in the 70’s have similar stories. Or maybe it was different in Aberdeen and everyone else is honest. Maybe Richard a thread on it would be good. After all not all CA’s are big firm and I’ll bet we all have great stories to share. Just a thought . Hope I’ve not annoyed you as I know you don’t being annoyed by oiks

I lived my client who was a gifted musician and deeply autistic with words

So he wrote up his books in coloured pencils to represent the expenditure analysis

It worked just fine….we all knew the code

HMRC would reject it as non digital now of course

I love that story and it’s so true to small practice and a damnation of the app culture we now all have to endure. I also had a cheque trader as a client ( I think they were called tick men in England ). The principal was a dead ringer for Captain Mainwaring in Dads Army and also just as pompous. His son who looked nothing like him and massive was the collector. I have many more but I won’t bore your contributors ( I also worked on an abattoir audit and have a really funny stories about that ).

You learn a lot in small practice and most of it nothing to to do with SSAP’s or accounting for that matter.

SSAPs? That takes me back

Unfortunately, my former colleagues, I’m a retired VAT officer as well, very rarely get to visit business premises any longer. The move to regional offices has a lot to answer for.

Examining transactions and the document trail that evidence them is best done where they take place.

As I like to explain: talk to the FD or the auditors and they will explain how the accounting system works; talk to the accounts manager and they will explain all the amendments to the system they have made; talk to the accounts clerks and they will tell you all the things that still don’t work and the work arounds they have to do to make it work. You can’t do that from an office 200 miles away.

🙂

So true

It’s called auditing by walking around

A variation on economics by walking around

Both work

Auditing it seems is just a way for dodgy geezers to get a someone to hold up a mirror so that they can see their reflected glory and pass themselves off as above board to the market.

It’s amazing that you’ve got something like public choice theory pointing out the agency problems in the public sector and yet on this they don’t seem to have anything to say about auditors being given huge sums to effectively turn a blind eye.

I agree with you that I can’t see it changing unless investors themselves (who come first as I understand in the scheme of things) kick off and do something about it.

I think that you mean “grisly”

…but as a pedant, I do admire your liberation from the compulsion to correct typos and literals!

🙂

I write many thousands of words on here, plus others where I am under pressure to get the typing right

I could go for perfection here

I could have everything proof read first

But there would be less content and it would be much delayed

So I accept the compromise of having some errors that I do not spot when I read through – because like everyone I tend to read what I think I wrote

I agree that many auditors do not know how accounts are prepared. Even more important, in my view, is that many auditors have never produced a set of accounts in a business setting; there is a huge difference between theory and practice.

There is even more confusion when audit teams descend on entities working to Charity SORPs where numerous restricted and unrestricted funds replace the single P & L account that they are used to.

The teams arrive with checklists and the instruction to work methodically through them; the audit partner only appearing for the wash up. There is a great deal of learning on the job when the check list and practice disagree.

But two unreported overdrafts imply hidden cash books and a failure to seek account substantiation from the bank lending entity.

Reading the full 65 pages it’s pretty clear fake documents were being created to justify the journal entries (fake documents that were so bad they were clearly fake). Amazed nobody has been charged with fraud

Still shocking audit work though. Fine seems v low in comparison to the offences.

Agreed

Best 65 pages I have read for a while

The Fraud Act (2006) was enacted to replace an existing fraud act that practising lawyers and barristers knew had proved completely useless. It was debated in Parliament just as the Financial Crash was about to break a mere mile away, and Parliament carefully omitted to give the Act any effective leverage in the financial sector. The proof of that was discovered soon enough by the Financial Crash, quickly demonstrating that the Fraud Act (2006) was indeed as useless as its predecessor in the capacity of prosecutors to apply it effectively to the financial sector.