The problems with Warren Mosler's description of modern monetary theory (MMT)

Richard Murphy[1]

April 2023

Published by Tax Research LLP[2]

Purpose of this note

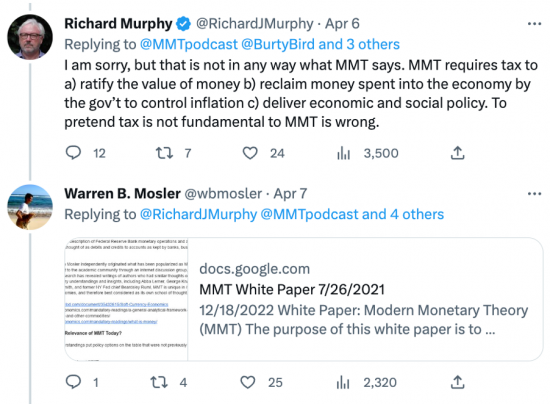

This note reviews a note published by Warren Mosler on Twitter on 7 April 2023 in response to a comment from Richard Murphy.

TLDR (Too long: didn't read)

On 7 April Warren Mosler posted a paper on Twitter which he claimed presented the fundamentals of MMT. I disagreed with him on that issue on Twitter at that time and was challenged to provide a response.

In this note I argue that:

- Mosler did not present a coherent argument as to what MMT might be in his paper.

- He did, in my opinion, present an argument suggesting that a jurisdiction without a government might be better off than one with a government operating MMT.

- Mosler's description of an economy fails to take into account the existence of commercial banks and their capacity to create money.

- Mosler incorrectly represents that the primary purpose of taxation is to create unemployment when this is not the case.

- To do so he and Bill Mitchell also appear to argue that MMT requires that a government tax before it spends and that tax revenues must equate to spending, both of which claims contradict usual understandings of MMT.

- Mosler also, in my opinion, misrepresents the cause of inflation by suggesting that it is always created by government action.

- The argument Mosler makes for a job guarantee are consequently based on what I think to be false premises.

An alternative view of MMT that does not rely on these arguments is presented.

A PDF version of this post is available here.

A PDF of the paper from Warren Mosler to which I am replying is here.

The exchange that led to this note being written

The exchange was as follows:

Mosler's claims on the nature of MMT

Mosler says in the introduction to his note, originally published on 7/26/2021 but apparently republished on 12/18/2022, that:

The purpose of this white paper is to publicly present the fundamentals of MMT.

I take that to mean that this is the definitive statement of his views. It is certainly presented as such in the note, where he says:

In 1992 Warren Mosler independently originated what has been popularized as MMT. In 1996 he introduced it to the academic community through an internet discussion group, and while subsequent research has revealed writings of authors who had similar thoughts on some of MMT's monetary understandings and insights, including Abba Lerner, George Knapp, Mitchell Innes, Adam Smith, and former NY Fed chief Beardsley Ruml.

Mosler portrays his own role in MMT as pivotal.

Mosler's view of MMT appears to be summarised in this statement:

MMT is unique in its analysis of monetary economies, and therefore best considered as its own school of thought.

It is in that case unfortunate that it is hard to find out precisely what Mosler means from reading this paper.

For example, under the heading *What is MMT? he says:

MMT began as a description of Federal Reserve Bank monetary operations and accounting, which are best thought of as debits and credits to accounts as kept by banks, businesses, and individuals.

No further explanation is supplied. The reader is left wondering what Mosler is referring to as a result, even if they are aware of the significance of double entry accounting in banking and the money creation process, which few people are.

Mosler's next heading is *What is the Relevance of MMT Today? In response he says:

The MMT understandings put policy options on the table that were not previously considered viable.

Again, no further explanation is supplied, which once again leaves the question he has posed unanswered.

Instead Mosler moves on to suggest that *What's different about MMT. He is slightly more fulsome in response, saying:

SEQUENCE:

MMT alone recognizes that the US Government and its agents are the sole supplier of that which it demands for payment of taxes

That is, the currency itself is a simple public monopoly.

The US government levies taxes payable in US dollars.

The US dollars to pay those taxes or purchase US Treasury securities can only originate from

the US government and its agents. [Formatting from the original]

The economy has to sell goods, services or assets to the US government (or borrow from the US government, which is functionally a financial asset sale) or it will not be able to pay its taxes or purchase US Treasury securities.

This, it is stressed, is the first comment of substance Mosler makes with regard to MMT. The message appears to be, in my opinion, that:

- MMT is an issue that is only of concern in the USA. That is not true. MMT has a much broader and potentially universal application.

- Government is a malign force, demanding payment of tax in a currency that only it creates. This is not true. In reality the US government only demands payment of tax because it has already, mainly benignly, spent money into existence in the economy. The demand for payment is not, as a result, malign. In any case, this claim is wrong. The US government might create what are called base money dollars. But US commercial banks can and do also create dollars through their lending. As such tax is not only payable using the money created by the US government; it can also be paid using dollars created by the US commercial banking system, which dollars are indistinguishable in use from those created by the US government.

- The US economy does not have to sell services or assets to the US government to pay taxes. If they refused to buy those goods and services the government has to sell, as is their collective right within that economy, then the tax liability to the US government would not exist. The logic in the claim to the contrary by Mosler appears, in any case, to be confused. It necessarily assumes that the obligation to tax precedes expenditure by the US government, when the whole point of MMT is to explain that this is not the case. It also assumes that the US government has the power in aggregate to impose tax when there is no justification, or the means, to do so. This is, again not true. US democracy has, to date, ensured that this does not happen. The claim would appear to be wrong in that case.

Mosler then claims that there are Ramifications of his claims on the nature of MMT the first of which he says is:

- The US government and its agents, from inception, necessarily spend (or lend) first, and only then can taxes be paid or US Treasury securities purchased.

This is in direct contrast with mainstream economic models and the rhetoric that states the US government must tax to get US dollars to spend, and what it doesn't tax it must borrow from the likes of China and leave the debt to our grandchildren.

MMT therefore recognizes that it's not the US government that needs to get dollars to spend, but instead, the driving force is that taxpayers need the US government's dollars to be able to pay taxes and purchase US Treasury securities.

The highlighted section is indisputably what MMT says, but I do not think that it follows from the claim that Mosler made in the preceding section, for reasons already noted. I think that there is a logical error in the flow of the argument here.

This is compounded by a further error. The statement Mosler makes that the US government does not need to get dollars to spend is true, because it can create them. But it does not follow that taxpayers need to take specific action to secure dollars to pay taxes. As a matter of fact, the dollars required to pay those taxes are already circulating in the US economy at the time that those taxes fall due for four reasons:

- They have been spent there before taxes fall due by the US government.

- The dollar is the only legal currency in the USA, meaning that it is the only currency used for other transactions, not involving the government. This is not the result of taxation law, but because of statute declaring the dollar to be legal tender.

- Because the dollar is the only legal tender in the USA that country's banks lend more of dollars into existence than the US government spends into existence.

- US taxpayers can make settlement of their tax liabilities using either US government created dollars or US bank created dollars, the two being inseparable in use.

In summary, because the US dollar is the legal tender of that country it is the only currency most US citizens will ever use, at least for their domestic transactions. Another practical option is not available to them. To suggest that dollars only exist for the payment of taxes or that there might be a shortage of them for this purpose does therefore, as a consequence, appear to be wrong. In fact, it is entirely plausible that US banks might loan dollars for this purpose, creating new currency as a consequence.

The implication within Mosler's statement that there is some difficulty in securing dollars to make tax payment does, therefore, appear to be wrong. The claim that follows from that assertion is, therefore, in my opinion also wrong.

The second ramification of Mosler's claim that the US Government and its agents are the sole supplier of that which it demands for payment of taxes is, apparently:

- Crowding out private spending or private borrowing, driving up interest rates, federal funding requirements and solvency issues are not applicable for a government that, like the US, from inception spends first, and then borrows. http://moslereconomics.com/mandatory-readings/a-general-analytical-framework-for-the-analysis-of-currencies-and-other-commodities/

No further explanation is supplied. The paper referred to is old, badly formatted so that the tables no longer work. Oddly, it also concludes that money is a commodity just like any other once imbued with value from taxation. If, however, this was the case we would not need to be discussing MMT because money would be of no special interest: any commodity might in that case be used in exchange. Nor would financial flows in dollars be of concern, let alone interest rates. I am sure that Mosler can see the link in his arguments: I admit that I cannot.

That is because I suggest that money is not like any other commodity. It may be that MMT says that “driving up interest rates, federal funding requirements and solvency issues are not applicable for a government that, like the US, from inception spends first, and then borrows” (saying which I make clear that I am not convinced about the claim on crowding out, for reasons already noted, above, and so have excluded it here) but that does at the very least require explanation, and Mosler does not provide one.

His claims on ‘How are you going to pay for it?' are as unhelpful. Here he says:

The US government, for all practical purposes, spends as follows:

After spending is authorized by Congress, the Treasury instructs the Federal Reserve Bank to credit the recipient's bank account (change the number to a higher number) on the Fed's books. <Note: The accounts of Fed member banks are called reserve accounts and balances in those accounts are called reserves.>

As far as I can tell (and I may be wrong here because of the ambiguity in what Mosler says) the only answer required to ‘how are you going to pay for it?' is, in Mosler's opinion, to say ‘by crediting people's bank accounts.' That is true: mechanically it is, in fact, indisputable. It also fails to answer just about any of the questions that anyone might ask of MMT. Double entry records transactions. It does not explain their causes or consequences. For that reason Mosler does not answer the question he poses.

The same problem is found in Mosler's next section, where he says:

How is the Public Debt Repaid?

When US Treasury securities mature, the Fed debits the securities accounts and credits the appropriate reserve accounts. Interest on the public debt accrues to the securities accounts and the Fed credits reserve accounts to pay that interest.

There are no taxpayers or grandchildren in sight when that happens.

Again, that is true: mechanically it is, in fact, indisputable. But once more this answer fails to answer the question that anyone might ask of MMT. Explaining double entry requires more than an explanation as to what the debits and credits are. Knowing them is useful, but they do have consequences and Mosler goes nowhere near explaining what those consequences are. I presume Mosler knows, although the possibility that he does not is left on the table. Most particularly, what he never says is that the government did not have to borrow in the first place since it already had a loan in place from its central bank. Missing that fact out makes this a wholly unsatisfactory answer.

Mosler's claim on taxation

Providing an unsatisfactory answer is, however, different from providing what I think to be a wrong one, which Mosler does next when it comes to taxation. On this he says:

THE CAUSE OF UNEMPLOYMENT:

MMT recognizes that taxation, by design, is the cause of unemployment, defined as people seeking paid work, presumably for the further purpose of the US Government hiring those that its tax liabilities caused to become unemployed.

That is it. This is what Mosler has to say on tax. Its purpose is to, apparently, create unemployment. The reason for doing so is to ensure that those made redundant might be employed by the government. I have only one description for this explanation, and that is that it is in my opinion wrong.

Mosler says no more on this issue. His statement is, in itself, apparently sufficient explanation on this issue. I have therefore investigated the origin of this claim which is, I think, to be found in Prof Bill Mitchell's thinking. He said[3] in 2016:

[O]ne of the activities of a currency-issuing government is to create idle real resources in the non-government sector there can be subsequently deployed by that government in pursuit of its electoral mandate.

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) shows that this is one of the major roles of taxation – to create unemployed real resources that can then be used by the public sector.

The public sector then deploys these resources through spending. We should note that the need to deprive the non-government sector of spending capacity via taxation is to ensure that total spending is commensurate with the available real resources in the economy.

He has also said[4]:

MMT shows that taxation functions to promote offers from private individuals to government of goods and services in return for the necessary funds to extinguish the tax liabilities.

So taxation is a way that the government can elicit resources from the non-government sector because the latter have to get $s to pay their tax bills. Where else can they get the $s unless the government spends them on goods and services provided by the non-government sector?

He repeats the claim here[5]:

Another way of seeing that is to understand that given that the non-government sector requires the government's fiat currency to pay its taxation liabilities, the imposition of a tax liability (without a concomitant injection of spending) by design creates unemployment (people seeking paid work) in the non-government sector.

I offer three versions of this narrative from Bill Mitchell just to make clear that I have not misinterpreted this claim: it is what Mitchell and Mosler are saying.

Each of these claims by Mitchell, and the one that Mosler makes based on them, has to be wrong if the essential claim that MMT makes, which is that government spending precedes taxation, is to be true.

Mosler and Mitchell contradict that claim by saying that unless taxation first of all forced resources in the private sector into unemployment then government spending to acquire those resources would not be possible. What they are necessarily saying as a result is that tax must precede spending. If it did not then, in their very clear opinion, there would be no resource for the state to acquire. Their claims do, in that case, appear to flatly contradict the observed fact that MMT exists to promote, and which Mosler claims is its unique proposition, which is that government spending precedes taxation.

As a matter of fact, logically Mosler and Mitchell's claims must, in my opinion, be wrong. The reality is that a state can, using money it has created, act as a purchaser in the market within a jurisdiction, just like anyone else. Just as other market participants secure the goods and services that they require by paying the going rate for them in currently prevailing market conditions, so too does the government. If the price that the government offers for whatever it seeks to buy is sufficient to attract sellers then those sellers voluntarily make a sale to the government, whether of goods or their labour. The state then taxes to withdraw the excess money supply it has created when making this purchase to control the resulting risk of inflation which would otherwise arise. If it gets the judgement on the amount of money to withdraw from the market right then there will be no resulting inflation and the combined market and state sectors will, together, deliver full employment.

This is what MMT actually seems to say when describing the operation of a government in a market economy. It describes how a government behaves in a mixed market-based economy. I cannot reconcile that with the Mosler and Mitchell view. That is because Mosler and Mitchell say something very different. As Mitchell noted in the first paragraph of his 2016 article, the assumption that they make is that if resources were not used by the state they would be used by the private sector. In other words, both he and Mosler appear to assume that there exists a parallel world in which all resources available within an economy in which there was no state are the same as those available when there is a state. In addition, they appear to assume that those resources could be utilised without the existence of the state and full employment would follow in its absence.

Extraordinarily, what this means is that they appear to assume that Say's Law applies. What Jean-Baptiste Say said in 1803 was that the production of a good creates the demand for it. He did, therefore, argue that markets will always ‘clear' i.e. they will create the demand for all the goods that can be supplied resulting in an optimal economic outcome. Mitchell and Mosler appear to assume that such a state exists and that functions as Say suggests it would, delivering economic equilibrium without government interference.

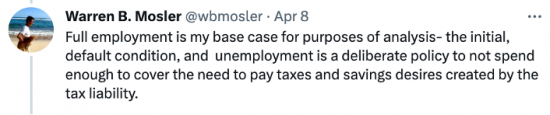

It would appear that this must be the case because of another claim made by Mosler. He says when discussing the job guarantee, later in his document, that:

Residual unemployment is caused by the government not hiring all of those that its tax liabilities have caused to become unemployed.

Mosler repeated this in slightly different form in Twitter exchanges with me on April 8, saying:

The implication could not be clearer: unemployment is in Mosler's view the deliberate creation of a government. The market – the creator of Mosler's default assumed state of full employment - does not create unemployment; it is the state that he says does so, and he says that it does so by choice.

The logical flow through this argument must be as follows, in my opinion:

a. Before the intervention of a government there is a market that is in equilibrium, i.e. it delivers full employment without state intervention.

b. That market leaves no spare resources unused.

c. If the state wishes to spend it does as a result have to tax to force resources in that market economy out of use.

d. How that tax is paid when there has been no government currency spent into existence is not clear: there must be an alternative currency in use, but that is not made clear.

e. The value of the tax charged is the value of the resources forced out of use.

f. If the government does not spend the amount it has taxed then not all those resources that it has made unemployed by imposing taxation will be put back into use.

g. Tax must then always equal the amount that the government spends if unemployment is to be avoided: balanced budgets are required by Mitchell and Mosler's thinking.

h. If the amount that the government does spend is less than the amount taxed then unemployment will result at the sole choice of the government.

The following are also implied:

i. The market clears by itself until there is government intervention.

j. That market can function without government currency.

k. The state creates imperfect markets.

l. One logical consequence of that imperfection is unemployment, which would not otherwise happen.

m. This unemployment results from the state not supplying sufficient money supply to the economy, in which it is the only creator of that currency, having forced the previously efficient market created currency out of use.

n. All economic imbalance is, therefore, the consequence of government intervention in the market.

It is obvious to what conclusions this thoughts lead, which I suggest are as follows:

o. The government should not intervene in the market.

p. The government should either not tax, or do so as little as possible.

q. The government should not seek to impose the use of its self-declared legal currency on the market because the economy behaved optimally without it.

It is exceptionally difficult for me to see what else the argument Mitchell and Mosler make implies.

To be candid, it would be hard to find an Austrian economist – which school of thought most despises government intervention in markets – who could come up with an argument quite as anti-government as this, and yet this argument is apparently at the core of MMT if my interpretation of what Mitchell and Mosler say is to be believed.

However, I think that Mosler and Mitchell are wrong for these reasons:

a. There is no parallel economy that exists in the form that Mosler and Mitchell assume.

b. No one has to force economic resources out of use in the economy so that they might buy them: instead, the usual rules of market exchange apply.

c. People work for the government and goods and services are sold to it voluntarily: except in those states where conscription still applies no one has to work for a government. To claim that offering such employment is the only way to solve unemployment created by taxation is simply not true.

d. Nor is it true to say that taxation is raised for the purposes of creating unemployment. This is never the case. There are six reasons to tax:

1) To ratify the value of the currency: this means that the payment of tax in the currency that a government has created provides that currency with a value in exchange in a jurisdiction;

2) To reclaim the money the government has spent into the economy in fulfilment of its democratic mandate in order to prevent inflation;

3) To redistribute income and wealth;

4) To reprice goods and services whether upward as in the case of carbon or downward as in the case of education and medical services;

5) To raise democratic representation because people who pay tax vote;

6) To reorganise the economy i.e. through the support tax supplies to fiscal, economic and social policy.

As is apparent, the creation of unemployment is not in that list.

e. There is no parallel currency which could be used in the absence of a government created currency.

f. Markets do not clear at full employment, whether with or without government intervention. The claim that this might happen was debunked by Lord Keynes and nothing since he wrote has suggested that he was wrong. Say's Law is wrong.

g. Governments are not the sole creator of money, although they are the sole creator of a currency and the sole curator of the value of that currency.

h. That means that tax need not only be paid using the currency injected by a government into an economy as a consequence of it spending: it can also be paid using money created by a commercial bank.

i. Governments do not deliberately create unemployment, although they can tolerate a level of unemployment created as a consequence of the inefficiencies found within any economy because of failures to communicate and consequent timing differences in required actions arising between the state and private sectors, both of which sectors can as a consequence contribute to the creation of that unemployment as a result of the inevitably imperfect actions of each of them.

j. There is no requirement that a government tax the amount that it has spent, as implied by Mosler and Mitchell. In fact the opposite is most likely to be true.

k. The likelihood that full employment will be the same with or without the action of a government is remote in the extreme. The evidence that government has a benign effect is to be found in data suggesting that those governments that are more effective in upholding the rule of law and which have better designed programmes of intervention in their market economies deliver overall higher levels of income for the people in the jurisdictions for which they are responsible than those governments that refrain from active engagement in their societies and economies for whatever reason. The implication of Mosler and Mitchell's reasoning, that governments should not intervene in their economies is, therefore, inappropriate.

l. As a matter of fact, governments do spend before they tax: the logic, implicit in Mosler and Mitchell's claims that government's tax first is, therefore, factually wrong and contrary to what they themselves say of MMT.

Having dealt with this issue and having demonstrated that the basis of the claims that Mosler has made in his paper on tax appear to be wrong, the other issues to which he refers within it can be dismissed fairly quickly.

Mosler's claims on inflation

On inflation, Mosler says:

INFLATION:

Only MMT recognizes the source of the price level: the currency itself is a public monopoly and monopolists are necessarily “price setters.”

Market forces determine relative prices. Their only information with regard to the absolute value of the currency comes from the state through its policies and institutional structure.

Therefore:

The price level is necessarily a function of prices paid by the government's agents when it spends, or collateral demanded when it lends.

Mosler argues that this is the case because:

In what's called a market economy, the government need only set only one price, as market forces continuously determine all other prices as expressions of relative value, as further influenced by institutional structure.

As with Mosler's arguments on taxation, this argument appears to have implicit within it Mosler's apparent belief that an economy would, without government, intervention act optimally, using resources to the best effect, at full employment, and with stable prices. In my opinion that argument is wrong.

Markets are entirely capable of creating inflationary pressure without any involvement of government, whether due to price speculation, excessive profit taking, the exploitation of monopoly power, deliberate disruption of supply chains, or imbalances of power within the marketplace, e.g. between monopsonist[6] employers and employees denied union representation. To ignore all these possibilities and to suggest that the only cause of inflationary pressure is the prices paid by the government when it spends pushes the boundaries of credibility beyond any reasonable limits, in my opinion. It does also, once again, imply that it is Mosler's belief that society would be better off without government. Very few of those who appear to support MMT seem to share that view.

Mosler on the Job Guarantee

Finally, Mosler turns to what MMT describes as the Job Guarantee. On this he says:

Residual unemployment is caused by the government not hiring all of those that its tax liabilities have caused to become unemployed. That is, it's a case of a monopolist- the government- restricting supply, which in this case refers to net government spending.

Current policy is to utilize unemployment as a counter-cyclical buffer stock to promote price stability. Another policy option is for the government to use an employed buffer stock, rather than an unemployed buffer stock, to promote price stability.

The Job Guarantee is a proposal for the US Government to use an employed buffer stock policy by funding a full time job for anyone willing and able to work at a fixed rate of pay. A $15 per hour wage has currently been proposed. This wage becomes the numeraire for the currency- the price set by the monopolist that defines the value of the currency while allowing other prices to express relative value as further influenced by the institutional structure.

The Job Guarantee works to promote price stability more effectively than the current policy of using unemployment, by better facilitating the transition from unemployment to private sector employment, as private employers don't like to hire the unemployed.

It also provides for a form of full employment, and at the same time is a means to introduce minimum compensation and benefits “from the bottom up,” as private sector employers compete for Job Guarantee workers.

There are good reasons to think that a government should proactively support employment through the provision of a job guarantee at a minimum wage. Those good reasons do not include those noted by Mosler because, for reasons, already noted, the underlying assumptions in his first two paragraphs appear in my opinion to be wrong and, as a consequence it has to be assumed that the other claims that follow are unsupported.

Summary

In his paper Mosler claimed to set out the fundamentals of MMT. My argument is that he failed to do so.

Those fundamentals are, in my opinion:

- That a government that has its own central bank and currency, which currency is internationally acceptable, need neither tax nor borrow before spending because its entire government expenditure can be funded by new money creation by its central bank acting on its behalf, with the government then being indebted to its central bank for the sum expended.

- A government that borrows in this way from its own central bank need never repay the debt it owes to its central bank because that debt represents the money supply of the jurisdiction for which it is responsible and that money supply must, therefore, be maintained if the level of economic activity in that jurisdiction is to be sustained.

- The primary role of taxation in the funding cycle of such a government is to control the inflation that might be caused by the excessive creation of new money by that government when fulfilling its expenditure plans.

- The secondary role of tax in the government's funding cycle is to provide the government created currency of a jurisdiction with value in exchange. That happens because if the tax owing to a government can only be settled using the currency that government creates those transacting in that economy who are likely to have tax liabilities arising as a result will not be able to afford the exchange risk arising from trading in any other currency.

- Once these roles of taxation have been fulfilled the additional role of taxation for a government is as a tool for the delivery of its economic, social, regulatory and inequality agendas. The design of taxes for this purpose is, however, never intended to have a revenue raising function to enable government expenditure to take place, that expenditure having already been funded by the central bank of the jurisdiction on the government's behalf.

- A government in the situation described need not balance its expenditure and taxation income. In most situations that balance would, in fact, be undesirable. If the government has a growing economy and modest, but controlled inflation within that economy, then the expansion of its money supply is essential, and that expansion of the money supply is best delivered by the running of government deficits. Such deficits represent a shortfall of tax receipts compared to government expenditure. This policy should be preferred to increasing the scale of private sector borrowing within the economy, which is the alternative source of new money creation.

- A government in the situation described need never borrow from financial markets. That is because the government can always borrow instead from its own central bank. It has no dependency on financial markets as a consequence.

- A government in the situation described may, however, wish to offer a savings banking facility to those in the jurisdiction for which it is responsible who wish to save in the currency that the government in question has created. It does so in its capacity as a borrower of last resort. This deposit taking does not represent government borrowing: it is a banking arrangement. Even if the funds deposited with the government are then used to clear the apparent overdraft advanced by the central bank to the government the status of these deposits as a third-party bank or savings facility is not changed: the central bank can always guarantee the repayment of the deposits in question by the creation of new money, which is precisely why the government is able to offer this borrower of last resort facility.

- A government in this position does not need to use interest rates to control inflation. It can instead use the following mechanisms to control:

- Varying tax rates over one or more taxes to tackle the cause of the inflation being suffered. New taxes may be required to assist this process.

- Varying the scale of the deficit.

- Credit controls to limit commercial bank lending.

- A government in this position would seek to run a low effective interest rate policy within its economy to firstly minimise interest obligations to those to whom it provides banking facilities; secondly to provide the best possible environment for investment by lowering the cost of capital; and thirdly to minimise the upward reallocation of resources within the society for which it is responsible as a result of interest paid, thereby reducing inequality, which goals in combination have the best chance of delivering overall economic prosperity.

- A government in this position can have a policy of full employment, knowing that until that point is reached, there will be under-used resources within that economy for which they are responsible, meaning that inflation will not be stimulated as a result so long as the resources put to use are those currently unemployed, whether they be people, physical assets, or intellectual property. This policy could include the provision of a job guarantee for all those seeking work within the economy who are unable to secure it, but any such policy must reflect the individual circumstances of the job seeker and be consistent with the overall delivery of social security within the jurisdiction for which the government is responsible, and cannot as such be a critical component within the economic policy of the government in question.

In contrast, Mosler appears to suggest that:

- Economies would be better off without governments.

- Governments act with malign intent to impose their wills on society.

- They do so by taxing before spending.

- Having imposed that taxation they then deliberately create unemployment by refusing to spend the revenues they raise, which he (along with Bill Mitchell) suggests must equal the tax raised if unemployment is to be avoided.

At the same time Mosler provides no explanation as to what MMT really is, how it might work, what the broader role of tax is within it (in the process most especially ignoring its role in controlling inflation, which phenomenon he incorrectly explains, in my opinion), whilst promoting a job guarantee on the basis of what I think to be false premises.

I am, of course, aware that there are others (most especially, but not only, Stephanie Kelton) who have made good these deficiencies and who have presented coherent and logical arguments for MMT, as I also think I do. As a result, I stress that in writing this note I am not suggesting that MMT is not credible. I believe that it is. What I am saying is that significant parts of the arguments promoted by Warren Mosler and Bill Mitchell appear to me to directly contradict many of MMT's commonly understood fundamental tenets. They also appear to promote arguments hostile to the existence and benevolence of government that would appear directly contrary to the views that many of MMT's advocates would appear to support.

[1] Richard Murphy is the director of Tax Research LLP, Professor of Accounting Practice, Sheffield University Management School, a chartered accountant and Fellow of the Academy of Social Sciences.

[2] Tax Research LLP, 33 Kingsley Walk, Ely, Cambridgeshire, CB6 3BZ. Registered at this address. Registered number OC316294

[3] https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=33152

[4] https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=7261

[5] https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=50005

[6] A monopsonist is a single buyer for a product or service of which there are many sellers.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

There are links to this blog's glossary in the above post that explain technical terms used in it. Follow them for more explanations.

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

Buy me a coffee!

Buy me a coffee!

“In 1992 Warren Mosler independently originated what has been popularized as MMT.”

Is this true or just some form of self-aggrandisment? He seems to be trying to claim ownership, however disjointed his “explanations” seem to be.

Who would you credit the origin or development of MMT to?

Not Mosler

And I also came to these understandings before realising they were described as MMT as I noted in a blog in 2013

I think it developed

The name was coined by Bill Mitchell, I think. It is not a good one.

Perhaps you should read Warren Mosler’s book “7 Deadly Innocent Frauds of Economic Policy” 7DIF https://www.moslereconomics.com/wp-content/powerpoints/7DIF.pdf

You can purchase the book if you want on Amazon if you like.

Warren Mosler describes where he originally learned MMT in the second half of the book.

The forward to the book is written by:

James K. Galbraith

The University of Texas at Austin

June 12, 2010

I have

This is a three pipe problem, Watson.

But having read Stephanie Kelton’s book last year, I think you and her are on the same page.

A fe years ago I think you said something along the lines of -that Mitchell, being a pioneer occupying new territory, can be very defensive and , possibly, dogmatic. I have seen him on youtube and came away having reservations about him. This is an important discussion which you are right to raise.

Thanks

I sense little common ground between Stephanie and Bill

I have not asked her about my current publications

I long ago gave up on Bill because he was far too abusive. I can be robust, but he is much worse

I cannot understand the Mosler I thought I knew with what I have checked out he is saying now – the two seem irreconcilable.

It’s as if when coming to the conclusion about the power of governments and their money that he has had a cold war panic attack and was then seized by the American disease know as ‘libertarianism’ or ‘the state as bogeyman’ and went the route of Buchanan and von Hayek in deciding that that power was only evil, twisted and self interested.

Of course it goes without saying here does it not that we are used to seeing this reaction from the U.S. because what it is, is simple?

It’s just a gut reaction on behalf of vested interests who cannot tolerate or share any notion of power or sovereignty even with an elected government.

And how so typically fascist for a vested interest to accuse a countervailing argument of the crime that those vested interests are actually guilty of eh?

I’m very disappointed. It’s as if the cold war never ended.

Congratulations for sticking your neck out.

Nowhere else in the democratic world has such belief in the ‘malevolent state’ as the USA. Despite constant rhetorical reference to the Revolution, I think the ‘freedom’ theme is more to do with the power of rich men (mainly men) to make more profit and gain more power.

With MMT the theory says a govt can fund itself without having to please that class of people-the Bond market. We can remember during the euro crisis every measure occasioned the remark ‘what will the markets think?’

Hence, in my opinion, the hostility towards what for most people would seem to be a better way of running the economy.

Thanks

Of course modern America will be led by its own, modern preoccupations, but the 2020 elelction and Trump problem that we see still playing out, I feel stems from the post-Crash (2007-8) legacy; when middle-rust-belt America suddenly realised Washington had beytrayed the old Main Street, bedrock American dream – for Wall Street: never forgotten, never forgiven. Read Borofsky, ‘Bail-out’ (mortgages, mortgages, mortgages; bailout the Banks, foreclose on Main Street).

But there can be little doubt that the ‘malevolent state’ which the founding fathers had in mind was – Britain. So many of them were running away from the Britain of the seventeenth, eighteenth or nineteenth centuries; or exiled there and driven out by a British state that saw them as inconvenient, outcasts, religiously troublesome or surplus to requirements (exported or exiled as beggars, criminals, Jacobites, rebellious, wrong religion, indentured, land cleared, pirates, or slaves – I am sure I have missed several reasons that made life in Britain unendurable, or forced people out). Even after that, we still cannot make a fist of what is left, without a Brexit or making a mess of immigration or emigration; or the borders inside Briain, or outside. What is the core problem here?

Britain.

Thanks for that very much Richard. As an accountant it is easy to see that MMT as a theory of macroeconomics is tautologically correct when describing the economy we live in (and shows how fundamentally wrong mainstream economics is about everything in its purview – Bernanke, Nordhaus, Mankiw etc being hand in hand with Fox News in spreading disinformation over the last few decades.)

The JG is obviously a policy prescription that may or may not follow from the theory – but it certainly isn’t up to a central committee comprising Mosler and Mitchell plus a few selected quotes of others by them (nor their followers) to decide the definition of MMT. It does seem though that in trying to deal with the coming climate crisis there will be far more many jobs required than people available to do them so the JG proposal is probably not needed anyway.

I haven’t commented here before but have been reading your blog for about 3 years (after reading in Bill Mitchell’s blog some controversy then – I now read your postings daily and his very occasionally). Even as an outsider (Australian) to UK issues there are always very interesting postings here, not only the blog itself but the comments from your regular posters are very much appreciated and food for thought. Even the troll posts are worthwhile as demonstrations of gormlessness by them.

Looking forward to your discussion with Steve Keen very much.

Thanks

Appreciated Geoff

FYI

The Job Guarantee becomes obvious to someone that understands MMT.

MMT points out that the government imposing tax obligations causes ‘unemployment’ ….” and notice that it immediately after saying that specifies what is meant by unemployment. And that this definition of ‘unemployment’ may differ slightly from what you are instinctively thinking it is.

Step 1 – On day 1 the government imposes tax obligations payable only in its currency and explains the consequences of failing to pay. This immediately creates unemployment as MMT defines it.

Notice how on day 1 there is no currency available to pay the tax and everyone is in jeopardy of facing the consequences of not paying. Everyone is therefore immediately, as a result of Step 1, either unemployed or preferring the specified consequences.

Step 2 – The government can then hire employees and purchase what it needs to be a government and in the direction of performing its goals. Why? Because unemployed people are willing to acquire the currency they will need to pay taxes.

Step 3 – The government collects those taxes, because otherwise, it cannot repeat the process. If there are no taxes, no one cares about acquiring the currency. Collecting taxes is required to make the taxes real and therefore to drive people to use the currency.

It then follows that

IF there are still unemployed people after the government has made all the intended purchases, a benevolent government would implement a Job Guarantee program so that the remaining people can acquire the currency they need to avoid legal jeopardy. A cruel government would only impose the consequences and risk revolt.

We do not have the Job Guarantee program, therefore we do not have the benevolent option implemented leaving us with the other.

You prove the need for the JG by arguing tax comes before spend

And you assume that there was a moment when what you sy happemed

Neither is true

That is not a proof of anything

The fact that spend cones first is critical

The creation myth is unnecessary

Apart from that there is nothing wrong in basing an economic policy on false claims and flawed logic?

That is a very interesting and useful piece. Aside from the rights and wrongs of the arguments outlined, can I just say that I would much rather be taught by you, Richard, than Mosler who can’t be bothered to explain why he believes what he does. Your explanation of the mechanism of MMT is very clear and coherent. This is why academic differences need to be debated openly and respectfully so that an improved theory (or at least an improved understanding) emerges. It is not about taking up a position and defending it to the bitter end – that is merely vanity, which the ‘founders’ of MMT seem to be seduced by.

Please continue to agitate for clearer arguments.

I will

And thanks

It’s an interesting disection of MMT theory and what it diffetent interpretations there are.

Does MMT take in to account a refusual to accept the currency outside of their control with another anpther party i.e. a resource or asset that can not be bought with it’s currency?

Does MMT assume that not offering or selling to other parties or countries assets or resources they have in supply in either their own or other currencies or swapping like for like in a barter type exchange?

I mean this in terms of how to count adequetely in terms of value? Does MMT count Value correctly?

I admit I do not follow either of your questions

As to value – MMT is a theory of value crteated from exchange and taxation

This is so important! I’m always grateful that you and Steve Keen (and a few others) bring up the role of private banks – I’ve never been able to ‘buy’ the official MMT line. From your blog: ‘As such tax is not only payable using the money created by the US government; it can also be paid using dollars created by the US commercial banking system, which dollars are indistinguishable in use from those created by the US government.’. Thanks Richard-really appreciate your posts/this blog! Also Dr Dirk Ehnts is doing some really interesting work on/with MMT!

Thanks

@ M McAuley,

“US taxpayers can make settlement of their tax liabilities using either US government created dollars or US bank created dollars, the two being inseparable in use.”

This would perhaps be correct if the word ‘seemingly’ was inserted before ‘inseparable’. We tend to just think of a dollar as a dollar. Most of the time that’s fine because the financial system is relatively stable. Those who held Silicon Valley Dollars recently might well have had cause to appreciate there is a real difference. They’d rather have a had a pile of crisp banknotes of central bank issue.

Any bank can create an IOU denominated in dollars. Most of them are cancelled by contra in the clearing system at the end of the working day. Any imbalance can be requested to be made good by payments from the bank’s reserve account at the central bank. The government is a major player in any economy and so has its own bank which can also issue IOUs and we call base money but is really the top of the pyramid in money terms.

So when we pay our taxes we notice that the dollar amount (or £ amount in the UK) has fallen in our bank accounts. The bank has cancelled the IOUs it has given to us and will transfer them to government. These must also be cancelled by contra. Effectively the private bank is making a payment to government from its reserve account at the central bank to settle the tax bill.

I really think that, as I have already suggested in a blog post, you should not choose selectively from double entry Neil.

As I have already shown, the existence of central bank reserve account deposit balances by commercial banks is not a pore-requisite of their being used to pay tax: the commercial banks could arrange the payment and move into a liability position with the central bank.

In that case the money they create is used o pay them and they use an IOU, not government-created money, to pay the Treasury.

You should also be open about the fact that of course most commercial bank money is not cleared at the end of each day: significant balances remain in the economy.

And the claim in your last sentence may not be true. Base money created by the government to pay tax need not be used, albeit it usually will be.

Sorry, but I think double entry proves you wrong.

I am surprised with the lack of traction on twitter?

Any interest from

any journalists or news services?

The MMT crowd seem to have decided to steer clear of it – at last as yet

I suppose it will take a while for the MMT to digest the arguments and to formulate a response. It would be disappointing if there isn’t one!

I hope this has been sent to journalists and news services? Any hope of it being covered?

I have not sent it

I do not think it would get any coverage

Thanks so much for this Richard. I am a long-time reader of your blog but rarely comment. I found this incredibly useful. I tried to engage with Bill Mitchell’s and perhaps Warren Mosler’s output a few years ago but found it hard to follow and obscure. I put it down to my lack of understanding on MMT but maybe it was just unclear and contradictory!

It’s so important for the public to engage with the reality of MMT, but so hard to talk to people about these matters. I’ve tried it, and maybe it’s my delivery but I get accused of lecturing (not a good approach with family and friends). And it certainly doesn’t help if the proponents of MMT aren’t 100% clear about what they are saying. Your language is direct and open, in contrast to others.

I’ve been trying to get to grips with the way the monetary system really works since the financial crisis of 2008/9, when QE was put into operation. I worked on the Financial Times at the time, and I don’t think there was a clear understanding of what QE is or does among the journalists there (including me).

I first understood that banks create money when they make loans when I attended a talk by a founder of Positive Money at the Occupy camp at St Paul’s in 2011. I tried that idea out on my colleagues and got little help. Martin Wolf has embraced it but you will still see stories in the paper claiming banks lend out depositors’ money, which is really shocking.

There was a real omerta on the subject, even after the 2014 BoE confession, or maybe confirmation. That openness didn’t last of course. And it’s even harder to talk about MMT. People find it so hard to understand something that is really quite simple (I know the actual workings of it all are a bit more complex but the ideas are pretty simple, as you’ve explained).

So thanks again for helping my understanding, of MMT and much more. You probably won’t hear from me again for a while, but I’ll be hovering in the background.

Pauline

Thanks for your comment

And a lot of people hover here, and that’s fine be me

Richard

QE – Quantitative Easing – The Central Bank exchanges its bank reserve form of government currency with the retail banking system to acquire the government bonds denominated in the same unit of account.

So QE is essentially an asset swap, financial instrument for financial instrument of equal value. So this is not a significant change in the amount of financial assets in the economy and the banks are not getting rich because of it. If anything the banks are giving up a higher interest earning financial asset for a lower interest earning financial asset that pays whatever the interest rate of bank reserves may be.

The expectation of those implementing QE is that banks will then increase their lending. But this is a mistaken idea because:

1) Banks do not lend reserves to the public, instead their lending takes the form of more bank credit creation. The bank credit is a promise to pay bank reserves on demand, which they could already do before QE. Nothing about QE increased their ability to lend and the banks already had the ability to acquire bank reserves from other banks if they ran out, or worst case could borrow from the central bank.

2) QE actually added difficulties to bank lending because of Basil 3 rules. Any bank increasing the amount of bank credit (bank deposits) on its books changes ratios that are required by Basil 3 to stay in certain ranges. So in order to allow the banks to lend, the central bank had to offer an option to correct these ratios using operations in the repo-market. If the central banks did not do this, the banks would become unable to increase lending because of QE.

Have you read what I have written about QE since 2010?

Hi Richard,

I’ve read and listened to a lot of output by both Warren Mosler and Bill Mitchell. I don’t recognise their thinking in what you have interpreted here. There seems to be a problem of false assumptions or jumping to conclusions. I’ll try to get the time to argue a few of the glaring examples (with media to back it up) over the next few days. (Unless someone else beats me to it).

I used their words.

Just address what they’ve said, I suggest

I find it hard to see how the can be interpreted another way, but I look forward to a credible counter argument

Richard,

There is a lot I could comment on here but let’s just focus on the tax issue. There is no contradiction between the statement “the first order purpose of tax liabilities is to create unemployment in terms of the state’s currency” and “spending precedes taxation”. Mosler is saying the tax *liability* precedes spending, whereas settlement of taxes can logically only occur after spending. This is a core MMT proposition (maybe THE core MMT proposition) and is a documented historical phenomenon (see: US colonial currencies, or this paper by Forstater on colonial currencies in Africa: https://modernmoneynetwork.org/sites/default/files/biblio/RiPE%20Forstater.pdf). The purpose of the tax liability is to create seekers of paid work (unemployment) in the state’s currency so that the state can provision itself. The state can use this power to fully employ all idle resources/labor.

Charlie

I have posted a blog in reply to this

Very good read, it mirrors some of my feelings with Moslers cryptic explanations. I have tried to address them with him on Twitter, and just get more cryptic responses.

Keep up the good work you do Richard, its very clear a lot of people appreciate you, as I am one of them.

Thanks Ty

All this work and effort and absolutely no response from the MMT fraternity.. it is so frustrating and disappointing!!

That is an issue for them.

I am trying to make MMT accessible and comprehensible. If they don’t want to do that, so be it.

@Stuart,

They are in Richards Twitter thread, mostly arm chair economists living in their own echo chamber. I lose a little bit of faith in the MMT movement everyday. I might add, I am more of a Wynne Godley stock flow consistent type of guy, that pre-dates Mosler and company. I started following Steve Keen years ago and that’s how I found MMT, at first I thought this a great, a top down stock and flow view of the financial operations between the Tsy, banks, and CB. Over the years I have come to learn there are a lot of cryptic “add-ons”. That I can’t seem to address with anyone from that camp without being attacked, this has now lead me to Richard, and his insights on some aspects of MMT.

Thanks Ty

At its core MMT has obvious appeal

I am highlighting all the problems with the add ons

Some is happening….

@ Richard,

Amazon has quoted you on their “Deficit Myth” page as saying about Stephanie Kelton’s book:

” The Best Book About Rethinking Economics that anyone will find”

No disagreement from me there!

Yet Stephanie herself clearly agrees with Mosler’s line on MMT. As I mentioned yesterday she credits him with the change in her thinking during her time as a PhD student. Presumably we all agree that Stephanie is highly intelligent yet you’re saying she allowed herself to be more than merely influenced by someone who can’t provide an “explanation as to what MMT really is”.

She also has quoted Warren in her book as follows:

“The government doesn’t want dollars,” Mosler explained. “It wants something else.” “What does it want?” I asked. “It wants to provision itself,” he replied. “The tax isn’t there to raise money. It’s there to get people working and producing things for the government.”

This is not to say that there can never be any disagreements between advocates of MMT. However, they really need to be resolved in the right spirit. They should never become personal.

Sire, I endorsed the book

Stephanie says a lot that is really useful

And she was influenced by Mosle

I am not convinced she agrees with all he says now

People move on, you know

And I explain how Mosler’s claim can be justified in my blog post. That does not require the absurd reliance on Forstater’s paper and all the really unacceptable assumptions in it

As for not being personal, See what Steven Hail had to say in defence of me in the original Twitter thread. He was not criticising me (I asked). He was criticising those from the MMT community attacking me.

So please do not make it personal, as you bare wont to do.

“The US economy does not have to sell services or assets to the US government to pay taxes. If they refused to buy those goods and services the government has to sell, as is their collective right within that economy, then the tax liability to the US government would not exist.”

Not true. Tax liabilities exist because the government says they do. Sovereign. They do not arise from the private sector opting to buy something from the government, they mainly arise because the government demands a fraction of the economic activity that occurs within the private sector. And the “services” are “provided” because the government decides to do so. There is no referendum deciding which highway to build or how many soldiers to hire.

This is the last of your comments I will post

First, you do not quote MMT’s argument on tax. I guess you haven’t been following

And second, you ignore democracy. I don’t

You really are a time waster

I struggled to get to terms with the Job Guarantee aspect of MMT when I first came across it. It did seem initially to be rather a waste of human resources. Though I was also aware of Keynes suggestion many years before.

“If the Treasury were to fill old bottles with bank-notes, bury them at suitable depths in disused coal-mines which are then filled up to the surface with town rubbish, and leave it to private enterprise on well-tried principles of laissez-faire to dig the notes up again (the right to do so being obtained, of course, by tendering for leases of the note-bearing territory), there need be no more unemployment and, with the help of repercussions, the real income of the community, and its capital wealth, would probably become a good deal greater than it actually is.”

On reading this post I think Mosler is saying that tax collected in an economy that is not at full employment( a difficult target to measure I know) it is a missed opportunity because that tax could be put to better use employing someone to do something….anything… and also made such workers more employable by the private sector. Personally I’d say investing/employing in green tech would currently serve such a purpose….and surely better than mining bank notes!

If that is what Mosler is saying (and who knows?) then he is still wrong. That is because tax paid does not prevent employment. It creates alternative employment. That employment might be better for society. It might have a higher multiplier effect attached to it. It is most definitely part of national income. The idea that it might simply be a black hole into which money is poured is wrong.

What?

“The idea that it might simply be a black hole into which money is poured is wrong.”

Does a theater have more ability to give out more tickets when it receives the tickets back?

Does an airline have more airline miles when it receives airlines back?

Answer to both is no.

The government receiving back its currency in tax payment does not acquire the currency that it pays out. It pays out currency by increasing the size of numbers of bank accounts and receives currency back by decreasing numbers in bank accounts.

So:

When the economy gives up currency to the government in tax payments, it has less of that currency with which to support employment. So it is necessarily true that paying taxes increases unemployment.

And your assumption is that there is no spend

Now since MMT says tax comes before so end – a fact now established – you are right that tax reduces employment

But since that is not what actually happens and seems actually comes before tax what you say is wrong and tax controls inflation

MMT needs to talk about spend coming before tax and then it makes sense

Re: “‘As such tax is not only payable using the money created by the US government; it can also be paid using dollars created by the US commercial banking system, which dollars are indistinguishable in use from those created by the US government.’”

My understanding is that commercial banks do not actually create dollars but rather “promises to pay dollars”. The banks make entries on their books and if depositors want actual dollars, then the banks will obtain them from the central bank for distribution. I would argue that there is a clear distinction between “dollars” and “promises to pay dollars” which can be seen especially during bank runs when the customers of the banks line up for actual dollars because they do not have trust in the promises.

To argue that tax liabilities can be extinguished with “dollars created by the US commercial banking system” is in my view misleading. Ultimately, the government does not accept “promises to pay dollars” in payment of taxes. In the payment of taxes, the bank acts as the taxpayer’s agent, and must hand over actual government-created dollars (settlement balances) which are then extinguished. I say “ultimately” because there are holding accounts (TT&Ls) but these serve to only delay the process.

Treasury tax and loan accounts (TT&Ls)

“TT&Ls are accounts of the Treasury at private banks. These accounts were first set up in 1917 to receive proceeds of Liberty bond offerings, and in 1948 they also began to receive tax collections. The Treasury does not spend out of these accounts. When it needs to spend, the Treasury transfers funds from its TT&Ls to its general account at Federal Reserve. The Treasury general account (TGA) is the main part of L2 and transfers of funds from the TT&Ls into the TGA drain reserves (L2 goes up, L1 goes down) (U.S. Senate 1952, 1958; U.S. Treasury 1955). TT&Ls were created explicitly for the purpose of smoothing the impact of Treasury fiscal operations on reserves (part 3). For example, when the Treasury receives tax payments, it does not immediately transfer funds into its TGA, but keeps them in its TT&Ls. This helps the Federal Reserve tremendously in estimating the reserve-supply conditions in the federal funds market, and thus to know how many OMOs are needed on a daily basis (Bell 2000; MacLaury 1977; Meulendyke 1998; U.S. Treasury 1955). ”

A Primer on the Operational Realities of the Monetary System

Scott T. Fullwiler

Wartburg College; Bard College – The Levy Economics Institute

“the very act of paying taxes (when the taxpayer’s bank settles with the Treasury) or purchasing a Treasury security is also the “destruction” of reserve balances, while (6) the act of government spending is the creation of reserve balances.”

I fully understand the operation of central bank reserve accounts and have written about and explained all that on this blog well before now. I think you may need to read that material.

Where you go wrong is on this:

That is wrong. Banks create dollars. They just do not create base currency.

But, let’s also be clear that there is no base currency in circulation in the economy, excepting the tiny part of the money supply made up of notes and coin. Base money does not kve beyond the central bank reserve accounts. It cannot.

So in that case tax can only be paid in commercial bank-created dollars. Period. End of. Full stop. There is no other way that it can be paid. Base currency is not available to pay it because you and I do not have it: we have commercial bank-created money.

Commercial banks settle tax back with the Treasury in base money. That is true. But they do not actually need base money o do so. They could overdraw their central bank reserve account and the system would still work.

If someone asks me how a radio works, I can certainly tell them that one turns an knob and music comes out. While my explanation is not inaccurate, it does not inform about the vital innard workings of a radio that enables it to receive information via radio waves.

Similarly one can argue that taxes are paid by using commercial bank deposits, but that glosses over the essential information relating to how taxes are paid beneath the surface transaction. MMT analysis posits that ultimately taxes are paid with settlement balances that are then extinguished.

I do not find persuasive the argument that settlement balances aren’t even needed because a commercial bank can operate with an overdraft . My understanding, and please correct me if I am wrong, is that the commercial bank will have to rectify it’s overdraft by obtaining settlement balances and transferring them to the central bank. So the MMT thesis is not disproved, the ultimate transaction is merely moved one further step down the line.

Your efforts to make MMT concepts more widely understood among the public is appreciated.

Thanks

You are the guy to explore that possibility! And – You are the guy who could make MMT go viral with a few such tweaks!

Keep up the great work!

There will be more this week

Superb response to a superb post by Larry, whose encyclopedic knowledge I envy!

Your response is supported by several central banks which have recently published papers on CBDCs. For instance in the following Fed Paper there are two direct quotes.

“Cash is currently the only central bank money that is available to the general public, and it remains an important and popular means of payment.”and

“Federal Reserve notes (i.e., physical currency) are the only type of central bank money available to the general public.”

https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/money-and-payments-20220120.pdf

Correct

Electronic base money is not available to the public

Richard why can’t settlement balances be used at the banks? My inexpert impression is that settlement balances are just CBDCs without the privilege of being used by the banking system. They, like private bank digital currency, can be exchanged for currency. Logically shouldn’t settlement balances be useable by the public. It is just a legal permission thing?

Thanks

Have you read up what I say on the blog and glossary about central bank reserve accounts, how they are created and what they do?

I can’t repeat it all.

In essence, they are not CBDCs and are not meant to be.

I couldn’t find something in the glossary, but I read the following posts on reserve accounts, interests on them and CBDCs which explained your perspective and illustrate your expertise.

For the first two articles I would suggest if CBDC’s existed on the wholesale level, much of the complexity of the system could be simplified. Most people with a bit of background understand that if the banks sell bonds to insurance companies and pension funds, their balance sheet shrinks. Such people and apparently the National Institute for Economic and Social Research (NIESR) are baffled by the dynamics you explained for reserve accounts. But if the CBDCs were used, when the central bank bought the banks bonds, the banks balance sheets would shrink. … And there would be no reserves to pay interest on.

https://www.taxresearch.org.uk/Blog/2022/06/17/how-are-the-central-bank-reserve-accounts-created/

https://www.taxresearch.org.uk/Blog/2022/11/21/why-the-niesr-is-wrong-on-interest-payments-on-central-bank-reserve-accounts/

https://www.taxresearch.org.uk/Blog/2023/02/07/the-uk-does-not-need-a-digital-currency-the-vanity-of-central-bankers-does/

https://www.taxresearch.org.uk/Blog/2023/02/08/what-is-the-bank-of-england-for-if-its-plans-for-a-digital-currency-are-so-incoherent/

I think this is an issue to explore

I’m afraid my mind started to turn towards angels and the heads of pins. These are part explanations, though I find Richard’s a lot better than Warren’s.

When I was a working scientist, if looking for a promising research project, I always thought contradictions were a good place to start. So that I find arguments between factions disappointing. The important message is that there may be something interesting hiding and that is what we should be looking for.

That is what me explanation paper was all about and why it came first