The government has recently released its latest data on the cost of pension tax reliefs. This is something I have taken an interest in before and at that time suggested that there were major issues to be addressed in the private pension system, not least because the pensions it was providing appeared to be wholly funded by the cost of the tax reliefs given. I was, therefore, curious to see how things had changed.

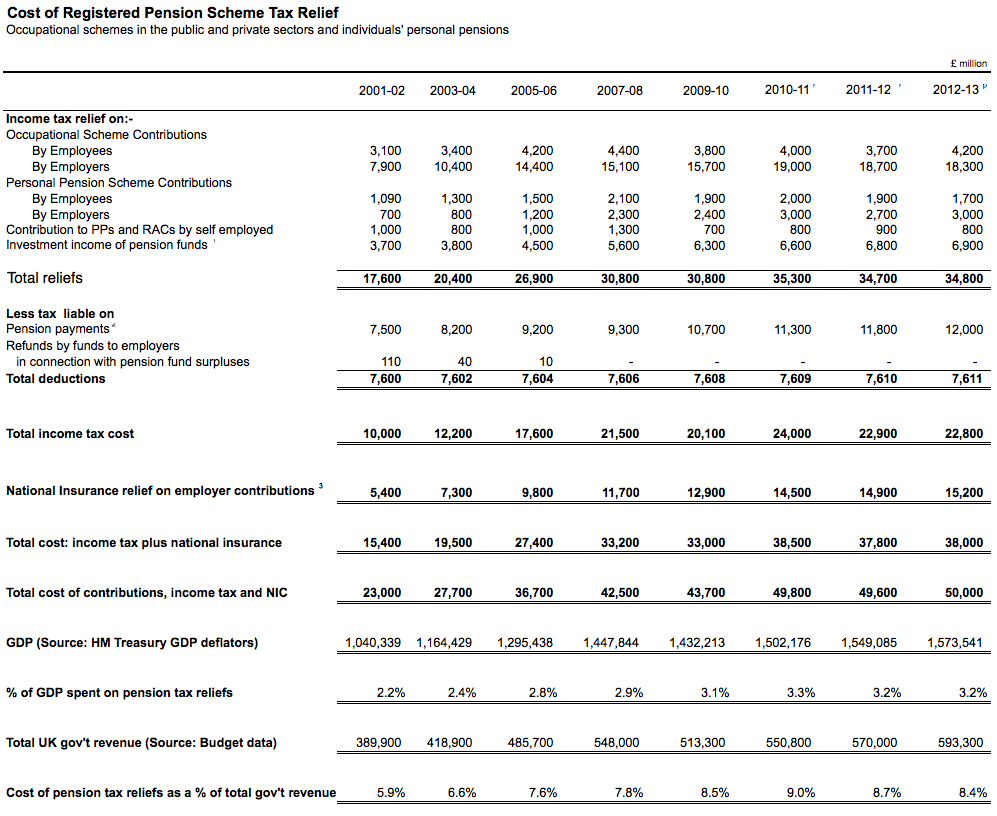

To summarise the recent data I have produced the following table. To make it easier to read I have shown only one year in two at the start of the period.

The data is, candidly, worrying. Firstly, note that the cost of tax relief can be stated in three ways. Then first is the cost of income tax relief: in 2012-13 this was £34.8 billion. Second, there is the cost of national insurance relief on pension contributions. In 2012-13 this amounted to £15.2 billion. In combination these two sums in combination came to exactly £50 billion in all. To offset this, HMRC claim that the tax paid on pensions paid can be offset. It's an interesting claim without any economic justification: the tax paid on pensions paid from past contributions are entirely unrelated to decisions to be made on the tax relief on current contributions, the impact of which will be on future tax revenues. The government is claims these taxes paid reduce the cost of pension tax relief to £38 billion: that is clearly untrue: the real cost of tax reliefs in 2012-13 was £50 billion.

The first thing to note about this cost is that in 2012-13 the deficit was £115 billion. In 2014-15 it is forecast to be £96 billion. (Autumn Statement 2013 data). I'm not sure it need be pointed out that as the cost of pension tax and national insurance relief is steady and the deficit is supposedly falling the fact that these reliefs should exceed 50% of the deficit in 2014-15 is a situation that is likely to persist.

Second, though, what is astonishing is the increase in this cost over time. I have expressed the cost of relief both as a percentage of GDP and total tax revenues, both based on HM Treasury data. As a proportion of GDP the cost of pension tax relief has risen from 2.2% of GDP in 2001 to 3.2% in 2012. As a proportion of tax revenues the increase over the same period has been from 5.9% to 8.4% and peaked at 9%. However it is looked at, this increase is extraordinary.

This is especially the case when it is considered that the number of people in pension schemes is falling quite fast according to the ONS: since 2000 numbers in pension schemes have fallen by about 2 million. Contributions to personal pension funds are also falling.

The decline is not surprising. Firstly employers are abandoning their commitments to their staff whilst, secondly, people have an instinctive feel that pension funds are ripping them off. The lack if transparency in such funds, on which I have written often, does not help, but nor do the facts. As the Royal Society of Arts reported not that long in its report "Building the consensus for a People's Pension in Britain":

A huge proportion of our pensions disappear in fees — with charges swallowing up to 40 percent of the value of the pension.

If a typical Dutch and a typical British person save the same amount for their pension, the Dutch person can expect a 50 percent higher income in retirement.

That minor changes to our regulatory framework could boost pension returns by 39 percent.

To put it another way, what that suggests is that something close to, and in many cases more than, the amount of tax relief given on pension fund contributions is taken by the pensions industry for the benefit of the City and the financial services industry without a penny of benefit going to potential pensioners. No wonder then that so many people get to retirement age and suddenly realise that their pension fund is now worth little more than they invested in it despite pension tax relief and that their future is not quite as bright as they hoped if might be.

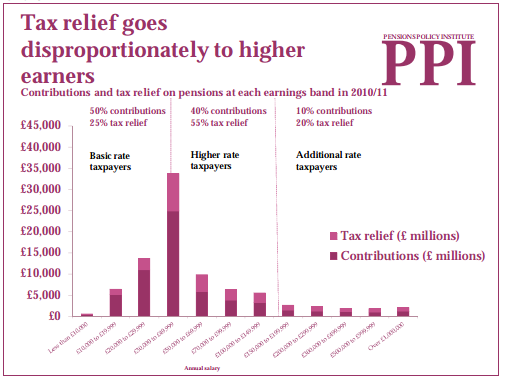

So what should be done about this given that there is also strong evidence that a substantial part of all pension tax reliefs go to those on higher levels of income (as is inevitable: they have the capacity to save and pension tax relief is, at the end of the day, simply a subsidy to savers) as this table from the Pension Policy Institute shows:

As this chart makes clear, 20% of all pension tax reliefs go to the top 1% of income taxpayers, or just over 300,000 people. That is a a cost of almost £16,000 each.

55% of all tax relief based on this data goes to higher rate taxpayers. That is about £27.5 billion to about 2.7 million people, at a cost of almost £10,000 each (rather surprisingly). The balance of just £12.5 billion is split between about 27 million people, in principle, although many, of course, will get none. That is about £460 each. In other words, actually to the richest in society on their pension contributions is worth almost 35 times the amount that it is worth to 90% of the UK population.

In the light of this what follows is not a suggestion I suspect anyone will follow up right now, but it is a serious proposal, nonetheless. I suggest the abolition of all current pension tax reliefs. I mean that: I would suggest abolishing the lot.

I suggest as a result that the whole £50 billion of spending on pension tax relief be put back into the government spending pot.

My primary reason for doing this is that existing pension tax relief is fundamentally unfair in its distribution for the reasons noted above: it is absurd that this relief is so biased towards the wealthy who have least need for it precisely because they are already wealthy.

My second reason for this suggestion is that if this relief was abolished then the total spending on state pensions, which is at present about 42% of all social security spending according to IFS data, or about £92bn this year based on the 2013 budget, could be increased substantially. I find it at least at least a little offensive that we can in this country at this time spend £10 billion a year subsidising the savings of the richest 1% in this country who are still in work whilst only spending a little over £90 billion on old-age pensions. I would much rather that old age pensioners had a 10% pension increase than this relief went to the richest 1%. And, if you want a massive redistribution of well being in this country for the benefit of everyone it is hard to imagine anything that could be more effective.

Such a policy makes complete macroeconomic sense, as does using part of the balance of savings from ending this relief to close the deficit to avoid other stresses we face. This would have the additional benefit of limiting the impact of the boom and bust cycle that the stock market generates, part of which is fuelled by the incessant flow of pension fund contributions into that market when they have no other useful place to go.

But what then of pension funds? What do I suggest should become of them? Existing funds would, of course, persist, and so would the pensions they pay. And so too, incidentally, would the tax payable upon those pensions persist as well for a long time to come, which is why the Revenue are wrong to offset these tax revenues against the cost of tax reliefs.

This does not, however, deal with the question of what would replace pension funds. Such a replacement is necessary because I am not suggesting people should not save for retirement; that would be absurd. Many people have looked at this question. I have no right or wrong answer, but I do have a simple one which reflects the reality of what people are actually doing.

The fact is that as people leave pension funds they appear to be saving for their pensions in two ways. The first is through ISAs. They are doing this for several reasons. First, because for most people the ISA limit is more than they wish to save a year, anyway. Secondly, they know that in an ISA they have more choice on how funds are invested. Thirdly, they recognise they get some tax relief from this, but as importantly, no tax consequence when they take the money out, which they like. Fourthly, many realise that the pension rules were designed for an old patrician economy where jobs for life were a reality and economic shocks did not happen. But now they do: the flexibility of ISAs allows for that fact.

And other people save for pensions through buy to let arrangements. The number of people who have confidence that traditional finance markets will provide for them is falling and with good reason: big business is sitting on a pile of cash it has no clue what to do with. Why in that case should pensioners trust big business leaders to provide for their futures? They want so something they can comprehend and right now what they understand is that when their pension fund puts money into companies like Barclays that cash is being taken for a ride by the management who put the interest of their shareholders second.

So new pension funds need to be built around three things. The first is a tax free savings environment but where tax relief on capital into the fund and and tax on payments out need not apply. This would massively simplify pension arrangements. The ISA model works.

Second, people want certainty and pensions do not give it. I have long argued that infrastructure and employment generating bonds provide such certainty. I still think if people could invest in their local communities they would, and likewise if they could invest in the NHS - which they know they will need in their old age - they definitely would. The rates of return paid could be a lot lower than PFI and still provide a fortune in savings for public sector infrastructure costs and a fair return to pensioners.

Third people want to invest in housing and we need a lot of it: social housing funds could be the basis for pension arrangements for a long time to come and provide enormous social worth to the UK.

And how could this be incentivised? I would not be averse to the government providing bonus returns to long term holders on such funds as a pension incentive. I suspects this could easily be engineered within EU competition law.

As for the pensions to eventually be provided, annuities would survive, but as many know, they're hardly attractive at present. And the reality is that as new style savings funds would not get tax relief on contributions on the way in ( but charges would be very low so that the amount actually invested out of contributions made might well be higher than at present) then there would also be no tax on the way out either. I agree: this does not provide a basis for a guaranteed income for life but I strongly suspect an insurance based product for those of retirement age could be designed around this scenario without much difficulty. If not the financial services industry is of little use to us.

So, why do this radical reform? I suggests there are at least five reasons.

First to boost pensions for all, as could be done by using come of the funds saved to significantly increase state pension provision.

Second to redistribute the currently wholly inequitable spending of almost 9% of total government tax revenue on largely subsidising the savings of the well off.

Thirdly, to give the economy a current boost as a result of the redistribution that will arise from this.

Fourthly, to end the state subsidy of a part of the City that has grown fat on capturing state largesse for its own ends.

And lastly, to provide a savings mechanism that meets 21st century demand and need as evidenced in the reality of what people are actually doing.

Will this happen? I doubt it, very much.

Should it happen? Yes, I think it should and I very strongly suspect many of us would be very much better off as a result, including all those about to be enrolled in new state sponsored pension arrangements that will all be 'invested' in conventional stock market based portfolios and no doubt will be lost for future generations of pensioners in this country as a result. Such arrangements belong to the past and simply fatten the City at cost to the rest of the economy.

It's time to deliver new pension savings mechanisms, capable of being run collectively but with individual identifiable funds and transparency and easily made investment choices that ordinary are people are capable of making and understanding that provide the flexibility they need for the lives they now lead. Existing pension arrangements are far from that.

No doubt there will be howls of protest at this suggestion but let's face it, the pension industry is a heavily state subsidised, seriously inefficient industry that is failing to meet consumer need. Hasn't that always signalled a need for major reform? Why would markets want to object to this one?

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

I struggle to disagree with the assertion that the pension industry is in a mess

and does not serve its investors well. I also agree that tax relief has ended up being a bung for the industry.

Choose a pension

Choose absolute return, multi-asset, a fund of hedge funds and 5% bid offer spread.

Choose from 1500 funds, none of which you have a clue as to how they work.

Choose lifestyle, drawdown or inflation linked annuities with matching whole of life cover.

Choose procrastination induced by choices you don’t understand.

Choose an ill informed I.F.A. for 120 quid an hour and wonder who the pensions industry is set up to serve.

Choose mind numbing, all inclusive disclaimers to read and sign.

Choose your capital being slowly eaten away by commission, administration, dealing and management fees.

Choose a history of scandals, mis-selling and an industry hiding behind a raft of

opaque jargon and poorly understood legislation.

Choose a pension.

Appologies to Mr Welsh.

http://ruraldebugging.blogspot.co.uk/2013/06/recycle-waleshome-pension-article.html

https://blogs.oracle.com/clive/entry/hitchhikers_blog_posting_to_pension

I think your suggestion of bunging all the savings from abolishing tax relief at the state pension needs a bit more thinking about.

The problem is that, as things stand, any increase could be swallowed up by resultant drops in means-tested benefits for the worst off pensioners, meaning you’ll have replaced one bung to the rich with another one.

You could possibly transfer the money wholly to the Pension Credit scheme. including the savings credit, which would mean a better targeting whilst ensuring that those with private provision also have a stake but any means tested benefit faces issues with take-up.

On a more general point, I had no idea the numbers in tax relief were so huge. Another way of looking at it is about half the social security budget for those of working age which we’re constantly told is ‘unsustainable’. Cuts to these payments are always presented unavoidable austerity, whereas any threat to pension contribution tax relief is a ‘raid on pensions’.

Note I dis not suggest bunging it all at existing pensions: I think some could be

The scale is staggering: that’s what I’m really highlighting

According to polls-most of the Tory vote is from the 60+ age group-no surprise, then!

I do agree with you Richard, that most working people’s pension provision can be catered for using the ISA structure and the annual limits could be increased if necessary in future. The pensioner then has complete freedom to take lump sums or buy a personal annuity/ies at any age he/she chooses.

These personal annuities would have a calculated “capital content factor” so would attract less income tax, but in view of the lack of original tax relief, it would be reasonable to make these personal annuities free of basic rate tax and pensioners would have the means of providing self-sufficiency in old age.

Yes, the scale of tax relief for “pensions” is a colossal figure, it is ball park as much as basic state pensions in payments (excl. SSP).

It doesn’t even benefit savers, the insurance companies cream off half of it in higher charges and the other half merely pushes up share prices (i.e. whatever the funds invest in).

But you’ll not make yourself popular by suggesting we phase it out 🙂

I wasn’t courting popularity!

Would your plan also apply to public sector final salary pensions?

Tax relief is not an issue there….so beyond it

How is tax relied not an issue??

Are you honestly claiming that employee contributions to public sector final salary schemes are not treated consistently with other pension contributions (and therefore are not currently lower than they would otherwise need to be to fund the appropriate benefit received)..??

That’s a bold claim but one not supported by evidence, unless you can provide something to the contrary…

It really is time you realised that the government is not the same as the ret of the economy

It does not, for a start, get tax relief on its contributions

Tautologically, it cannot