I had a request yesterday that I write an article explaining the national debt, most especially in the context of modern monetary theory.

Let me offer two responses. First there is this video:

That was one of the really early ones I made. The sound is not as good as I would like.

Then there is this article, which was first published as a Twitter thread in 2021. I hope that they help.

We have just had another week when the media has obsessed about what they call the UK's national debt. There has been wringing of hands. The handcart in which we will all go to hell has been oiled. And none of this is necessary. So this is a thread on what you really need to know.

First, once upon a time there was no such a thing as the national debt. That started in 1694. And it ended in 1971. During that period either directly or indirectly the value of the pound was linked to the value of gold. And since gold is in short supply, so could money be.

Then in 1971 President Nixon in the USA took the dollar off the gold standard, and after that there was no link at all between the value of the pound in the UK and anything physical at all. Notes, coins and, most importantly, bank balances all just became promises to pay.

A currency like ours that is just a promise to pay is called a fiat currency. That means that nothing gives it value, except someone's promise. And the only promise we really trust is the government's.

If you don't believe that it's the government's promise to pay that gives money its value, just recall when Northern Rock failed in 2007. There was the first run on a bank in the UK for 160 years. But the moment the government said it would pay everyone that crisis was over.

There's a paradox here. We trust the government's promise, which implies it has lots of money, and we get paranoid about the national debt, which suggests the government has no money. Both of those things can't be right, unless there's something pretty odd about the government.

And of course there is something really odd about the government when it comes to money. And that is that the government both creates our currency by making it the only legal tender in our country and also actually creates a lot of the money that we use in our economy.

How it makes notes and coin is easy to understand. They're minted, or printed, and it's illegal for anyone else to do that. But notes and coin are only a very small part of the money supply - a few percent at most. The rest of the money that we use is made up of bank balances.

The government also makes a significant part of our electronic money now. The commercial banks make the rest, but only with the permission of the government, so in fact the government is really responsible for all our money supply.

This electronic money is all made the same way. A person asks for a loan from a bank. The bank agrees to grant it. They put the loan balance in two accounts. The borrower can spend what's been put in their current account. They agree to repay the balance on the loan account.

That is literally how all money is made. One lender, the bank. One borrower, the customer. And two promises to pay. The bank promises to make payment to whomsoever the customer instructs. The customer promises to repay the loan. And those promises make new money, out of thin air.

If you have ever wondered what the magic money tree is, I have just explained it. It is quite literally the ability of a bank and their customer to make this new money out of thin air by simply making mutual promises to pay.

The problem with the magic money tree is that creating money is so simple that we find it really hard to understand. We can have as much money as there are good promises to pay to be made. It's as basic as that. The magic money tree really exists, and thrives on promises.

But there's a problem. Bankers, economists and politicians would really rather that you did not know that money really isn't scarce. After all, if you knew money is created out of thin air, and costlessly, why would you be willing to pay for it?

What is more, if you knew that it was your promise to pay that was at least as important as the bank's in this money creation process then wouldn't you, once more, be rather annoyed at the song and dance they make about ever letting you get your hands on the stuff?

The biggest reason why money is so hard to understand is that it has not paid ‘the money people' to tell you just how money works. They have made good money out of you believing that money is scarce so that you have to pay top dollar for it. So they keep you in the dark.

There are two more things to know about money before going back to the national debt. The first is that just as loans create money, so does repaying loans destroy money. Once the promise to pay is fulfilled then the money has gone. Literally, it disappears. The ledger is clean.

People find this hard because they confuse money with notes and coin. Except that's not true. In a very real sense they're not money. They're just a reusable record of money, like recyclable IOUs. They can clear one debt, and then they can be used to record, or repay a new one.

The fact is that unless someone's owed something then a note or coin is worthless. They only get value when used to clear the debt we owe someone. And the person who gets the note or coin only accepts them because they can use them to clear a debt to someone else.

So even notes and coin money are all about debt. They're only of value if they clear a debt. And we know that. When a new note comes out we want to get rid of the old type because they no longer clear debt: they're worthless. When the ability to pay debt's gone, so has the value.

So debt repayment cancels money. And all commercial bank created money is of this sort, because every bank, rather annoyingly, demands repayment of the loans that it makes. Except one, that is. And that exception is the Bank of England.

So what is special about the Bank of England? Let's ignore its ancient history from when it began in 1694, for now. Instead you need to be aware that it's been wholly owned by the UK government since 1946. So, to be blunt, it's just a part of the government.

Please remember this and ignore the game the government and The Bank of England have played since 1998. They have claimed the Bank of England is ‘independent'. I won't use unparliamentary language to describe this myth. So let's just stick to that word ‘myth' to describe this.

To put it another way, the government and the Bank of England are about as independent of each other as Tesco plc, which is the Tesco parent company, and Tesco Stores Limited, which actually runs the supermarkets that use that name. In other words, they're not independent at all.

And this matters, because what it means is that the government owns its own bank. And what is more, it's that bank which prints all banknotes, and declares them legal tender. But even more important is something called the Exchequer and Audit Departments Act of 1866.

This Act might sound obscure, but under its terms the Bank of England has, by law, to make any payment the government instructs it to do. In other words, the government isn't like us. We ask for bank loans but the government can tell its own bank to create one, whenever it wants.

And this is really important. Whenever the government wants to spend it can. Unlike all the rest of us it doesn't have to check whether there is money in the bank first. It knows that legally its own Bank of England must pay when told to do so. It cannot refuse. The law says so.

As ever, politicians, economists and others like to claim that this is not the case. They pretend that the government is like us, and has to raise tax (which is its income) or borrow before it can spend. But that's not the case because the government has its own bank.

It's the fact that the government has its own bank that creates the national currency that proves that it is nothing like a household, and that all the stories that it is constrained by its ability to tax and borrow are simply untrue. The government is nothing like a household.

In fact, the government is the opposite of a household. A household has to get hold of money from income or borrowing before it can spend. But the gov't doesn't. Because it creates the money we use there would be no money for it to tax or borrow unless it made that money first.

So, to be able to tax the government has to spend the money that will be used to pay the tax into existence, or no one would have the means to pay their tax if it was only payable in government created money, as is the case.

That means the government literally can't tax before it spends. It has to spend first. Which is why that Act of 1866 exists. The government knows spending always comes before tax, so it had to make it illegal for the Bank of England to ever refuse its demand that payment be made.

So why tax? At one time it was to get gold back. Kings didn't want to give it away forever. But since gold is no longer the issue the explanation is different. Now the main reason to tax is to control inflation which would increase if the government kept spending without limit.

There is another reason to tax. That is that if people have to pay a large part of their incomes in tax using the currency the government creates then they have little choice but use that currency for all their dealing. That gives the government effective control of the economy.

Tax also does something else. By reducing what we can spend it restricts the size of the private sector economy to guarantee that the resources that we need for the collective good that the public sector delivers are available. Tax makes space for things like education.

And there is one other reason for tax. Because the government promises to accept its own money back in payment of tax - which overall is the biggest single bill most of us have - money has value.

It's that promise to accept its own money back as tax payment that makes the government's promise to pay within an economy rock solid. No one can deliver a better promise to pay than that in the UK. So we use government created money.

So, what has all this got to do with the national debt? Well, quite a lot, to be candid. I have not taken you on a wild goose chase to avoid the issue of the national debt. I've tried to explain government made money so that you can understand the national debt.

What I hope I have shown so far is that the government has to spend to create the money that we need to keep the economy going, which it does every day, day in and day out through its spending on the NHS, education, benefits, pensions, defence and so on.

And then it has to tax to bring that money that it's created back under its control to manage inflation and the economy, and to give money its value. But, by definition it can't tax all the money it creates back. If it did then there would be no money left in the economy.

So, as a matter of fact a government like that of the UK that has its own currency and central bank has to run a deficit. It's the only way it can keep the money supply going. Which is why almost all governments do run deficits in the modern era.

And please don't quote Germany to me as an exception to this because it, of course, has not got its own currency. It uses the euro, and the eurozone as a whole runs a deficit, meaning that the rule still holds.

So deficits are not something to worry about, unless that is you really do not want the UK to have the money supply that keeps the economy going, and I suspect you'd rather we did have government money instead of some dodgy alternative.

But what of the debt, which is basically the cumulative total of the deficits that the government runs? That debt has been growing since 1694, almost continuously, and pretty dramatically so over the last decade or so, when it has more than doubled. Is that an issue?

The answer is that it is not. This debt is just money that the government has created that it has decided not to tax back because it is still of use in the economy. That is all that the national debt is.

Think of the national debt this way: it's just the future taxable income of the government that it has decided not to claim, as yet. But it could, whenever it wants.

That's one of the weird things about this supposed national debt. When we're in debt we can't suddenly decide that we will cancel the debt by simply reclaiming the money that makes it up for our own use. But the government can do just that, whenever it wants.

This gives the clue as to another weird thing about this supposed national debt. It really isn't debt at all. Yes, you read that right. The national debt isn't debt at all.

That's because, as is apparent from the description I have given, the so-called national debt is just made up of money that the government has spent into the economy of our country that it has, for its own good reasons, decided to not to tax back as yet.

So, the national debt is just government created money. That is all it is. But the truth is that the people of this country did not, back in 1694 when interest rates were much higher than they are now, like holding this government created money on which no interest was paid.

You have to remember something else about those who held this government created money in times of old (though not much has changed now). They were the rich. If you don't believe me go and read Jane Austen's ‘Pride and Prejudice' and note how much Bingley had in 4% government bonds.

And there was something about the rich, then and now. They get the ear of government. And so their protests about ending up with government money without interest being paid were heard. And so, money it might be, but from the outset the national debt had interest paid on it.

The so-called national debt still has interest paid on it. But then so do bank deposit accounts. And they look pretty much like money too. Only, they're not as secure (at least without a government guarantee in place) and so the government can pay less.

But let's be clear what this means. The national debt is money that represents the savings of those rich or fortunate enough to have such things on which interest is paid by the government because it's been persuaded to make that payment.

Let me also be clear about something else. Those savings are not in a very real sense voluntary. If the government decides to run a deficit - and that is what it does do - then someone else has to save. This is not by chance it is an absolute accounting fact.

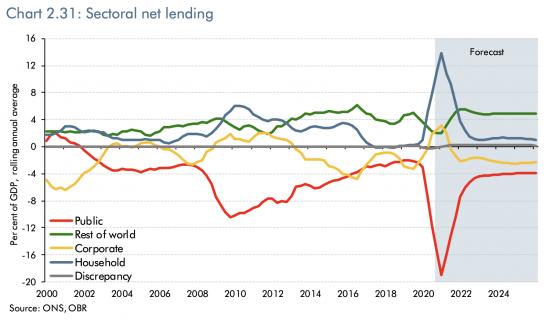

Where money is concerned for every deficit someone has to be in surplus. To be geeky for a moment, this is an issue determined by what are called the sectoral balances. There's a government created chart on these here.

The chart makes it clear that when the government runs a big deficit - as it did, for example, in 2009 - then someone simply has to save. They have no choice. And what they save is government created money. Which is exactly what is also happening now.

A growing deficit is always matched by savings. So who is saving? I am deliberately using approximate numbers, because they can quite literally change by the day. But let's start by noting that the most common figure for government debt was £2,100 billion in December 2020.

Of this sum, according to the government, £1,880 billion was government bonds, £207 billion was national savings accounts and the rest a hotch-potch of all sorts of offsetting numbers, like local authority borrowing. I don't think they do their sums right, but let's start there.

Except, these official figures are wrong. Why? Because at the end of December the Bank of England had used what is called the quantitative easing process to buy back about £800 billion of the government's debt, with that figure scheduled to rise still further in 2021.

I don't want to explain QE in detail here, because I have already done that in another thread, that I posted as a blog here. https://www.taxresearch.org.uk/Blog/2020/11/22/the-history-and-significance-of-qe-in-the-uk/

So let's, taking QE into account, discuss what really makes up the national debt, starting with an acknowledgment that if the government owns around £800bn of its own bonds they cannot be part of the national debt because they are literally not owed to anyone.

Around £200 billion of the national debt is made up of National Savings & Investments accounts. That's things like Premium Bonds, and the style of really safe savings accounts older people tend to appreciate.

Around £400 billion of the national debt is owned by foreign governments, which is good news. They do that because they want to hold sterling - our currency. And that's because that helps them trade with the UK, which is massively to our advantage.

But what's also the case is that that because of QE UK banks and building societies have around £800bn on deposit account with the Bank of England right now. This is important though: this is the government provided money stops them failing in the event of a financial crisis.

And then there's very roughly £700 billion of other debt if the Office for National Statistics have got their numbers right (which I doubt: they overstate this). Whatever the right figure, this debt is owned by UK pension funds, life assurance companies and others who want really secure savings.

Why do pension funds and life assurance companies want government debt? Because it's always guaranteed to pay out. So it provides stability to back their promise to pay out to their customers, whether pensioners, or life assurance customers, or whoever.

So now I have explained how we get a national debt and that it's a choice to have one made by government. I've also explained that all it represents is the savings of people. And I've explained the government could claim it back whenever it wants. And I've covered QE.

So, the question is in that case, which bit of the national debt is so worrying? Do we not want people to save? Or, would we rather that they had riskier savings that our pensions at risk? Is that the reason why we want to repay the national debt?

Or do we want to stop foreign governments holding sterling to assist their trade, and ours?

Alternatively, do we want to take the government created money back out of the banking system when it's saved it from collapse twice now (2009 and 2020) and which provides it with the stability that it needs to prevent a banking crash?

Or is it the national debt paranoia really some weird dislike of Premium Bonds that suggests that they are going to bring the UK economy down?

The point is, once you understand the national debt it's really not threatening at all. And what you begin to wonder is why so many people obsess about it. To which question there are three possible answers.

The first is that the obsessive do not understand the national debt. The second is that they do understand it, but want to make sure you don't. And the third is that they realise that if you did understand the national debt there would be no reason for austerity.

Of these the last is by far the most likely. There's always been a conspiracy to not tell the truth about money, and how easily it's made. There's also a conspiracy to not tell the truth about the fact government spending has to come before taxation, and the law guarantees it.

And I strongly suggest that the hullabaloo about the national debt - which is a great thing that there is absolutely no need to repay and which is really cheap to run - is all a conspiracy too.

The truth is that the national debt is our money supply. It keeps the economy of our country going. It keeps our banks stable. And it also represents the safest form of savings, which people want to buy.

There is no debt crisis. Nor is the national debt a burden on our grandchildren. Instead, the lucky ones might inherit a part of it.

But some politicians do not want you to know that there is no real constraint on you having the government and the public services you want. What the government's ability to make money, sensibly used, proves is we do not need austerity. And we never did.

Instead, the opportunity we want is available. And we do not need the private sector to deliver it. The government can and should take part in that process as well, which it can do using the money it can create as the capital it needs to do so.

But in order to pursue their own private gains and profits some would rather that this is not known, so they promote the idea that money is in short supply and that the national debt is a danger. Neither is true. We need to leave those myths behind. Our future depends on doing so.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

There are links to this blog's glossary in the above post that explain technical terms used in it. Follow them for more explanations.

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

Buy me a coffee!

Buy me a coffee!

As I always say, it is a good idea to regularly issue a rebuttal to the lies we are told about money creation/making and the relation to the concept of the ‘national debt’.

If one accepts the prime role of central banks and governments, then under the rubric of the deficit hawks all that saving would swallow up that money and our economy would be left with what exactly to pay wages and bills etc,?

So money as a utility has to be supplied into the economy by the state just to make things work.

Oh wait – but that’s what fiscal anarchists want isn’t it – the sole right to lend THEIR money with interest I suppose. They’d fill the gap – how nice of them.

Here’s a recent post from Stephanie Kelton – her name might ring a bell, highlighting the creeping fiscal hawkism in the U.S. too if it helps.

https://stephaniekelton.substack.com/p/it-turns-out-that-no-one-wants-to?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email

“Do Taxes and Bonds Finance Government Spending” is now behind a pay wall but “Can Taxes and Bonds Finance Government Spending” is available for free from the Levy Institute:-

https://www.levyinstitute.org/pubs/wp244.pdf

It bugs me that we’re sometimes told how much of the National Debt we each owe. What is not mentioned is that less than 0.15% is due to individuals, the remaining 99.85% is corporate debt. It does not look very equitable.

Sources

2021 Bank of England https://tinyurl.com/4mfh8fns

2022 MoneyNerd https://tinyurl.com/345befaw

I think you are getting your debts confused

Somewhere, somehow in the last 52 years the government found ways to spend money on services that delivered a multiplier less than 1. That’s the only way I can explain why the recorded value of the ‘national debt’ keeps increasing.

Technically the multiplier of government could be just over 1 and an inefficient tax system brings it below 1.

No, the national debt incrteases beacuse the size of the economy does and that requires an increased money supply

It is as easy as that

Don’t look for hard explanations when easy ones work and in the case of money are invariably riught

“It’s pretty obvious that as we create more and more of these REAL goods and services, we’re going to need more and more dollars in our money-lake—otherwise, one of two things will occur: (a) the dollar value of everything we own will begin to fall precipitously (deflation) because the same number of dollars has to be allocated to more and more stuff; or (b) we’ll have to begin producing FEWER real goods and services to keep prices aligned with the amount of money in the lake. This is called “shooting yourself in the foot,” although it would be more accurate to infer the aim is directed considerably higher.”

https://neweconomicperspectives.org/2013/02/real-dollars-and-funny-money.html#more-4882

Agreed

Hence the need for more money

second para should it be ‘NO such thing as a National Debt?’

I have always though of money as a credit rather than a debt. With it I can demand goods and services. But I assume it is the other way of describing it.

And money, even in conventional terms, is not wealth. In Robinson Crusoe he finds another wreck and in the Captain’s cabin discovers a bag of gold coins. He throws it down in anger as there is nothing to buy with it. As you often point out , the limits of money is the availability of resources.

This is a great description of the ‘National Debt’ and will be sharing it.

PS I actually voted for Molly Scott Cato in the Euro elections and she got in. The only other one I have voted for in the last 20 years who was actually elected was Bill Revans my local Councillor and now leader of the Somerset Council.

You are right re the second para

The dramatic Alison Rose resignation in the backdraught from the Farage banking debacle brings up permutations of implications for banking. I wish to select one single issue I feel is overlooked, but in some ways the most critical. The issue (complicated and oversimplified in the media) appears to be about access to banking; but is potentially even more basic: our access to money.

As you argue in the piece about the national debt above: “notes and coin are only a very small part of the money supply – a few percent at most. The rest of the money that we use is made up of bank balances.”.

Economists have always been intellectually sloppy about the implications of their over casual segmentation of money (M0-M4 etc) as if all that mattered was the maths of circulation, rather than the existential characteristics of the forms they take. The problem is that, although bank balances seem like money as robust as notes and coin, they simply aren’t. The proof of that is the guarantee supplied by the Government of all balances held in High Street banks of up to £85,000. Banks can fail; and as we all know too well, have failed (we are still living with the consequences: the Government still owns 39% of NatWest). There is a hierarchy of money (Mehrling), and High Street Banks do not hold your money (the top of the hierarchy); they turn your money into deposit credit (not the top of the hierarchy, just credit, just a commercial IOU – hence the Government guarantee).

We are moving toward the digital age in money transactions, and Government and commercial banks are trying to push people away from cash (notes and coin, money that is guaranteed 100% by Government) into what is in reality ‘second-string money’, in the form of commercial banking credit (only covered by specific guarantees). We are therefore effectively de-monetising society; reducing ordinary people’s access to the most risk free form of money, for market economy credit. Only the banks themselves will have direct access to money, once the de-monetising digital banking revolution is complete. As independent commercial entities banks may refuse credit. It is unavoidable. This is very different from the free circulation of money (notes and coin). Turning money into credit, it is easily fogotten, is a form of central control.

The High Street banking system has failed civil society. Commercial High Street banking requires root and branch, fundamental reform. I doubt traditional, independent profit/bonus driven joint stock companies are capable of doing the fundamentally critical job of freely circulating money to all in the digital age.

I think you are right…

Ive always thought ” money is debt “only tells half the story

yes — its debt because we owe the Govt.as it has invested on resources on our behalf

no —- because double-entry implies that weve received the benefits of these resources

@Rob Gray: “I’ve always thought ” money is debt “only tells half the story

Indeed. As a teacher, when I get paid by the government, I owe them nothing, I have earnt my salary. Likewise, when the government builds a road, or spends anything into the economy, it is literally “quid pro quo”, and the government wants for nothing.

Government debt — misleading

Government deficit — misleading

Government investment — more accurate?

If anyone were foolish enough to complain to me about Public Debt, I would simply reply – Private Debt.

Private Debt is far greater than Public Debt and is far less monitored. It is created by banks “printing money” to make loans. The money is cancelled by repayment of the loan, but the bank also charges interesst, part of which is insurance against the loan going bad. The poorer you are, the higher the insrance, the equivalent of a perfectly regressive tax. Who “prints” the money that pays that insurance? Where is the outcry that private debt is unaffordable?

I slightly disagree with Richard on tax. I suggest that in a working economy, the main function of tax is to redistribute money. And as far as I can see, tax is the only effective process stemming the trickle-up of money from the poor to the rich. So that a policy of reducing taxes is a policy to increase inequality.

Final question: If Private Debt is insured with government-backed money, where is the insurance premium that the government should receive for providing that cover/

I think you miss the fact that I argue that there are six reaasons to charge tax:

1) To ratify the value of the currency: this means that by demanding payment of tax in the currency it has to be used for transactions in a jurisdiction;

2) To reclaim the money the government has spent into the economy in fulfilment of its democratic mandate;

3) To redistribute income and wealth;

4) To reprice goods and services;

5) To raise democratic representation – people who pay tax vote;

6) To reorganise the economy i.e. fiscal policy.

Great explanation, thanks Richard. I think the thread skirts the importance of the cost of servicing the ‘national debt’ in peoples’ minds.

Bonds are liable to interest payments, which have become expensive in recent times. The Government/Treasury issues new bonds based on the current price of debt as I understand it, the yields that the market decides. These yields are affected by various factors, economic and political.

So if the size of the national debt isn’t in itself an issue, then the current and possible future interest payments can be worrisome – as higher interest payments on a larger national debt means a greater deficit, meaning either greater borrowing at high rates or austerity to ‘balance the books’, at least as the current economic paradigm dictates.

It’s the balancing of the books aspect that feels ridiculous now to me, with this (hopefully) greater understanding. We just don’t need to do so.

‘Borrowing’ via bonds only temporarily takes money out of the economy and from whom it is taken is transitory as they are bought and sold freely. So do bonds even affect inflation at all? If not, then balancing the books is an entirely arbitrary exercise and is presumably to provide some kind of appearance of competence with ‘managing the nation’s finances’.

In which case interest payments and therefore austerity becomes an entirely political choice.

I assume to be corrected if I’ve got any of this wrong?

Please r3ead my post yesterday on the paper from James Galbraith.

Markets do not set interest rates – including on government debt. US regulators set the scene and regulators here finsesse things, but there is no market in interest rates.

So, high interest rates are solely by govermment choice right now.

In that case why worry about interest rates? Shouldn’t the worry really be about those who want to set them to favour the best off?

That raises an issue I don’t understand. Over the couple of years I have followed this blog I feel I have picked up a moderate understanding of the way money works (MMT) but that is all based on discussion of a single currency-issuing economy. What happens when several currency issuing economies interact? Could a relatively small economy like Britain’s choose a significantly different approach from its bigger neighbours (USA and Eurozone) on interest rates for example without the disparity having its own effect on the economy? Would it effect things like trade volumes and inward or outward investment to the extent that the different economic approach might be undermined?

I apologise if this is the sort of question that goes beyond what can be addressed by comments.

Anyway, my thanks for this post, every time you give one of your long explanations like this another lightbulb comes on in my brain.

Jonathan

Apologies. Sometimes a comment goes astray here. Yours clearly has.

The answer is that there would be a shift in exchange rates, maybe. I stress the maybe.

The impact would be very much smaller than Brexit.

“Shouldn’t the worry really be about those who want to set them to favour the best off?”

Absolutely but as you rightly also say we need to compensate savers for inflation. The amount of savings though needs to be capped with the exception of the pension industry but again with some capping to avoid pensions being exploited better the best off.

I am not sure gow you suggest savings should be capped

Ian

If it helps – even if I am wrong – here’s how I see ‘the deficit’ which to me is just a record of what the government has spent into the economy or holds for others. Money (the pound) is owned by the government on a legal basis, it is creature of government policy.

For me, one’s own currency is the purest, most powerful and perhaps the only form of sovereignty worth having and should never be relinquished to anyone including the private sector banks in your country. Try telling that to a BREXITEER.

It is or SHOULD be investment – sure – in housing or our infrastructure – mostly these days under invested in I would say ,the moan being that government investment crowds out private ‘investment’ which is all to often just rentierism anyway.

Government money is printed as a utility into the economy to make goods and services transferable between people – including those who may not have the means to do this themselves (benefits, pensions) because it works out just as expensive for society if you do not.

The government can also hold people’s money for them too – this is often also portrayed as debt which makes me particularly angry as all it is, is money voluntarily held with the safest bank – the country’s central bank. A government can sometimes use bond issuance to attract extra money hanging about in the economy and temporarily take it out of circulation as a means to control inflation.

Only a government can afford to go to war on a huge scale, since it can print money to finance that – the only limit being the nation’s ability to provide materiel. Thinking about war actually is a good place to start when thinking about government spending. If only other areas of national life were so automatically guaranteed the money needed? Telling, eh?

It terms of managing the money supply, this is where the truth of tax is revealed (lots of lies here) – tax is the safety valve that ensures that as money is made and used, it is also destroyed to help curb inflation (from a build up of too much money). As it is government money, government can even reuse tax if it wants.

And then we have the private sector and their ability to print money with permission by the government. Their money is usually distributed as interest bearing credit which is also culpable for causing price bubbles.

The ongoing story is about the narrative of state/government spending versus private (credit under license or hoarded money being used as credit).

To me, its a constant war and a dirty one where lying is dominant. One thing I think we can both agree upon though is that the word ‘deficit’ is totally inappropriate as a word to describe how things really work.

The other thing I can say is that since the pound has been created, it was done so in the context of pluralism – with the Bank of England sharing the dynamics of its legal tender with private individuals and markets. Because it made complete sense.

That’s more than what can be said for anti-pluralists like the Neo-liberals and other fascists/greedy bastards who want government out of it, and to be in charge of the money supply for themselves. Because they’re worth it, apparently.

Sovereign Money is a nation-making project Ian – not a private sector one. That’s the truth. Sovereign money was the making of markets, and which actually made this tiny little country so great and also so terrible.

And those people it made – the rich – are quite frankly out of control in my view.

As I said, just my take on it – but read Christine Desan’s ‘Making Money: Coin, Currency and the Coming of Capitalism’ (2015).

One of the key light bulb moments in my grasping of MMT was the sectoral balances chart. They very simply and clearly demonstrate two key MMT points. Firstly, it all nets to zero. Secondly (and following) if we simplify to the three key sectors of government, domestic private sector and foreign sector then at least one of the three MUST be in deficit at any one time in order for the others to be in surplus.

So outwith a trade surplus (hello Germany!) the only way for a government to run a surplus and thus reduce the national debt is for the domestic private sector to be in deficit (ie for firms and individuals to run down their savings). Which, inter alia, appears the case now if we separate out banking: the current high tax (for the little people), high interest rate and high trade deficit can only be sustained by us little people running down our savings/ taking on more debt the only outcome of which will be the mother of all crashes without an unlikely change of course by the Austerity fetishists in both Tory and especially Labour parties

You’ve got it

Thank you for the clear and thorough explanation. The only thing that confuses me is the idea that the national debt did not exist prior to 1971. e.g. https://www.economicshelp.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/uk-national-debt-since-1727-lines.png shows a continuous line through this period and borrowing throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. What was the relationship between government borrowing and the gold standard?

Sorry if I gave that impression

It began nin 1694

The nature of the ‘debt’ changed in 1971 whyen the gold standard ceased to be relevant and the world only used fiat currency

That is the relevance of that date

Richard,

Thank you, this all makes complete sense, though I do have one question that perplexes me. Why did the Labour government of 1976 have to apply to the IMF for a loan, when they could have just created more money, or am I misunderstanding?

Thanks

Steve

They didn’t, but no one realised that at the time

Thanks, this narrative has been used as a stick to beat anyone who thinks differently and wants to challenge austerity ever since.

Cabinet papers reveal that in July the British cabinet had already made the decision to cut expenditure prior to negotiations with the IMF. The cabinet didn’t want to increase money supply in fear of criticism from the IMF, especially when the French and German governments were talking about deficit reduction. The cabinet also didn’t want to ‘balance the budget’ fully with expenditure cuts. They insisted upon a loan.

Here’s a table from, I think, Prof. Steve Keen, showing how mainstream “Neoclassical” economics is wrong on literally everything about money:

Neoclassical Economics Real World

—————-—— Private sector —————-—-

Banks Intermediaries only Money creators

Reserves Essential role in lending Irrelevant to lending

Debt Irrelevant to economics Critical to economics

Money No role in Economics Economics is fundamentally monetary

Credit No role in Macroeconomics Most volatile part of aggregate demand

———————— Government ———————-

Government Disturbs market system Creates market system

Debt Owed to private sector Created for private sector

Deficit Undesirable in long run Essential in long run

Surplus Prudent during booms Encourages speculative booms

Formatting went whoopsie, sorry!

Fascinating thank you. However, what this hasn’t covered is the availability of the resources we all need in order to survive. Food, fuel, clothing and shelter. Surely the ultimate measure of the economy is how easily available these things are.

I assume that these things are acquired via both human labour and the acquisition/exploitation/destruction of non renewable resources.

I would find your take on how that all works invaluable.

Youy could read my book The Courageous State….

Interesting that you (correctly) dare to use that much maligned word conspiracy to describe the politics of money in the UK.

I have long thought that if you want to conceal important genuine conspiracies the best way to do it is to flood the news media with bogus, simplistic, irrational conspiracy theories that pander to the worst aspects of the human psyche.

It is at least the partial reason why, while the world and this country in particular is going to hell in a handcart, the three biggest UK news stories this summer have been Philip Schofield, Huw Edwards and now Nigel Farage’s banking difficulties.

Keep up the good work Richard.

The current Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Scotland and Tory Peer, Malcolm Ian Offord, wrote in 2021:

“After a decade of austerity, where successive Conservative chancellors have parroted these same old lines, it’s time to slay some of these Tory dogmas and dispel the ingrained myths of post-war economics.

“Dogma number one: that government deficits are bad. By Newton’s third law, if the government is in deficit, someone else must be in surplus. So, who is the government’s counter party? Answer: we the people. So how can we the people being in surplus be a bad thing? Answer: only if the government spends its deficit on things which don’t benefit we the people. If it spends its deficit on good and worthwhile things that benefit us, like our health, our pensions, our defence, our economy, our education, our jobs, our housing and our environment, how can that be a bad thing?” — A sterling plan to save the Union, in The Spectator, 8 April 2021. https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/a-sterling-plan-to-save-the-union/

He also notes two further dogmas (interesting coming from a Tory financier):

* Dogma number two: that the state has no money

* Dogma number three: that government issuance of gilts is borrowing.

He got it

Agreed Offord got it, but it’s quite remarkable that he spoke truth to power at all and that he dd so in that most steadfastly Orthodox Tory magazine The Spectator. It also explains why I’ve never seen it before!

True

So seems to me that the narrative of the MSM that their is no money left because of the national debt is completely upside down.

Maybe the simplest way to challenge is that without the national debt there is no money.

Have I got that right?

You have

So do we need to stop the Bank of England destroying £80 billion a year for the next 10 years as part of their Quantitative Tightening programme? No wonder there is no money to deal with our polycrisis and permacrisis. They are very proud of themselves too.

Take this from the 19th July 2023:

https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/speech/2023/july/dave-ramsden-speech-on-quantitative-tightening-chaired-by-money-macro-and-finance-society

“First, when we decided on the initial £80 billion pace of unwind last September; we had no direct evidence on how sales would affect financial markets. The MPC incorporated this uncertainty into its initial decision on pace. From my perspective, I saw this as aiming under somewhat in order to incorporate a degree of ‘learning by doing’. The MPC has learned more about the economic and market impact of QT since then, with reassuring signs so far.”

The Bank of England is determined to blindly carry on.

Think about that: £80 billion a year. The cost of ending the 2 child cap on child benefit would, by contrast, be £1.4 billion a year.

It is terrifying.

Yes

See this morning’s post on this issue

This is a GLOBAL issue too. For example, this report on the European Central Bank’s Quantitative Tightening (QT) programme admits its largely being done for “legal and political reasons”: basically to eliminate the stigma of having created money through QE in the first place.

It then goes onto explore the risks of QT. Note here that as far as the central bankers, and the senior monetary experts who work with the central bankers often in “revolving door” type arrangements, are concerned the main risk of QT is causing another banking crash, and that’s true, that is a risk because running down the reserves of commercial banks at central banks does increase the risk of bank runs. Note, however, that the risk of strangling off government purchasing power at a time of polycrisis and permacrisis isn’t even touched upon.

Why is this? If dealing with the financial crisis and then the pandemic required governments to create money to cover their elevated spending (and it did) why does a global potential civilisation destroying climate emergency not have even greater implications?

There are two reasons why our central bankers and their top advisors are so staggeringly blind. Firstly we’re back to that stigma of money creation: central bankers don’t like to admit even to themselves that QE wasn’t just about monetary policy such as stopping deflation but also about supporting government spending, through clearly it was, as sometimes government debts were issued only in order to be immediately bought back with newly created money, and there would have been financial black holes across many wealthy nations hundred of billions deep otherwise. Secondly central banks don’t care about government spending, except in the limited situation when they’re asked by the government to raise more funds. Otherwise it is literally outside their ambit: it is someone else’s responsibility and problem. Then there is the additional factor that cuts in government spending, and general “austerity”, usually doesn’t affect senior central bankers and their mates: they tend to send their kids to private schools, have access to the best private healthcare and can still easily afford a place to live, possibly even inside a gated community with its own private security.

So, at a time when human civilisation faces its greatest existential crisis ever, we will globally cut our ability to respond publicly to that crisis, through governments that are meant to be our most powerful expression of our collective will, by literally trillions of dollars and dollar equivalents. We cripple our capacity for joint action at a time we need it the most. To call that decision CATASTROPHICALLY STUPID is an under-statement.

https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2023/741490/IPOL_STU(2023)741490_EN.pdf

Apologies, I may be having a bit of a meltdown (like the planet).