I have recently written about Jolyon Maugham, a tax barrister who is having a real and positive impact on campaigns against tax avoidance.

I think it's time to draw attention to another tax barrister who is, I think, also going to have a big impact on this issue. He is David Quentin. As he says of himself:

David Quentin is a barrister specialising in UK and international tax law. He has worked at leading UK law firms Allen & Overy LLP and Farrer & Co LLP, and has extensive experience advising on corporate and private client tax risk. He is also a Senior Adviser to the Tax Justice Network.

David is a barrister very firmly in the tax justice camp, and that's important because what he brings to this issue are his distinct skills and analytical ability. These are very firmly revealed in a new paper he has written under the title 'Risk Mining the Public Exchequer'. This is, I think, a very significant contribution to debate on a vital issue, which is just what the difference between tax advice, tax planning, tax avoidance and aggressive tax avoidance is.

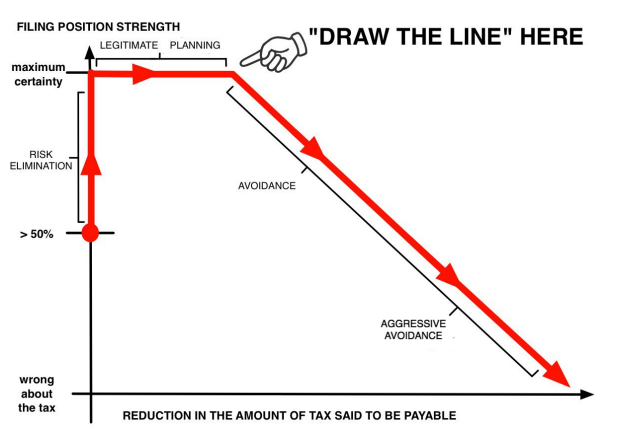

I strongly recommend reading the twenty page paper as a whole, but offer one diagram as a taster:

The vertical axis shows tax uncertainty; the horizontal shows tax saving.

David's argument is that a tax adviser's role can be defined in three ways. The first is to move the tax payer from a position of uncertainty to one that has as much certainty as possible. His example is in clarifying whether a person is self employed or employed, which requires the adviser to offer opinion on how a contract can be created which meets the desired intention. An obvious alternative might be in offering advice on the correct VAT status of a transaction. In both cases the intention is not to reduce a tax bill but is, instead, to deliver tax certainty so that the taxpayer knows where they are with regard to the law and then applies it correctly. The taxpayer's position moves up the vertical axis as a result. This is, of course, a thoroughly worthwhile activity.

Having achieved that goal the tax adviser can then suggest certain courses of action to the tax payer that have no risk attached to them but which have the ability to reduce their tax bill. This is possible, of course. Contributions to pensions can attract tax relief. Allowances are due for capital expenditure and people need to know that. ISAs are completely consistent with the law. There is absolutely no risk in making use of these options, and many others, available in law. As a result it is possible to give tax advice and reduce a taxpayer's liability and not increase their tax risk. This is represented in David Quentin's diagram by movement to the right along the top horizontal red line.

But then, as David says:

[T]here will come a point when our filing position starts to get weaker again. There are further tax savings to be obtained but they cannot be guaranteed, or at least they cannot be said to be as likely to succeed as the filing position we would have if we did not implement the advice. New tax risk factors are being introduced, and the relative certainty in the modalities of the verbs has reversed. It is now the tax advice which produces an analysis that “might” succeed, whereas if we do not implement the advice the tax “will” be payable.

The concept of the 'filing position' is important here and is not, perhaps, explored by David as much as he might. It has to be remembered that a taxpayer 'self assesses' in the UK. That means that they tell HMRC what they think their tax position is. This is their 'filing position', and they have a choice to make on it. They can opt for certainty, or they can adopt a riskier position where the outcome of their claim is not certain. Once they do that they enter the downward slope towards the right hand side of the diagram. This, David argues, is where tax avoidance begins.

It is adopting this position of risk to potentially reduce a tax bill (it can only ever be 'potentially reduce' precisely because the outcome is uncertain in these situations, with that uncertainty increasing as one descends the right hand slope) that creates the ethical dilemma in tax avoidance in David's opinion, and I agree with him.

I once ran a firm that sought only to reduce taxpayer risk and offer advice within the top horizontal range of possibilities. It was, and is, my belief that firstly tax risk was not worth taking precisely because there was risk which created uncertainty, and secondly, that there were better things for me and my client to always undertake to improve their net income then take this risk. In other words, I, and they, were better off increasing their pre-tax income than reducing their tax liability on a reduced sum. This is a factor almost never taken into account in this equation, but which is relevant because time available to take action is always an active constraint in any adviser / client and in any real time business decision taking process.

David does however, quite reasonably, not take that point but does take another, which is that:

Eventually the tax advice will be so aggressive that the chances of success upon tax authority challenge hit the bottom. The anti-avoidance law definitely applies, or the statutory interpretation relied upon cannot possibly be correct, or the commercial reality of the transaction is such that the formal analysis is hopelessly unsustainable, or the factual assertions are never going to withstand forensic scrutiny, or the accounting assumptions are false. Our filing position is, in effect, a lie. And if it is challenged it will fail. We are at the far end of our journey along the tax advice risk curve.

It is at this end of the spectrum that many recent tax schemes have operated, and failed. But before that situation is reached David thinks there is risk, which starts at he point where the downward slope begins and activity moves from legitimate tax planning to the risk assumption inherent in tax avoidance. Of this he says:

Admittedly at first the risk differential is small, but it is appreciable to a professional because pointing out tax risk, or (more accurately) identifying tax risk factors which are introduced by a given structuring option, is a tax adviser's job. Indeed if a tax adviser fails to identify a tax risk factor which is introduced by a given structuring option and that risk eventuates, the adviser has in principle exposed herself or her firm to an action in professional negligence.

In saying this David confirms something I have always suggested, which is that the competent tax adviser always knows when there is ambiguity in their advice because they have to disclose it to their client. If they do not they are professionally reckless. So, for example, running a trade as a limited company with one dominant client and taking the reward as dividends will always be tax avoidance because there is a risk that IR35 rules might apply. It may be deemed an acceptable risk to the adviser and client but there is a risk nonetheless. That has implication. As David puts it:

Deliberately creating tax risk is deliberately creating the possibility that your filing position understates your tax liability. Between not understating your tax liability (“legitimate tax planning”) and understating your tax liability (“evasion”) lies a category of behaviour which is deliberately bringing about the possibility that you might have understated your tax liability, and this is the category of behaviour which I propose to label “avoidance”.

There is then, according to David, an answer to the question of whether there is a dividing line between legitimate tax planning and tax avoidance. That is at the point where the line in David's diagram begins to turn downwards and tax risk is assumed. There is also an answer to the question of “what is the ‘right' amount of tax?” As David puts it:

The “‘right' amount of tax” is the amount of tax you pay if you implement tax advice which eliminates risk or is risk-neutral, but do not implement tax advice which actually creates tax risk.

This then gives rise to the question of what, then, is so wrong with the deliberate creation of tax risk? David answers this question by suggesting that the current view of avoidance is wrong, saying:

Avoidance is usually defined as reducing tax payable by legal means, but in fact the opportunity that is increased as you head down the avoidance section of the tax advice risk curve is the opportunity to not pay tax which is legally payable. This is because wherever there is tax risk there is a chance that (a) the filing position is wrong and that extra tax is payable, and there is also a chance that (b) the filing position is not going to get challenged (or that the challenge fails for want of evidence, or fails for technical or procedural reasons).

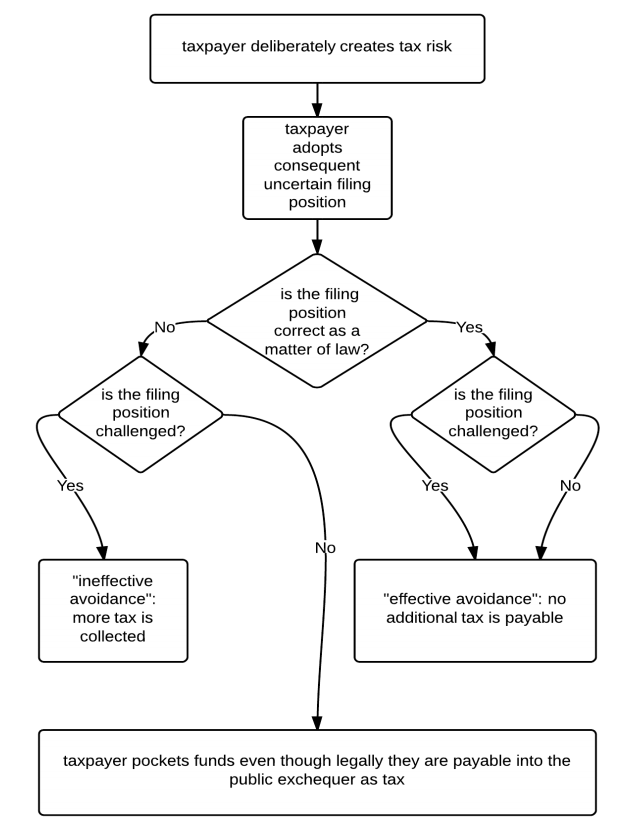

This is a very different view of tax and avoidance. Tautologically David's first observation has to be correct: if there is tax risk in the taxpayers position it must follow that there is extra tax payable. At least as interesting, therefore, is the second idea, which is the risk factor of being ' found out'. David explains this in a flowchart that looks like this:

The importance of this flowchart is best expressed by David, who says:

The innovative feature of this apparently simple flow-chart is that I put the questions in the correct order. The mistake invariably made in this context is to treat the process of tax authority challenge as itself determinative of whether or not a liability to pay additional tax arises. This treatment reflects a fundamental error of analysis. Except in the very rare case of retrospective anti-avoidance legislation, the liability is anterior to the processes of enforcement.

In other words, tax avoidance always embraces the risk that the wrong amount of tax might be paid, and this is true whether or not the Revenue challenge the position. There is, therefore, always the possibility that the wrong amount of tax might be paid at cost to the rest of society. And this, is precisely why David says that tax avoidance has attracted the moral opprobrium that it has. This is because:

in fact any deliberate creation of tax risk, however small its shortfall as compared with maximum filing position certainty, is a deliberately-created opportunity to not pay tax which is legally payable. That opportunity is created at the expense of taxpayers generally, and is therefore anti-social conduct deserving of the opprobrium attaching to the phrase “tax avoidance”.

I think this is absolutely right.

There is, of course, more to David's argument than I have noted here, but I think its significance is that it answers some questions in a deeply logical way that will be hard for many to refute, and it explains why tax avoidance, which is so often claimed to be legal, does in fact create risk that many people find offensive. In achieving those aims this is a major contribution to the debate on tax avoidance, the ways we should think about it, and most importantly, what we should do about it.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

This is excellent Richard. I think the point he/you make about the ORDER of the flow diagram is key.

I can imagine the right-wingers arguing that the ‘good’ of avoidance is therefore to create ‘more certainty’ by finding out (testing) where the boundary lies. i.e. determining what they can get away with following legal challenge. This in their minds would therefore potentially extend the ‘maximum certainty’ line further to the right.

But Quentin shows that this is backwards, because first they would have to decide to attempt to not pay tax legally due, at a cost to the rest of society. Their very first step is the decision to attempt to avoid, it is only after that they could possibly know whether it is ‘legal’ or not.

Agreed!

There is an old chestnut you have dupg up again in the phrase:

“So, for example, running a trade as a limited company with one dominant client and taking the reward as dividends will always be tax avoidance because there is a risk that IR35 rules might apply”

Margaret Hodge has of course been very critical of these arrangements. It has also reared its head today with the news about Andy Burnham’s advisor’s arrangement. You yourself have been attacked down the years for an old article you wrote about setting domestic help up with personal service companies.

I personally would go further than your statement above and say that, regardless of IR35 rules, describing what is clearly an employer/employee relationship as hiring a company to provide services is clearly a mis-statement of reality and is tax avoidance.

Do you accept, with the passage of time, that your article was in fact a tax-avoidance instruction?

I have long explained, if you’re not aware of it, that the whole purpose for writing that article at the time was to expose a tax planning scheme that was then being explained as a good wheeze on the tax lecture circuit, and which I did not like and would never have recommended to a client, and did not.

The article was written well before the days of DOTAS and at a time when the Revenue tended to catch on with these things only after a significant time delay. The advantage of the article was that it gave rise to an almost immediate announcement that the scheme would be outlawed, which was exactly what I hope for.

I would never campaign that way now, and admit, in retrospect that the article does not look that great, but it achieved a result, and within the constraints of the time (no blogging, no DOTAS, no other ready means of publicity) it worked.

Thank you Richard. Do you also agree that the scheme getting the headlines today looks bad? I am per tiara aggrieved that politicians can condemn tax avoidance whilst actually practicing it at the same time.

This does not look good to me

Very interesting stuff, Richard. I’ll get to read the full report later. But I have one question in the meantime. Given what we know of the operation of the large business unit at HMRC and the general attitude and approach of HMRC to large businesses, and especially multi-nationals (what Richard Brooks refers to as ‘relationship taxing’), isn’t it the case that the extent and degree of risk differs depending on what type (form) of taxpayer you are?

Furthermore, and related to that, what we also know is that if the ‘filing position’ of an MCN is challenged and ‘ineffective avoidance’ is the outcome then the penalty/payment is far less onerous, relatively speaking, than that levied against a small trader. Again, that has a bearing on risk (or perceptions of risk at the least) doesn’t it?

Ivan

You are right

The risk does differ – not least because large business can always get an opinion if they want it

Smaller business cannot

So risk mitigation is also different in each case, favouring big business too

Richard

Not sure I agree.

I was thinking more that the risk is the same for big and small businesses. But it’s just that bigger business has more opportunity (because it can pay ‘the boys’) to be better informed as to the level of risk it is taking on.

I am not sure an ‘opinion’ changes the risk (it may give more opportunity to argue lower penalties if it goes bad I guess but that’s all) it just gives the taxpayer more information on the risk being udnertaken.

Big business has much better access to HMRC. That is the point I was making. If they wish to mitigate risk they have the perfect opportunity to do so which is not available to anyone else.

OK yes, I see what you are saying. That is true. If I have an uncertain tax position in my company I can eitehr speak to an adviser or talk to my CRM – the latter of course reduces risk a lot and is clearly not an opportunity open to me in my personal capacity

Is there a theoretical possibility that HMRC could make a mistake? So if for example a business deliberately did *not* create tax risk, but this was challenged in error by HMRC, would a business have avoided tax?

Or another way – has a business engaged in Tax avoidance if HMRC subsequently act in error? Or is the very fact of a challenge proof positive of avoidance?

The Courts exist to correct for that possibility

Right. Of course. So a business can do the right thing and be wrongly accused, but the Courts will correct for that and we are all clear that no avoidance happened.

So the flow diagram needs to change then. Think it through from the perspective of someone who did *not* attempt to avoid tax and was subsequently wrongly accused (and then rightly acquitted). The flaw will become obvious.

There is no flaw

You are seeking an aberration that this is not considering

And a situation that the flow diagram does not cover and does not intend to cover

It only covers where there is the intent to avoid

You say there was none so it is not in this space

You are right – the flow is not considering the ‘aberration’ where HMRC make a mistake.

This is a significant contribution to the debate. I am glad that he highlights the existence of being ‘found out’. as a significant risk factor. The defence of ‘not being challenged’ = ‘HMRC acceptance’ is no defence at all.

This of course brings a new and helpful narrative to the issue of HMRC staff numbers and their ability to police the system. It’s about time being able to ‘play’ HMRC became a thing of the past.

Agreed!

I have to say I do like this approach and the diagram is a great way to look at it. I may use that.

I have only 1 thought to add to this debbate in that the risk graph does not sem to consider the situation where there is genuine uncertainty in what the tax law actually means. You could file under what is a gebuione viewpoint and lose in court – are you then conciously tax avoiding?

There would be uncertainty in that case

The wise option is to go down another route

Usually that is possible

I think it is great when a some senior tax lawyers are seen to support the right and moral way of conduct in tax affairs. The trolls seem to be kept at bay a bit too !

I think it is good too…but equally I’m willing to bet that Mr. M. could find an equally skilled tax barrister that could argue exactly the opposite and both barristers could find mountains of paperwork to support each point of view.

I would not be so inclined

I think this is right

the way businesses and politicians spin it, you would think that all avoidance falls within the ‘legitimate planning’ part of the diagram. more likely, most avoidance IS illegal, it’s just that the HMRC doesn’t have the resources to prove it.

I don’t think that is what is being said

In fact some avoidance is legal (there are court decisions to prove that) but just because something is legal doesn’t mean it’s not avoidance.

The point David Quentin is making is that it’s the decision at the top of his flowchart — i.e. where the taxpayer adopts an uncertain filing position with the intention of reducing the tax bill and knowing that the uncertainty is due to their taking a risky position — that is the point where you determine whether there is avoidance or not.

The fact that the scheme/plan turns out to be in line or out of line with the law is irrelevant, it’s the original intent that is important — in his terms it’s taking the position per the scheme/plan knowing it is increasing the risk that your stance is uncertain that indicates tax avoidance has taken place.

You are of course right that there is a lot of spin around suggesting that if it turns out to be legal then it isn’t avoidance, but David Quentin is pointing out that is not the decisive factor. He cleverly turns the typical decision making tree around to make the point it is the decision at the top — i.e. the decisions and actions taken by the taxpayer – rather than the result achieved in court that indicates tax avoidance.

It’s only when you get to the very bottom box that you get to a position where the taxpayer has undertaken what I think of as pure ‘illegal’ avoidance – And this is of course teh bit where we arrive at a bad result due to lack of resources within teh tax authority … although from the full paper we arrive there sometimes becasue the tax authority is unwilling to challenge due to fear of losing.

Ps — Don’t get me wrong, I’m not advocating that ‘legal’ (’effective’ on the flow chart) or ‘ineffective’ avoidance is Ok but it has to be clear (for me at least) that (unfortunately) some avoidance is ‘legal’ and certainly not all avoidance is ‘illegal’.

PPs — As I say I like the concept. I need to reread around paragraphs 45 onwards again as I’m not sure I got that properly yet and I especially want to understand and be able to explain para 46 properly as I think a ‘hub’ may rear it’s head in our company again soon and if (as last time) it comes with some dodgy tax saving idea attached to it, I want to knock it down again and be able to properly elucidate my reasoning – last time it was just on the basis it didn’t ‘feel’ right ïŠ

You are right – not all avoidance is illegal

But if still may not work and so involve tax risk

My logic was that if it didn’t work it would be because it was refuted by the tax authority or refuted in court. Hence not in line with the law and hence ‘illegal’.

If the avoidance is found to be in accordance with the law then it is ‘effective’ and by definition ‘legal’.

But as you say that doesn’t alter the fact that the initial decision to enter into the scheme/plan/whatever is taking a risk, because at that point you have no certainty – which is the crux of the argument in the paper — and hence it is avoidance.

This is a great way to look at it and it occurs to me that one of the stated objectives of our global tax department is to minimise tax risk. But I am not sure anyone has ever really buttoned down what that really means and how we identify teh boundary. We are incredibly conservative as a whole and do achieve that but I think using the thought process that David outlined will help clarify that thought process better and will be a good thing to bear in mind when considering options that have tax consequences.

As the group grows we get more, now how shall I put this …, dealings with our advisers and more ‘suggestions’ as to how we might change things. David’s idea is very helpful in identifying where the boundary lies. 🙂

Good to know

Why not tell him?

Richard

It will be raised don’t worry 🙂