There is somewhat surprising analysis from Bloomberg out today that supports my hypothesis that interest rate rises are causing inflation, not curing it.

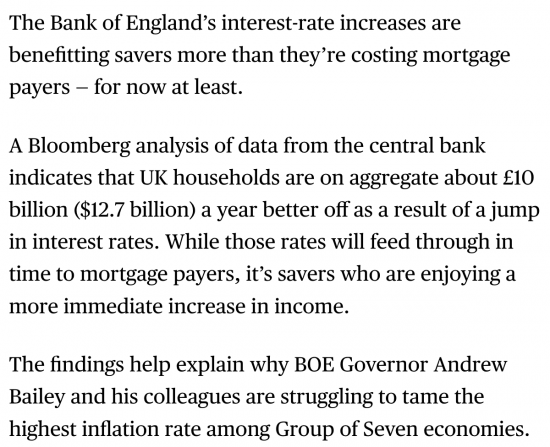

They explain this with a chart:

They add two important caveats, one implicit in this chart:

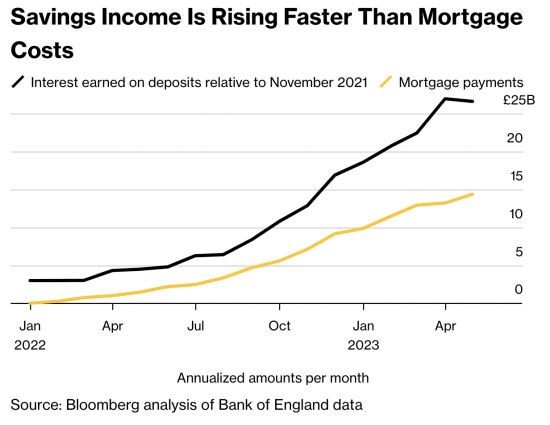

What is very clear is that the benefit of the increased savings held by those in the UK is skewed heavily towards the already well-off, which is aided by the fact that, unlike people in other countries, the UK population has by and large not spent the savings it made during the Covid era, as yet. They are now not only drawing those savings down but are boosting their spending because of the increased return on them, defeating the whole purpose of the interest rate rise.

The second caveat is that this trend might reverse as the number of fixed-rate mortgage deals come up for renewal. So far, relatively few out of the total have. Well over a million will do so in the next year, but by then savings rates might also have more generally risen as pressure on banks to do so rises.

Is the argument plausible? The data looks persuasive.

But in that case, what is causing the pressure on households? The answer would seem to be (and this is my speculation, not reflecting anything said by Bloomberg):

- Rent rises

- Utility bill rises, which despite capping have been substantial

- Food price increases

- Indexed linked cost increases, e.g. on mobile phones

- The cost of no mortgage borrowing

- The impact of profiteering, e.g. in fuel prices now.

Those all happen, I suggest, because the Bank of England has created the environment in which they continue to be possible. But as noted already, the impact is heavily skewed by the available disposable income of the person suffering these additional costs, which is heavily unevenly distributed in the UK.

I do not, then, think Bloomberg has a complete answer to what is happening. But what they have noted throws a massive spanner in the works of neoclassical economics thinking (which assumes near-instant policy transmission into practice, which clearly does not happen, as seen here) and so into the thinking of the Bank of England, who, as usual, have things wrong, even though the data used by Bloomberg came from them.

It really is time for a rate cut, and very soon.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

Funnily enough I remember back in the late 80’s when interest rates were much higher the electronics retailers were reporting a boom as pensioners came in to spend the interest on their savings on cameras, TV’s Video’s etc

If you have a ‘private’ pension as well the current hike in interest rates is no bad thing either

Apparently this letter was published in the Times. I cannot verify as its behind the paywall.

The Times published this letter recently:

“Sir,

I find it hard to believe that members of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee cannot see that hikes in interest rates are having zero effect on the global price of energy which has been feeding into the price of absolutely everything. Far from cooling domestic price increases, rate rises are adding to the cost of capital which is crucial to achieving growth an increased productivity which are so vitally needed. Not only that, but rates affect the availability and price of rental properties. Thus it can be argued that this inter-connected inflation also reinforces the demand for pay increases and the Bank has no sway over those demands, particularly in the public sector.

All Central Banks acted late and the UK has had its own problems but our Bank really needs to hold back and let price levels and the government bond market to find their own levels over the next few months. “

Well, today, my milkman based in Tideswell in the Derbyshire Dales told me that my doorstep milk deliveries are stopping because they cannot get the staff do it. Thus ends 23 years of supporting a local dairy.

Down the road from me at Rowlsey (there used to be a steam shed their Richard with an allocation of Jintys, Fowler 3F/ 4Fs and Horwich Crabs on the old Midland Mainline Derby – Manchester route via Buxton) Cauldwell’s Mill has stopped trading and working.

It was a listed Grade 2 working flour mill with a mill race and and internal mill wheel that had become a working museum. It no longer made flour but was a fascinating place to see how it used to be done. You could buy flour there (imported from abroad or elsewhere in the UK). There was also a vegetarian restaurant with the best Homity Pie in Derbyshire and home made cakes that provide decently paid jobs for youngsters. There was also a gift shop. It’s all closed, there’s been an auction and now what? There are still some arts and crafts shops open but its as dead as Dodo now. And the mill race is drying up and a habitat loss for birds seems to be in the making.

We spent hours there with our kids when they were younger, feeding ducks along the mill race, watching herons in the field nearby and dippers, swans, geese, ducks and swifts/sand martins cruising for insects and looking up at Minninglow Hill beyond and eating cake. It was so popular – always busy year round. And now its gone – we heard that they could not afford the insurance premiums. It might never reopen again. For 23 years we’ve bought our flour from there and made out own bread and its gone. All I can think of is the people whom we knew worked there. It must be awful.

I wonder how often this picture is repeated up and down the country – one that cannot manage the economy for everyone’s benefit?

Pathetic but also disastrous and tragic right at the same time as the rich are getting richer.

I know of that shed’s history.

What you are seeing is the inevitable social cost of crushing available discretionary spending out of disposable income.

As you say, it will at the very least take a very long time to recover.

Oh no! That was a favourite meeting spot for me (Hull) and my close friend (Coventry) for the last 20 years. Can’t believe it’s gone. And as you say, the impact on people is awful. Such a shame.

I sent this letter to the Today programme. Am I correct Richard?

‘The Health Secretary and Rishi Sunak repeatedly claim that the government cannot afford the £4bn pay claim of NHS health workers. Yet just months ago the government had no trouble affording an unfunded £48bn (sic) tax giveaway until the markets – not the Treasury – obliged them to think again.

And then again, the crippling mortgage interest rises are said to be essential to fight inflation yet thirteen rises have seen no reduction in inflation. As many economists have pointed out this is because current inflation is not due to excess money in the economy – which interest rate rises can indeed influence – but increased commodity prices, together with, wait for it, increased interest rates!

Why don’t BBC presenters challenge ministers on these issues?’

See a thread to come shortly

I’m not sure if this has come up in your timeline or if it’s worth you addressing, but Hugo Rifkind has come to similar conclusions to you despite, according to him, not having any expertise in economics. He notes there isn’t too much money chasing too few goods and so putting up interest rates will lead to increased debt costs for companies and increased rent costs for both the public and companies, leading to more inflation. So why is the BoE putting up rates, he asks?

https://twitter.com/hugorifkind/status/1676324552094232578

Former Bank of England employee Tony Yates answers that inflation is always caused by too much money chasing too few goods, and so despite inflation being caused by the supply chain issues from energy, Brexit, and Covid, the cure is still using monetary policy to bring down demand because there is no clear fix to many of the supply issues and monetary policy can be implemented faster than supply chain fixes. He doesn’t really address the point you and Rifkind are making about higher interest rates leading to higher prices, other than saying “we know from empirical work” that the increased costs to businesses from higher rates that you talk about are offset by other costs, without elaborating on this. In regards to your reference to the Bloomberg story, he says we know from “dozens of studies” that savers are less likely to spend the increased money from higher rates – although surely “less likely to spend” doesn’t mean there is zero increase in spend, and so how much is this increased spend?

https://twitter.com/t0nyyates/status/1676468465714987008

Even if Yates is correct and the inflation was caused by too much money chasing too few goods, he doesn’t address how interest rates affect both sides of this: as well as affecting the money supply, wouldn’t higher rates put a dampener on the economy, thus reducing the amount of “goods” produced, and so lead to money chasing even fewer goods, leading to more inflation?

Hugo Rifkind is right

In contrast I have rarely found Tony Yates to be right on almost anything. He is a deeply, even desperately, orthodox man always keen to toe the establishment line