A new article on Bank Underground, which publishes staff papers written by personnel working at the Bank of England, is interesting. Written by Galina Potjagailo, Boromeus Wanengkirtyo and Jenny Lam, it focuses on the underlying causes of inflation. Its opening premise is this:

The recent rise in UK inflation was initially fuelled by two large external shocks: supply bottlenecks along global value chains due to the Covid-19 (Covid) pandemic (for instance, with microchips and used cars) and soaring energy and food prices related to Russia's invasion of Ukraine.

Having then noted that the prices in question are set externally to the U.K. the authors suggest:

However, broader domestic price increases via ‘second-round effects' can follow because energy prices affect the costs of many other goods and services through their role as indispensable input in production and transport.

So far, so good, and I agree. The second claim can't be disputed in some cases, although its significance can be.

What they do next is interesting. What they argue is that there are four causes of inflation right now:

- The Ukraine war

- Covid reopening (which they assume is now taken over by a war effect, but may be continuing)

- Idiosyncratic inflation e.g. that in second-hand car prices because of shortages of chips to make new cars

- Remaining inflation (underlying inflation, or UIM as they call it). This can include secondary effects from the above.

The split makes some sense, although it is unsophisticated on secondary impacts without cause being established.

Their first iteration of this is as follows:

As they note:

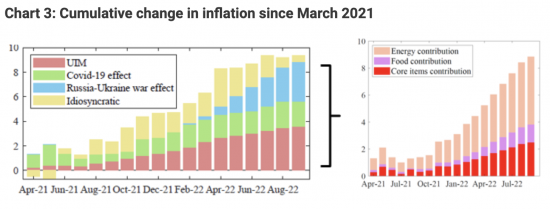

In September, the historic underlying inflation measure (red bars) has reached 5.8%, the highest level observed over the sample period, having increased by 3.6 percentage points in cumulated terms since early 2021.

They add:

It is ... comparable to the Federal Reserve's estimates of US underlying inflation (6.0% for September).

But they do not then accept this as the final answer on underlying inflation. As they note:

The bulk of the increase in underlying inflation is due to broad-based energy price increases, suggesting that energy prices have increasingly comoved with other prices. Chart 3 decomposes the cumulated increase in UIM, the Covid and Russia-Ukraine war effects since March 2021 (overall 8.8 percentage points). Almost two thirds of this increase came from broad-based increases in energy items' prices (5 percentage points), and a much smaller contribution of 1.3 percentage points came from broad-based increases in food prices.

They argue:

These broad-based increases in energy and food items contributed not only to the more erratic Covid and Russia-Ukraine war effects, but also to the UIM. The effects on underlying inflation should, in principle, decay once the external shocks behind energy and food price spikes subside.

They are quite clear that they expect this to happen:

The effects of these components should fade out relatively quickly as the two shocks subside – we therefore view them as another type of erratic component rather than as part of underlying inflation.

In other words, they are quite sure that as the first part of Chart 3 shows, core inflation is at present under 4%, and as the second part shows, once the impact of conflict (in particular) is limited in the calculation of inflation (which it will be by mid-2023, because by then inflation calculation will compare post-Putin war prices with post-Putin war prices) then inflation might be under 3%.

The authors then reveal their Bank of England colours, saying:

However, the fact that these items have moved jointly with many other UK price items indicates that the external shocks might begin to propagate to domestic price pressures.

I suggest 'might' is doing a lot of heavy lifting in that sentence. It should actually say 'should', because people will need to recover their purchasing power. But the reality is that the inflationary impact of this is going to deliver inflation only a little over the 2% arbitrary target set for it.

The authors conclude:

Our finding of a rise in underlying inflation among core items suggests that the inflation in the UK is partially driven by broad-based increases in prices that are typically rather stable. Over the past, shifts in this component have been quite persistent, so it could plausibly remain elevated. The precise link between the breadth of price increases and inflation persistence in a high inflation environment remains an open question relevant for central banks.

My suggestion is that the data strongly implies three other things.

First, inflation will decline significantly next year. There is no reason to increase interest rates to make that happen: it will anyway.

Second, Bank of England monetary policy is fundamentally flawed as a result: this analysis shows that.

Third, the right question to ask now is whether a 2% inflation target is reasonable for the next two or three years as spending power is restored. Wouldn't a year at 4% and two more at 3% make sense in that case? And then decide if 2% might ever make sense again, I suggest. Underlying economic factors might suggest it does not. But right now, using this logic, inflation is essentially under control and policy should focus on restoring monetary purchasing power in the economy - which is all down to fiscal policy. In that case, the Bank of England should be doing precisely nothing at this moment.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

Both the Fed and the BofE are aiming to get unemployment above its natural rate as a mechanism to curb wage inflation as if wage inflation grips then it inflation is embedded. That policy is deliberate and known by anyone who follows economic policy.

This is an interesting paper.

First, it shows that within the BoE there is a variety of thinking. It has always been my experience that the BoE and (to a lesser extent) HMT DO have imaginative thinkers – I suspect that most staff will embrace at least a minimalist version of MMT. The problem is that higher up things get political and politicians lack courage/imagination/intelligence (or have ulterior motives) to state the truth and base policy around it. So at the top of these institutions we get people like Bailey.

Second, I think they are right about UIM not being particularly elevated… but also right about “might” in terms of risks to the upside of UIM. (1) We must accept that China is no longer an exporter of disinflation (and there is no potential replacement at their scale). (2) Brexit has damaged our trade position that is (and will keep) depressing GBP which means risks of imported inflation (3) Lack of investment suggests that productivity gains will be limited . Against that we must put the perilous position of households who (as Amazon has indicated) will cut purchases.

Gilt yields (10 year maturity) have fallen about 1% since the mini-budget to 3.75%. So, the market realises what is going on. Given the rhetoric from BoE, it would be tough to go with “no change” in rates. Perhaps the best we can hope for is a 25bp rise with an explanation of why.

If we were to settle with Base rates at 2.5% and 10 year gilts at 3.25 – 3.75% I would consider it a decent result… but don’t hold your breath.

The problem is a lack of honesty from politicians.

First, the cost of imported energy and food means that we will all have less for other things.

Second, we ALL (yes, most Tory voters, too) recognise that we need more defence, better health and education (and more). And if that is what we want more of, we must have less of other stuff…. and this has yet to be stated by politicians.

Third, the things we all want more of are currently delivered by the State. So the choice is either higher spending by government (however that is financed) or forcing people into private provision. (Appeals to “greater efficiency” are nonsense).

So, while many bemoan the fact that Labour and Conservative are two shades of the same colour I don’t think that is true. Tories want private provision as it is (a) a profit opportunity for their mates and (b) delivers more efficient results – despite all evidence to the contrary. Labour want State delivery because it is best and fairest for most citizens.

When the chips are down (as they now are) we see Tory cuts. I would like to think that once in power Labour would do “whatever it takes” to keep public services running… (higher taxes, borrowing and money creation in some proportion or other).

I agree with quite a lot of this

But I fear your rose tinted specs about Labour

You may be right about Labour but we have to hope….. and keep lobbying!

Indeed

Nearer blacked out lenses. Labour speaks vagueness very firmly.

But Clive Parry, a) why “we must have less of other stuff” when the government can fund whatever is necessary assuming the physical resources are available? and b) I don’t see many Labour policies on re-nationalisation.

It has nothing to do with funding or money. We only have so many people and resources. If we want more doctors, nurses, carers, teachers, soldiers we must have fewer chefs, poets, builders etc.. It is essential that we see the economy in terms of resources rather than money.

With regards to nationalisation I do think Labour should be bolder… although my preferred route in most areas is to regulate ever more tightly until the current incumbents “hand over the keys” – it does away with arguments about compensation. And, if the private providers can meet ever tighter regulation (on price and quality) then I am happy to not nationalise.

Totally agree with both ideas

“We only have so many people and resources.”

We have a crisis surfeit of labour shortages; and typically that often means a compounding crisis shortage of labour resources with the skills that are in short supply. Shortages that are not easily addressed, beyond just robbing Peter to pay Paul.

That brings us back to Brexit. Oops, In a paraphrase of Fawlty Towers, don’t mention ….

Conservatives, Labour and Lib Dems are all much more ‘the same’ than people believe, or want to believe; distinguishable political rhetoric is easy, but more often than not it just delivers more rhetoricians looking for an easy way out of difficult choices. They are too afraid of the electorate to tell them what a catastrophe they voted for; and will pay for dearly in the years to come.

Clive Parry

Please could you give some evidence (any evidence) that “Labour want State delivery because it is best and fairest for most citizens.”

I have been looking for evidence of this for a very long time, but I can’t find it.

“Labour wants State delivery” is, I think, self evident…. so I presume you are challenging “best and fairest”.

Have you tried catching a train in Germany, Switzerland, France, Japan? All, I think, better than the UK.

In any case, in the important areas I mentioned I think the “burden of proof” lies with the other way round. Private providers will have a higher cost of capital and dividends to pay… leaving fewer resources applied to actually delivering the service. What makes you think that they can do better?

Good paper, good comment.

“….politicians lack courage/imagination/intelligence (or have ulterior motives) to state the truth and base policy around it.”

The truth is neatly encapsulated in your reference to China (we can do nothing about that), and to Brexit: and we can do something about that; but we eill not do so, because politicians (of the three Unionist parties), will not address the issue, or even allow it the ‘oxygen of publicity’.

The frailty of politicians is one thing, but on Brexit they are scared witless of the electorate, run away from the problem, and will not even discuss the matter. Nobody will even debate rejoining the Customs Union or Single Market. The whole issue is now literally a taboo subject in the British political mainstream. We have airbrushed Britain out of the real world, to inhabit an illusion fantasised by Boris Johnson and Dominic Cummings; remember them? Here is a clue – they were big once.

In Scotland we look on in utter disbelief. They want us to stay in the Union – for this?

@Clive Parry

No, I do think that ‘Labour wants state delivery’ should be self evident, but the evidence points the other way. Starmer has categorically denied intention to nationalise the energy companies as recently as August this year, On rail there is evidence that he is in favour and against nationalisation.

If like me, you believe that interest rate rises are actually meant to help inflation benefit rentiers by upping rates, then there is no way in hell that the Bank of England will be paying any heed to this paper.

The 2% target is ‘project fear’ isn’t it and helps to contribute to the argument to retain or increase interest rates. The BoE is there to help the rich maintain the value of their funds – period.

Wouldn’t a year at 4% and two more at 3% make sense in that case?

Those numbers look like arbitrary targets to me.

So is 2%

Made up by the Bank of New Zealand as I recall

No logic to it at all

For those with little knowledge of economics,

1 Why do we need aggregate growth? More SUVs, a greater variety of coffee jar shapes, more climate-damaging flying for pleasure, private education, dentistry and health care (by people trained at the state’s expense) …

2 John Major said, ‘I hate inflation’. Why should ordinary folk like it? … at 1% or 2% or any other %?

Chapter and verse on the New Zealand origin here

https://archive.ph/nChld

Thanks Peter

Quick question that I am struggling to understand. Totally agree with your analysis but wonder what the affect will be of current inflation rate pay rises. Will these not filter in and start to drive inflation upwards again? Help me understand how this is worked through the system. Thanks

If there is less than full employment (and there is) and overall wage rises lag prices there can’t be an inflationary effect for that reason because there is only a correction to restore earning power in that case

But if current price levels are the result of increased costs, adding increased wages must, surely, result in a further price rise. Or, perhaps, a reduction in dividends paid to shareholders. Or a reduction in board room salaries.

Don’t get me wrong, I think there is a vital need for wages to be at proper levels to allow people to live without the government having to subsidise their employers and shareholders by paying in work benefits. But I think it needs a very large refix to achieve that. As Richard has been arguing for some time.

Current price rises come from increased profits

but we need overall deflation to get prices back to where they were 12-24 months ago when prices and the general cost of living were stable. Any further price rises from here is a disaster. So even we really fo t want any inflation from here we want and need price falls.

There is no problem if wages rise

“There is no problem if wages rise”

What if you are retired and have no ability to earn and are living off a pension where inflation is capped and savings where returns are disastrous?

Inflation is awful

Accepted

But not everything can be changed controlled

And I call for pensions to increase by infhation

“If there is less than full employment (and there is)”

This is not true!! …You obviously havn’t had a job for a long long time. I have been running my own company for 25years and it has never been harder to recruit skilled labour. Part of the problem I think is now more than half of 18yr olds going to university where many are sub standard establishments teaching pointless humanities courses with no vocational worth.

You mean they have rumbled you are offering shit work on shit wages? Easy to solve that one

“You mean they have rumbled you are offering shit work on shit wages? Easy to solve that one”

so you know many experienced roofers do you? If you do send them my way. We pay daily rates of £230, or maybe that is too shit to bother getting out of bed??

Did you vote for Brexit?

“Did you vote for Brexit?”

No I didn’t but we are where we are..and in the UK we have near full employment in the building, engineering and manufacturing industry..that I absolute guarantee so what you say is wrong. If I have too pay higher wages to attract staff from other companies then my prices will go up..that is inflation

And since wages are dragging way behind price rises generally that is not true

There are a few comments about labour problems and lack of people to fill vacancies.

Looking at the labour problem from my own (former) profession POV. Something like 20-30% of the entire UK airline pilot workforce lost their jobs when Covid struck. Thanks to Brexit they also lost the right to work in the EU and because of the totally dumb ideologically driven decision to leave EASA, and the lopsided Aviation TCA deal, they also lost their EU licence and now can only work on UK registered aircraft. (Most Ryanair aircraft based in the UK are EU registered).

Despite the 6 years of rhetoric about ending freedom of movement, and the UK Government’s stubbornness about restricting immigration for the so called “Unskilled Workers” that we so desperately need, freedom of movement is very much alive and well at the “Skilled Worker” level, but in one direction only.

Despite the difficulties UK pilots are having getting back into the workplace (fading skills, out of flying currency, etc), Skilled Worker visas are already being issued by the Home Office for overseas pilots to come into the UK. It also seems that the Gov are now intending to make their Skilled Worker route even easier.

In this example, we have plenty highly motivated people with the right skills wanting to get back into work, but the post Brexit system will not let them. I am sure similar problems exists in many other sectors.