I have argued for longer than I probably care to remember that the last thing we need in our economy right now is a balanced budget. When and if we have full employment, higher productivity and a confident business sector that is investing heavily and exporting at considerably higher levels than at present I will change my mind: right now we are so far from that situation that a government surplus makes no sense, in theory or in practice.

To complicate consideration of the issue I have also argued that, as a matter of fact, having a balanced budget is something no government can expect or promise to deliver. There is good reason for this. As I have argued in more depth here (and many other places):

The reason is that there are, in macroeconomic terms four sectors in the economy and they must balance. The first is consumer spending. If consumers borrow more to increase spending then someone must lend it to them, or borrow less, as a matter of fact. That person who must borrow less might be business, who might invest less as they borrow less to compensate for more consumer borrowing, or it might be net overseas trade, or it can be the government. But the point is that the net lending and borrowing of these four sectors, consumers, business, overseas and government, will always balance, as a matter of fact.

So, frustrating as this might be to a politician who wants to appear to be in control of the destiny of their government and the state, the fact is that they have remarkably little control over how much they will borrow. If consumers insist on saving, as does business, and trade is running a deficit, (which in effect means foreigners are saving in Britain) then as a matter of fact the government will run a deficit whether it likes it or not. And there is nothing, bar stimulating business investment, exports, or consumer borrowing that they can do to change this.

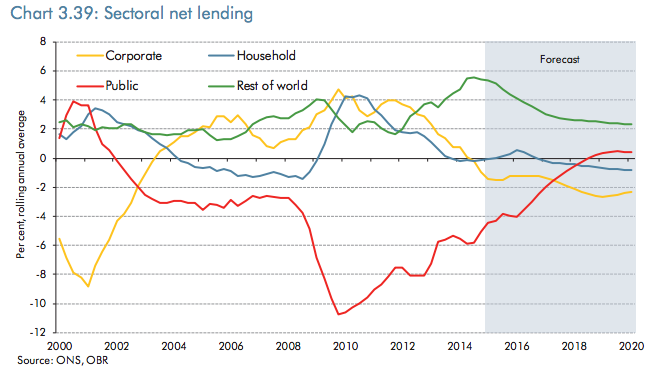

Let me put this in context. These are the sectoral balances and forecasts for them as per the March 2015 budget data:

All of these balances add to zero. And, as is clear some factors make it very hard indeed to achieve a balanced budget, let alone a budget surplus. The only time it happened in this period, from 2000 to 2002, it was only really possible because of the enormous corporate borrowing during the dot.com era. That Labour kept the deficit under reasonable control from then on was, as is widely known, because consumers borrowed during this period to compensate for the fact that after the dot-com crisis business simply stopped net borrowing - which is why they have ended up with what Gillian Tett of the FT has called 'zombie piles of cash'.

And throughout this period note the enormous impact of the 'rest of the world'. Because of trade and investment flows flows the 'rest of the world' has persistently saved in the UK throughout this period. The result has been that even if business and consumers decided to just lend and borrow from each other and always themselves equalled their flows out to zero (which is very unlikely to happen, but is technically plausible) the UK government would have, for this one reason of the overseas flows, have had absolutely no choice but, as creator of the UK currency, to have run a deficit throughout this period to meet the demand for lending that overseas savers had in the UK and which in that circumstance could only be met by government borrowing. And I stress, there is nothing the government can do about this because, unlike business and households (and the rest of the world when it is stated vis-a-vis the UK) only the government is the creator of currency that can make this equation work. It supplies this currency by running deficits. As a previous post argued, this means it must either create gilts to satisfy the demand for savings products that the actions of others in the economy demands that the government must meet or let reserves at the Bank of England accumulate, but one or other must happen.

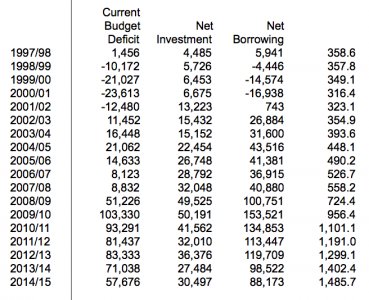

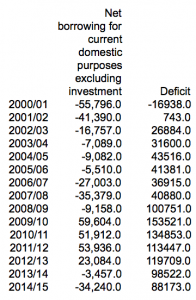

In that case the real issue to be discussed when it comes to deficits, as John McDonnell MP, a close colleague of Jeremy Corbyn did in the Guardian recently, is ask just what aspect of the deficit is really being discussed. There are a number of obvious splits within the data to be made to make such discussion meaingful. The first is between current and capital deficits. It baffles me why this distinction is not normally offered when discussing deficits. For the record, this is the data I am using from the June 2015 PSA1 Summary of public finances from the ONS:

The current deficit is anything not for investment, of course. Net investment is government investment in this case, not that for the economy as a whole. Figures are in millions barring the last column which is in billions. This is that data plotted:

But suppose that borrowing to pay for net investment (i.e. cost net of sale proceeds) is charged to a capital account. £444 billion over this period then falls out of current account borrowing. From 1997/98 to 2011/12, when QE ended, the borrowing for capital spending was £350 billion. £375 billion of QE did, of course, pay for all that. In fact, you could argue it looked suspiciously like PQE did actually take place, retrospectively, for the entire cost of state spending for that period. If PFI had been added in it would have been less, but the point is QE cancelled all that investment spend: it has now gone from the state balance sheet as debt and is now paid for with much cheaper reserves. So, we have already, in effect done PQE and still met the demand for savings.

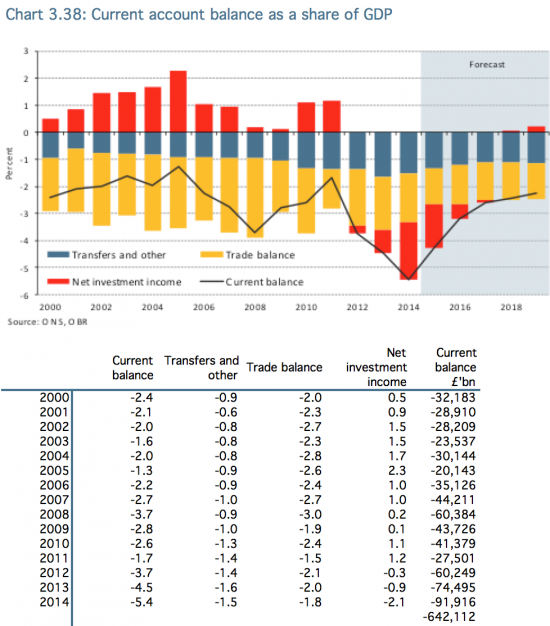

What about the rest of the deficit? Go back to the sectoral balances and look at this data, based on the OBR for March 2015 using historic data for the overseas element of the sectoral balances combined with ONS GDP data to indicate a cash value:

Since 2000 more than £640 billion of deficits have occurred in the UK simply because people from the rest of the world insist on saving in the UK, in sterling and the government had no choice but create the currency they need to let them do so. That effectively meant it had to run deficits for almost all that period for this reason alone. I stress: they had no real choice.

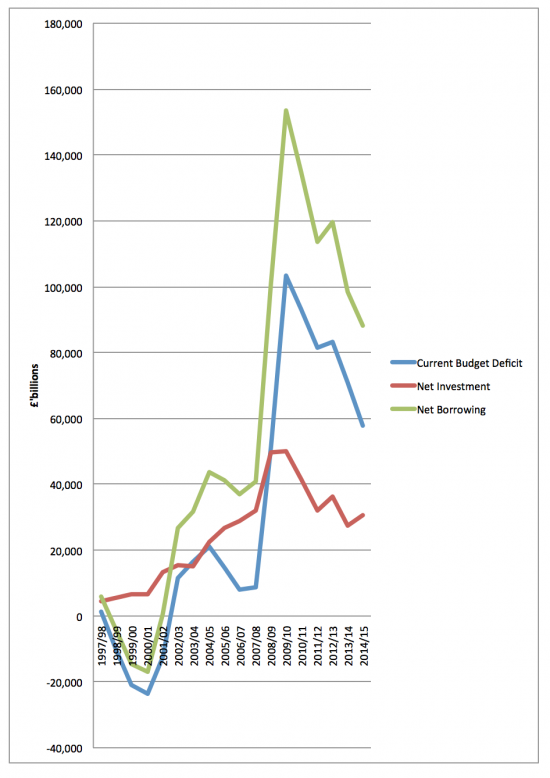

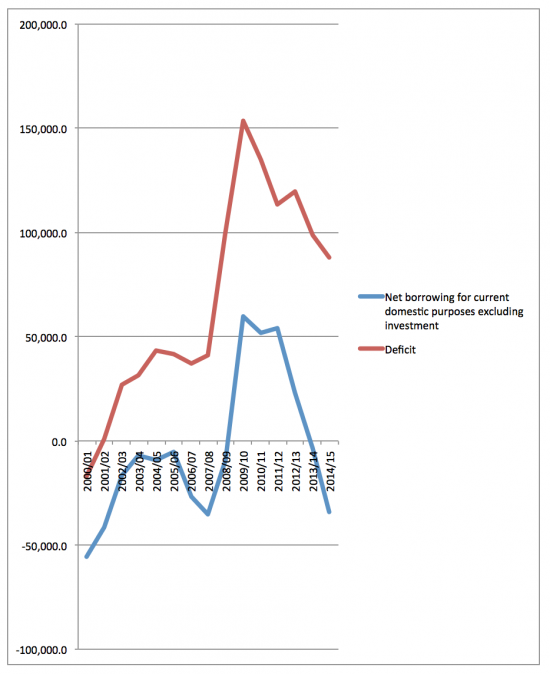

Now compare this data with the data on borrowing and if you exclude borrowing for investment, which it can be argued should be on a separate loan account, and you deduct from the remaining deficit that which had to be created to fuel foreign demand for sterling savings you end up with this data with the reported deficit shown just for comparson:

Which looks like this when plotted:

This implies the UK only ran a deficit to meet current domestic need from 2009/10 to 2012/13. Overall it ran a surplus for this purpose over the period.

Is this a fair way of viewing the deficit? I suggest it is. I also suggest, immediately that this is not the only alternative way of looking at deficit data: I can and maybe will juggle this data in numerous other ways as yet to see what might be useful. But my points are threefold.

The first is that, as I repeat, some parts of the deficit are out of the governments control. This is most especially true of the net amount of foreign saving in the UK in a time of floating exchange rates. This demand for sterling has to be met and the government has to meet it: only it can create the currency to do so, usually in the form of gilts. Not recognising this would be absurd. To also try to eliminate this would be to look a gift horse in the mouth: do we really want to stop people from outside the UK effectively subsidising us, which is exactly what they are doing, at incredibly low interest rates over very long debt repayment periods, with a fair chance that a good part of the debt will be written off by the impact of inflation in the meantime and without foreign currency risk as they are saving in our currency? I suggest not.

Second, it is also absurd to lump together the borrowing for government investment with that to meet current domestic need not funded, in effect, by overseas lenders. This borrowing for investment to be accounted for quite separately. This is borrowing to fund improvements in our national infrastructure. We need this. We should be proud that we make such an investment and want to continue to do so. We should be really worried if it declines - as in real terms it is at present. That puts our well being at risk. We need a way to separately and clearly identify this spend to make sure it is properly recognised and managed. No one is going to be surprised that I think this is a role for PQE.

And, thirdly, what's left? Well, as the last graph shows, all too often it is a government surplus, much (but not all of it) happening because of increasing household debt. I am not too sure that is something we should be celebrating, and so there is an issue to consider here and how it is business surpluses that need to be addressed here.

I stress: this is a quick analysis. What I am suggesting though is that the deficit narrative is far too constrained and and that if discussion of the deficit and whether or not part of government activity is to be run in surplus is to take place then we need to be aware of what the surplus is made up of, what elements might be controllable, what parts might be fundamentally useful and essentially suited to a controlled borrowing programme, and how the remaining balances need to be managed to ensure overall wellbeing of people in the country is maximised. And in the process I am saying that the deficit narrative we have suffered to date has utterly missed the point in economic terms and been deeply misleading in terms of its consequences for political economy.

If we're going to have a debt and deficit narrative let us, for heavens sake, make it one that is useful and based on what really happens. That's the least the left should be doing now because if and when we do so the policy implications would be deeply significant.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

The Corbyn camp needs to take this on and be explicit about it. I suspect that Corbyn is still using the ‘balanced books’ myth as a ‘pacifier’ or sop to the vox populi-much better to explain and educate! Hope you can highlight this in the debate.

Excellent.

The very latest sectoral balances is here BTW including Q1 2015:

http://www.3spoken.co.uk/2015/06/uk-sectoral-balances-q1-2015.html?m=0

Thanks

The great thing is that, on the 27th, you will sit down for a discussion with a guy that knows more about this stuff than anyone else on the planet. No wonder the venue is sold out. I’m on the waiting list so should they find a much bigger one I look forward to seeing you there.

I will indeed, metaphorically, be sitting at the feet of Gamaliel

“The current deficit is anything not for investment, of course”

Including training, education and development – which isn’t classed as investment in the national accounts accounting policies.

Since you’ve no doubt spent your career determining what can be capitalised and what has to be revenue, this will be no surprise.

But it may be a surprise to some readers that ‘investment’ is often in the eye of the beholder.

And that is why the distinction between the capital and current budget is largely arbitrary from an economic point of view. Current spending causes second order investment spending to supply the increased demand. There’s no real justification why first order investment is better than second. You need to do enough of both, but no more.

Keynes viewed the budgets separately – for political reasons I think – and Lerner saw no need for it. And as far as I can see that argument has never been resolved satisfactorily since Keynes died.

I entirely agree that the split has discretionary elements

But I am a political economist: the language is key

That is a vital point to make (more on this later)

It is.

PR and marketing works after all.

But you’ve got to be careful, otherwise you restrict yourself so much you end up building roads to nowhere so that things are in the right budget.

And as I’ve pointed out, you can’t do education or training – despite those both being probably the best countercyclical responses.

There’s a substantial risk of a curate’s egg here.

I accept the risk

Richard

Richard, is it fair to say that if corporate surpluses are likely to remain that way (for a variety of reasons) and also the foreign balance, then any move by government balance towards surplus must be met by a move by households towards deficit – and that this is what has been happening? Therefore it is both hypocritical and disingenuous to portray the UK growth story as a major success story. It is the old boom rehashed.

Spot on

With all the dangers

Perhaps government borrowing shouldn’t be called borrowing at all. Since it is not like household or business borrowing at all. If you have the ability to created an unlimited amount of pounds, did you really borrow anything?

Read MMT properly

Trying to run a surplus is dangerous nonsense. There is a reason that we very rarely have a surplus and that is because money raised through tax is nowhere near enough to achieve a balance, therefore we are always forced to borrow the rest.

After the depression in the 1930s the government of the day insisted on a balanced budget and the resulting deflation effectively doubled the debt.

We invest to full capacity THEN we pay down the deficit, and then only if we can do it without causing deflation in the real economy or pass on debt to businesses or consumers.

There has never ever really been a time when austerity alone ever works. It is junk economics and was proved by Keynes to be just that.

This government have borrowed more than all previous Labour governments put together. They have had to borrow in order to stop the bottom falling out of the economy.

It’s time people stopped falling for this “balancing the country’s budget like a household” rubbish.

With as debt-based economy, the debt can only grow, either through public debt or private.

This analytical approach is remarkably interesting and important. Historically, it appears to complete the Post-Keynesian picture that began with the concept of ‘circular & cumulative causation’. Most particularly the link between current account and govt. deficit.

With regard to the “framing” issue though I can understand Corbyn’s caution as most people are not aware of that link – and that includes most economists. This does not necessarily mean that they are all neoliberals or know-nothings who think that govt. is like a household.

Even in Keynesian terms the surplus/deficit question is most commonly thought of as a cyclical issue where a surplus is preferred when inflation is higher and a deficit counteracts the downturn.

Given that is the case, and taking a lateral view, Corbyn’s reassurances may make some sense given that stimulus and deficit would be slowly reduced as growth and increased tax revenues imply that the recovery becomes more & more self-financing (higher GDP, lower debt-to-GDP ratio etc.)Reframing can begin where there is some common ground.

It appears from my reading that many contributors to this blog are highly conversant with the idea of MMT. In conversation they would do well to remember that most people and most economists – even the progressive ones, are not. Some of those ideas will take time to explain. Jeremy Corbyn’s political advisers tread cautiously with good reason.

Many people may also be slow to appreciate the idea that trade deficits are generally OK and rampant mercantilists like the Chinese (or Germans) are doing us a big favour. For most, that idea may work well from a consumer point of view but not from an employment perspective. Besides which, imported deflation is less attractive when home-grown deflation has already taken hold.

Richard, another idea that my require explanation,is your general preference for low interest rates. I may have missed something in your writings but, generally, the link between endlessly cheap private debt, asset-price speculation and the liquidity trap tends to be regarded as a characteristic failure of neo-liberalism.

Is it possible to have permanently low rates and avoid financialisation?

Why would you want high interest rates?

Keynes made the case for not doing so

I can’t see why they need updating

But your words of caution on framing are well placed

I don’t want high interest rates but do have reservations about permanently low (very low) interest.

Irving Fisher was among the first to identify the lure of low interest for speculators in his Debt-Deflation Theory. Minsky identified the link between debt-financing and asset-price speculation in his Financial Instability Hypothesis. And lower interest makes debt-financing more attractive than raising capital or using retained earnings.

To have continuously low interest and avoid financialisation, I would imagine that one would require laws and a tax regime that overtly discourages asset-price bubbles, excessive leverage etc.

And then there are issues that relate to zero lower bound, the liquidity trap and so on.

I’m not saying you’re wrong (especially not in the short-term) but eventually, those matters need to be addressed.