There is a whole raft of new employment data out this morning from the Office for National Statistics, much of it suggesting that we are moving into states of bigger flux.

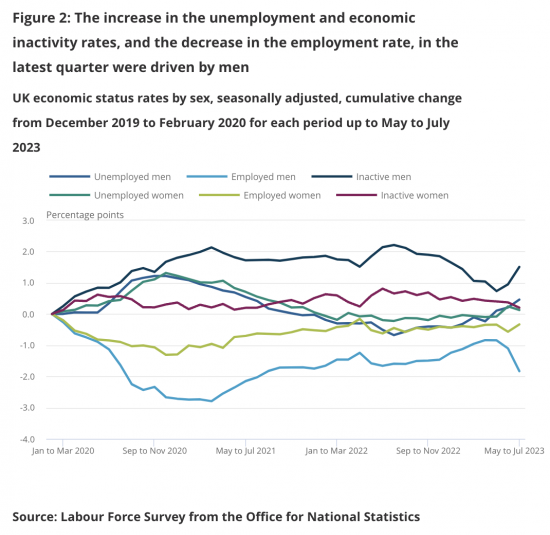

For example, unemployment is up:

It seems that male unemployment has risen significantly. That. of course, is what the Bank of England wanted: it thinks rising unemployment will curb inflation.

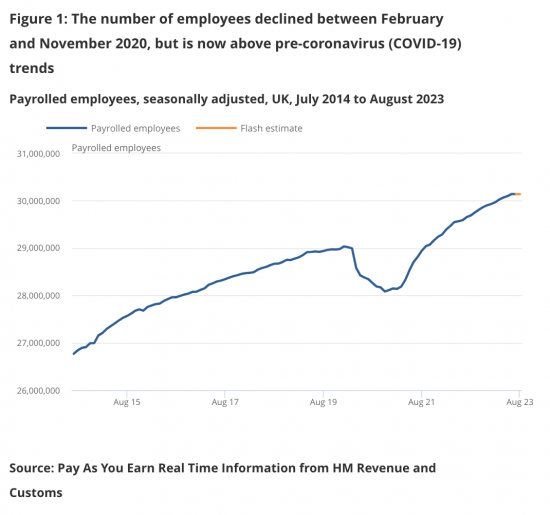

The number of employees has fallen slightly as a result, breaking the post-Covid trend:

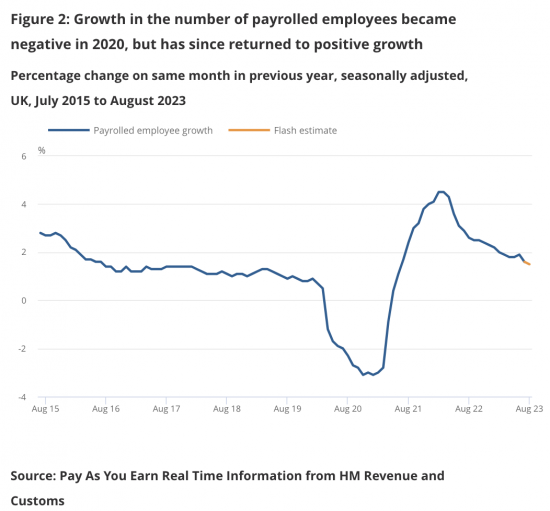

Looked at in more detail, the rate of growth in employment is falling, steadily:

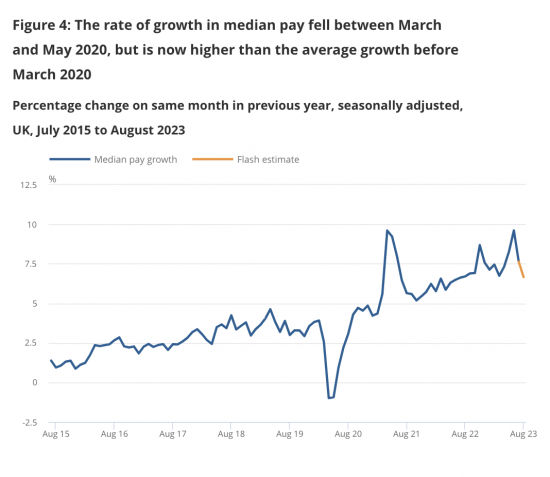

That said, provisional data suggests that the rate of increase in pay is also falling - which is especially worrying as that will leave people well behind their pre-inflation earnings:

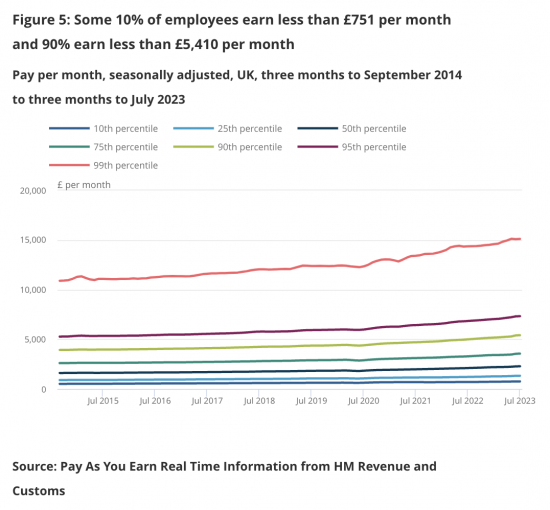

And in news that will surprise no one, the best off are doing best:

There are some big consequences of this news. For example, because the annual growth in employees' average total pay (including bonuses) from May to July 2023 was 8.5% that sets the benchmark for pension increases next year - pushing the new state pensions to £11,500 per annum. This will put pressure on Hunt and explains why the Tories are not committing to the triple lock in future.

There are also some deeper messages in this data. Fore example, I noticed this, which headlined the ONS report:

Early estimates for August 2023 indicate that the number of payrolled employees rose by 1.5% compared with August 2022, a rise of 449,000 employees; the number of payrolled employees was up by 3.9% since February 2020, a rise of 1,120,000.

I could not help but wonder where these people all came from socially when I noted this comment:

Between August 2022 and August 2023, there was a decrease of 41,000 payrolled employees aged under 25 years; during the same period, payrolled employees aged 35 to 49 years increased by 174,000.

The answer has to, of course, be found in migration data. On this, the ONS has noted:

Total long-term immigration was estimated at around 1.2 million in 2022, and emigration was 557,000, which means migration continues to add to the population with net migration at 606,000; most people arriving to the UK in 2022 were non-EU nationals (925,000), followed by EU (151,000) and British (88,000).

A lot of migration is, of course, related to study, and so by no means all arrivals work. However, some do. The growth in UK employment is then in no small part because of migration, and yet we still remain short of key employees.

The evidence that we are not investing enough in people in this country is very strong.

As a result, whatever this data shows, we are also underpaid: we have the ability to earn more if only the investment was made is the point that I am making. But that does not happen. And that is not because of migration - it is because UK employers take such a short-term view of any form of staff training.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

The detail of who is working and specifically what they are doing are two very interesting questions.

A clearer understanding of these two questions then might enable us to understand why this country needs a yearly injection of 1-2% additional people into its workforce.

I may be oversimplifying but why does a nation that was broadly self-sufficient in terms of its workforce in the 1970s now need net migration of 300,000 – 600,000 a year?

I am tempted to suggest that forty years of neo-liberalism have created a society that is so toxic that it destroys people who have to be constantly replaced.

The replacement birth rate was higher in the 70s and we weren’t self sufficient then either, and haven’t been since at least the Second World War and Windrush in the 50s.

In David Edgerton’s history “The Rise and Fall of the British Nation” his view of the available statistics was that in the 1970s by most measures this country was the most self-sufficient it has ever been.

Working in Industry at a time when you could buy a house comfortably on an average wage and still afford a social life that is certainly what it felt like.

It is not the principle of immigration that concerns or puzzles me, what does not add up is the quantity and the apparent constant very high numbers of new workers needed, in an economy that has been struggling to barely tick over for the last thirteen years.

That is why it would be very interesting to have a more detailed breakdown of workers in the whole of our economy by age, geography, social class, gender, education, place of birth, etc. I know the ONS goes some way down this route but generally it seems to be an area that we are remarkably incurious about.

I share your curiosity

We have no one to do what is needed and yet everyone is busy

Are they all doing what the late David Graeber called ‘shit jobs’?

How many add no real value to society?

It seems like a massively important question.

There are a huge number more job roles now than there were. As a child in the 60’s, our doctor’s surgery consisted of our doctor. No receptionist, no practice nurse or practice manager, nothing. Similarly in the hospitals there were junior doctors, senior doctors and nurses, sisters and matrons. There were very few admin staff. Same in education – each class had a teacher. My junior school had a school cook, a head teacher and a cleaner in addition. In social care, people were looked after by their families, very few had proper care.

I am not suggesting for one moment that was better. But it was different.

There were also vast numbers of jobns that have disappeared

Middle managers

Miners

Typists

Half a million railways workers

40,000 at HMRC

So, swings and roundabouts

The latest demographic analysis I can find regarding the UK workforce composition is from data drawn from the last Census in 2021,and which was published on 31st March 2023: https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/uk-population-by-ethnicity/demographics/working-age-population/latest#:~:text=80.7%25%20(30.2%20million)%20of%20working%20age%20people%20were%20white,from%20the%20'other'%20ethnic%20group.

It’s problematic as such granular data has to be drawn from multiple sources, and as the ONS lost a lot of its experienced staff in the move to Newport, such delays in analysing and publishing the data will become common place.

‘Some 10% of employees earn less than £751 per month’

Is that likely to be related to the fact that employer’s NI kicks in at £758.01 per month? Is that an argument for increasing the threshold to £12570, the same point as employee NI contributions start? Or, better still, doing away with employer NI all together?

Could be some people gaming NI contributions. Taking a low salary and topping up through dividends.

See tomorrow morning’s blogpost ion the Taxing Wealth Report 2024

What does post-covid trend mean?

Covid hasn’t gone away.

Accepted…I meant since lockdowns

Covid is definitely still around

There was a very interesting Covid Action zoom yesterday evening, with Stephen Reicher giving a report on the uncertain state of covid in the UK now.

There are no random population studies now, but the ONS said they were going to increase their surveillance. The obvious question there is from what.

So I checked their statistics and the last infection survey was 24th March this year. next release discontinued, so they haven’t been checking for nearly six months.

Really easy to increase surveillance from zero.

If anyone wants to watch it, it will be on Covid Action’s facebook page over the next few days.

The Scottish evidence is relevant.

They test Covid in sewage. England has stopped. The rate is rising in Scotland.

An ageing workforce and a lower birth rate has some effect. Also as stressful working conditions and low pay are increasing then ‘work avoidance’ by dropping out and working on the side cash in hand and casual labour not officially recoded is increasing. Also (guessing here) women are prepared to put up with more rubbish conditions and low pay rather than men do so they tend to get the new gig vacancies.

I am not sure I but such stereotypes

Bill Hughes

Also (guessing here) women are prepared to put up with more rubbish conditions and low pay rather than men do so they tend to get the new gig vacancies.

Women have always had to work in rubbish conditions and for low (or non existent) pay. But I am not sure that women make up the majority in the new gig vacancies – Uber drivers? Deliveroo staff? Pimlico plumbers? I think not.

The 70s v. 2020s comparisons … Wonder if my highly gendered personal recall has any links to this discussionr. I joined the workforce in the mid-70s – first p/t (student) then f/t. By the end of the decade the equalities legislation was in place but hadn’t really started to percolate into pay packets – particularly not in the un/under unionised “girlie jobs” I did as a student: retail, hospitality, childcare – significantly lower paid then than minimum wage would put them now, but otherwise not unlike the current gig economy jobs with their pay and conditions. However, this also extended to graduate jobs where my two degrees got me less than my male colleagues’ lower (in number and often in quality), qualifications got for them. So my earnings were nowhere near enough to pay rent on anything other than a shared room in a big flat ie:continuity with student life for a further 5 years – I did then take out a mortgage, but only because I had just inherited the deposit from my grandmother – I couldn’t have done this under my own steam/earning capacity. Meanwhile my male non graduate friends who had gone into highly unionised skilled manual work (electricians in particular) were certainly earning well, as were the male graduates and just TWO of the women (one of whom who was in the first intake into her firm to include women) in what had been traditionally male professions….. but which became 50+% female entry only a few years later…. yes, accountancy and law.

Nearly everyone I know on the wrong side of 50 wants out of work or to do less hours.

The job is paying too little, everything is in a mess and nothing works anymore. Everything takes longer and is of lower quality. Yet there is so much that needs doing and much of it could be very satisfying.

If you are like me and your kids are at Uni, that’s the only reason to put up with anything at the moment.

However, instead of addressing low pay, poor pensions, high interest rates, self defeating policy objectives and the CoLC, what we’ll get is probably another book about how lazy we are as a nation and more shitty ‘nudge’ policies to kick us into being the working poor.

Sod football, the Ashes or even the rugby – the only thing that has ever come home in this country is its empiricism, now turned upon itself – England – a country that consumes its poor and vulnerable, defeats its young and spits them into the bin.

Appalling.

Mine have now both left Uni and I am signed up fir serval more years….

Am I the odd one out?

No – I’m sure I’ll be joining you in three-four year’s time.

Anyhow, it’s all in the Tories Adult Social Care plan to make our kids stay at home and look after us because there are no new affordable places to live and no good jobs either.

Both my sons are now around again – and both have work (thanlfully)

That fits with my observations over the last 10 years. The over 50s looking to retire as soon as they can, even if that means living on less. 20 and 30 year olds looking to work from home and/or be self employed. Both groups driven by ever poorer working environments, job insecurity, minimal investment in equipment, training and skills, plus low pay. And then managers complain about lack of loyalty!

Yes there are organisations in all sectors that are different and who look after their people but too many do not. And then people wonder why UK productivity is so poor whilst we work the longest hours.

‘Shoplifting is out of control.’

[https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2023/aug/27/shoplifting-out-of-control-forget-police-stores-need-to-up-their-game.]

So is inequality.

‘I work in a supermarket and see how desperate some shoplifters are.’

[https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2023/sep/14/supermarket-shoplifters-professionals-people-poor-food.]

I wonder if those who have now lost their jobs, knew that this was always going to be the price for the BoEs/government’s strategy for “controlling inflation” and “fixing the economy”? As if the collateral damage of effectively scuppering a whole generation of people’s hopes and desires for any sort of viable future, is worth it just so that those in high places can say that they’re taking action to meet some arbitrarily assigned 2% target for inflation.

So, to the 12,000 Wilco employees, now facing the dole and zero prospects for future employment, a big thumbs up from the BoE for doing your bit to “save the economy”. Now, if they can just get the rest of the High Street retailers to collapse, and take with them all of the associated trades and suppliers, then who knows? That 2% target could be a matter of months away… and then it will be big fat bonuses all round and a guaranteed spot on those lovely red leather benches for those hard working, conscientious bods at the BoE…

I believe that over 2.5 million people are not working due to sickness due to the NHS. This must be affecting the working population. I do not see any discussion about this in the media.

I am very confused at the moment. I read wages have risen to record highs. and are above current inflation. I read inflation is coming down. I read world energy prices are falling. I then read wages in real terms are the same as in 2008. As I drive around my city I note petrol prices have risen at all filling stations some by 20p a litre. On YouTube I see reports that Saudi Arabia and Russia have cut production. Is that the reason petrol prices have risen. I have not noticed any fall in basic food prices. In fact, the opposite is true. In my long experience I know that when petrol prices go up everything else follows. What is the truth and where are we heading. ? I also read every day about firms closing . Wilko for example. Many well known multiples are closing outlets. I fear the numbers on the dole will soon rise. Because I have lived so long I can sense when the economic situation is turning bad. What is in store for us.?

We are heading for a deliberate, Bank of England created, recession

Employment data – and how they have affected me in Dorset.

Covid stimulated some Londoners to work from their *holiday* homes. Others heard about it and bought a Dorset ‘second home’. Air b&b came onto the scene and locals were more or less priced out of either renting or buying. As homes became even more enticing as gambling chips, prices have risen until buying and selling has dwindled. Now my landlord, a surveyor, has no work and expects redundancy. He wants me out so that he can sell to pay off the mortgage on the flat above mine – which he also owns as well as a house ‘up the smoke’ somewhere. Maybe the estate agent’s employee assigned to selling my abode needs to get me out soon, or his job could go too.

I have the support to find somewhere within this community but that will displace someone else who will have to travel from north of here – or find a new job; maybe new schools for the kids.

‘Everyone knows there is a housing shortage’ said a judge from a local bench recently. He didn’t know, it seems, that there are more rooms per person in Britain than there have ever been.

‘Homes for heroes’ said Lloyd George in 1918. He created ‘council’ houses with an Act the next year. The 1942 Beveridge Report identified the evils of ‘Want, disease, ignorance, squalor and idleness’. Churchill promised the NHS. Iain Macleod, Ted Heath, Anthony Crosland, Denis Healey had all seen the horrors of WW2. They were prepared to use taxation to fund a ‘welfare state.’

In contrast, Nigel Lawson was young enough to have avoided the war. Urged on by the press magnates, he cut taxes for the rich and starved the welfare state. Was that really so clever?

Good luck….and sorry you face such hassles

Unfortunately, you need to cross-check several sources to get a real world grip on economic indicators. As for oil, both the Saudis and Russia are cutting their Oil Production in an attempt to keep the price of oil north of $80 per barrel. Add to that the price of oil producer stocks, and oil futures are going up, adds weight to the conclusion that oil prices will climb again this autumn. This makes sense when you think that all oil producers face costs as Green tech gets more widespread, and Russia is using oil prices to fund it’s war in Ukraine. That’s the reality we’re facing. And, in the investing community there are opinions that say attempts to dampen down inflation may be scuppered by increasing energy costs for the next two quarters, during the time of peak demand in the global north. This will impact fuel, natural gas, and electricity generating costs, so the energy companies may have another bonanza period too this. This collection of trends might be a nail in the coffin for Chancellor Jeremy Hunt’s forecasts of falling inflation. UK inflation tends to be sticky for several reasons, and as no-one can be sure that a recession isn’t coming the temptation for suppliers to use their market power to squeeze prices up will hit consumers again. Let’s pray for an unseasonably warm autumn and winter, because our policy makers are out of ideas.

They have been out of ideas for a long time, but thanks for your comment