Having taken a quiet Friday afternoon I posted this thread to Twitter this morning:

We are continually being told by Tory politicians and the Bank of England that businesses must not give employees pay rises that might match inflation because this would create an inflationary spiral. But what about dividends? Aren't they the real cause of the problem? A thread…

The data I am using in this thread was researched by me with @adamleaver and others at Sheffield University Management School and Queen Mary, London, which is available here. https://productivityinsightsnetwork.co.uk/app/uploads/2021/06/PIN-Report-29-6-21-FINAL.pdf

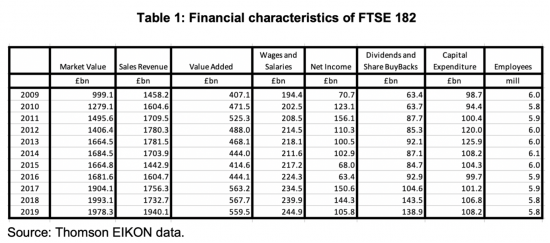

We researched 182 companies that had continuously been in the FTSE 100 from 2009 to 2019 to provide data for the research. Some of these are amongst the biggest companies you've heard of. Others are somewhat smaller. The sample is broadly based.

The findings were pretty staggering. What we were looking at was:

- Profitability

- Rewards paid to shareholders

- Employee costs

- Investment

- Borrowing

- What companies were investing in

What was apparent from the data was how odd it was. If 2009 is ignored as a year of crisis the value of these companies grew by 54% in a decade but sales only grew by 21%, and added value was further behind at 18.6%.

What is also apparent is that whilst employee salaries grew by 21%, profits on average fell but shareholder reward payments like dividends more than doubled with those at the end of the decade 218% above those at the beginning.

Notably, the number of employees in these companies was virtually stagnant over the decade and capital investment went up by only 14%, with some variation on the way, with 2012 and 2013 being the best years by far.

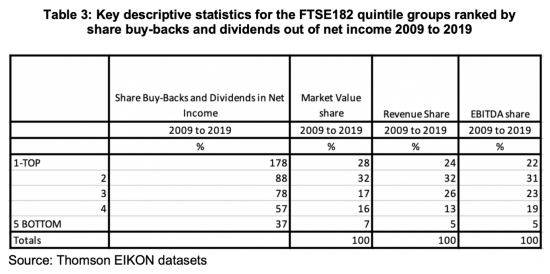

But this is not all that was weird. We then split these companies into five quintiles, which simply means we ranked them into groups of 36 or 37 companies each. We ranked them according to the percentage of their net profits that they paid out to shareholders and got this data:

The top 36 companies paid out 178% of their profits on average. The next 36 or so paid out less: they only rewarded their shareholders with 88% of the profits earned. Together these companies represented 60% of the market value of the companies surveyed and 56% of all sales.

As is apparent from the data, smaller companies paid out less of their earnings to their shareholders. Relatively speaking they were also worth less.

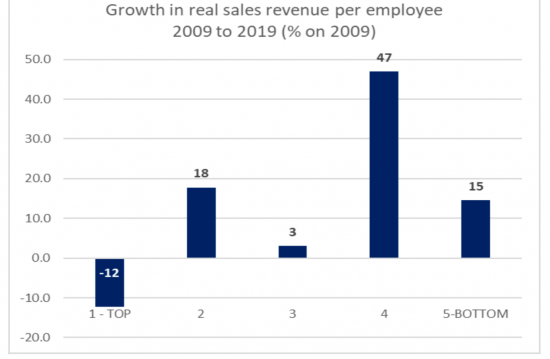

However, looking at the data on how these companies actually behaved suggested that these valuation differences were hard to justify. Take real sales growth, for example where real means that we have eliminated the impact of inflation:

The companies overpaying dividends actually saw their real sales fall. The second group fell well behind the fourth group and hardly bettered the fifth. Value was clearly not related to ability to really grow a company.

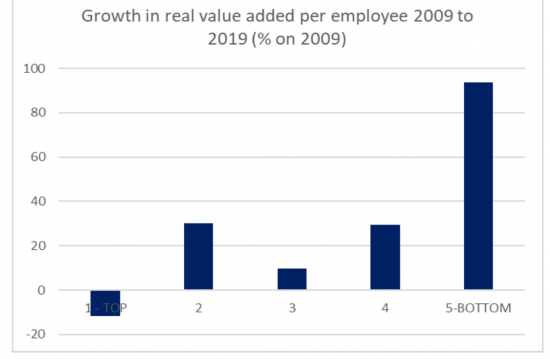

Then we looked at real added value per employee (i.e. again, inflation adjusted). This might be thought of as a measure of just how much of the growth within a company is really generated by its own skills and those of its employees.

Again, the top group did really badly. Their performance actually declined. The companies paying out least by way of dividends out of earnings did best, by a long way.

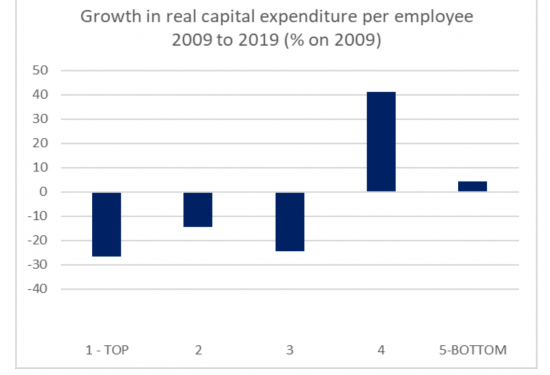

This may not be surprising: we then looked at investment in capital per employee, with the comparison by employee letting us rank the companies consistently whatever their size:

The companies who paid out less by way of dividends invested more in new capital equipment per employee. No wonder their real value added per employee was better.

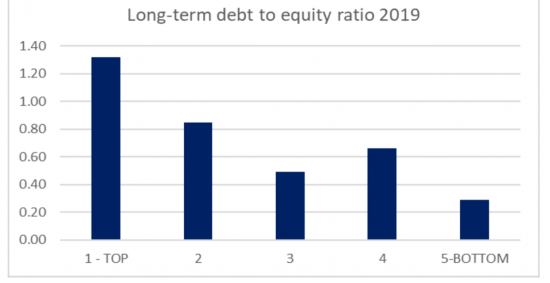

So, then we asked the obvious question, which is how do these companies that pay out more by way of dividends than they earn by way of profit manage it? They do, of course, achieve it by borrowing, much more than average:

The less a company borrows and the more it relies on shareholder funds to support its activities (including profit not paid out by way of dividends) the more resilient it is against financial shocks, because it still has the capacity to borrow when the unforeseen happens.

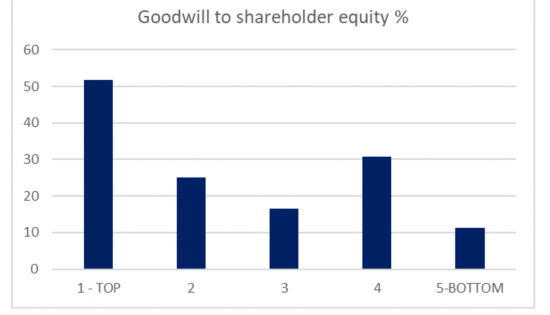

There was another big difference amongst the companies. Those who paid out most by way of dividends had the highest ratio of goodwill to shareholder's funds on their balance sheets:

Goodwill is the amount paid to buy another company over and above the physical equipment bought. Bluntly, it's the price paid to get your hands on the future profit another company might make. The high dividend paying companies are much more willing to do that than the low dividend paying companies.

Maybe this is because they know they lack the ability to grow their own companies that those paying fewer dividends seem to possess.

I do not pretend that this research answers all the questions that could be addressed on this issue. It's also most certainly not investment advice. But it does suggest a number of really important things.

First of all, a majority by value of the FTSE 100 has, over a decade, been paying out almost all, or much more than its profits earned by way of dividends to shareholders, which is staggering.

Second, these companies borrow the money to pay out these dividends. They seek to turn borrowing into excess dividend payments in relation to sums earned to inflate their stock market values, which seems to be working as the companies doing this dominate the FTSE by valuation.

Third, this suggests that these companies are much more interested in financial engineering than they are in actually creating real value within their companies. How they might do this is suggested in a paper I have co-authored here. https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/media/28677/download?attachment

Fourth, as a result these companies under invest, except in buying other companies, in which they might overinvest, creating risk for their shareholders, and employees of course.

Fifth, by looking at those companies that decide not to pay out nearly as much by way of dividend we can see that the behaviour of those companies paying excess dividends is a choice, and not necessity. No law requires them to behave this way, in other words. Their recklessness is chosen.

But, and this is key, the larger companies (by value and sales) who focus on over-paying dividends as if it is their corporate purpose do create real victims in the process. They achieve their result by suppressing wages and real investment, so we have poor pay and productivity.

The companies that overpay dividends also increase their borrowing, putting their shareholders, employees and the economy at large at risk.

And by over-investing in buying other companies rather than in creating real value-added through their own abilities they stress their own balance sheets, and also promote overvaluation of the FTSE as a whole, which is only a short-term gain.

Which brings me to another core issue, which is why do the managements of these companies seek to exploit all those that they engage with, from lenders, to shareholders, to employees, by pursuing these policies? There has to be a reason.

Of course, there is. The management of companies screwing their companies to pay excess dividends do it to inflate the share prices of those companies. And their directors' bonuses are almost always related to increases in that share price. In that case their exploitation pays.

So, when the argument is made by companies (usually the largest ones) that they cannot pay inflation-matching wage rises, what they're actually saying is that they want to continue paying inflation-busting, and very often unearned, dividends instead.

The message is that these companies don't want to pay inflation matching pay rises because they're not interested in employees, the future of their companies, their sales or keeping anyone happy so long as they can by financial engineering keep turning borrowings into profits.

Not every company is guilty of the financial engineering that is going on. The Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales is guilty of enabling it by the guidance it issues on how dividends can be paid, which lets this abuse happen. And corporate greed is guilty of exploiting that advice.

But the truth is that if the largest companies acted responsibly and stopped driving up dividends by making payments they cannot justify they could make the wage payments the UK economy needs them to deliver now to prevent many of their employees falling into poverty.

If business acted responsibly in this way it would also set the tone for all wage settlements. That it is not doing so is by choice. And that choice must be challenged. Even shareholders are at risk from what is happening. This behaviour must end, and now is the time to stop it.

Simple changes to the law could prevent this: Adam Leaver and I have presented those rules to relevant government departments during discussions on audit reform but big business has lobbied hard to keep this situation, and has won it seems.

As a result the likelihood that shareholder rewards will continue to outstrip pay, whilst fuelling inflation and imposing hardship is likely, and all to feed the greed of managers who seem to get to the top of a company and see their once-in-a-lifetime chance to get rich quick.

Finally, my thanks to co-authors Adam Leaver, Colin Haslam and Nick Tsitsianis and Sheffield University Management School for enabling this work to happen. The opinions here are all my own though.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

why else would shareholders put up all the capital unless they make a healthy return? if that return is in the form of dividends then so be it..

the alternative is Marxism

So those directors not paying excessive profits but who are creating strong companies are Marxists?

I suspect they would not agree

Sorry, Stephen, but I read your last sentence with puzzlement.

First, could you particularise what would constitute THE alternative, or even AN alternative to your main thesis?

Could you then explain how, i.e., in what ways, that would be Marxist?

A company can only lawfully pay dividends to shareholders out of distributable profits – that is, accumulated realised profits less accumulated realised losses.

Directors are personally liable to repay unlawful dividends so they will not be doing that.

So how are these top quintile companies turning borrowings into returns to shareholders, without generating the supporting profits? How can 36 companies distribute 178% of profits over the course of a decade?

Please read the paper I linked explaining this

In summary, they pay out of parent company profits, not group profits

Right, but the parent company still needs to have sufficient distributable profits.

Page 16 of the report – which I’ve now had a chance to skim – suggests two mechanisms by which the single company accounts of the parent company might show distributable profits in excess of the group’s net profits.

The first involves reclassifying non-distributable reserves (merger reserve, share premium, revaluation reserve etc.) as distributable.

That is essentially a reduction of capital, which for a PLC will involve a court process. (Private companies can use a directors solvency statement to achieve a similar result, but here is an example of a situation where that went wrong and the directors were found to be personally liable – https://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Ch/2018/600.html )

The second is receiving distributions from profitable subsidiaries, but where there are losses in other subsidiaries.

That is certainly possible, but presumably on the basis that any loss-making subsidiaries are not yet insolvent and no impairments need to be recognised. (And Queens Moat Houses illustrates a situation in which that goes wrong, and again the directors were personally liable – https://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWCA/Civ/2001/712.html )

It might be instructive to consider some specific examples to see if we think these companies or groups are cooking their books. And to see if it is just a handful of outliers, or they are all at it,

Look at major pharmaceutical companies for the disparities on display

But they are so commonplace this is routine

You are also ignoring that this can routinely arranged beyond the reach of UK company law

And look at Carillion for auditors’ attitudes to impairment

Bless you Richard Murphy – I would love to know what the definition of ‘quiet’ is in your household!!

The travails of a well know cinema complex are now hitting the headlines. More of the same perhaps?

One of the things I learnt studying manufacturing firms during my MBA was that even those with stellar reputations like Toyota was that they too had financial trading arms.

Quiet is less stress and only dual tasking

That is absolutely fascinating data, but makes me even more pessimistic about the UK economy.

One question that it elicited in my mind: would it be better to base corporation tax on distributed profit rather than trading profit?

We used to have a withholding tax on distributions that then cancelled CT if appropriate.

I think we need that again

The return of ACT? And a tax credit for shareholders?

Why not?

It worked

What you are describing sounds less sustainable than a house of cards.

Am I right in thinking that limited liability means that when an enterprise collapses the directors can simply walk away from the mess with their winnings intact ?

Usually, yes

Very, very likely in most cases

Great to see one’s suspicions justified in gory evidenced detail! And surely deserving of an outing in the mainstream media.

As someone with a penchant for looking at company accounts, I am often bemused by the linkages between various related entities such as groups and parents – terms that you mentioned in a reply here, and in the linked paper.

Does a group always have a parent? Is there a legal definition of those terms and the rules that apply to how they are used? More usefully (to me at least), it would be really helpful if you could provide, or point me to, an explanation of the terms.

Many of the companies I’ve had occasion to look up at Companies House have had explicit offshore connections, and that often seemed to mean that there are multiple apparently connected entities. In such cases, do the same rules apply?

I think Marx would agree that an employer has to pay a living wage for the continued reproduction of labour in the long term. By not doing this, the capitalists are sowing the seeds of their own destruction as from a marxist perspective labour input is the measure of wealth in a company. A poorly paid labour force is less productive and an overworked labour force the same.

You are not alone.

Takis Varoufakis said on a Youtube interview that when he was young, he and other radicals thought they might destroy capitalism. They never thought that Capitalism would destroy itself but it seems to be on that road.

Agreed

[…] By Richard Murphy, a chartered accountant and a political economist. He has been described by the Guardian newspaper as an “anti-poverty campaigner and tax expert”. He is Professor of Practice in International Political Economy at City University, London and Director of Tax Research UK. He is a non-executive director of Cambridge Econometrics. He is a member of the Progressive Economy Forum. Originally published at Tax Research UK […]

An important thread, and very interesting to me as an investor using dividends as a source of income. I have avoided a lot of disasters by looking beyond dividends to other measures (earnings, free cash flow, debt etc.). However, I have got caught out by sale and leaseback (Debenhams, taken private, assets sold off and the proceedings pocketed. Assets then leased back. Company re-floated, apparently profitable but in reality on a knife edge.) I think of stores that don’t own their stores, airlines that don’t own their aircraft etc. Can you, with your auditor’s eye , identify companies where debt has been concealed as future obligations?

Interesting that Morrisons, unusual among supermarkets in owning its assets, was recently taken private.

I can….but am unwilling to do so

And while this is going on, Liz Truss plans to give these very people who are stoking inflation tax cuts. Does she actually believe this will help tackle inflation? The mind boggles!

Any idea how many staff have lost jobs due to outsourcing or off shoring or any other term for getting cheap labour abroad?

None at all

Sorry

Great thread, Richard.

It will be interesting to see how raising interest rates begin to clobber these companies accounts… can we expect a flood of bankruptcies?

Amongst the indebted ones that is clearly possible, and even the aim of the Bank of England

Having just read this post I saw this in the Guardian about the pay dispute at Felixstowe Docks….a perfect illustration if I’ve understood correctly:

Unite general secretary Sharon Graham said: “Felixstowe docks is enormously profitable. The latest figures show that in 2020 it made 61 million in profits.

“Its parent company, CK Hutchison Holding Ltd, is so wealthy that, in the same year, it handed out 99 million to its shareholders.

Felixstowe, Suffolk, is Britain’s biggest container port and the strike will affect the UK’s supply chains.

Eight-day strike by Felixstowe dockers expected to disrupt UK supply chain

Read more

“So they can give Felixstowe workers a decent pay raise. It’s clear both companies have prioritised delivering multimillion-pound profits and dividends rather than paying their workers a decent wage.”

Fascinating thread, exposes what I have long suspected about the use of purely financial measures to boost market values and hence bonuses. These were FTSE companies but did your research take into account the largely international reach of many of them and adjust to show purely UK activities? Or are we seeing a worldwide problem as reflected in companies listing in London?

No, that would be exceptionally difficult if not impossible to do given how poor that data in accounts is

Thanks Richard. I feared that might be the case. Still massively useful though.

To anne smt

Some years ago my brother had a precision manufacturing business make parts for

a major weighing company which was by far the biggest customer. Out of the blue the weighing company transferred the orders to china. Brother’s closed six months later as a direct result

I guess you have Cherry-picked the starting year as 2009 for good reason!

I did the ratios from 2010

You didn’t even read it

Be interesting to compare against USA. Also would like to see it against a country with strong unionisation. There is also the wonderful world of the private equity industry and I doubt it is much different.

Excellent article Richard.

As I was reading I sensed a parallel with the Banking groups which led to the credit crunch. Am I interpreting this information correctly?

To a air extent, yes

Are we heading for a big crash then?

Has the greed economy siphoned off so much value from the larger economy that its hollowed out?

I wish that people in their millions could “Rise like lions after slumber” and see through all the bollocks that the Tories spout – the latest being that instead of making a big stew to last the week poor people are frittering away their money on takeaways.

To your first question, it looks like it

Unless the government spends £140 billion or so