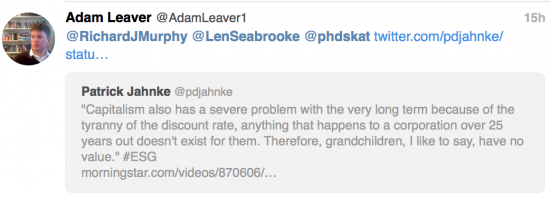

Adam Leaver of Sheffield University tweeted this comment last night to Len Seabrooke, Rasmus Christensen and myself. We are all working on research proposals at present:

Patrick Jahnke is right: this is a fundamental flaw at the heart of modern accounting. I have said this morning that nothing lasts forever, and I stand by that. It's wise to realise that's true. But to assume nothing has value in a generation's time is as flawed as thinking anything lasts in perpetuity. And what the practice of discounting in accountancy means is that no company plans for a generation hence. And yet it is believed that investing in the shares of these companies is a rational basis for making pensions provision.

That this is not true - because these companies have no plan for the time when pensioners will want to realise their investments - should be apparent. But it is not.

The fact is, we're really not very good when it comes to matters of time.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

Agreed

The pension funds themselves have previous on this. Their narrowly driven focus on retaining the value of the fund comes at the cost of the generations who are working now to the point that eventually their wages will be absorbed into the fund and they have no work and the work is sent abroad or to a computer.

Then what?

This is what the so-called ‘millennials’ are up against. And I’m with them. But not if they think that Trump, Farage and Rees-Mogg are the answer.

That isn’t what discounting means. By your logic because discounting means that nobody in their right minds should invest in fixed capital. You and Adam Leaver have also made a very basic error, though it’s clear neither of you know what that is.

But I’ll humor you.

How would you value a long term investment, without discounting?

What would an investment of an arbitrary £100m be worth for a company in 10 years time? Or how much would the same investment in a 10 year government bond be worth?

How would you value any future cash flow without discounting?

We both know exactly what it is

And what we are both asking is why on earth any company should value its performance on the basis of changed assumptions as to cash flow that are inherently unknowable at discount rates that are inherently unknown, all of which however suggest that the time line for meaningful action is very short?

It’s the absolute antithesis of value creation and so far from what accounting should do that accounting is profoundly misleading as a result

If judgement is to be the basis of accounting – and it is – this pseudo science is possibly the worst expression of judgement available

Judging by your answer, I’m not sure you do know what it is.

“why on earth any company should value its performance on the basis of changed assumptions as to cash flow that are inherently unknowable at discount rates that are inherently unknown, all of which however suggest that the time line for meaningful action is very short?”

Companies aren’t valuing their performance based on discounting. They are valuing future cash flows or the value of assets. Likewise, they also value their liabilities using a discount method.

Discount rates are not unknown. They are very well defined at any given time. Accounting is not a study of the future – it is a study of the current. You are suggesting that accounting is somehow getting things wrong by not being able to predict the future.

I the can also safely assume that you think depreciation is also wrong, given it is a basic form of discounting?

“If judgement is to be the basis of accounting”

So your basic point is that discounting is somehow incorrect.

I ask you again. How would you value any future cash flow. Judgement?

You haven’t managed to answer what you would do if you aren’t going to use a discount method.

You clearly do not realise that accounting measures income as the change in value between two balance sheets and that now is as much dependent on changes in discounting assumptions as anything that actually happens

And discount rates are not fixed

Nor are the methods of estimating cash flows

So I am happy to put you right

I also happen to think discounting – which is possibly the most openly manipulatable tool for investment appraisal that there is – is absurd. It ignores anything but cash flow for a start – and is open to total abuse on shared costs

So to claim it is in any way rational is beyond stupid: it’s just wrong and the tool of recourse of the charlatan who wants to justify whatever they have already decided to do and whatever total income they want to disclose

And how would I value a cash flow? I probably would not: it’s a waste of time. All investment decisions are made by gut. If you don’t know that you’ve probably never made one.

“You clearly do not realise that accounting measures income as the change in value between two balance sheets and that now is as much dependent on changes in discounting assumptions as anything that actually happens”

Accounting is a static measure of a balance sheet. Assets versus liabilities. Not two balance sheets, because that is nonsensical. It is dependent on discounting, but discounting is not based on assumptions. By definition discounting uses an observable discount curve – usually that of the government debt curve.

What you are trying to say is that the discount curve changes. Well of course it does. Nobody can accurately predict the future. But as I have said before, accounting is not trying to. It is a static process, accurate to a given historical date. Not a predictive future date.

“And discount rates are not fixed”

See above. Does not make discounting any less relevent.

“Nor are the methods of estimating cash flows”

Fixed cash flows are not estimated. By definition.

“So I am happy to put you right”

I am assuming you are joking.

“I also happen to think discounting — which is possibly the most openly manipulatable tool for investment appraisal that there is — is absurd. It ignores anything but cash flow for a start — and is open to total abuse on shared costs”

The reason people use discounting is that it is NOT open to manipulation. The discount curves are observable. So a company could not fudge their discounting. Shared costs is just wiffle on your part. Future cashflows are still discounted regardless of their function or relation, simply to get them into present value terms for accounting purposes.

“So to claim it is in any way rational is beyond stupid: it’s just wrong and the tool of recourse of the charlatan who wants to justify whatever they have already decided to do and whatever total income they want to disclose”

OK. So as I ask again: How would you value a future cashflow? Systematically and without recourse to guesswork.

“And how would I value a cash flow? I probably would not: it’s a waste of time. All investment decisions are made by gut. If you don’t know that you’ve probably never made one.”

And here you show that you clearly are joking. Few investment decisions are made by gut alone. And i’m sure accountants and auditors would have a field day if you simply said that you simply won’t value a future cash flow. Because it’s a waste of time.

You are joking right? Because if you aren’t….well…..you must be an idiot.

I think all this really shows us is that you simply haven’t got a clue what you are talking about. Discounting is simply a way of talking about future values in present value terms. It’s the reverse process of taking a fixed sum of money today and investing it at a fixed rate in a safe, government security. By that very same reasoning, you can discount at the “risk free” rate (something you also clearly don’t understand, given you other comments) because it is a proxy for the return you could have earned by investing in the otherwise safest security available. It is literally nothing to do with the risk of the company, and totally extrinsic to anything other than what a sum of X is worth today, when invested for a given length of time.

Which is why accountants and auditors use discounting.

Rather than guesswork, which is what you are suggesting they use instead.

Which given you are trying to set up a “corporate accountability network” makes even less sense. I’m sure it will be totally OK when people start making judgement calls based on their gut and passing them off as accounts. It will definitely help. Really. It will.

Oh, and I’m guessing I’ve made a fair few more investment decisions that you have. And when I do I certainly don’t just “use my gut”. And frankly, anyone who had ever run an investment or business would never say anything quite as retarded.

Damien

First you are wrong. You say ‘Accounting is a static measure of a balance sheet. Assets versus liabilities. Not two balance sheets, because that is nonsensical.’ This is incorrect. It shows you do not understand IFRS accounting, at all. I think you need to do some reading because you clearly do not know how accounting now measures income.

Second, you reveal yourself as an investor. That’s fine, except your methods are utterly irrational. Read Mark Carney today. He knows, as I do, that discounting lets us ignore climate change. The discount rate puts it beyond the event horizon of significance, and so who cares? Well, actually, we all should.

Let me explain why: the collateral for most of the world’s debts will disappear in the event of global warming. But that is still too far away for you to worry about if you discount the future. So you take no action. And then the whole system fails.

The gut says act. Your model says all is fine. Your model is wrong. The gut is subjective, and right.

Accounting survived without discounting until 2005, to its advantage. It very definitely needs to do so again. You can play spreadsheets if you like. But in the real world where real decisions are made they are the enemy of good decision making. As is discounting. Judgement is what matters, and the lower of cost and net realisable value always and more than adequately allowed for that. And we would not have had 2008 if that rule had still applied.

I note your name calling. Call me what you will. Judgement wins. And to pretend any model is anything but a mechanism to justify judgement is to simply con yourself.

Richard

I’m starting to understand. That you don’t understand discounting or accounting.

The very definition of a balance sheet is that it is a snapshot of assets versus liabilities at a given point in time. Maybe you should look it up.

There are different ways of preparing a balance sheet – IFRS13/GAAP etc, but there is only one balance sheet, and that balance sheet is only accurate for the day it was issued.

I also get the impression that you are confusing aspects of the balance sheet, income statement and cash flow statements for company accounting. Basic accountancy. Again, go look it up.

“that discounting lets us ignore climate change. ”

No it doesn’t. It means nothing of the sort. All discounting does it allow us to take the future value of a cash flow and turn it into a present value.

“Let me explain why: the collateral for most of the world’s debts will disappear in the event of global warming”

And here is where you show your lack of understanding. Sure, the collateral will “disappear” under discounting. But discounting works on both sides of the balance sheet equally. All the future assets will disappear, as well as all the future liabilities. You’ll also notice that balance sheets always sum to zero, rather making the point.

By your crazy logic, companies shouldn’t ever invest in fixed capital, as their investment will discount to zero over time. Of course, in the real world they do – because the discounted cash flows tell you nothing about returns. It is ONLY a static measure of what a future cashflow is worth in present value terms.

It does not try and predict the future, which is what you are claiming it does. It tells us what future cash flows are worth TODAY based on investments you can make TODAY.

For example, discounting allows you to see which you would rather have today. £100 in your hand or a different sum of money invested for a future return. Tomorrow, when markets and prices have moved, those may not be the same.

Discounting has been around as long as interest rates have, given they are the opposite sides of the same coin. Irving Fisher formalized it in his 1930 book “The Theory of Interest” but discount techniques have been used for a very long time before that – the Babylonians discounted interest rates in their mathematics, for example. Discounting didn’t just appear in 2005.

“Judgement is what matters, and the lower of cost and net realisable value always and more than adequately allowed for that. And we would not have had 2008 if that rule had still applied.”

Judgement does matter. But again you are showing you lack of understanding. Discounting is a way of measuring what something is worth today. It is NOT trying to predict what something will be worth tomorrow. Discounting is not a predictive analytical tool.

2008 would have happened, because discounting literally had nothing to do with it – and judgement did. People judged that AAA CDO’s couldn’t go bust. They did. How did that work out? Discounting what are now significantly lower future cash flows off the treasury yield curve had nothing to do with the financial crisis, other than measuring the fallout.

Given we cannot predict the future, all investment decisions involve some judgement – fine. But saying judgement is a good way of valuing things is pure nonsense. Whose judgement would you use? How would you formalize it? Are you saying that a company could present it’s accounts based on a series of judgements? It’s unadulterated nonsense – from someone claiming they want MORE corporate accountability.

“I note your name calling”

Pot calling kettle black – you started the personal attacks with “If you don’t know that you’ve probably never made one.”

OK, a professor in political economy and an FCA, but I don’t understand….that’s your claim. It lacks credibility from the outset, I’d suggest

But it’s also wrong

For the record I never said there was more than one balance sheet (although, depending on the accounting convention there are in fact, lots of balance sheets)

What you are getting wrong is your failure to understand that income in IFRS is the movement in value between two balance sheets (subject to dividends paid and other equity changes, of course). If you don’t get that you do not get IFRS, at its core.

And what I am saying is valuing that balance sheet at discounted value is wrong, because it does not reflect true value; fails to take objectives other than profit into account (and yes, they exist: see Mark Carney today, again); and is too subjective as a basis for valuation because in most cases cash flow is not known and where it is (e.g. liabilities) changes in rate produce decidedly perverse outcomes.

Historical cost is less subjective now.

So too is cost or net realisable value: capping all upsides in a low inflation environment.

And that’s what you’re ignoring.

Now, very politely, stop wasting my time

“OK, a professor in political economy and an FCA, but I don’t understand”

It’s pretty clear you don’t.

“For the record I never said there was more than one balance sheet”

“You clearly do not realise that accounting measures income as the change in value between two balance sheets ”

your words, not mine.

“What you are getting wrong is your failure to understand that income in IFRS is the movement in value between two balance sheets”

No. This isn’t the case. A balance sheet is simply a statement of assets and liabilities of a company. It has nothing to do with income or revenue.

As the name implies, the INCOME STATEMENT deals with a company income and revenue. This is very much the case in IFRS.

“And what I am saying is valuing that balance sheet at discounted value is wrong, because it does not reflect true value”

OK. So how would you judge fair value for an asset or future cash flow, without discounting? How would you do that and make it consistent?

“fails to take objectives other than profit into account”

Balance sheets don’t have anything to do with profit. Again, they are just assets and liabilities, and you are confusing the balance sheet with the income statement.

“too subjective as a basis for valuation”

As opposed to subjective, judgement based guessing I suppose?

“because in most cases cash flow is not known”

Cash flows will for the most part be known in a balance sheet. Even future ones – because the cash flows that go into a balance sheet will typically be contractual. Again you are mixing up the income statement. The unknown, typically revenue based cash flows go into that and the cash flow statement.

“Historical cost is less subjective now”

The wonders never cease. We know the past exactly. The future, not so much.

I really think you should go and take a refresher course on accounting and basic finance – this is basic stuff you are getting wrong here.

With respect, it is clear I do know accounting and you do not

You obviously have not the slightest idea what IFES accounting does

I am not wasting my time anymore

I suggest you do the reading. And I’d also suggest you do not waste my time again

“With respect, it is clear I do know accounting and you do not”

Really? When you don’t seem to understand balance sheets, income statements and basic discounting? The best you can do is to say I don’t understand it – when I have pointed out the rather large errors you have made?

And from another post on this thread:

“Let’s do a simple comparison and say that what happened before IFRS was conasiderably more useful.”

That would be IAS, used from 1973 to 2001.

Which formed the basis of IFRS – and used discounting.

No it was not IAS

It was UK GAAP that I was referring to

Your ignorance on view, again

IAS was almost universally ignored, for good reason pre 2005

“No it was not IAS

It was UK GAAP that I was referring to”

UK GAAP….otherwise known as IAS plus? That UK GAAP? The one which is based on….IAS?

Either way, these basic accounting rules are the same in IAS, UK and US GAAP and IFRS.

“IAS was almost universally ignored, for good reason pre 2005”

Well, they were replaced by IFRS in 2001….and they weren’t ignored at all before then. They were the most common accounting standard across the EU. But hey.

Oh, and I just noticed this…..

“For the record I never said there was more than one balance sheet”

In your reply to Elliot…..off you go again about there being more than one balance sheet….

” tell me how it isn true and fair to have an asset on two balance sheets at once”

Your knowledge of accounting history is clearly as poor as your accounting. IFRS adoption was in 2005.

And if you don’t understand that two balance sheets are always impacted by one third party transaction then you are in as deep trouble as Elliott is when it comes to having a clue as to what accounting is about.

You really are making this stuff up.

But what you both convincingly prove is that your accounting perceptions are so far removed from reality that you have no clue about what that reality might be

Which has been my pint all along

This debate is closed

Now stop wasting my time

Richard a very interesting dialogue with Damian. For all the accounting speak discounting has to exist using the yield curve and credit spreads. I really cannot see how that can be in dispute. The skill in analysing a set of accounts is to use judgement on the numbers because the numbers tell you only a snapshot at a given time using assumptions (like a discount rate).

It is healthier to see that kind of dialogue as opposed to just a blind acceptance of approval from many readers on here who haven’t the foggiest idea of whatveitger if you were talking about.

Justify your claim

From first principles

And consider the possibility that accounting is not an economic discipline at all whilst doing so, but is a form of social communication

And then consider your comment in that light

Well there you go i now see the basis of your argument. I see accounting as a picture of a company reflecting a basis to ascertain its value and potential under assumptions known at the outset. So I look at them as the starting point as a basis to invest.. you clearly don’t like that in some way which is fine and want to widen or change the remit of public accounts, that is fine also. You have an agenda which is fine also. It is also right, from my standpoint to use an intelligently derived discount curve as long as the assumptions are clearly stated. It allows for the basis of analysing a business. Just because you have a different agenda ( which I am not criticising btw) doesn’t make this wrong.

It does make it wrong if it does not suit the public purpose

What is the public purpose of discounting in audited accounts?

“Public purpose”??? As I say it helps existing and potential investors including pension funds. Is that in the public purpose?

How does it help them?

Ask any investment analyst on either the buy or he sell side if they use a discounting at some point when valuing a company and they will all say they do. So for investors,

And do they know why?

I don’t know much about requirements for accounts, but from first principles, discounting should be done with reference to the yield on index linked gilts (as the appropriate real risk free rate). The 25 year rate is currently negative (so the value of £100 in 25 years’ time is currently greater than £100) – so what’s the problem?

The discounting is not done at that rate: companies do not have risk free cash flows

The “with reference to” was to brush the risk adjustments required under the carpet. But it’s still the case that if a company has a real (inflation adjusted) liability in 25 years time that is £100 with 50% probability, and £200 with 50% probability, and risk free real rate is -1%p.a. then investors in this company *should* recognise that there is a future cost with present value of the order of ((1+(-0.01))^25)*(0.5*(100+200)) = £193 i.e. greater than the certainty equivalent payoff of £150 because of the time value under negative rates.

Obviously if accounting regulations don’t demand that they recognise something along these lines then that’s an issue, but the issue is one of accounting regulations, not the theory and methodology of discounting and financial economics generally.

I don’t really see the issue with discounting under the present negative interest rate environment, which reflects market expectations of low or negative future economic growth. The problem with discounting is when there is a disagreement between some sort of scientific expectation of the future (e.g. climate change causing negative growth) and market expectations (yah, the future will be great). This was the case around the time of the 2006 Stern Review. Discounting was a big issue.

See comment made elsewhere

@dcomerf

I know I’m being pedantic here, but the equation you gave does not equal £193. By my reckoning, it’s a shade over £116. If you’re going to stick equations in, make sure you get your +/- signs the correct way around (by the way, using 1.01^25 gives close to the number you quote).

I actually think the correct equation is: cost today = ((100+200)/2)/(0.99^25). The numbers from both equations are very close, 40 – 50p in it, but I feel this precision should be important when discussing accounting practices. Otherwise finance’s claims to being a science wear ever thinner.

I also appreciate that people like to round things, so maybe the difference is considered trivial, but surely workings should at least begin with the proper form of the equation? Maybe not?

Thanks

But there is no science here

Processing what is, in the main, made up data does not produce accuracy just because a formula is correctly applied

I accept some liabilities can be contractually forecast as to cash flow

But earnings? Never. So GIGO applies

The discounting is not done at that rate: companies do not have risk free cash flows…a rational discount rate reflects both the yield curve and credit spread over the risk free rate (by comparable companies market bond prices). So the discount rate is never flat and the rate will change each year,. This is a trivial method of calculation. Of course it does not reflect what will happen in the future it reflects the best way to analyse cash flows given all the information we have at our disposal at present.

I am not achartered accountant, so i am not aware of common practise but work in the pricing and trading of infrastructure assets. I actually know Patrick Jahnke – a decent though unspectacular fund manager. Certainly no mathematical god who will shake up the world. Of course some people who come across a PHD view all they say as gospel!!

I know what discounting is

I know how accounting uses it

I am saying it should not use it

It may be an investment appraisal tool – and a poor one at that – but nothing justifies its use as a measure of accounting value, and its use as such results in anything but a true and fair view – as we have seen

Yes, definitely, I agree that input data has to be meaningful. To continue with the scientific parlance, what’s the error on the discounting? Without access to time travel, absolutely massive…

I’d still argue that, regardless of the validity of the data input, conclusions based on a model which does not make “physical sense” can be quickly discounted. I’ll admit that I get triggered by arguments which are dressed up to look clever but don’t stand up to basic scrutiny, which is probably why I ended up dissecting the claimed values and methods in so much detail.

I’m certain we’re both singing from the same hymn sheet :).

There is a very evident distinction (and difference in behaviour) between a family business and a corporation with essentially random shareholders. You might not agree with the concentration of wealth but consider something like the Duke of Bedford’s estate in London. This covers most of the area between St Pancras / Euston and the British Museum, so Bloomsbury, Russel Square (actual name of the Duke), Tavistock Square (honorary title of the eldest son), etc. This has been preserved, maintained and managed for over 250 years. When you are managing properties on 99 year leases you are not taking any notice of a 25 year discount rate limit or the fact that you will be long dead by the time the renewal comes round. Companies run by the founder also show radically different behaviour – Amazon is a classic example. Huge losses for the first 15 years and no sign of any dividend, but Bezos cares about neither of those as I think he is aiming for World domination of all retailing. I am a bit of fan of Banco Santander where Anna Botin is I think the fourth generation of the family to be in charge. That is why I don’t have too much issue with outsize rewards for e.g. Bill Gates. Those sort of folk created something and have ‘skin in the game’, i.e. a huge ownership interest. Where I do have a huge issue is telephone directory salaries for the directors of most large companies. For the most part they have no stake in the business beyond their salary / options, and have simply been good at either climbing the greasy pole or known the right people. For the most part they are in it for what they can get, don’t have any better skills than many other possible candidates and are happy to take actions that are good for them personally in the short term even if bad for the company, shareholders, employees, etc in the long term.

[…] have little doubt that some who yesterday called me an idiot and worse in the comments section of this blog for questioning the investment appraisal technique known as ‘discounting’ will apply similar […]

I’m not sure exactly about discount rates and I’ve gone online to look at the definition.

All I see is something that can be abused – despite the definitions doing their best to sound scientific and legitimate.

Maybe a lot of this type of accounting is aimed at assessing risk and reward for the financial sector but also seems to have taken on a life all of its own?

The question is this: When will accounting just go back to simple math? You’ve either got a certain amount of money at the time or you haven’t. And it is being moved around into this and that.

The profession needs to learn how to call a spade a bloody spade in my view.

Everything else (for example ‘discounting’) is just pure speculation and guess work.

BTW – I fully admit that I have a jaundiced view of the whole profession and practice

– so, sorry about that. They’re at the same level as orthodox economists in my view.

We all know what the problem is: it’s how discounting and other accounting methods are used to create a false impression of ‘all is well – for ever’.

Well said on spades and spot on

I have to admit that I couldn’t follow that argument between Richard and Damien. And I’m not sure I need to, Richard’s point seems fairly straightforward.

Am I alone in sometimes thinking that a lot of what comes under “accounting” (and the same very much applies to “economics”) has left behind straightforward, practical considerations and become a religion, the mysteries of which can only be understood by the self-appointed priesthood?

You are exactly right in your perception

How else to ring fence the fees?

An intelligently derived discount rate does give a true and fair view given the information at this time. Tomorrow the discount rate calculation will change because the yield curve and credit spreads will change. Again don’t pretend it to be a mechanism to look into the future…btw what do you propose instead?

Instead? Let’s do a simple comparison and say that what happened before IFRS was conasiderably more useful.

Don’t go back to abacus look forward and use the most precise way to discount.. I agree the one you portrayed at the outset is poor and not one that is used in the trading of assets in the real world

No method of discounting provides an objective basis for accounting, auditing or reporting unless cash flows are guaranteed

So it has almost no role in asset accounting

And the consequence of its use for liabilities is so bizarre in many cases that the resulting reporting is rendered absurd

I’m sorry – but this is not a reliable basis for reporting and that is what we need

Richard,

How would you, in accounting terms, deal with this problem:

A company enters into a contract to buy machinery. The machines are large, and will take two years to build before delivery. The price of those machines is agreed in the contract, but the payment is only due on delivery (for simplicity).

What would that look like on the balance sheet?

Likewise, the same company uses a lot of fuel, and because of this buys its fuel forward in the market to hedge. As such, it has entered into forward contracts which settle on future dates, where the future cash price of the fuel is known today for delivery on that future date.

How would you account for that?

The first is a capital commitment: it is not on the balance sheet until delivered

If the contract does not involve a change of title immediately (and it probably won’t) then the payments due are accounted for as cost is incurred. That may well be as a prepayment until delivery is made. What else would you expect?

The second is a standard hedging issue: what are you asking? The accounting depends on the contract and may and may not require accounting now depending on that contract.

I think you’re trying to play simply games, rather badly, and that’s boring

No, I’m sorry but you are incorrect here on both counts.

For the machinery:

Under IAS37/IFRS16 or UK GAAP this is a provision, and needs to be accounted for. The contract sits on the balance sheet. You own the asset even though it is not paid for or delivered yet. That is what a contract obligation means.

The delivery value of that asset will be discounted, but the asset (or contract for the asset) cannot be left out of the accounts or balance sheet.

For the hedging contracts:

Futures contracts are assets and are duly represented on the balance sheet. Forward contracts (I am assuming you know the difference) are treated slightly differently (as they are deliverables) but still need to be represented on the balance sheet (under IFRS7/IFRS9/GAAP). There is no question of this, and definitely no “may or may not” requirement.

I asked these questions as I am concerned that whilst you claim to be an accountant, you don’t seem to possess the knowledge of one.

And I said it depnds on the contract

You chose options after the event: I gave deliberately open ended answers not knowing enough to do more

So you are playing silly games

As I expected

In other words, you’re a troll.

But I have a question for you too: tell me how it isn true and fair to have an asset on two balance sheets at once. And why is that the case? And does it make sense?

The question is not what arethe rule: they’re crass. The question is why the rule exists. Justify double counting, please.

Two balance sheets? At once? I’m really not sure what you are talking about. Could you explain which two balance sheets you are talking about?

A company only has one balance sheet. That might look slightly different under different accounting standards, but there is only one balance sheet.

It really doesn’t depend on the contract though. The contract is tied to the acquisition of an asset, which means it is required, by law, to be accounted for on the balance sheet.

If that asset hasn’t materialized (i.e. is a future asset, on order etc) then the only change is the value of the asset is discounted to present value terms. By the same token, the cost of that asset (i.e. the liability) will also appear on the balance sheet, also in present value terms.

For example:

An airline enters into a contract to buy some aircraft. The delivery time is 2 years. Cost is $100m.

For simplicity, the contract is not re-negotiable and the full amount is paid on delivery of the aircraft.

The aircraft will appear on the balance sheet’s asset side, at a value of $100m less discounting – so roughly $95m in today’s terms.

The cost of those aircraft will appear on the liabilities side, at $100m less again the discounting, so roughly $95m.

Assets and liabilities match exactly at the conception of the deal, when the contract is signed.

Over time this may change as the value of the aircraft changes (in this case let’s assume that the contract is a fixed price contract, not variable) but at inception the two sides will be exactly equal, by definition.

In short, any asset or liability MUST by LAW be included in the balance sheet statement. You don’t have a choice and there are no exceptions – which is what you are suggesting (“it depends on the contract”).

The two balance sheets are that of the acquirer and seller – and this accounting puts it on the balance sheets of both. You can’t even understand the question so narrow us your perception. That is double counting. And you can’t even see it.

And I note your simplified contract, and the fact that my comment was subject to contract. You did not answer my question, whilst post event justifying your own claim

No wonder accounting looks like fabrication……

And your claim that this is the law is not true: this is what you interpret accounting standards as saying in the case you made up. I am aware of the relationship of those standards with the law, but to claim this is the law is wrong. On different assumptions, different standards ( we have had them) and different contractual conditions ( yours is supremely artificial) differing consequences would flow and be entirely legal.

And also meaningful: accounts that show assets that do not exist, and might never exist, are difficult to justify as true and fair

And as I argued from the outset, when numbers might be this removed from reality ( and this accounting is far removed from substance ) then no wonder accountancy and auditing is in a mess and ripe for reform

But most of all, I reiterate, you are trolling and that is too boring to be bothered with: please don’t call again

I’m honestly scratching my head here. What you have said is nonsensical.

This transaction will indeed appear on both companies balance sheets. Why is that surprising? The buyer will have an asset (aircraft) and a liability (cash). The manufacturer will have an asset (cash) and a liability (aircraft).

It is most certainly not double counting. It’s BASIC accounting.

I think though you are trying to say that balance sheets are reconciled between companies……or something???

I only simplified the contract in this example for the sake of clarity. ANY contract of any net or possible value needs to be included in the balance sheet. This is NOT optional, and is a legal requirement, as of today’s laws and accounting regulations. Don’t try and squirm out of it by saying some other standards don’t require this because in my experience of the main accounting standards used in the UK, US and EU, ALL very much do.

Supposedly you are an accountant, so should know why this is done. Specifically to stop companies holding assets or liabilities off balance sheet and potentially hiding the details of their business. It can be punishable as a criminal offense (fraud or misrepresentation).

“And also meaningful: accounts that show assets that do not exist, and might never exist, are difficult to justify as true and fair”

The contract exists, and is a proxy for the asset. That is enough in accounting terms. What would you rather have? A system where people can choose what they feel like putting in their accounts? Wouldn’t you want to know, as an auditor, regulator or investor if a company has signed a contract to buy something?

In your world though, it seems it is better to not worry about any assets or liabilities until they happen.

Which makes even less sense when you think about it. By your logic the buyer of those aircraft would owe the $100m, and would have to account for that, but wouldn’t be able to account for the asset they’ve purchased till they pay for it.

Mindblowing.

Elliott

Let me explain this, very simply, because you very clearly have a problem with reality.

Let me play your game. A company wants to buy a plane for £100 million. It signs a contract, you say. It is irrevocable. There are no conditions on non-delivery attached. Let’s assume such a contract exists (although it very obviously does not).

And let’s assume that the plane maker can’t believe its luck and signs. The only condition is it is not paid until the plane is delivered. It’s a simplifying assumption. That’s all, rather like yours.

The plane will take 2.5 years to deliver. There are a couple of balance sheets in between.

Your suggestion is that on day 1 the purchaser accounts for the plane. They debit fixed assets. They credit a liability account. And on delivery they credit cash and cancel the liability. That’s your suggestion.

Let me also note the manufacturer’s accounting. For 2.5 years they build a plane. It is on their balance sheet. It is work in progress. They debit that account and they credit income. Not to the full value of course: that would be imprudent. But this asset – work in progress backed as having worth in part by physical existence (there is no work in progress without it, let’s be clear) and realisable because of the contract – but still worthless without the tangible existence of a part built plane -is firmly on their balance sheet until delivery day. And rightly so. It has to be.

So we now have a part built plane on each intermediate balance sheet date.

And two balance sheets.

A built plane that does not exist is on one balance sheet, you suggest. As is a liability that is not yet due, precisely because there is no plane to pay for.

And a part built plane is on another balance sheet.

And you say having more than one plane (just before delivery it could be two planes, in effect) on two balance sheets is true and fair accounting when there is but one, incomplete, plane throughout this period.

I say it isn’t. The substance is that there aren’t two planes. There is one. And it belongs to the manufacturer. The buyer does not have a plane. They have a commitment to pay for a plane. And in the scenario I have described nothing more until the condition for liability – a complete plane – exists. Then they have to pay. Then they have a liability. And a plane that is theirs.

Now of course I know economic substance requires on occasion that we ignore the form of a contract. I agree with that. But here you are letting legal form create an asset that does not exist – a plane. And you are describing it as a fixed asset when it is not. It is not owned, and there is no liability to lay for it: the conditions attached to liability (the plane being complete) have not occurred. So to claim there is a liability is also wrong. It does not matter that you discount it: the reality is it does not exist.

But you want to say that your suggestion is true and fair?

And you want the plane, as I suggested was the case, to be in two balance sheets at once, when there is only one incomplete plane?

And you think it mind blowing that I say that this is inappropriate accounting?

The problem, I assure you is all yours. This is accounting as fraudulent misrepresentation of the truth.

No wonder people do not trust accounts.

No wonder there is an audit problem.

And what gets me is that you think it professionally reasonable to think you might ask someone to sign accounts that include this fraudulent misrepresentation of reality? I’d call that professional misconduct. And I’d suggest the true and fair over-ride would let you ignore the diktat of any standard that might require the accounting you suggest appropriate, because it is wrong.

The only thing mind blowing is that any accountant could think this proper accounting. It isn’t. And it never could be.

And that is why accounting needs reform.

Richard

Sorry Richard but you have it literally all wrong.

I chose this specific example because it is similar to a deal I last involved in very recently.

The real deal involved several aircraft, but the contract stipulated a minimum number to be bought, paid for and delivered barring acts of God. All these aircraft, despite none yet being delivered (and some may never be) must be accounted for. Provisions legally have to be made.

The bulk of the payment is due at delivery. I just said all in my example to simplify it.

You are quite simply wrong that there are “two” aircraft in the example. It is basic accounting. On one company balance sheet it is an asset and the other a liability. One aircraft.

The contract is a proxy for the asset in question, till delivery. All your nonsense about part built planes is just that. Nonsense. Even if the manufacturer didn’t build a new plane they are still obligated to deliver one (this happens regularly via aircraft leasing).

What you are suggesting is that a company can simply ignore any future contractual agreements in accounting terms until delivery.

This violates the current and historic rules of accounting as well as the law, in this case. By doing what you suggest a company could easily cook its books. Hence the law.

I really struggle to see how, claiming o be an accountant, you don’t know this.

I have already explained this

You think you are right

I think you’re claiming a fraud

And accountancy permits that. Just as once it permitted leased assets to be ignored, and that was wrong, now it creates fictional assets and that is at least as wrong

A plane that does not exist is not an asset: period

And I can assure you that historically accounting got this right, and your claim says it has it wrong now

Like other commentators here you have a very shaky view of accounting history and no comprehension that once we had a thing called true and fair as well as prudence, which certainly did not permit a company to claim it owned an asset when it did not

And incidentally, I do not believe that the contract you are referring to is as you suggest: none are that simplistic and I made that point with care in my opening comment

I suggest you stop wasting my time

I also suggest that if you were so confident of your view you’d state it publicly: passing off is an issue for accountants

A plane that does not exist is not an asset.

A contract for a plane that does not exist most definitely IS an asset.

I don’t think I’m right here. I know so based on accounting rules which haven’t changed in this regard since the 70s. You have ALWAYS got to account for contractual assets regardless of the delivery date. The only thing that has changed over time is how you provision for the exact amount – and then only in how exactly you discount different things.

It is true and fair to account for a contract where you are obliged to purchase something in the future. It is prudent to do so and discount it at a reasonable rate. It would NOT be true to ignore such a contract which could materially affect a balance sheet just because the item hadn’t hurt been delivered.

Imagine if people didn’t have to account for things just because they hadn’t happened yet. Any future payment could simply be ignored. Miners would love it as they could simply ignore the liabilities associated with mine cleanup. The mortgage market would probably cease to function as by your logic, banks doing the lending wouldn’t be allowed to account for the future payments from the borrower. Because they haven’t happened yet. You see the problem with your claims yet?

I simplified my example as the real contract runs to over 100 pages, plus specification annexes. It doesn’t change the basic argument though. Which is that the contract is a proxy for an asset, and assets must be accounted for.

As for being confident of my view? I am. It is basic accounting and all qualified accountants understand the basic accounting treatment of assets. Except you it seems. I’m stating that publically here. What more do you want me to do. Shout it from the rooftops?

I never said there was no accounting required for a contract to buy a plane

I said it was not accounted for at full value

Or at full value discounted for two years either

Nor did I say full disclosure of the contract was not required: I referred to the capital commitment, which was correct, and what did happen in the 70s, for the record.

What we disagree on is the value accounted for – and that in most cases discounting has much to do with this. Some fixed financial obligations may be exceptions. But I stress, may be.