A savings glut creates global economic instability, and that's precisely the problem the world's got right now. The question is, what are we going to do about it?

This is the audio version:

This is the transcript:

The world has a glut of savings.

There is too much surplus cash in this world.

You might think that's a problem you'd like to have, but actually, it's causing massive global financial instability, and that's a problem.

The result is that we need to talk about what's going on, where is it going on, how big is the problem, what are the consequences, and what can we do about it? These questions all need answers because the world's savings glut might cause the world's next financial meltdown.

A savings glut is a simple situation where there is more cash, in particular cash, being saved in the world, in excess of the world's desire for investment.

In other words, we are creating global surpluses of income, whether that be household income or business profits, that are not being redirected into constructive investment for the benefit of human beings. The result is that we actually have cash, in particular, floating around the world in excess of anyone's needs.

And that is a phenomenon that is creating real problems. Real problems like asset bubbles and financial crises, and it's also, and we saw this over the last 15 years, forcing interest rates too low, until Central Banks react by forcing them too high, which then creates a tension inside financial markets, which is very hard to manage. This problem is very real and a threat to our well-being.

The idea of a global savings glut was first really recognised by US Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke in 2005. What he said then was that there were too many savings in the world and they were pouring into the USA from countries with surpluses and high savings rates, and that, he suggested, was contributing to a bubble in US house prices.

Well, we know what happened then. We had a global financial crisis as a consequence. Ben Bernanke was right. These things have the power to destabilise the world's finances. Savings are a problem.

But who is it that's saving too much? Around the world, there are a number of countries which are very clearly doing so.

China is the biggest culprit. It has savings rates that are far too high in proportion to the investment that is made in that country. And there are two factors to this.

One is that Chinese companies are really very profitable. Wage rates are low. Sales potentials are high. Profits are high. Reinvestment is relatively low. As a consequence, China's companies have simply got piles of cash.

But there's another problem in China as well, and that is vast numbers of people need to save for their old age because there is no effective social safety net in that country. There are inadequate pensions, and so it puts aside vast amounts of money. The Chinese people save for their futures in a way that actually creates a cash pile, which has to go somewhere.

There are other countries which contribute as well. Germany and Japan are particular countries where this is a problem. Germany, because it is right in the middle of the EU, of course. It is benefiting from the fact that the whole of the European Central Bank's monetary policy is effectively designed around German needs, and German people are saving in large amounts as a consequence, largely off the back of extracting value from other European states.

But also, they are saving because they, like China, have ageing populations who are worried about their future, and that is the Japanese phenomenon as well. Japan has a very definitely ageing population and a very small birth rate, an issue that we've touched on in other videos of late, and the consequence is very high savings rates for retirement without anybody actually thinking how they're actually going to hire the help they need when these people really are old. Germany and Japan, therefore, are contributing to this issue.

But so too are oil-rich nations. Countries like Qatar and Brunei, for example, make massive surpluses from their oil, and they are quite clearly trying to splash the cash as fast as they can.

We see this in their investment in sports.

We see it in their investment in airlines.

We see it all over the place.

Qatar, in particular, is very good at doing this, but even so, they've got more cash than they know what to do with.

And there are another group of nations which are really contributing to this problem, and they are the world's tax havens.

Money is parked in these places. And before we get too excited about some of the more obscure ones, perhaps the biggest culprits are Luxembourg, Ireland, and Singapore; places that most people don't immediately think of as tax havens, but where the world's corporations go to brush their feet of the excess profits that they have made on which they do not wish to pay too much tax on.

But then we can also add other places like Cayman, and of course on a slightly lesser scale, places like Jersey, Guernsey, the Isle of Man, and so on; all those places that the UK is so keen to promote as locations for corporate profits around the world, as well as the illicit money parked there by so many private individuals.

So, is there a flip side? Of course there is. There are countries who run deficits, some of whom need to run deficits.

The United States is the biggest borrower, but that's not really because it borrows; let's be clear about it. Its $36 trillion national debt does in part exist because people like Donald Trump have insisted on running the US government on the basis of deficits, because he's so keen to give tax cuts to the wealthy. But the real reason why the US runs such a big deficit is because the rest of the world wants to literally buy its dollars. They will give people in the US goods and not actually basically convert the resulting dollar balances that they create into their own domestic currencies, and trade imbalances arise as a result.

So the US ends up as the biggest borrower in the world, and the UK is also a major borrower, and that's partly because our governments, too, by habit, run deficits. But it's just as much because we have the City of London operating almost as a state within the state in the UK, and in that capacity, the UK is dependent upon the kindness of foreigners to run its deficits. But those foreigners, whoever they might be, from wherever they are in the world, are still more than willing to deposit funds in sterling in the UK, and the consequence is that we, too, are significant borrowers.

Perhaps more significantly, and I think that we should emphasise this, developing nations need to run deficits. They need to invest. They need to tackle the multitudinous problems that their countries face with regard to a lack of infrastructure, with regard to an incapacity to deal with climate change, to deal with the adaptation that that requires, to promote the education and healthcare that they need. All of those things need investment. But bizarrely, because of the options that are available within the United States, the UK and tax havens, where funds can be located without exposure to real risk, the consequence is that developing nations who need investment aren't getting it.

There is an actual shortage of investment in these countries, even though the world is awash with money, and in the middle of all that the UK is saying it cannot afford to spend 0.7% of its GDP on aid now, and it's cutting that to 0.3%, which just makes the problem worse.

What are the consequences of all this?

There is no doubt that the global financial crisis of 2008 did happen because far too much hot money - cash - moved into that country, needing to find a home, and that money was used to lend to people, to inflate house prices and that created the mortgage bubble which brought the world's banking system to its knees in 2008. That was the flip side of having too many savings.

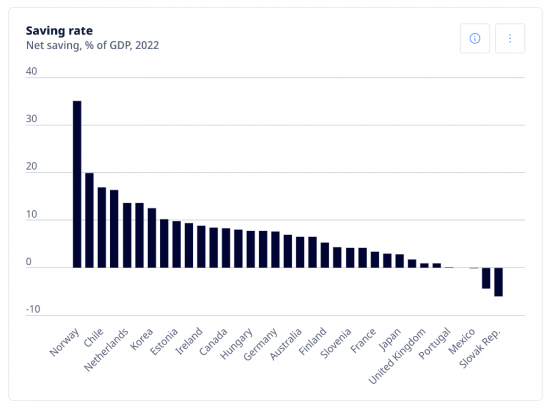

But there are other flip sides as well. There is, for example, a problem with equality, and to some degree, we can see this in this chart, which is a map of where the savings glut is located.

There are clearly too many savings in Norway. The world likes to say that Norway's Wealth Fund is a great asset, but is it? Is it just a sign that, actually, it's made so much money from oil that it's sitting on a pile of money it doesn't know what to do with? The Norwegian Global Wealth Fund is invested outside Norway and has simply inflated stock markets. Has it really created asset investment? It's very hard to say.

There are other countries in there which are clearly problematic. For example, the Netherlands has a massive savings rate. It is a tax haven.

Korea has a high savings rate because, like China, it doesn't have an adequate social safety net.

Ireland is a tax haven.

Many of these countries that are at the left hand side of this chart, and this is a chart of OECD countries, by the way, because this data is harder to find for the whole of the world on a reliable basis, let alone put up on the screen, but the point is that the countries which are aberrational and have high savings rates do so because they have structural failures within them.

The countries that are saving normally, Canada, Hungary, Australia, those that are in the mid-range, they're not creating much difficulty by having a 5%, or thereabouts, savings rate.

The countries at the right-hand end, Mexico in particular, need to run deficits to deal with the problems that they face. So we have a problem. And we basically have a glut, which is why there are so few in deficit and so many in surplus. We need to understand that.

So, what is the consequence of this, and how do we manage it?

The consequence is instability.

We manage it by trying to reduce savings.

That is the consequence that all these countries that have savings in excess of their needs to make actual investments in their real economies need to address unless they are willing to redirect the funds constructively to developing countries.

So reducing savings is essential.

The reduction in financial flows which might cause harm is essential.

We need to increase real investment.

And we need to reduce the risk of financial meltdown.

How do we do that?

First and foremost, we need to create the social safety nets that will make sure that people feel secure in their future.

That is vital. Without that, China will still see these surpluses and so will other countries like Korea, and Japan, and Germany, and so on.

We need to correct for that.

We need to increase pensions for older people, so they do not need to save as much.

We need to tax wealth more. This is an issue that I tackle often, but it's a simple, straightforward fact that unless we do redistribute wealth within countries by using taxation as the tool which is most readily available for this purpose, there will be excess savings, and those excess savings will destabilise economies.

We need to increase aid to developing countries.

We have to do that to make sure that they can really invest, which is the necessary flip side of this saving surplus.

And, of course, we still need to tackle tax havens, not because they might now be a problem with regard to their opacity, because to a very large degree, that problem has been solved, partly as a consequence of work that I did, a decade or so ago with the OECD, to open up these places so that we know who saves in them and which companies use them. But they still exist as locations where excess savings are stored, and that is a difficulty. They are instruments for the savings industry, and unless we solve that problem, they will still create financial instability.

And we need to tackle the problem of reserve currencies: the problems in the US in particular, but also in London.

And we need to tackle the problem of having a major financial centre in London, which is the particular problem that the UK faces.

Ultimately, though, we need to increase investment. Investment to save the planet with green, tax-incentivised funds.

We need to invest more in housing that people need.

We need to invest in those things that will tackle the harms that are already locked in as a consequence of climate change, and in particular, things like flood risk.

We need to invest in education and healthcare, particularly in developing countries, so that pressure for migration is reduced.

We therefore need to increase the income of those places, again to make sure that people do not want to migrate in the way that we are seeing, and which is causing social stress.

We need, in other words, to reduce inequality, within and between nations.

And we need to look at what this means for growth. Not growth for growth's sake, but growth for the sake of tackling the world's needs.

That does ultimately depend upon our ability to tackle climate change.

But there is no shortage of tax revenues to deal with these issues. The world's savings are not taxed enough. We could tax them more. We could, as a consequence, collect all the money that is required to ensure that, literally, the world's problems can be solved.

The world's savings glut is, at present, causing a massive problem. It could, if we addressed it properly, be the source of our salvation. These resources could be put to good use. The choice is available to our politicians. The question is, will they take advantage of this situation?

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

There are links to this blog's glossary in the above post that explain technical terms used in it. Follow them for more explanations.

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

Buy me a coffee!

Buy me a coffee!

“Chinese Work Less For Longer Retirements”

Might the article below, which has the above title, be relevant?

https://www.moonofalabama.org/

The world is awash with idle capital. Vast pools of wealth are sitting inert in bank accounts, pension funds, tax havens, and sovereign wealth vehicles — earning little, helping no one, and fuelling instability. Rather than powering progress, this glut of savings is inflating asset bubbles, entrenching inequality, and starving the global South of desperately needed investment. The crisis is not a shortage of money — it’s that money is in the wrong places, doing the wrong things. Instead of calling for less saving, we should demand smarter use. It’s time to turn these untapped resources into a force for global good.

Establish a multilateral institution — backed by surplus nations, sovereign wealth funds, and the IMF — with a singular mission: channel global savings into infrastructure, climate resilience, and green energy in the Global South and beyond. Returns would be real and long-term, and the risks could be underwritten by a global insurance fund. Instead of Norway’s trillions sitting in stock markets, why not solar rooftops in Nigeria?

Trillions in pension wealth are currently trapped in passive financial instruments. Regulatory reform could require a fixed percentage of pension assets to be directed into affordable housing, clean energy, care infrastructure, and healthcare innovation. This would still deliver long-term returns — just more usefully tied to the wellbeing of people and planet.

Developing nations often face prohibitively high borrowing costs, even when they desperately need investment. A global guarantee mechanism — supported by surplus nations — would reduce risk for private investors willing to back social infrastructure, climate adaptation, and economic transformation in poorer nations. It could leverage every dollar of guarantee into several dollars of real-world impact.

As suggested, excess savings often correlate with extreme wealth concentration. A coordinated global minimum wealth tax — starting at just 1% on assets above $50 million — would not only rebalance economic power but generate the public capital to fund education, healthcare, and clean water for millions.

It’s time to rewrite the rules of global finance. The current system rewards idle hoarding and speculation. Instead, we should use capital controls, transaction taxes, and macroprudential tools to discourage financial engineering and encourage productive, long-term investment — especially in underserved regions.

The article rightly highlights Luxembourg, Ireland, and Singapore — not just tiny islands — as vaults for cash that never sees the light of day. These jurisdictions should face coordinated penalties from the G20 unless they mandate full transparency and redirect those funds into global development goals. Transparency alone isn’t enough anymore — it’s time for redirection.

The IMF’s SDR mechanism is underused and poorly distributed. It could be dramatically expanded to issue new liquidity tied to green and social investment benchmarks — essentially printing money not for bailouts, but for planetary survival. These funds could be loaned interest-free to low-income nations meeting investment criteria.

The savings glut shows the world has the resources for radical fairness. A permanent global fund could provide grants (not loans) to build roads, schools, clinics, flood defences, and clean water systems in the world’s most deprived regions. If Qatar can build stadiums for FIFA, it can help build hospitals in Madagascar.

In short: don’t shrink the ocean of capital — steer it.

The world doesn’t have a money problem. It has a moral and political imagination problem. These savings — this glut — should be a lifeline, not a ticking bomb. The time for austerity is over. The age of directed abundance must begin.

Thanks

Meanwhile, the IMF recommends working more for longer, so the state has to support you less

https://www.theguardian.com/money/2025/may/23/ludicrous-unfair-older-workers-react-pressure-delay-retirement

It’s the madness of the market…

Yet another symptom of the Neo-liberal world we live in.

We create pots of cash that become like effigies and then we worship them whilst the world crumbles around us.

In doing this we are imitating the rich who have everything they need. In imitating the acquisitive behaviour of the rich, the majority of us will rob ourselves of our futures.

Making effigies out of accumulated money or ‘net worth’ – just a number – and letting it sit there to be displayed and worshipped as a deity thwarts the real power of money to solve problems and get things done.

This ties in with another strong Neo-liberal trait – the denial of the state and its sovereign money making and problem solving capacities in favour of those who amass wealth from debt and who to tend exploit problems rather than solve them.

I think that your post is spot on.

Thanks

I’m part of the savings glut having saved into a personal pension for over 40yrs. It is pay for my and my family’s life when i can no longer earn, It is not for you to tax or experiment your fanciful ideology on.

You got a massive state subsidy. It is most definitely my right to discuss that. Your selfishness is staggering.

“You get a massive state subsidy”..i would call it encouragement to fend for one’s self and not live off the state. Also full taxes are paid on money taken out and on death. The point i make is for the majority of people where this “glut” you talk about is really folk trying to even out income generation and expenditure over their life. Pension saving/ investment, call it what you like but it is just being entirely responsible for one self and their dependents. So no “my selfishness isn’t staggering at all” neither are the aspirations of millions of other pension savers.

You typify the small-minded idiots who are driving this country towards fascism.

But I can almost guarantee you welcome them.

As far as I understand it what has been proposed has been to eliminate higher rate tax relief of pension contributions, which won’t affect the majority of ordinary workers and would make things more fair, and to encourage investing pension savings into real life investment, which would still receive an appropriate return, into infrastructure and things like health and education, which would benefit us all. We need to look at things from a societal point of view not an individual point of view. That’s what got us into this mess in the first place

All issues of excess savings, inequality, undertaxed wealth, are symptoms. The cause is the central banking cycle, which dominates all other economic cycles. Central banks stimulate to escape recession and financial crises. Some of the credit seeps into savings, some into business and household borrowing.

The result is that the ratio of interest expense to economic activity (measured by GDP, not brilliant but it’s the best we’ve got) rises. Even when interest rates for depositors are below the inflation rate, rates paid by borrowers are invariably above the inflation rate. Commercial banks have engineered ever-wider quality spreads over the last quarter of a century.

Based on 2018 data, I calculated that the global interest paid to GDP ratio was 21%. Puerto Rico defaulted when its ratio of interest on public debt plus pension debt reached 37%. We do not know where the upper bound for this ratio is, but logic says that it can never reach 100% because then the world could not house or feed itself.

The slow-running central banking cycle is therefore delivering an ever-less serviceable business and household debt burden. It has taken eighty years of post-1945 economic policy to get this far. In 1945 the UK’s private debt was about 12% of GDP (public debt was some two and a half times GDP). Now private debt is three times GDP and public debt is only around 100% of GDP.

All the arguments about budget deficits, taxing the wealthy, savings gluts, etc ignore this slow-burning problem. Central banks are driving the interest paid to GDP ratio up and therefore driving the world towards another financial crisis.

The immediate issue is Trump and tariffs which will precipitate the next global recession. Private equity, shadow banking generally, and the debt burden faced by businesses and households will all contribute to a differently-shaped financial crisis. Then central banks will respond with stimulus measures and drive the world further up against the financial system limit.

Needless to say, nobody in the financial establishment wants to think about these slow trends.

These trends are very slow, taking decades to unfold.

I wish you would show your workings.

My workings for the interest cost to GDP ratio were published in my book The Financial System Limit, see sparklingbooks.com/finance.html

The discussion of alternative courses of action is in another book, on the same web page

Would you and D J Kauders end up on the same page if real progress was made towards better tax collection, thereby reducing harmful imbalances and enabling productive public investment?

I am not sure what your question means. Can you add some content to it, asking specifically what you are asking about?

Sorry Richard. I’ve got J D Kauders wrong. He’s talking about private,and not Government debt. And I’m clearly struggling with the savings totals. I need a lie down.

🙂

Brilliant 🙂

It’s a no brainer.

If there were a decent pension and lower retirement age people would not need to buy to let, people would feel safe to spend, and wouldn’t feel the need to hold onto jobs.

Thus releasing a hoard of cash piles, releasing homes and jobs for the next generation who are blocked out from life and using their youthful strength to make the Green transition we need.

The challenge is to get real value from these savings

The point about Japan is a good one

People there will have lots of money in there old age but nobody will be there to provide the care they need even if they can pay for it

Cash is King when there is uncertainty. Re 2007/8 was a build up of private debt (no savings involved) and lack of fiscal policy to put breaks on asset price inflation – Dirk Bezemer’s No One Saw This Coming (well some did for very good reason) https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/15892/ More cash equals more stable base, avoid Minsky moments, could it be in better places? Better incentives required…

If anyone here feels their savings are a burden, I am willing to take some of the burden off them.

I like to help people.

Richard

We did have the global savings glut that Bernanke identified. But it has vanished now.

Global bond yields – both nominal yields and inflation-linked yields – have soared since 2021. The yield on 30 year UK gilts is now 5.5%, the highest level since 1998. The story in the US is very similar. We can debate causes and consequences, but the market evidence is very clear: there is not a savings glut right now.

Politely, please don’t waste my time talking garbage here, when there is such a thing, and it’s very real, and it exists now.

As Chris Hedges very presciently said “our ruling elites kneel and force us to kneel before the dictates of the global marketplace”

Th philosopher Spinoza who said we -mainly and wrongly -worship the gods of the tribe or the gods of the market place.

That hasn’t changed in 300 years.

As you say, being old is getting more and more expensive, mainly because people are being old for longer and longer, so the natural reaction is to save more for your old age. The only real alternative is to demand that everybody drop dead at the age of 67.

I will be a goner very soon, then.

Let me just get my coat…..

I’ve been doing some digging to try to get my head round the extent of the issue in the UK. I think it looks something like this. Do you think it’s about right?

Household savings (bank deposits) £2.0 trillion

Includes current accounts, savings accounts, and ISAs.

Pension funds £2.0 trillion

Mostly invested in bonds and global equities; only a small share supports UK economic activity directly.

Corporate cash holdings £0.5–0.7 trillion

Retained earnings and liquid reserves of UK non-financial companies. Often underutilised in terms of productive domestic investment.

Estimated Total : £4.5 – £4.7 trillion

Total pensions are much higher: that figiure is seriously understated accpording to gross OND wealth data.

Total pension wealth seems to be assessed at around £4.2 Trillion, and was considered to be £6.4 Trillion before a recent methodology change. But this includes future liabilities doesn’t it? Isn’t the real money that’s sitting idle, that could be used for productive investment, closer to the £2 Trillion? Let me know if I’m getting boring. But I’m just trying to understand.

I am using the total household wealth data, which as far as I know has not been updated.

It strikes me that this is really a problem that can only be properly solved by global fiscal cooperation, in taxation and in economic distribution, which also applies to climate change and resource depletion.

No doubt, individual wealthier nations with cash surpluses could chip away at the problem by increasing foreign aid and lending to developing countries on a basis that does not lead to unsustainable indebtedness in the borrower countries. I think this would be a very good thing, although, sadly, the indications are that we are moving in the opposite direction, at least in the UK and the US, driven, as I see it, not by need, but by the requirements of sustaining our declining western imperialism.

But across the world, I think there are very few politicians or business “leaders” or bankers who actually seem to be able to look at issues like inequity and climate change and the associated impending mass migrations and resource depletion and recognise them as global problems that can only be solved by concerted and unified effort by the whole of mankind.

We simply haven’t reached a level of intellectual maturity as a species to be able to resolve our almost universally unnecessary conflicts in all spheres both rapidly and permanently so that we can focus on the planetary issues that are going to destroy us if we don’t address them.

And even when we do manage to unite to some extent on an issue, (largely intellectually rather than functionally), as we did with the Paris climate accord, we show ourselves incapable of following through with the actual actions needed to realise our agreement.

Local political considerations, levering for national and competitive advancement and, above all, greed, step in and scupper our intent.

And the only thing I can think of that might change that is universal and enlightened education, untainted by propaganda and disinformation that brings the global public to a similar level of knowledge and does the same for the global aggregation of politicians, academics, professionals and business people

I once naively hoped, what seems a long time ago, that the Internet might be the vehicle that would enable us to achieve that, and in those very early days, when virtually everything on the internet was collaborative and cooperative and largely free of commercial or neoliberal exploitation, it seemed possible.

But I doubt that the internet is any longer a viable entity for achieving that. It is just another commercial carnival cruised by the world’s economic sharks and any attempt to clean it up would req

It strikes me that this is really a problem that can only be properly solved by truly global cooperation, in taxation and in economic distribution, something which also applies to climate change and resource depletion.

No doubt, individual wealthier nations with cash surpluses could chip away at the problem by increasing foreign aid and lending to developing countries on a basis that does not lead to unsustainable indebtedness in the borrower countries. I think this would be a very good thing, although, sadly, the indications are that we are moving in the opposite direction, at least in the UK and the US, driven, as I see it, not by need, but by the requirements of sustaining our declining western imperialism.

But across the world, I think there are very few politicians or business “leaders” or bankers who actually seem to be able to look at issues like inequity and climate change and the associated impending mass migrations and resource depletion and recognise them as global problems that can only be solved by concerted and unified effort by the whole of mankind. Or even to comprehend the implications of failing to do so.

We simply haven’t reached a level of intellectual maturity as a species to be able to overcome our greed, live with fact and truth, and resolve our almost universally unnecessary conflicts in all spheres both rapidly and permanently so that we can focus on the planetary issues that are going to destroy us if we don’t address them. Inequity, as much as climate or resources, seems to be one of those issues.

Even when we do manage to unite to some extent on an issue, (largely intellectually rather than functionally), as we did with the Paris climate accord, we show ourselves incapable of following through with the actual actions needed to realise our agreement.

The only thing I can think of that might change that is universal and enlightened education, untainted by propaganda and disinformation that brings all of the global public to a similar level of fundamental and necessary knowledge and does the same for the global aggregation of politicians, academics, professionals and business people.

But, as Eliot said, “humankind cannot bear very much reality.”

Whenever we approach global problems, local political considerations, levering for national and competitive advancement, untruth, selfishness and, above all, greed, step in and scupper our intent. And we create counterproductive mythologies, prevaricate and procrastinate to avoid the social, economic and individuals costs of facing the problems.

I once naively hoped, in those early Mosaic days, that seem a long time ago now, that the Internet might be the vehicle that would enable us to achieve that universal education, and in those very early days, when virtually everything on the internet was collaborative and cooperative and largely free of commercial or neoliberal exploitation, it seemed possible.

But I doubt that the internet is any longer a viable entity for achieving that. It is just another commercial carnival cruised by the world’s economic sharks and any attempt to clean it up would require an unattainable level of universal cooperation and meet immense greed-driven resistance.

I fear that the savings problem faces the same issues.

Thanks

The Financial System Limit is an elegant way of saying total debt cannot expand to infinity. As Padraic says, it is as important as climate change and resource depletion. A well-known FT economic journalist tried arguing with me that it doesn’t matter as all interest payments net out across the economy, costs for some and income for others. That ignores the damage done to those who are underwater with debt, which we will probably discover following the next global recession.

Richard,

What a great set of thoughts from you all.

I do think humanity is hopeless with big globalised issues. Our politicians play their parts with one eye on local interests.

Mervyn King the BoE Governor thought that the reality of the prisoner’s dilemma was a real issue for many countries. They are frightened to make the first ethical move on an issue. Personally I think this is too generous an interpretation of the behaviour of many large states.