The price we pay for the failure of the Bank of England is very high.

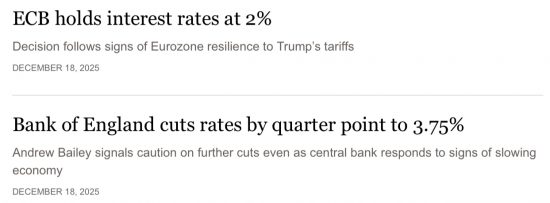

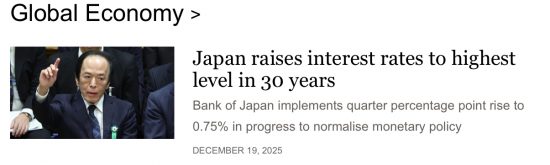

These are three headlines from the FT this morning:

Right now, I am not analysing. I am just noting.

Of course, we are doing badly with interest rates as high as those we suffer.

And four out of nine Bank of England Monetary Policy Committee members voted against the cut yesterday.

Comments

When commenting, please take note of this blog's comment policy, which is available here. Contravening this policy will result in comments being deleted before or after initial publication at the editor's sole discretion and without explanation being required or offered.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

There are links to this blog's glossary in the above post that explain technical terms used in it. Follow them for more explanations.

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

Buy me a coffee!

Buy me a coffee!

Might the choice of the members of the B. o. E. Monetary Policy Committee be such that a (submerged) policy of higher interest rates is consistently followed?

‘Caution’? Why, is some rentier somewhere buying another yacht?

Fascinating to see those sub-editors each trying hard to spin a lie, with their headlines. Talk about lipstick on a pig!

The simple answer is inflation. Rebasing the start of the century to 100, prices are UK: 192, Eurozone: 172, Japan: 114, US 1.92…. the UK does (and always has had, higher inflation). This need not be a problem – higher inflation and higher rates could, indeed, be a good set up as it makes it easier to avoid deflationary traps. But it depend crucially on what the “real” interest rate is (the amount the rate exceeds inflation).

A pound/euro/yen invested at the money market rate would become 1.92, 1.48,1.05 and 1.75 respectively. Now, a huge chunk of this period was during zero rates and QE (so real returns over the period are poor) but the message is clear – real returns (and therefore real interest rates) in the UK are much higher….. and this is (and always has been) a problem for the real economy.

One could turn this on its head and ask – “if rates have been higher in the UK, why has inflation performance been worse?”… and the lesson here is that controlling inflation by higher rates (both nominal and real) doesn’t work. We need other ways to control inflation (step forward MMT and tax).

PS The data might be a bit sketchy – it is from AI sources and the first few goes were clearly gibberish. These look correct to my eye but…..

Thanks

The data looks right

You’re right that controlling inflation through interest rates is clearly flawed.

The idea is that it puts pressure on companies and households, and constrains demand. In a marketplace dominated by domestic demand, where profit-taking is being enabled by excess demand, then putting pressure through interest rates should dampen demand, make companies trim profit margins to restore demand, and reduce inflation.

However, if demand is relatively inelastic (e.g for non-luxury foods, energy, housing, etc), then demand may change little if pressure is increased and interest changes may not help.

If sufficient demand is present in international markets then interest rates (which only put pressure on domestic demand, really) then changes in domestic demand may have little to no impact on prices, in particular setting a floor at which point domestic buyers largely stop buying but profits can be maintained through international sales.

Worse still, if those higher interest rates increase the cost of production or holding inventory substantially (e.g. cars or other products with long initial cost to revenue delays), then prices may be increased, not decreased, as producers are forced to pass on costs, worsening not alleviating inflation.

Further, as safe returns on cash savings are increased, there is a disincentive towards investment because the risk-free rate of return is higher and riskier projects (due to financing costs) get risker, making more projects uneconomical.

The Bank of England has one mandate and one lever, and that lever doesn’t do what it’s intended to do.

ISTM that high interest rates do constrain “real” businesses, the SMEs that actually improve people’s lives, but they don’t constrain wealth-extracting corporations, who can borrow, buy, dismantle, asset strip, extract their dividends, bonuses, and borrow to buy their own shares then use the debt to justify going into an extractive administration/bankruptcy.

Or if they are landlords, put up the rent, getting different tenants in if the old ones cant afford the new rent.

And of course high interest rates don’t stop wars or pandemics or climate change catastrophes.

Has Mr Bailey ever explained why the UK consistently needs higher rates than other countries?

Precisely.

The minutes of the BoE meeting indicated they feel the current rate is not restrictive and therefore not having much impact. ‘Restrictive’ has to be relative to something, and I don’t think they have the right reference points.

Many adults care most about rates when they have a mortgage. Take a 25-year mortgage period and add a bias towards earlier on when, relative to earnings, it is likely to be bigger and you’ll have less equity, resulting in a worse rate. The challenges are higher for early to mid mortgage households, with others somewhat less affected by higher rates.

If we look at the last 15 years, rates were lower for the first 12 years, and only higher since early 2023. Those finishing a 2 year fix may find a lower rate. Those who had 3+ years fixed face a higher rate. Those who had 5 year fix may be facing an increase of 3.5% from their previous rate. That is, undoubtedly, restrictive.

Another point of reference would be European Central Bank rates: 2.15%. Compared to that also, 3.75% IS restrictive.

That this interpretation is used by the likes of Mann and Pill to dismiss the risks of a ‘non-linear’ deterioration (from unemployment and/or company dissolutions) shows that they have a clear bias in favour of higher rates and choose not to accept the evidence of increasing risk that is placed in front of them.

It’s hard to justify that. Worse, even members who noted sticky inflation concerns reducing and risks of non-linear deterioration increasing, stated a view that a ‘neutral’ interest rate was around 3%. Given the 2% inflation target, members who supported a decrease think that 1% real-terms interest rate is ‘neutral’.

Think about that for a moment. Positive real-terms interest rates mean debtors pay more to service debts, while savers gain more in interest than they lose to inflation. This is a net transfer from poor to rich. And yet the evidence is clear – all BoE committee members think a positive real-terms rate is ‘neutral’.

I prefer the European Central Bank position, where its current rates relative to inflation suggests that a ‘neutral’ rate is actually that – neutral in real-terms.

Agreed

Yes.

Surely, a neutral cash rate should be equal to expected inflation (ie. 2% with our current inflation target). Long gilts? 3%, perhaps?

Now this might have implications for asset prices…. but there are other tools available if you are prepared to use the tools from 50 years ago and move beyond Friedman’s (wrong) observation that “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon, in the sense that it is and can be produced only by a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output.”… and the implication that controlling its price (interest rates) is the only way to deal with inflation.

Deafening silence in the MSM about the ECB Rate. And from MPs, whose economic ignorance is almost boundless.