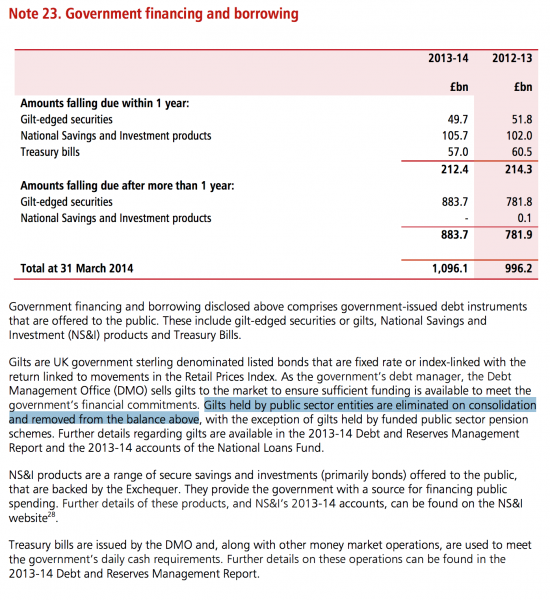

I have, for a very long time, argued that quantitative easing - of all forms - cancels government debt. My argument is simple: it is that if the government owns its own debt then it cannot owe it to someone else and so the debt is, effectively, cancelled. Despite my persistence in arguing this the point has rarely been acknowledged, but is key to People's Quantitative Easing, so I have done a little rummaging in the Whole of Government Accounts for 2013-14 at the suggestion of Neil Wilson. Those accounts show in Note 23 the government's liabilities at 31 March 2014, as follows:

So, excluding National Savings and Investments that is true borrowing of £990 billion.

So, excluding National Savings and Investments that is true borrowing of £990 billion.

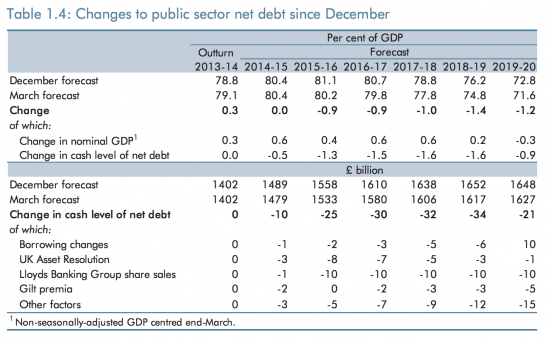

This I have then compared with the figure for government borrowing in the OBR forecasts for the same date in the budget forecasts from March this year:

So there we have debt of £1,402 billion.

So which figure is right? Go back to note 23 in the accounts and the bit I have highlighted in blue. It says:

Gilts held by public sector entities are eliminated on consolidation and removed from the balance above

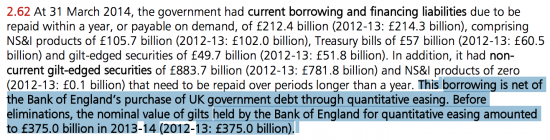

If you want to know what that really means go to page 23 in the accounts:

What that says is that the primary difference between these two figures is the offset of £375 billion in QE which is cancelled in the government's own accounts, as I have always argued. I admit the rest of the difference I cannot explain: maybe the government should.

So I have always been right.

And I am also therefore right to argue that People's QE will create no new government debt. And that no new government interest cost will arise either. As I have also argued.

And what this also says is that all the claims made for the level of government debt in this country are also deliberately and persistently and knowingly mis-stated to feed the austerity narrative. It's about time that was said, loud and clear.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

QE as done to date does allow the BoE to reverse the process (by selling the gilts it owns back to the private sector and burning the cash it receives in return) – so whilst QE does cancel debt, it only does so until it is reversed.

I think the point is that we don’t believe the existing QE will ever be reversed and those gilts owned by the BoE will expire and never be repaid. In which case the QE could have been better implemented by e.g. buying the equity of a grant issuing Green Investment Bank etc, rather than by buying the private sector’s stock of government debt.

But many will not accept this point, and since it’s a belief about the future, their non-acceptance is as unarguable as our belief. And so it’s difficult…

Having just spent the best part of an hour reading your previous two blogs on this topic, and the many – often hostile – comments, I take it that you’re well pleased with the time you must have spent chasing down the figures for this one, Richard. And good on Neil Wilson for suggesting you rummage through this source. To me this removes any doubt about PQE that the naysayers might have – but I dare say that as I type fresh attacks are being prepared. It’ll be interesting to see what line they now take.

Incidentally, I may not be an accountant but I make the difference between the various figures that you mention and the amount you cannot account for £37 billion. Quite a chunk of money. As you say, perhaps someone in the government – i.e. the Treasury – can tell us what it is and where it is?

I feel an FoI coming on….

Thanks Ivan

Quick Richard before they ‘reform’ the FoI act…

I wouldn’t normally comment, being a ‘long term observer’, as it were.

But the question of the ‘missing’ £37B draws my attention immediately

to the £35B that Giddy ‘pulled out of his hat’ at a previous Budget.

You remember – after all the assurances that the BoE and the Treasury most certainly were NOT monetising debt.

They spent the money as if it were revenue as part of that years smoke and mirrors cover up of the enormous state of the Current Account Defecit.

Keep up the good work – the Rest of us non-accountants are very very pleased that you are still here doing the hard sums.

😉

Thanks

Richard and Ivan, if the gap is £37billion (and as I’m looking at this on my iphone, forgive me if this isn’t accurate), this number may be as a result of the assumption of Royal Mails pension liabilities and a differing treatment in public sector finances (OBR) numbers and the treatment under IFRS.

Thanks

A definite possibility

Richard

I’m no accountant either but could the missing £37 billion be interest on government bonds which is/was ‘unusually lodged’ in the BoE Asset purchase facility? Neil Wilson discovered £31 billion there in 2012.

‘The fund in question is the cash account at the Bank of England Asset Purchase Facility Ltd, and on the current cash flow accounts there is £31,324m due to HM Treasury. Yes, you read that right. That’s £31bn sat there doing nothing in an economy with negative GDP growth.

I first drew attention to this account in 2011 when it became clear to me that the Asset Purchase mechanism was slowly unwinding. That is when I discovered that the UK’s version of Quantitative Easing, unlike any other QE system in the world, doesn’t automatically sweep the interest paid on the government bonds back to the Treasury.

The evidence is in the accounts of the asset purchase fund company, where on the Cash flow statement on pp 6 you will see the line:

Due to HM Treasury £31,274m

which is an increase of nearly £20bn over the previous year.’

http://www.3spoken.co.uk/2012/08/the-uk-governments-rainy-day-fund.html

The plot thickens…

If you remember at that time there was a bit of fuss in the right wing press about returning the interest to the Treasury (Jeremy Warner wrote a piece going mad as he smelled a rat that it was back door Treasury funding which of course it did do, and warning inflation coming blah blah,same old story)but if they hadn’t done it that way it would have had 2 Departments with contradictory policies, BoE engaged in QE and the Treasury slowly unwinding it by selling new issues.

As Neil says that we were the only ones doing it that way, the Fed always returned the interest to the US Treasury.

You’ve made a bit of a mistake here.

The government accounts for QE in a consolidated way. Those bonds will appear on the balance sheet of the BOE, but the cash then appears in the government accounts under “Other Financial liabilities” in Note 25.

From pages 116 – 117.

Deposits by banks and other financial institutions included £318.7 billion (2012-13: £297.1 billion) held by the Bank of England and other deposits repayable on demand of £3.0 billion (2012-13: £25.3 billion). The increase since 2009 reflects the fact that the Bank of England Asset Purchase Facility Fund purchased gilts from financial institutions totalling £375 billion as at March 2014 as part of the Bank of England’s policy of quantitative easing.

The QE debt hasn’t totally disappeared from the government’s books. It just sits in a different place in the accounts. It is still counted in financial liabilities.

That’s not a mistake on my part

That’s what QE does

It creates cash

And cash is always a liability on a central bank balance sheet

QE is new money

That is exactly what I have argued

But in the case of People’s QE the government gets to decide how it is spent

The cash as you call it is not on the BOE balance sheet in this case. We are looking at the government’s accounts and as we can see on p116-117 it is sitting as a liability on the government balance sheet.

All that has happened is that the government has chosen to account for QE in a different way. It has not affected the net liability statement.

If this were truly a cancellation of debt, the net liabilities would have decreased by 375bn. In reality this has not happened, and the liabilities have simply moved from the “government financing and borrowing” line to the “other financial liabilities” line.

Cash is a liability of central government!

It has to be if it is an asset of the person holding it

That’s how the double entry of central bank cash creation works

And it has to be a liability – the Bank ‘promises to pay’

BUT as we all know if we ask for cash for or £20 note we are given another in exchange

So this is a liability that does not need to be repaid. It does as a result act like another credit ion the accounts – and that is reserves

This cash is without any doubt still a liability and disproves the notion that QE cancels government debt. In simple terms, the government still owes somebody money. All that has been achieved is shifting it into a different line item.

I assume it was treated as such as on the BOE balance sheet there is an asset of 375bn of bonds and liability of 375bn cash.

So if there has been a zero sum game on the government balance sheet, and a zero sum game on the BOE balance sheet, it is incontrovertible that any debt has been cancelled.

PQE seems to rely on an increase in the asset side of the balance sheet without any corresponding increase in liabilities. Achieved through cancelling debt which as we can see clearly in the governments and BOE’s accounts traditional QE does not do.

Which suggests that either PQE is simply printing money or you have made a mistake in simple balance sheet accounting.

Maybe you can post a blog where you show, perhaps diagrammatically, how PQE works and the effect it has on the government, BOE and third sector balance sheets? I think that would quickly clear up any misunderstandings.

I am sorry: this is quite ridiculous

If you think the government has to repay £5 notes with something other than £5 notes your analysis makes sense

They don’t

And the debt is cancelled: the accounts say so

And yes, to some degree all QE is printing money – which is a job for all governments – it is how PQE is used that matters

I have shown that. There is no need to do so again

Richard and Darius,

The issue of whether currency (notes and coins) should be treated as a liability of the central bank was something raised in comments on another of your blogs a while ago. Under current accounting standards, and national accounting standards (such as the System of National Accounts, European System of Accounts and the IMF Public Sector Debt Statistics Guide and Government Finance Statistics Manual this is certainly the case.

However I’d argue this need not be the case, for the reasons Richard sets out above – the Bank of England, as well as any other central bank issuing fiat currency, is under no obligation to exchange notes and coins for anything else – the part on a UK banknote which says “I promise to pay the bearer on demand” is meaningless.

Treatment as a liability in national accounts and accounting is probably because this was not always the case. Historically, banknotes were convertible, to gold. In national accounting at least, I think notes and coins have remained as liabilities due to convention and inertia, rather than sound economic thinking, but there is a good argument to treat notes and coins like another financial asset – monetary gold. In National Accounts, monetary gold (note – this only includes gold held by monetary authorities, bullion owned by private citizens and gold jewellery is treated as a nonfinancial asset) is treated as a financial asset, but not a liability.

I’d argue fiat currency should not be treated the same way.

Reserves on the other hand are clearly liabilities of the central bank – in extremis, commercial banks could demand the repayment of their reserves in currency, though that’s pretty unlikely.

Its worth noting that the explosion in reserves maintained with the Bank of England shows the failure of QE in the UK to date. As sold to the public, QE was about getting money flowing through the economic veins – the large increase in Bank of England reserves exposes the failure of that policy – we supposedly didn’t want banks hoarding reserves at the Bank of England, we wanted them (supposedly) to lend these funds into the real economy.

To clarify – stupid typos – I’m arguing that notes and coins should be treated in the same way as monetary gold – as a financial asset, and not as a liability of the central bank.

It is apparent from both government and BOE balance sheets and accounts that this debt is not cancelled. If it had been, it would be sitting in the liability column. The form of the liability is immaterial given that with enough cash the government could redeem any outstanding debt.

In short, the government still owes the money you say it no longer does.

Net liabilities in the government accounts have not decreased to the tune of 375bn thanks to QE.

Extending your logic that there are no side effects, surely the government can simply extend this and remove all government debt from its books. It could go further still, which seems to be the basic formulation of your PQE theory.

As I say, it would be helpful if you could post a blog describing the balance sheet effects of PQE, much as the BOE have done for normal QE in their 2014 quarterly bulletin. A step by step guide in such a form would help to clear up any misunderstanding.

If you are not willing to believe what I have already written nothing will persuade you

Non of your articles regarding PQE deal with the question of what happens to the BOE/government balance sheet when the PQE bonds are cancelled. You just state that it is not a problem and there are no consequences.

When looking through other comments on this site on the same subject it seems you just block commentators who fail to agree with your point of view, after you fail to provide answers of any detail. There are serious problems with your PQE idea but your argument consist of “I am right” and everyone who questions must be a neo-liberal, stupid or both.

You seem unwilling to produce a careful and methodical analysis of PQE. As I say, a set of simple balance sheet diagrams would do the trick. As an accountant and economist one would think such an explanation would be well within your capabilities and would remove much of the uncertainty you yourself have created. My feeling is that you won’t subject yourself to this because it shows PQE for what it really is. Helicopter money.

Fortunately, a BOE staffer seems to have written a fairly complete article explaining the differences between QE and helicopter money, complete with asset/liability diagrams.

http://bankunderground.co.uk/2015/08/05/helicopter-money-setting-the-tale-straight/#more-421

I have dealt with what happens when PQE bonds are cancelled, yesterday, in detail

As for the BoE article, it refers to PQE as helicopter money, which it is emphatically not

PQE deletes the newly purchased bonds from figure 2 in the bank underground post I linked to. Leaving the BOE balance sheet looking similar to the balance sheet described in figure 3.

In practice the only difference between PQE and helicopter money is the introduction of the extra step of issuing then repurchasing bonds before cancelling them. It would be simpler to just print the money in the first place.

Certainly the effect on the BOE balance sheet would be the same. The deleterious effects Fergus Cummings describes would also be the same.

You are claiming that PQE can create debt free fiat money. out of thin air as you regularly call it. With no effect on the balance sheet of the BOE, government and no adverse effects.

It carries all the same hallmarks as helicopter money albeit dressed up in a new name and described in a convoluted manner. If it walks like a duck, talks like a duck…..it probably is a duck.

I am sorry – but you a) are wasting my time and b) have not bothered to read a word I have written

I have read through your arguments yesterday. Your argument revolves around step 3, which I will repeat here for clarity of other readers.

Step 3 is where I begin to disagree with the logic. I have long argued that if a government owns its own debt then it is impossible to argue that the debt still exists in any meaningful way. If the public sector produced consolidated accounts (as would be required of a private sector entity) the Bank of England would be considered to be controlled by the government and the debt owing between the Treasury and Bank of England would fall out on consolidation meaning that no third party liability would be reported as owing. In that case to argue that the government has increased its borrowing when in fact this is just an internal financing arrangement is simply factually wrong even if the loan itself is not cancelled.

You argue that debt owed from one government entity to another can be cancelled on consolidation. If this were to be true and lets for argument says it is then the cash generated in the sale of debt between government entities must also be cancelled.

Otherwise accounts and balance sheets will simply not balance. The only other alternative is that new money, helicopter money, has been created. With all it’s inherent drawbacks.

Darius

Respectfully, I am bored by this

I am entirely happy I am right

You are too

Let’s leave it at that

Richard

Richard

Are you evading giving an answer?

ED NOTE:

Repeating your question multiple times contravenes the comments policy of this blog when I have answered it several times already

So, please stop wasting my time and yours by doing so

There are some explicit quotes in those accounts that are nice and I wrote an article last year on the point

http://www.3spoken.co.uk/2014/03/uk-whole-of-government-accounts-some.html

The best one is the last:

“Consolidating Quantitative Easing does not significantly reduce the overall liabilities of government

but it does reduce the number reported as government borrowing. Once intra-government transactions

are eliminated, the scheme represents an exchange of gilts (liabilities of the National Loans Fund) for

central bank reserves (liabilities of the Bank of England).”

@ Neil

Agreed the QE does not reduce overall liabilities, it just shifts them.

Does this then not invalidate the argument that government debt (a form of liability) is cancelled through QE?

Darius

Money is repaid with money

It’s technically a liability but you can’t repay it

What’s the problem with agreeing that?

Richard

If the government spends £100 it will get £100 back in tax eventually if nothing is saved. If there is (net) saving you will get deficits. If banks are lending like mad you could get surpluses even.

The best analogy is bank “borrowing” when you get paid – an involuntary decision to save in the currency. Or do you consider you are “In Credit” with the bank and that is A Good Thing.

Well, we are “In Credit” with the govt.

I admit I have no idea what you are saying

http://www.3spoken.co.uk/2014/04/taxation-government-investment-each.html?m=0

See this article.

I would be a little cautious about how you use these figures, Richard.

There was a change in the way that government accounts were reported in September 2014 ( http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/a0059c2c-a093-11e3-8557-00144feab7de.html ), to accruals accounting perhaps(?), so you may get confusing results if you use reports as at end-FY 2014 and projections from March 2015.

If I may say, I think you should consider Darius K’s comments a little more seriously. I hardly think he is “wasting your time” – I dare say he has written more than you have on this post! When you are getting criticism of your ideas from someone who is sufficiently confident in their argument to explain it in detail, some kind of warning should be sounding in your head.

No warning is sounding at all

The accounting is IFRS compliant and I was right about it

And Darius cannot answer how bank reserves on which interest is due are created by PQE

There is likely to be good reason for that in my view: such reserves are not created

So I a, not getting too worried here