The following comes straight from the Tax Justice Network and is important enough in my view to reproduce in full. I should declare that I directed the first version of this Index but was not involved in any way in this one:

Today the Tax Justice Network launches the 2015 Financial Secrecy Index, the biggest ever survey of global financial secrecy. This unique index combines a secrecy score with a weighting to create a ranking of the secrecy jurisdictions and countries that most actively promote secrecy in global finance.

Most countries' secrecy scores have improved[i]. Real action is being taken to curb financial secrecy, as the OECD rolls out a system of automatic information exchange (AIE) where countries share relevant information to tackle tax evasion. The EU is starting to crack open shell companies by creating central registers of beneficial owners and making that information available to anyone with a legitimate interest. The EU is also requiring multinationals to provide country-by-country financial data.

But these global and regional initiatives are flawed and face sabotage by lobbies that have already weakened them. Secrecy-related financial activity risks being shifted to other areas such as the all-important trusts sector, where no serious action is being taken despite promises made by the G8 in 2013, and shell companies, where many secrecy jurisdictions such as Dubai, the British Virgin Islands or Nevada in the U.S. are refusing to open up.

Crucially, even in those areas where there has been progress, developing countries are largely being sidelined: OECD countries are the main beneficiaries.

Our analysis also reveals that the United States is the jurisdiction of greatest concern, having made few concessions and posing serious threats to emerging transparency initiatives (see box). Rising from sixth to third place in our index, the US is one of the few whose secrecy score worsened after 2013. Switzerland stays at the top of the index and for good reason: despite what you may have heard, Swiss banking secrecy is far from dead, though it has curbed its secrecy somewhat. The United Kingdom also remains a huge concern. While its own secrecy is moderate, its global network of secrecy jurisdictions — the Crown Dependencies and Overseas Territories — still operate in deep secrecy and have, for instance, not co-operated in creating public registers of beneficial ownership. The UK has failed to address this effectively, though it has the power to do so[ii].

The progress: a scorecard

Since the global financial crisis emerged in 2008, governments have sought to curb budget deficits by cracking down on offshore corporate and individual tax cheating and financial crimes by the world's wealthiest citizens. Campaigners have shown them the way and the sea change in the political climate has been remarkable. Progress has come in three main areas.

- Twelve years ago the tax justice movement created country-by-country reporting (CbCR), a measure that can shine a light on multinationals' tax schemes by forcing them to break down their financial activities for each country where they operate, including tax havens. They told us CbCR would never happen: it is now endorsed at G20 level and the first schemes to implement it are in place. However, we are concerned that CbCR cannot work unless the information is made publicly available.

- Just four years ago they laughed at us for pushing the concept of automatic information exchange (AIE), where countries routinely share information about each others' taxpayers so they can be taxed appropriately. AIE is now being rolled out worldwide (see box).

- They said we at TJN were crazy to contemplate public registries of beneficial ownership (BO), to crack open shell companies and ensure that businesses, governments and the public know who they are dealing with, and to provide the basis for effective AIE. Beneficial ownership registries are now endorsed at G20 level: we now need a big political push to make them a reality and bring this information into the public domain.

Of these areas most progress has been made on AIE, with several schemes emerging (see the box, above). Though the G20 had mandated the OECD to create a country-by-country reporting standard, what it came up with has fallen well short, victim of heavy lobbying behind the scenes by U.S. multinationals in particular. Finally, the UK has passed legislation to create a public register of company beneficial ownership information, and the EU has required all member states to make beneficial ownership information available to anyone with a legitimate interest. However, little progress has been made towards creating an effective form of public registry for offshore trusts.

(Read more about progress in these areas here; also see this on why we need public registries as well as automatic information exchange.)

These broad changes are welcome, and we are pleased to see the EU leading the way: even some of Europe's historically worst secrecy jurisdictions, such as Luxembourg and Austria, are engaging.

The EU's leadership role, however, is called into question by recent resistance, spearheaded by Germany, to block public access to CbCR data and prevent expansion of CbC reporting beyond the banking and extractives sectors. (Read more about the current EU-level negotiations here.)

Almost all of the progress to date has arisen from public pressure. To counter the lobbies that constantly seek to undermine progress, sustained political grass roots pressure is indispensable.

The backsliding

Yet huge problems remain.

None of these initiatives take the interests of developing countries sufficiently into account. They haven't been centrally involved in setting the rules, and most will see little if any benefit. (Note, too, that secrecy is just part of a wider charge sheet against tax havens, as the box above explains.)

Meanwhile, even progress to date is under threat:

- Private sector ‘enablers' and recalcitrant jurisdictions like Dubai and the Bahamas are beavering away finding exclusions and loopholes, being picky about which countries they'll exchange information with, and simply disregarding the rules.

- The United States' hypocritical stance of seeking to protect itself against foreign tax havens while preserving itself as a tax haven for residents of other countries needs to be countered. The European Union must take the lead here by imposing a 35 percent withholding tax on EU-sourced payments to U.S. and other non-compliant financial institutions[iii], in the same way as the U.S. FATCA scheme does; and this should become global standard practice.

- The UK has been playing a powerful blocking role to protect its huge, slippery and dangerous trusts sector, probably the biggest hole in the entire global transparency agenda. See below for more details.

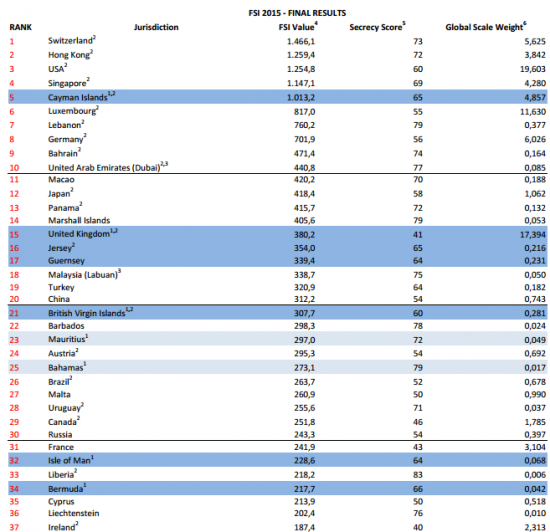

The top end of the ranking

Note: those highlighted in blue are connected to the UK.

The next section gives a brief description of the biggest players in the secrecy world today.

FSI 2015: the big players

Switzerland, the grandfather of the world's secretive tax havens, remains a massively important player in the secrecy world today and is rightly at the top of the 2015 Financial Secrecy Index. It has made some concessions recently to its iron-clad secrecy laws, under strong international pressure, but it has been a laggard relative to some other big players like Luxembourg, and its aggressive and apparently illegal pursuit of secrecy-breaking whistleblowers highlights the strength of the Swiss secrecy lobby. It has committed to the OECD's global-level Common Reporting Standard (CRS) of automatic information exchange, but even then it will start implementing it only in 2018, later than many, and it has said it will be selective about which countries it will share information with. Meanwhile, Swiss secret bankers are shifting their focus away from OECD countries towards building market share in some of the world's more vulnerable and badly governed developing countries, which will therefore continue to suffer Swiss-sanctioned élite looting.

The United States, which has for decades hosted vast stocks of financial and other wealth under conditions of considerable secrecy, has moved up from sixth to third place in our index. It is more of a cause for concern than any other individual country — because of both the size of its offshore sector, and also its rather recalcitrant attitude to international co-operation and reform. Though the U.S. has been a pioneer in defending itself from foreign secrecy jurisdictions, aggressively taking on the Swiss banking establishment and setting up its technically quite strong Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA) — it provides little information in return to other countries, making it a formidable, harmful and irresponsible secrecy jurisdiction at both the Federal and state levels. (Click here for a short explainer; See our special report on the USA for more)

Though the United Kingdom isn't in our top ten, it supports a network of secrecy jurisdictions around the world, from Cayman to Bermuda to Jersey to the British Virgin Islands, whose trusts and shell companies hold many trillions of dollars' worth of assets. Had we treated the UK and its dependent territories as a single unit it would easily top the 2015 index, above Switzerland. The UK has prodded its offshore satellites forwards in the area of AIE, but has failed to force them to create public registries of beneficial ownership, despite having the power to do so[iv]. In the all-important area of trusts, it has played a central role in blocking progress, in stark contrast to its more amenable stance on shell companies. (See our short explainer “The British Connection” and read our new special report on how the UK became such a major player in the offshore secrecy world.)

Hong Kong, in second place, remains a jurisdictions of great and growing concern. It hasn't signed the multilateral agreement to initiate automatic information exchange via the CRS; it has a problematic record on corporate transparency; and unlike European countries it appears to have little appetite for country-by-country reporting or for creating registers of beneficial ownership. China's control over Hong Kong has shielded it from global transparency initiatives, and it still allows owners of bearer shares — vehicles for some of the world's worst criminal activities — to remain unidentified. (Read about the history of the offshore financial sector in our special report on Hong Kong.)

Singapore, in fourth place, poses many of the same threats that Hong Kong does: a lack of serious reforms to its corporate secrecy regime; a lack of interest in CbCR or in creating public registries of beneficial ownership. Yet Singapore has probably been somewhat more serious than Hong Kong in terms of seeking to enforce its own laws and curtailing some of its worst excesses. (Read about the history of Singapore as a tax haven in the special report.)

Cayman is ranked fifth in this year's index, on account of its huge offshore financial services sector and a fairly high secrecy score. Yet Cayman's score has improved markedly since our 2013 index, not least on account of its having engaged with the CRS and being one of only 14 “first mover” jurisdictions to ratify the multilateral agreement for the CRS and agreeing to start exchanging information by 2017. Still, Cayman retains many secrecy features: not least a law which can put people in jail not just for revealing confidential information, but merely for asking for it. (Our in-depth Cayman report and offshore history explains more.)

In 2013 we called Luxembourg the “Death Star of financial secrecy inside Europe,” partly because of its aggressive past moves, in partnership with Switzerland, to undermine EU transparency initiatives. Yet Luxembourg is among our greatest improvers and has dropped from second to sixth place in our index: its secrecy score has improved by an unmatched 11 points to 55. Our Luxembourg special report explores these changes and probes the role of former Prime Minister Jean-Claude Juncker, now president of the European Commission.

Lebanon's position in seventh place on our index, unchanged from last year, may surprise some people. Yet its position is well-deserved, resulting above all from its having a very high secrecy score, indicating a country that has resolutely failed to engage in the fast-evolving international climate on financial transparency. It has failed even to commit at all to exchange information under the global CRS standard. Our Lebanon special report digs into the unique offshore history of the Lebanese financial centre.

Germany's ranking in eighth place is also likely to surprise. But those in the know, however, Germany's position is deserved. Our special report on Germany explains that Germany is a safe haven for illicit money from around the globe, and exhibits great laxity in a whole range of areas related to illicit flows. In his September 2015 book Tax Haven Germany, TJN researcher Markus Meinzer calculated that in 2013 non-residents held €2.5 - 3 trillion in tax exempt interest-bearing assets in the German financial system, in conditions of secrecy.

Bahrain is one of the most secretive jurisdictions in our Top 10. With an offshore financial centre that caters mostly to Arab countries and the sub-region, it has so far completely ducked out of committing to the CRS and automatic information exchange. It is, except for Cayman, the only jurisdiction in our Top 10 to have no income taxes: a powerful driver of often nefarious offshore activity. It complements this with strong secrecy for legal entities such as shell companies, and offers a special variant of a trust, known as the waqf. (Read more about Bahrain in our special report.)

With a high secrecy score of 77, Dubai is another recalcitrant that has resisted pressures for reform, and has long attracted large quantities of criminal and tax-evading money from Asia, Africa and further afield. Private sector practitioners stress that Dubai stands out above many other jurisdictions in terms of its lack of interest in transparency, and the laxity with which its offshore sector is supervised and regulated. Our special report on Dubai gives more.

John Christensen, Executive Director of the Tax Justice Network, said:

“The United States dealt global financial secrecy a devastating blow by forcing strongholds such as Switzerland to open up. But after this blistering start in efforts to protect itself, it is backsliding by failing to provide information in the other direction: refusing to participate directly in global transparency initiatives such as the multilateral automatic information exchange and, inexcusably, lobbying to block public country by country corporate reporting. The USA must finally overcome its historically rooted opposition to reasonable tax data sharing with its trade and investment partners.”

Liz Nelson, a director of the Tax Justice Network, said:

“None of the reforms we've seen would have taken place without pressure from civil society and the streets. G7 and G20 leaders will do nothing unless pushed from below. So it's essential to keep up the pressure, especially on matters such as implementing public disclosure of company ownership and, crucially, of trusts.”

Markus Meinzer, leader of the Financial Secrecy Index project, said:

“Germany is a growing menace for financial transparency. Germany has been playing the key spoiler role within the EU with respect to public financial transparency. While France and other EU countries are pushing for further tangible reforms, Germany is strongly resisting these pressures.”

Rosie Sharpe, campaigner at Global Witness, said:

"David Cameron is hosting an international anti-corruption summit in 2016. The UK bears responsibility for ensuring the good governance of its dependent territories, which lie at the heart of the global provision of financial secrecy. For the summit to be a success, the UK government must require these places to open up."

Luis Moreno, coordinating committee member of the Global Alliance for Tax Justice, said:

"These new findings confirm welcome progress in beginning to reduce financial secrecy at the global level - but that stands in stark contrast to the distribution of benefits, which are flowing overwhelmingly to OECD members while most developing countries are excluded. Despite the bold promises of the G8 and G20, what the OECD has delivered thus far on information sharing and on corporate transparency has actually worsened the global inequalities in taxing rights. This is why we need a new international tax body that includes developing countries to decide on the international tax rules."

Tove Maria Ryding, tax coordinator at Eurodad, said:

“The EU took a crucial step forward when deciding that the true beneficiaries of all EU companies must be registered. A few EU countries went even further and took the important decision to make their registers fully public. Other countries should follow EU's example, but the EU must also ensure that the ambition is not lost in implementation. It is crucial that the new directive is turned into strong national laws, and that new secrecy structures, such as secret trusts, are not set up in the EU to replace the old ones.”

Thomas Piketty, Economist, author of Capital in the Twenty-First Century, said:

“TJN has done more than any other organisation to put fiscal justice at the center of the policy agenda. Tax issues should not be left to those who want to escape taxes! Change will come when more and more citizens of the world take ownership of these matters. TJN is a powerful force acting in this direction.”

FAQs

Note: some of these explainers are based on the 2013 index, but the analysis is basically unchanged.

- What is a secrecy jurisdiction? Click here.

- How is the FSI constructed? Click here.

- What are the different ‘flavours' of secrecy? See here.

- Why has my country's ranking changed? See here

- Are the UK, USA, and Germany really secrecy jurisdictions, or tax havens? Yes they really are: as our special reports on each country explain.

- Is Swiss banking secrecy dead? No! See our Swiss special report (attached)

- Why is financial secrecy harmful? See our sections on markets, corruption, and human rights, for example.

- Who creates all this secrecy? Click here.

[i] Compared to the FSI 2013, the average secrecy score has fallen from 66 to 60. However, the methodology has tightened slightly since the 2013 FSI: this — all other things being equal - would mean a general worsening of secrecy scores. So the improvement is slightly better than the numbers would suggest. Six of the Top 10 countries have improved their secrecy scores.

[ii] The Crown Dependencies and Overseas Territories are controlled and supported by Britain. The Queen's head is on their stamps and banknotes; she appoints top officials, and legislation is approved by the Privy Council in London. The relationship is commonly misunderstood, however. When it suits them — such as when they are pressured to reform their worst secrecy-related laws — they assert that they are independent and that Britain cannot force them to change. In fact, though the relationship is complex Britain can force them to act, if sufficient political will can be found. (In 2013 we wrote to the Queen to ask her to intervene.)

[iii] The U.S may claim that via FATCA its financial institutions already provide reciprocal data. But, as this article explains, they do not.

[iv] See Endnote ii.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

So Germany is more of a tax evaders Paradise than the UK?

Don’t think you will be pushing that very far, if the biggest Country in the EU helps tax avoiders then maybe the UK needs to leave before bad habits spread?

The issue relates in part to the fact tgat bearer bonds are still in widespread use in Germany