Arthur Laffer's “curve” is one of the most destructive ideas in modern economics.

Sketched on a napkin in the 1970s, it claimed that cutting tax rates could increase government revenue.

It became gospel for Reagan, Thatcher and every neoliberal government since.

But it was wrong.

In this video, I explain why Laffer misunderstood tax, ignored inequality, and helped unleash tax competition that undermined democracy.

I debated Laffer in person — and I'll show you why his logic collapses when tested against modern money and real economies and the idea that fair taxation builds strong societies, whilst low taxation builds fragile ones.

This is the audio version:

This is the transcript:

Arthur Laffer is one of the bogeymen of tax.

Whenever there's a discussion about tax rates, his name comes up, and that's because his idea, called the Laffer Curve, has shaped 40 years of neoliberal tax policy. But there's just one thing wrong with this so-called Laffer Curve, and that is that it is wrong.

Arthur Laffer didn't understand tax. He didn't understand why tax rates are set, and he came up with answers that were deeply destructive with regard to wealth distribution, but which also led directly to tax competition, which undermined states, markets, and democracy. So let's unpack what Arthur Laffer had to say and why it's so dangerous.

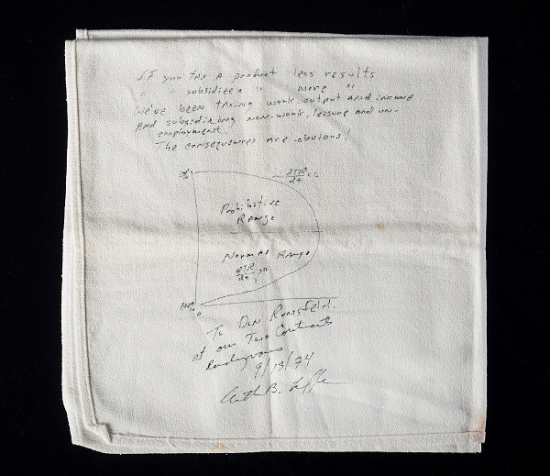

In the mid-1970s, Laffer sketched a simple curve on a napkin. He did so whilst having dinner with two people. One was Donald Rumsfeld, who later became the US Secretary of Defence. And the other was Dick Cheney, who later became Vice President and served no less than four US presidents and died very recently.

It showed tax revenue on one axis and tax rates on the other. He drew them in a slightly odd way in his original diagram, and we'll switch them around in the course of this presentation. But the point is that what he claimed was that at 0% tax, a government raises no money. And at 100% tax, he said, people stop working, so revenue is also nothing, which, by the way, isn't exactly true because that's what happens in communist states, and therefore, people do carry on working with 100% tax, but let's not go there because we don't want a communist state.

Somewhere in between, he argued, there lay an optimal tax rate that maximises revenue, in his opinion.

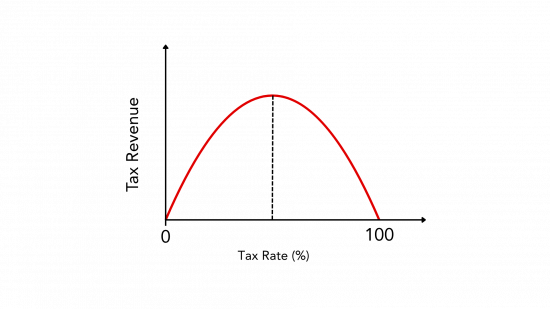

The diagram that Arthur drew, when translated into a more easily seen format, looked like this. We've got government revenue going up the Y-axis, that's the vertical. And we've got the tax rate going along the horizontal axis, that's the X-axis. And the tax rate runs from 0% to 100%, and in Arthur's worldview, there was this nice, even curve. If tax rates were below the optimal rate, which is the dashed line, then you could increase tax rates and get more revenue. And if taxes were above the optimal tax rate, you had to cut taxes because you would actually raise more money as a consequence of cutting them. That was what he said.

Laffer's logic was simple. Higher taxes, he said, discourage work and enterprise, and beyond the optimal tax rate, people avoid taxes, evade taxes, or simply stop working altogether. That's what Arthur claimed. And he therefore suggested that lower tax rates might actually increase total revenue, although he could provide no examples to prove that this was true.

Despite that, this claim underpinned both Reaganomics and Thatcherism. And it is now the economics that underpins the policies of Reform, the Tories and even Labour in the UK, all of whom still seem to believe that low tax rates will, somehow or other, without any evidence to support the claim, deliver an economic nirvana. But there was, as I've already said, never any evidence to support the claim.

In 2017, I debated this issue with Arthur at the OECD. We met in person. We had a couple of meals together. We got on terribly affably until the debate was over. And what we were asked to discuss was exactly what I'm talking about in this video. And there was a voting audience for the debate that we had. Over 300 people voted from an American business organisation who sponsored the event; inherently right-wing, as a consequence, with a bias built in. And I won, I beat Arthur by 58% to 31% with the rest being undecided.

The point is quite simple, that I know what I'm talking about here because Arthur and I have discussed this face-to-face and behind podiums. And the point I made then and which I repeat now, is that the data shows there is no revenue-maximising tax rate in most economies.

The curve ignores inequality.

Tax avoidance is not motivated by the desire to bring the rate down to an optimal level, but simply because people don't want to pay.

And it ignores real-world behaviour, which doesn't give many people the option to actually opt out of work once they've started. If you are at work, you can't say after 27 hours, "Now my effective tax rate is too high, and therefore I'm going to do no more hours this week." When you're contracted to do 37.5, you are going to do the 37.5 whether you like it or not.

And anyway, Scandinavian countries disprove Arthur's claim. High taxes have been equated with strong growth. Look right across Europe, and look at the countries which are seeing much higher rates of productivity than the UK and much higher rates of growth, and they've got higher taxes too. In other words, most people don't stop working when taxed more. The theory confuses economic incentives, if Arthur ever got those right, with social reality.

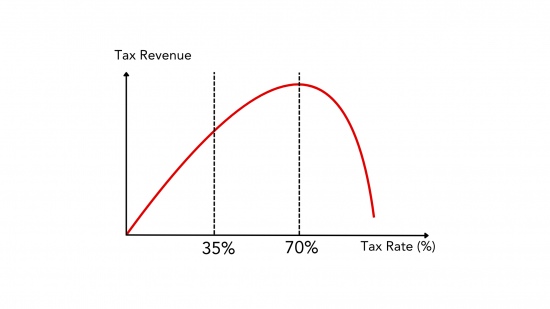

More than that, though, even those who can choose to link their work effort to the tax rate provide evidence that they will actually still carry on working at current tax rates. The actual evidence from academic research is that the tipping point rate inside most economies is around 70% overall tax rate. But in most economies, like the UK, the actual effective tax rate is between 35% and 40%. So, we are so far away from the tipping point tax rate that cutting taxes will always guarantee that the government will get less tax revenue.

This doesn't mean to say that there isn't a point where the reverse could be true. But in practice, no one is anywhere near that situation literally, almost anywhere in the world, so we don't need to worry about it. And there is no such marginal tax rate in the UK except for some people on very, very low earnings when they come off benefits and go into work. Those people should have their situation corrected. For everybody else, the Laffer Curve does not apply; Arthur taught nonsense.

And he taught nonsense for another very particular reason, which is very rarely discussed. In the 1970s, when Laffer first drew his curve on the back of that napkin, he thought that taxes funded the government. And in the early 1970s, he wasn't necessarily wrong, because the USA had only just come off the gold and the consequences of that with regard to government funding simply were not understood at the time, let's be clear about it: modern monetary theory (MMT) was not known.

But now we know that taxes don't fund the government; government money creation funds the government. And tax plays an entirely different role in the economy now that we have what are called fiat currencies; currencies that only have value because the government makes them legal tender. And in that situation, tax is used to recover from the economy the money that the government has spent into existence through its spending programmes. In other words, the dynamic around tax has changed totally since Arthur Laffer first thought of his curve.

We now know that there is a twofold purpose to tax: one, reclaiming money, and secondly, to enforce a social agenda that is imposed via the taxation system, whether that be with regard to tackling inequality or to dealing with mispricing within the marketplace, or to simply promote certain chosen activities that the government wants to be undertaken.

And all of that makes a mockery of what Laffer said, because if tax is not paid out of private sector money - the euphemistic taxpayers' money that politicians always talk about, but which doesn't actually exist, because all the money that is used to pay tax was created by the government in the first place - then this idea that the capacity to pay has a direct impact on the willingness to work doesn't hold. The tax issue is not, as Laffer said. Governments don't now try to maximise revenue; instead, they seek to control inflation by taxing. And therefore, the relationships are fundamentally different now.

So this is why there is a fundamental flaw in everything that Arthur Laffer had to say. But despite that, what he did create, the so-called Laffer Curve, has become political dogma. And it's rolled out time and time and time again by our right-wing think tanks in particular, but also by Conservative politicians and others from Reform, and even from Labour. And it has served the interests of those who want lower tax on wealth and capital very well, which is why so much money has been paid to promote this falsehood within our economy.

It has effectively become a slogan for those who want to cut the size of the state. They say they want to cut taxes to grow the economy; actually, they want to cut taxes to reduce the size of the state so that others lose out, and they think they get wealthier. This is all about an idea promoted to increase inequality.

And that is seen in the other dimension of the consequence of this curve, because it has been used to promote the idea of tax competition as well. Tax competition still exists, and it's something that I have worked against for a very long time. The Tax Justice Network, which I was the co-creator of with John Christensen in 2003, existed to fight tax competition because tax competition exists to cut corporate tax rates in particular, but also to attract the mobile capital of the wealthy. And it basically did this by promoting a race to the bottom with regard to tax rates on companies and wealth.

The result was obvious. Multinational companies shifted their profits on paper to low-tax havens, and the wealthy hid their money in those same places. That was what Arthur Laffer thought was the right outcome for society. And I know, because again, I repeat, I've debated this with him.

Laffer believed, when saying that low tax rates were good for firms, that the government was like a firm. In other words, his logic was that the state could fail and be replaced if it wasn't efficient. And he claimed that low taxes equalled an efficient state. But that's ridiculous because a company can fail and be replaced, so long as it's small enough, but a state that fails leaves chaos. There are only a few real failed states in the world, and just look at the consequences in Sudan and other such places.

The state cannot fail, but the whole point of Laffer's tax competition was to deny revenues to the government, so there was a collapse in services and a resulting democratic decay.

Tax isn't the price we pay for government; it's the foundation of a currency. But if you undermine tax, what you do is undermine the capacity of the state to govern and all that it does. That means that tax competition is a direct assault on democracy itself, in the process transferring power to global corporations.

The consequence is that tax competition has distorted markets, rewarded tax avoidance, and it has denied necessary innovation because money has been spent on financial engineering and not real engineering. It increases inequality and shifts the burden of tax onto ordinary workers. And Laffer and the Republicans were, of course, entirely indifferent to that, as we can still see in the behaviour of Donald Trump today. But worse still, this competition has reduced fiscal stability, leaving some governments weaker in crises.

The answer is that we don't need to adopt any of the thinking of the Laffer Curve. What the evidence now shows is that countries with fair, progressive tax systems are almost invariably more stable than those with low tax systems. And it is cooperation and not competition that supports healthy markets, and lower taxes do not guarantee growth. In fact, chronic under-taxation only breeds mistrust and disillusionment.

The Laffer idea collapses when tested against real-world economies. So we must end the global race to the bottom in tax. We must use the tools that are available to assess the risks from it, and that includes the tax spillover assessments that I have created with Professor Andrew Baker at Sheffield University, because that's exactly what they were created to appraise. And we must enforce tax transparency and data exchange from tax havens because these are essential tools to challenge this whole idea of tax competition, and I was pretty pivotal in the creation of some of those ideas.

The consequence is that we need to restore fiscal sovereignty and democratic control. We must tax wealth and profits and carbon fairly, and we must ensure that those who have little are not taxed a lot.

Laffer's napkin became a global myth. It promised prosperity, but it delivered inequality.

Fair taxation builds strong societies, low taxation builds fragile ones.

The Laffer Curve was wrong, and it's time to stop letting that myth guide our future when the reality is that low tax on the wealthy and large companies are helping destroy our well-being.

Poll

Comments

When commenting, please take note of this blog's comment policy, which is available here. Contravening this policy will result in comments being deleted before or after initial publication at the editor's sole discretion and without explanation being required or offered.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

There are links to this blog's glossary in the above post that explain technical terms used in it. Follow them for more explanations.

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

Buy me a coffee!

Buy me a coffee!

“Five Critiques of Arthur Laffer’s Supply-Side Model Show Tax Cuts as Junk Economics”, Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy

https://itep.org/debunkinglaffer/

Why the Laffer Curve is garbage, Josh Elliott, CT Mirror

https://ctmirror.org/2018/01/18/why-the-laffer-curve-is-garbage/

Resist the Allure of Laffer Curve Logic, Adam N. Michel, CATO Institute

https://www.cato.org/blog/resist-allure-laffer-curve-logic

And yet his economic thoughts still seems to have currency as witnessed by a double page spread in the Times newspaper 17.10.2025 ‘This plan could get Britain back on the path to prosperity’ Unfortunately I can’t quote from the article now as it’s behind a paywall but I do remember a couple of his proposals were a flat tax system and big cuts in public spending.

Agreed

That may be why this video is getting a loot of veows – way above average.

Thanks to you and your team for an illuminating article.

Might it be that an “economics”/“sneakonomics” theory has its power, not from its validity but from its being widely and persistenly “marketed”?

Might it be that any “economics” theory/imposition is, at best, seriously questionable when it does not include (likely) social consequences?

Might Mr. Laffer’s Curve be reasonably classified as “Courtier Economics” ?

Yes, in a word

It IS a very dangerous idea. It starts with a fundamental truth but quickly takes on an agenda…..

The truth is that if tax rates are zero then there is zero revenue and at 100% people will either avoid it or stop work… meaning zero revenue. It is also reasonable to assume a continuous function of “rate v revenue” which does imply there is a rate where revenue is maximised….. this is simple maths. But from here on it descends into nonsense.

First, that taxation is all about revenue maximization. You have already written much on why tax is so much more than revenue generation.

Second, it says nothing about where that “maximum” actually is. We just don’t know…. (partly because in recent times we have never had rates high enough to find out where it is).

Third, it legitimises all the “well, the rich will all move to Dubai” scare stories…. which we know, in general, are not true.

Fourth, when stated it might have been an academic curiosity…. but 50 years later we can see the destruction it has wrought.

Time to put this idea out of its misery.

Much to agree with

Sometimes you want people to stop work.

My other half always uses the example of Bruce Forsyth, who got to be so popular and desirable as a presenter on live and tv shows, that he effectively became a monopoly.

By imposing 99% as the marginal rate of tax, it became not worth his while to take on yet another gig.

Which left room for up and comers like Jimmy Tarbuck. Who would have had to wait for ‘dead man’s shoes’ otherwise.

Tax is always about shaping the society you want.

It seems there are always good explanations as to why the rich should be allowed to get richer and why the poorer should contribute their share.

I remember in the Thatcher era there were always arguments that paying nurses too much would attract the wrong sort person,whilst at the same time saying we had to pay bankers and senior managers a good salary to attract talent.

I am much more of a view that tax including Council Tax should be minimal for those on low incomes and the richer should contribute much more. Also that unearned income should be fairly taxed.

I can understand why Laffer did not like you logically arguing why his curve was wrong!

Very much so. We see examples in the UK in recent years where higher taxes on tobacco have led to a reduction in government tax receipts. And it’s been appalling in Australia where receipts are through the floor, mini-marts get firebombed, and the black market accounts for over half of sales. This is not due to the Laffer curve as the economists tell us but due to behavioural change.

I hardly think you are the best person to discuss the incentive to work through higher or lower taxes given you have relied on charitable donations for the past 20 years. Go and “walk around” and ask those on a building site or digging up roads and ask them what they think.

How very odd. Apart from the fact that I was in full and part-time employment by universities for nearly a decade in the period to which you refer, and that I now, in fact, run a business that does not rely on charity, when I did receive grants they were never donations but were payment for work to be undertaken. If you so little understand what I am about how on earth do you think you have the right to offer advice?

If Richard did walk around he’d find a lot of working people now incapable of working out who it is that is screwing them, James Foster and too eager to accuse anyone but the real source.

Robert Draper, an American historian wrote ‘To Start a War’ How the Bush Administration took America to War.’

Draper interviewed a lot of people and not just those at the top. He concluded that Cheney and Rumsfeld manipulated the decision process by restricting those who might give the ‘wrong advice.’ Bush did not, as Churchill, Clinton and Obama, assemble the various diplomatic, intelligence and military leaders in one place. Bush was the wrong leader for the time.

Rumsfeld tore up the plan, based on the experience of Germany and Japan in 1945, for the occupation of Iraq. The result was chaos and inter- communal fighting.

In my opinion those two men are war criminals.

Another excellent post. 🙂

“Do you think lower taxes make a country richer?”, is an interesting question.

If you reduce taxes on the wealthy that directly increases inequality. Furthermore the budget deficit increases. This shouldn’t, in itself, matter but, with the current misguided policy choice of “The full funding rule”, this increases government borrowing and interest rates. That, in turn, funnels more money to those putting their money on deposit with the government by buying gilts. So with the current policy choices, cutting taxes gives money to those who already have it, i.e. the wealthy, and thereby further increases inequality.

Reducing taxes on the wealthy, if the government insists on “the Full Funding rule” is not sustainable. The government has to borrow more and more. Interest paid on deposits (gilts) means the rate of borrowing has to increase. Cuts to government services ensue. Eventually democratic society collapses. This is what right wing pundits warn us is happening now and they use it as justification for ever more extreme government cuts (but never tax rises on the wealthy).

The solution is obvious. First ditch the full funding rule. Borrow, at zero interest, from the Bank of England if need be (actually money creation). Secondly, repay deposits, buy back gilts, QE, (using more money from the BoE). This both reduces government spending interest rates. Thirdly, tax the wealthy.

However, if you reduce taxes on the poor (or increase benefits) something a bit different happens. Unlike the wealthy, who mostly save any tax reductions, the poor spend almost all their gains. This then becomes other people’s income and produces a multiplier effect. Now the question is, even with the absurd full funding rule, does the economy grows more quickly than the additional borrowing? If so the country becomes richer and the process is sustainable (though the full funding rules should still be ditched).

To me, whether lower taxes make the country richer depends who benefits. If they are tax cuts for the wealthy they make the country poorer. But if they are tax cuts for the poor then the country might, just, become richer (though it would be much better if we ditched the full funding rule). That’s the opposite to the logic of the Laffer curve.

Neoliberal “competition” is like holding a series of races where the winner of the first race gets a three yard start for the next round, second gets a two yard start and third gets a one yard start. Repeat for the “competition” of ten races. How far ahead will the winner of the final race be?

🙂

I cant get it to play at the moment but the Laffer Curve is on the board in this clip from Ferris Buellers day off.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AyyAh2lQXF8

Probably one of the worst films ever made

How appropriate…………..

Perhaps it should be renamed the Having A Laffer Curve.

For me, this is what you get with over-mathemati-cised economics – sanitized outcomes devoid of ‘political economy’ and seemingly ‘neutral’. But always in favour of wealth of course.

Perhaps the clue was in the proponents name ‘ ‘Laffer’ – as in 2008 there was an embezzler called Bernie ‘Madoff’.

Maybe Arthur’s real name is spelled ‘Laugher’ because he was taking the piss anyway but managed to get away with it?

Kathleen Tyson reposted Nov 9

@shanaka86

(Slightly edited for brevity)

“MONEY SUPPLY JUST BROKE THE SOUND BARRIER: 121% OF GDP AND RISING

The United States now holds more money than it produces. Broad money supply sits at 121% of GDP. For the first time in modern history, the stock of dollars exceeds the annual flow of everything America makes, builds, and sells.

This is not an accounting error. It’s monetary physics breaking down in real time.

The mechanism is brutally simple.

Banks create deposits when they lend. Those deposits become money supply. When people hoard cash in savings accounts, money market funds, and Treasury bills instead of spending it, velocity collapses below 1.0. The money exists but it does not circulate. It accumulates in the top decile while Main Street wages stagnate.

Interest rates turbocharge the problem. When the Fed pays 5% on reserves and T-bills yield similar rates, wealthy holders get paid to NOT spend. Asset prices explode. Housing becomes unaffordable. Equities hit record highs. Grocery bills compound. The velocity gap turns into a class weapon.

The danger is not what you think.

Hyperinflation does not come from high money supply with low velocity. It comes when velocity suddenly reverses. When credit accelerates. When fiscal stimulus hits. When rate cuts unlock hoarded trillions.

That is when supply chains cannot match demand. That is when price controls fail. That is when currencies collapse.

When velocity inflects upward while supply remains constrained, consumer price inflation will catch up with asset inflation within quarters, not years.

This is not conspiracy. This is plumbing.

The money supply exceeding GDP is not fake prosperity or magic. It is balance sheet mathematics combined with incentive structures that reward hoarding over circulation. The Federal Reserve, Treasury, and banking system created this regime through quantitative easing, interest on reserves, and collateral rules that privilege financial assets.

The consequences are measurable. Wealth inequality at Gilded Age levels. Housing affordability at historic lows. Real wages stagnant for decades while stock portfolios double.

The system works exactly as designed. The question is for whom.”

That last sentence says it all.

Hmmmm…..sort of

The curve presumably only applies to earned income. And as discussed the general shape appears to be wrong.

Aside from that it ignores that people are more likely to have an hourly net income they’re willing to work for rather than a percentage lost. With progressive taxation, the hourly rate may still be very favourable. Given a choice between work with a 0% tax rate at £15/hour or work at £100/hour with a 50% tax rate, the latter is clearly far more advantageous.

If you had a very high earner rate of 75% for salaries above, say, £250k, that’s still approx. £130/hour gross, and £32.55/hour net. Someone earning that much might conclude it’s not making much of a difference to work more at that point, but they’re still getting >2.5x as much as many are working for.

If they feel disincentivised, then it leaves high-skilled work available to others.

If the efficiencies of AI changes mean instead of a concentration of wealth we instead move towards a 4 (or even 3) day working week with remaining work and their rewards remaining more evenly distributed, then that will be a successful societal change.

Interesting Curve Man on BBC Radio 4 lunchtime news today; unchallenged by anyone and with subtle put down on accountants compared to economists who know what they’re talking about. You’re obviously touching a few sore spots.

I may catch up later.

Oh no, Laffer has just been interviewed on R4 World at One! (11 Nov) I will have to resort to ‘Listen Again’ to take it all in. Richard, I think we all need to send out the transcript of your post above before he gets any more air time before or post budget!

Richard,

Your inversion of the orthodox story, that the state spends money into existence and tax mainly withdraws it, is a useful corrective to household analogies. But it pushes too far, and in doing so it underestimates what is still valuable in the Laffer intuition.

The modest, defensible core of the Laffer Curve is not the political slogan that tax cuts pay for themselves. It is simply that tax policy operates on responsive agents. At some point, higher rates provoke changes in work, reporting and location that reduce the revenue you hoped to raise. That is a reminder that the state does not act on inert material.

Your account, by contrast, abstracts from the way fiscal authority is actually exercised. In the UK the Treasury really does tax and borrow to finance expenditure. If ministers must in practice secure revenue, then a tool that shows where revenue begins to fall is not a myth, it is a planning aid.

There is also a question of timing. You make tax do the work of restraining inflation after spending has occurred. Yet inflation, and indeed avoidance behaviour, can move faster than tax legislation. The Laffer perspective, by highlighting diminishing returns at higher rates, cautions against assuming that a later tax adjustment will neatly drain away excess demand.

In an open economy the point is sharper. Mobile income and profit are precisely what move when rates climb. That is the very circumstance Laffer was trying to describe, a point where the base erodes faster than the rate rises.

Finally, there is a political virtue in keeping spending tied, at least conceptually, to revenue raising capacity. It disciplines governments to justify their calls on society’s resources. Your framing risks loosening that connection. Laffer, properly understood, keeps before us the thought that beyond some point, more tax yields less of what government needs to remain credible.

Thank you for your comment.

I agree that the Laffer Curve has a modest, defensible core: of course people respond to incentives, and of course excessive rates can distort behaviour, bit almost none exist. Where I differ is in seeing that insight as a constraint on political imagination rather than as a guide to good economics.

First, the fact that taxpayers respond does not make the state a household. When the government spends, it injects money; when it taxes, it withdraws it. That is a matter of monetary mechanics, not metaphor. The Treasury’s operational routine of “tax and borrow to spend” is an artefact of self-imposed accounting rules, not an economic necessity. The sequence can be properly reversed without changing the real constraints — which are always the availability of people, skills and resources, not the balance on a spreadsheet.

Second, the Laffer intuition is often used to suggest that public purpose must yield to private threat: that if the wealthy move, the state must back down. I would invert that. A just tax system should be designed to prevent mobility being used as blackmail. If income or profits can shift across borders too easily, that is a case for reform of corporate, capital-gain and residence rules, not for cutting rates. The erosion of the tax base is a policy failure, not a natural law.

Third, on timing and inflation, you are right that fiscal responses must be agile. But inflation does not arise simply from excess spending; it stems from shortages, profiteering and supply bottlenecks. Address those, and tax becomes a fine-tuning tool rather than a brake on government action.

Finally, I do not want to sever the link between tax and accountability. Quite the opposite. Tax gives value to money, expresses our social contract and sets limits on private power. But it should never be a precondition for care, justice or ecological repair. Governments remain credible when they meet real needs and explain how tax sustains the monetary system that makes that possible — not when they chase an imagined point on a curve drawn in 1974.

The Laffer Curve may describe behaviour at the very margins, but it does not in any way define the limits of a democratic economy.