Robert Peston claimed yesterday that:

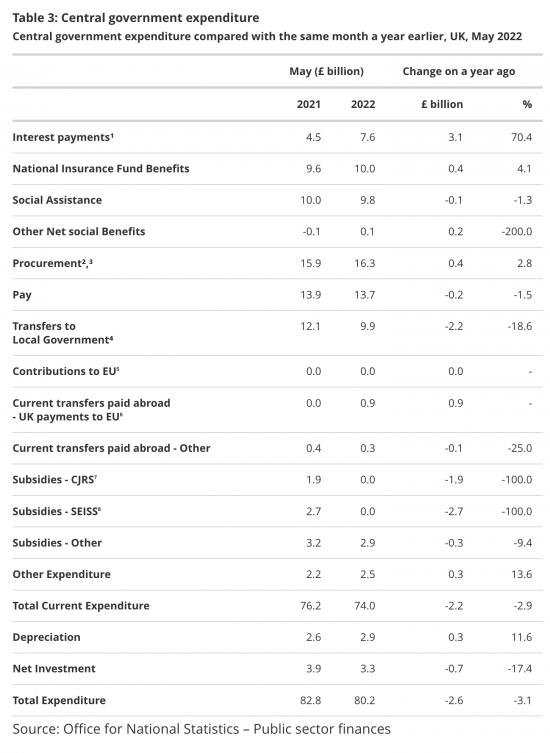

Like many journalists, Peston has a habit of misreading data. He has taken this data, published by the Office for National Statistics, with regard to the public finances in May at face value:

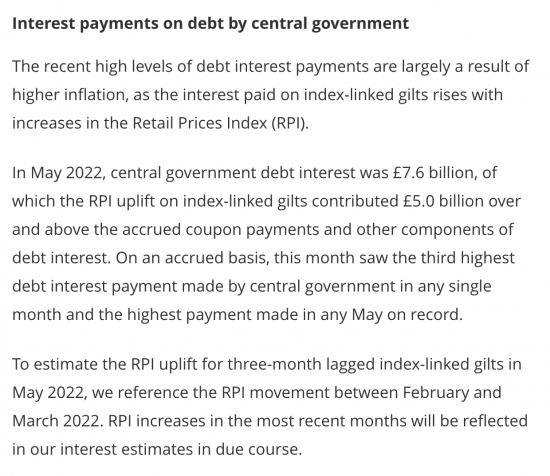

He panicked about that top line - and the 70.4% increase in interest costs. He really should not do so. The ONS added this explanation to this figure:

Put that in plain language and what they are saying is the real interest cost this month was not £7.6 billion. It was actually £5 billion less than that. It was really only £2.6 billion.

And for the record, last month they said that the cash cost was only £0.5 billion, although they recorded an expense that was £3.9 billion higher at £4.4 billion in all.

So, in that case the real interest cost to the government this year has been £3.1 billion and the Office for National Statistics say it is £8.9 billion more than that, making their total £12 billion for the year to date.

What it looks like is that the ONS is overstating the cost of government borrowing by more than £50 billion this year as a result, implying it could come to well over £70 billion in the year if we extrapolate these results when the cash cost may be less than £40 billion.

And to be clear, the Office for National Statistics is not alone in doing this. The Office for Budget Responsibility is forecasting an interest cost of £87 billion this year.

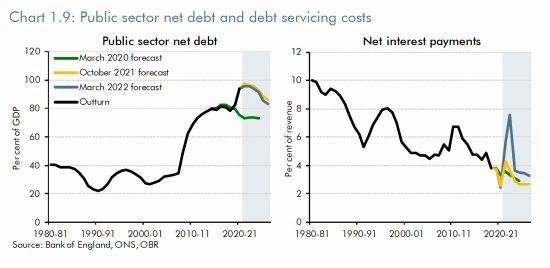

So how is this possible? What explains the freak expense? And I stress, according to the Office for Budget Responsibility they think it is a freak expense as this chart from their March forecasts shows:

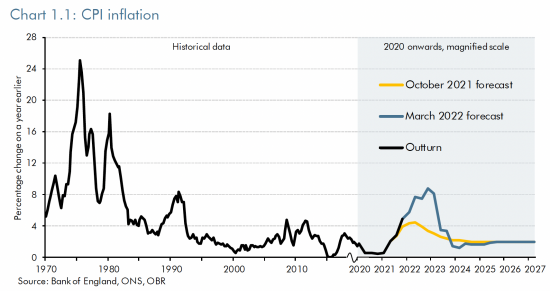

That right-hand chart is pretty clear: overall, they think interest costs in coming years are headed downwards. But I should add that this was their inflation forecast:

They were expecting inflation to reach around 9% later this year. We now know it is likely to be 11%. Then they expect it to fall, and to be clear, so do I, because the historical evidence is that this is what always happens.

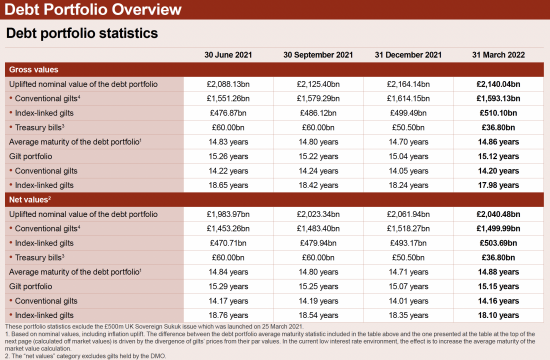

Why are these issues linked? That's because of the way that the UK gilt market (or government borrowing market) is structured. The UK Debt Management Office summarised this at the end of March as follows:

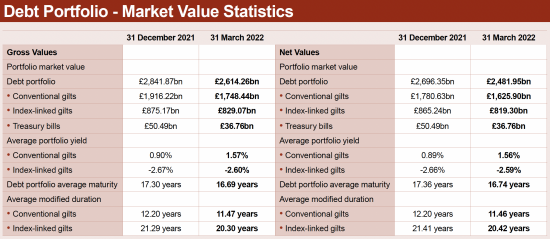

The market value of those bonds is a little different to their nominal value:

It is not hard to sport that it is index-linked bonds that are the issue when it comes to market values differing from nominal value. And let's be clear, the Office for National Statistics says that too.

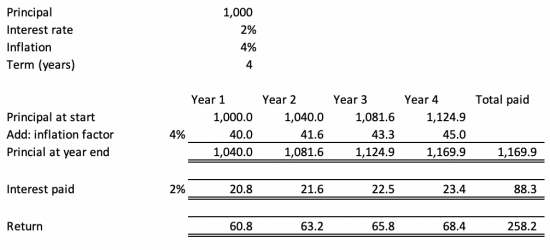

To explain this requires that the working of an index-linked bond be understood. When an index-linked bond is issued the person buying it puts a lump sum into that bond. Let's say it was £1,000. Let's assume that they keep it for the life of the bond. Let's assume that life is 4 years.

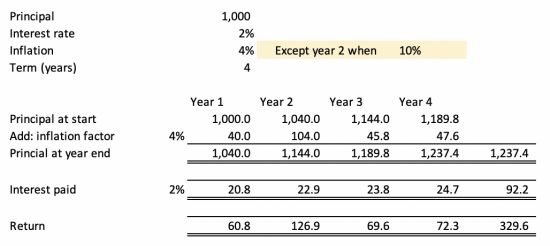

Now let's assume that the interest rate on the bond was set at 2% paid annually, and is fixed at that rate for the whole period (which is normal on these bonds). And let's assume that the principal value of the bond is updated for inflation throughout its life, as is normal, again. Let's assume that rate is 4% each year (unlikely, but it makes the numbers grow more quickly). The payments due in that case are:

The owner of this bond gets two returns. One is the interest. The rate is fixed. The amount on which it is paid is increased each year to reflect inflation. They get a little over £20 each year in interest as a result, as the table shows, with inflation literally inflatng this.

Then they get the inflation-adjusted capital back when the bond is redeemed. The capital has increased from £1,000 to £1,169.90 as a result of inflation. So they get this last sum back - an increase of £169.90. But they only get this when the bond is repaid.

Now let me throw in a twist. In year two assume that inflation is 10%. Now the table looks like this:

What you will notice is the apparently aberrational cost in the year when inflation increases. It's not that the interest cost changes much. What does happen is that the amount due on redemption increases. GGGGGGGGGGG

But let's be clear about this: it is not payable until the end of the term, which is four years in this case. There is little additional cash outflow in the current year, at all. And I stress, this is exactly what is happening now. Whatever the cost of the current inflation might be when it comes to index-linked binds, it is not going to fir for a long time. The Debt Management Offi8ce report shows the average life of index-linked bonds: depending on how estimated they are between 18 and 20 years on average, meaning this cost is not going to hit for that long.

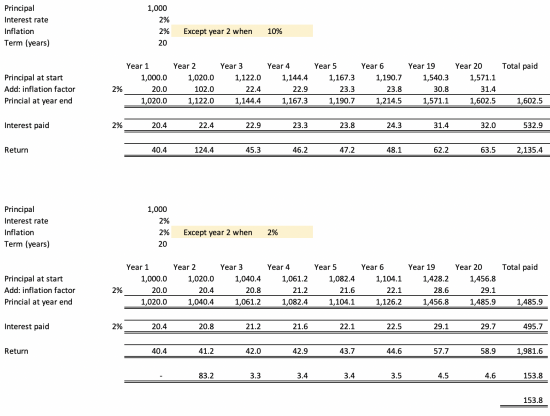

Now, I am not saying that just because a cost does not hit for twenty years it should be ignored. But, to explore what this means I reworked the above tables with a twenty year bond and just one year at 10% inflation and all others at the target 2%, which is much more like;ly than 4%:

For the sake of comparison, the bottom chart removes the inflation in year 2.

Both charts exclude a print for a number of interim years to get them on the screen: they are there in the data.

There is, as is apparent, an increase in interest costs over time: but this though only amounts to £37.2 (£532.9 - £495.7). Few would argue that these cannot be recognised as they happen. But the real change is the additional cost on redemption of £116.60 arising eighteen years after the inflation that gave rise to it, and which inflates the current value of index-linked bonds on the second-hand bond market now. How should this be accounted for?

There are two options. One is that this is an event now, requiring to be accounted for at this moment. That is the option the government is adopting. The other is to suggest that this is an event happening in maybe 18 years time which has to be accrued for between now and then in equal equivalent stages over that period.

Roughly speaking (and because I am talking about issues of principle here roughly speaking is good enough) this can either be shown as above, with a massive one-off boost in costs now and modest increases thereafter, or the interest can be paid as it accrues and the £116.60 additional cost of capital redemption can be spread over the 19 years it will take to accrue to payment, given that the payment day is that far away. My argument is that since the bond was designed to last until expiry (and they always do) then this cost accrues over 19 years at roughly £6 or so a year on top of the roughly £2 a year extra interest cost. So the increased cost is £8 (roughly) a year and there is no one-off cost of £83 now.

The government, however, is saying this is a cost now. But why? When issuing a twenty-year bond shouldn't the cost of settling it be averaged over its remaining life? My suggestion is a simple one: the government and ONS are offering accounting here that fails to tell an objective or politically appropriate story on interest costs to facilitate a crackdown on working people to deny them a pay rise now. And that is a political conspiracy using data that I think is wholly unjustified.

Peston has fallen for the ruse, and so have lots of others. But it is just that i.e.a ruse to make them think the government is heading for hell in a hand cast as a result of massive additional interest costs when on average these are not going to be paid for eighteen years.

It's time to stop falling for the accounting abuses and talk about reality. There is nothing about the current inflation that is stopping this government from affording pay rises. And that's a simple fact.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

There are links to this blog's glossary in the above post that explain technical terms used in it. Follow them for more explanations.

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

Buy me a coffee!

Buy me a coffee!

It is a very serious charge ‘ONS accounting not telling objective story’. You ought to challlenge ONS.

But so complicated.

Would be good if this could be summarised in a couple of sentences.

Havent read through full details, and pretty feeble at understanding accounts, but is – ‘they have overstated govt interest payments this year by falsely suggesting the full cost of settling twenty-year bonds occur in this year rather than being spead over the years of their remaining life’? …..a fair summary?

Summary fine

I have challenged them on this

Email exchanges happen quite often, to no avail

Richard wrote: “My argument is that since the bond was designed to last until expiry (and they always do) then this cost accrues over 19 years at roughly £6 or so a year on top of the roughly £2 a year extra interest cost.”

Agreed; that is the logical conclusion that most accountants would propose. However, the decision is being made for political purposes as Richard points out. This raises huge concerns about the quality and consistency of UK Gov accounting and the resultant data which derive from it. It’s now clear that we have a UK government which routinely lies and distorts facts, so how can any data, economic or otherwise, be trusted? Or perhaps that is the aim all along: to obfuscate for personal and political gain?

Out of interest, do the accounting records of all government departments now use accruals-based accounting, or do some still report on a cash-accounting basis? I vaguely recall that the Treasury was still reporting in the not too distant past on a cash basis (as did the NHS), which automatically resulted in timing differences when its data were collated with data of other departments.

We have a weird mix of cash and faux actual accounting

This is in the latter category – because it suits them

I wonder what benefit the players in this game (Treasury, ONS, UK Government Departments etc) imagine they are getting from an opaque methodology based on faux accounting? But then they’ve got previous: GERS is a classic example of widely circulated misleading data deriving from, in the main, estimates rather than actual data and masquerading as an accounting statement.

I have been in discussion with the ONS to0day, having asked a series of quite complex questions

They have agreed to discuss them and get back to me.

What accounting basis do the government or the ONS say they are using? If the government are booking all of the uplift in the value of the gilt when it happens, in year 2 in your examples, that is not an accruals basis. It looks like fair value.

It is whatever suits them

The only occasion when they get close to proper accpot8ing is in my opinion in the whole of government accounts

But you must also note I think fair value accpoti8ng another giant con trick

If they are answering the question “how much would we have to pay off the liability tomorrow” that is one thing. Can they repay whenever they want?

If instead they are measuring the cost of the liability to repay at the end and allocating that cost over the term, they can’t recognise the uplift in one period: they have to spread it over the remainder of the term.

I suppose an alternative would be to discount back the estimated liability to repay at maturity, but a lot would depend on the chosen discount rate, and they would still not recognise the uplift all in one go.

Agreed

Thank you so much for this. That is fascinating. It had occurred to me that the Debt Management Office is just about the most important executive agency of all, but its operations are so shrouded in obscurity and mystery, that it is hard to discern what influence it has over Treasury and Bank officials, and what influence Treasury and Bank officials have over it. It would also be useful to understand more about the DMO/ONS nexus. Is it an official tail which wags the ministerial dog, or has it been manipulated by ministers and Treasury officials, or both?

I have never seen any serious academic article describing its operations since its establishment 24 years’ ago, and nor have I seen any history of its operations (which I suppose are still subject to the 30 year rule), still less any pending academic work. In terms of the pre-1998 history, I have encountered only this: https://www.cambridge.org/gb/academic/subjects/economics/macroeconomics-and-monetary-economics/bank-england-and-government-debt-operations-gilt-edged-market-19281972?format=PB (which provides very useful insights into the reduction in war debts via ‘financial repression’), and in such incidental remarks set out in the Clapham, Sayers, Fforde, Capie and James histories of the Bank.

I appreciate that governments always want to reduce their funding costs, and that this has – for at least the last couple of centuries – been a primary objective of the Treasury. What I can’t make out is whether they really are genuinely frightened of a creditors’ strike, or whether they are simply trying to advertise to the gilt market that they are ‘serious’ about public debt, despite being only semi-serious, as part of a wider strategy to mollify the market and to reduce pressure on the exchange rate (and, with it, imported inflation). I cannot fathom their strategy, although I cannot also discount the possibility that it is part of a class war being waged on the part of their affluent supporters in London and SE England against the rest (but would that not be self-defeating electorally?).

It has struck some colleagues and me that this is an area well worth looking at

Down to the sham of the DMO supposedly being distinct from the Treasury of which it is just a part

This goes along with the apparent virtual absence of a substantive body of work on the Consolidated Fund and its operations (discussed here recently), in the economics canon. What on earth do economists actually spend their time doing that is in any way connected with the way the money system actually works?

As far as I can see no one asks

And I can tell you why – it will take some ingenue to get a journal to publish something so useful

Very few would – which is why it is required

Ingenues are rarely sufficiently ingenue in academia – to rock the boat.

True

We have a perfect example of the Johnson method in his C4 News interview with Krishnan Guru-Murthy . Presented with a catastrophic set of election defeats, he said he was not going to “minimise people’s feelings”, while he went on not just to minimise them, but dimiss them as just another standard mid-term by-election setback effecting all Governments. Johnson very precisely claims not to do exactly what he intends to do. It goes along with an “Oven ready Brexit”; that wasn’t ready, and a ropy oven, we can’t afford to switch on.

The people of Wakefield didn’t vote for Johnson in 2019, they voted for an Oven Ready Brexit, and they have finally woken up to the fact that they have been scammed by a political hustler. They will not long be alone in drawing that conclusion.

Correct

Let us hope they’ve seen through him.

There’s unfortunately always enough people who fail to do so, so fingers crossed.

Many thanks – very clear, and useful, since (like Peston) I hadn’t thought it through.

Possible literal in penultimate paragraph: “hell in a hand cast” – did you mean, “in a hand cart” ? (just in case you want to reproduce this.)

I’ll change

Taking your last worked example; additional interest charge now – £116.60p; my question is, what happens to the accounting entries, worked through and taken as a whole; because the Giltedge holder doesn’t receive the £166.60p now in his/her accounts; so, if I am following this through, where does it appear (or have I lost the thread somewhere)?

It appears as a mark to market adjustment in a rational market place

There are no rational market places, of course

The point I am trying to approach, is that following the current treatment the interest seems effectivelt to be shown as effectively both paid, and deferred (in the balance sheet), does it not? Or have I finally left orbit altogther?

Yes. You’re right. There is double counting…..

The uplift is counted as both “interest paid” AND increased principal owing.

A complete nonsense.

We had a long discussion on this a month ago ….. and I supect will have one every month until base effects bring inflation down.

Incidentally, you do need to collect a lot of the best of these national economic-accounting Blogs, and publish them together in a book on National Accounting.

With blooper corrections (I found a few)!

Time, John, time

“To explain this requires that the working of an index-linked bond be understood. ”

Indeed, this is important. Why then do you write a whole article where you don’t understand them?

“The owner of this bond gets two returns. One is the interest. The rate is fixed. The amount on which it is paid is increased each year to reflect inflation.”

The coupon payments on inflation linked bonds are also indexed, so your calculations and arguments are wrong.

Here is a link to how IL actually work:

https://www.dmo.gov.uk/media/1953/igcalc.pdf

“Index-linked gilts pay semi-annual cash flows indexed to the Retail Prices

Index (RPI). In practical terms this means that both the coupons and the

principal are adjusted to take account of accrued inflation since the gilt’s first

issue date. ”

So your arguments above are completely wrong. I think if you are going to write about a subject and make various claims, it is probably wise to understand the basics first.

Respectfully, that is exactly what my example shows

Respectfully, you are wrong and your example does not show this.

You are ignoring the inflation uplift for the bond coupons, which the DMO/ONS are not doing. You are treating the coupon as fixed, which it is not.

You can see this clearly in your example where you correctly inflate the notional of the bond, but then apply a nominal interest rate to the new notional. This is incorrect.

What you should have done (as detailed in the link I supplied) is apply the inflation uplift to the coupon as well.

The actual coupon is calculated as:

Current coupon = coupon on RPI base date x latest RPI index value/RPI index value on base date.

By not doing this you are missing a large part of the cost of inflation linked debt, so it is hardly surprising you get a far lower number than the DMO/ONS.

This rather large error then invalidates all you other claims about the accounting, which is correct as presented by the ONS, and everything that follows. I would suggest that if you are to make claims about the accounting for inflation linked bonds, you actually make sure you understand the first.

I am happy to be shown to be wrong, but my example does, I think match that of Pimco, for example, and they know about this stuff

And I am of course uplifting the coupon – which I based on the inflated notional

You appear to be double compounding. That is not how I read the DMO

BUT it makes no difference to the overall argument I am making, of course – rather proving you are trolling come what may

But, please prove that the bonds double compound and I will stand corrected

I don’t know where you are matching PIMCOs example, which you have not referenced elsewhere, but I doubt you match their example. They and everybody else make calculations on linkers as laid out by the DMO, which is the only correct manner.

You are not uplifting the coupon properly. What you are doing is uplifting the nominal face value of the bond and then applying a fixed coupon to that. Even that you aren’t doing totally correctly as you are applying an uplift based on a year on year increase, when in reality the uplift should be based on the change in the inflation index.

What happens in reality is that the coupon itself (the 2% in your example) is inflated by the index. You are just (improperly) inflating the face value of the bond and taking the coupon as 2% of that, which is wrong.

Both the coupon and nominal value of linkers are inflated. You are only doing the nominal value. This makes sense, as if you did not do this the coupons would quickly become irrelevant – which is exactly the mistake you have made and exactly why you are showing a much lower number for interest payments than the DMO/ONS.

If you think about it, the idea of an inflation linked bond is to maintain the same value of investment and returns in the face of inflation. So both the initial investment and the interest payments on it change over time with inflation to provide that protection.

With this in mind, it makes a massive difference to the argument you are making. Your claim is that the ONS are overstating interest payments and doing some for of accrual accounting for the increasing notionals of linkers.

This is not the case, because you initial claims about inflation linked bonds and how their interest payments are calculated are wrong. Following on from this, pretty much everything thereafter is also wrong as a result.

To make it very clear:

Interest payments have increased to levels the ONS are stating. These are just the semi-annual coupons paid as usual. The increase is down to inflation alone and there is no accrual of redemption value within this figure.

The ONS are accounting correctly and the arguments you are making are simply incorrect, because of the basic error you have made as you do not know how inflation linked bonds work in reality – instead using your own version which differs greatly from reality.

Mitesh

Respectfully, I have increased the returns

And you have appeared out of nowhere to say I am wrong when those who I know have been in the industry for a long time say I am right. Who to believe? It’s j0pt hard, is it?

And what you very clearly show is that you have not a clue about what the ONS are saying – and you most certainly could not possibly link their accounting provision to your argument and anyone who says they can clearly does not understand ILBs in aggregate, or accounting, or both

So, politely, I wouldn’t waste your time again

Richard

PS It would have really helped your case if you had not, whether you know it or not, revealed some other classic indicators of trolling activity.

The link is to Treasury DMO: https://dmo.gov.uk/data/gilt-market/index-linked-gilts/

Then click on ‘Method for calculating cash flows on index-linked gilts’, which is where the DMO quote comes from. Scroll down, and an example is given which Mitesh did not provide.

On interest payments, the DMO paper is: “The rate of interest for each payment is determined by taking the annual coupon quoted in the title of the bond (e.g. 21⁄2% Index-linked Treasury Stock 2020) and applying an adjustment to take account of the movement in the RPI. The coupon element is fixed while the RPI adjustment varies from payment to payment, as described below. The resulting rate of interest, when applied to the nominal amount of the bond held, gives the amount of interest to be paid.”

The example is here (The brackets do not ‘cut & paste’ properly, but I have adjusted to ensure keeping the calculation effects the same):

For example, the Base RPI figure for 41⁄8% Index-linked Treasury Stock 2030 (first issued in June 1992) is 135.1 – the RPI figure for October 1991 (published in November 1991). This gilt pays interest in January and July for which the relevant RPI figures are those relating to the previous May and November respectively. So, the rate of interest for the payment in January 1998 was calculated as:

4.125/2 × RPI for May 199/RPI for Oct 1991

For a holding of £10 million nominal of this bond the coupon payment would have been:

(4.125 RPI /2) x (RPI for May 1997/RPI for Oct 1991), rounded down to 4 decimal places, then multiplied by

£10,000,000/100 = 4.125/2 × 156.9/135.9 = £2.3953 (when rounded down to 4 decimal places)

multiplied by £10,000,000/100 = £239,530.00

Redemption payment:

Similarly, the redemption proceeds on maturity in July 2030 per £100 nominal of this bond will be:

£100 × RPI for Nov 2029/RPI for Oct 1991 (which will be rounded down to 4 decimal places)

Thanks John

But note they apply a variable rate to a fixed nominal coupon

For ease of example I am aware I deliberately didn’t the other way round

The net difference is, I think, immaterial for the skeins argument

What does not happen is that both are compounded

Allow me to focus on the interest element. There may not be a material difference (I hesitated over the trickiness of doing a simplified comparison), but it does seem they are applying a double component; inflating both interest (saying it is fixed, but inflating the effect) and to the principal. For example the DMO says: “The coupon element is fixed while the RPI adjustment varies from payment to payment, as described below. The resulting rate of interest, when applied to the nominal amount of the bond held, gives the amount of interest to be paid” (4.125/2 × RPI for May 1997/RPI for Oct 1991).

From your first ‘year 2’ simplified example calculation, (2% fixed interest on £1,122 capital (inflation uplifted year 2 by 10%) = 2% x £1,122 = £22.4. But as written by DMO this is 2% adjusted RPI increase for the period (year 2 in the example): which I take to be 10% x 110/100 x £1,122 = 2.2% x £1,122 + £24.68. As I read it, the additional £2.24 interest is actually paid: “the rate of interest for the payment in January 1998” i.e., “for the payment”.

Notice that this sudden fivefold increase in interest increases the payment by 10%. The bigger point is that the interest payments actually recorded for inflation adjusted gilt-edged, was up from £4.5BN to £7.6BN, an increase of 68.9% for what appears a lower rate of increase, so this implies the major component is the deferred, inflated principal increase.

I offer this not as a certainty, but as an effort to understand what is going on.

I am out all day today so can it look now

But this does not in any material way change my argument

Trust me, Richard is correct on this.

I used to trade this stuff for a living and (bar a few non-substantive, simplifying assuptions) Richard is correct.

Mitesh – if you think Richard has this wrong, please can you provide your own calculations for Richard’s examples.

For example, what would the amounts look like for £1000 of a 2% index linked 4 year bond, with inflation running at 4% except for 10% in year two? Or £1000 of a 2% index linked 20 year bond, with inflation running at 2% except for 10% in year two?

The DMO example applies an indexed interest rate to a fixed principal. Richard applies a fixed interest rate to an indexed principal. It is the same result – (fixed principal) times (index) times (fixed rate). Multiplication is associative, so you can multiply either the rate or the principal by the index first. You don’t index both.

Given the redemption amount increases by the index too, it seems to me more natural to consider the principal being inflated up, but you can do it the other way if you wish. The numbers should end up the same – but can you show us they are not?

You seem to think as I do Andrew

Mitesh would seem to like double compounding

“There are two options. One is that this is an event now, requiring to be accounted for at this moment. That is the option the government is adopting. The other is to suggest that this is an event happening in maybe 18 years time which has to be accrued for between now and then in equal equivalent stages over that period….The higher capital repayment from RPI indexed bonds should not be assigned to this year. Instead, it should be discounted over time until redemption.”

That odd as in the past you have said that discounting the future is the work of the very devil.

Even then your calculation doesn’t work. Because if we do as you say, allocate over years to redemption, then where in the accounts are the allocations for this year from past inflation? The current accounting method means those increases are all allocated in past year accounts. Your chosen method would mean that this year’s accounts should have some portion of past inflation in them..total nonsense..

Heaven’s above that accounts might reflect the impact of psst events

If you really are an accountant that is a pretty crass comment

Thanks for such a full explanation. For me it is crystal clear that the RPI uplift is not interest but an increase in debt outstanding.

I would also add that government income from tax is largely inflation linked so the increase in the amount outstanding should not concern us unduly either.

More to the point, do the figures take into account that the buyers paid more than the face value, sometimes a lot more for the stock when it was first issued?

No: let’s keep it reasonably simple

I have to say that in the case of Mitesh, Richard is right – his hasty reversion to insults rather than talking though perspectives is always a dead giveaway in terms of trolling.

It was a gratuitous insult; nevertheless we should focus on the issue. I think there is, prima facie (I say no more), an issue over interest. See my basic example applied to richard’s calculation. There seems to be double counting, but it also seems to be paid (not deferred). As I pointed out, this does not explain the degree of uplift to UK DEbt interest uplift; which (again, prima facie) seesm to rely on expensing off, unpaid deferred inflation uplift that is not paid. So there is a point to examine, but it doesn’t change the thrust of richard’s bigger argument. I ask people to examine the facts.

I may be wrong. So, prove me wrong. I really don’t mind, because for me we on;ly move forward by an iterative process of making mistakes, moving forward and understanding better.

I t is not a matter of taking sides, and I am disappointed that Mitesh approached the issue in that belligerent way.

I always said I was happy to be proved wrong

I would check but I am out all day

Sorry, John, but I don’t agree. The DMO example has three elements –

* the fixed interest rate (4.125% in their case)

* the RPI adjustment (from issue to the payment date: May 1997/Oct 1991 in their case, that is 156.9/135.1)

* the fixed nominal amount (£10m in their case)

To pick one of Richard’s examples

* fixed interest (2%)

* RPI adjustment (2% in year one plus 10% in year two is (1.02*1.10) = 1.122 or 12.2%)

* the fixed nominal amount (£1000)

So the 2% interest for year two is 2% * 1.122 * 1000 = 22.44

You can consider that as a 2% rate applied to an inflated principal of £1122 (which is the amount that would be paid on redemption at year two). Or as a 2.244% return applied to a fixed principal of £1000.

That said, I may be missing something…

I still read it the way you do

Others do as well, Pimco for example

Thank you Andrew. You make a good point. Because in trying to apply a comparison of DMO methodology to Richard’s example, I followed the inflated principal of £1,122 (and then applied the inflated interest of 2.244% – which is indeed double counting) but in fact it should be the fixed principal of £1,000, as in the DMO paper. This brings us back to Richard’s calculation, as far as I cans see – applying the DMO rules of calculation: QED? Unless I have missed something.

I think we can say that the example confirms that the DMO determines that the principal remains fixed, and therefore the interest is inflated; but as you point out, the effect remains the same.

It seems then from the DMO paper, increases in interest costs actually paid do arise, but as Richard argued from the beginning these increases are, in the context of payments actually made, modest. The problem of instant cash accounting for long term deferral (which, after all is the purpose of a bond for the issuer) appears to remain; unless someone has something to add?

I chose the easiest way to show what I thought was the outcome that fitted the DMO description

I think we have all arrived back there

Thanks

Oh, sure, the interest cost (the coupon actually paid every six months) does change from period to period, and Richard’s examples show that happening – otherwise it would be 2% on £1000 throughout the term.

The real problem is booking the whole of an increase in the redemption amount as “interest cost” in the period when it arises, when the bond might not be repaid for another 10, 20, 30 years. Can anyone suggest when (and why) that might be an appropriate thing to do?

A second issue will be accounting for the unwinding of a premium paid on issue, as these things are rarely issued at par.

Here is the first example I found from Google: https://www.reuters.com/markets/europe/uk-sells-new-2073-index-linked-gilt-with-record-low-volume-2021-11-23/

A 50 year index linked gilt due 2073, bearing 0.125% interest, issued in November 2021 with a nominal amount of £1.1 billion. And sold for £3.9 billion. So what do we do with the £2.8 billion premium? (What actually happens in practice: is it recognised in one go? Does it disappear into a hole? )

We could accrue “cost” of minus £56 million per year for 50 years, or something calculated by NPV and an implied discount (less in early years, more in later years) . And then of course accounting for inflation uplift of the redemption amount on the same basis each period, and spreading over the remaining term.

This is thev3xokanayion fir the negative returns still being reported on these bonds by the DMO

I have explored this as yet

And I will not be today, yet. I am on a university taxi run: the last one for this son. Results next week.

I’m not familiar with the workings of Index Linked Bonds and, in attempting to understand the possibilities being discussed, I’ve reduced it to what I hope is simple logic: The total face value of the bonds purchased is the capital and the interest paid on the due dates is simply that – the interest. Surely, if the bonds are index-linked, the PRI adjustment is made to the capital value and the interest paid on the due dates is calculated on that adjusted capital value, but at the interest rate initially set at the outset. That provides consistency of interest payments across the duration of the bond on a moving capital value reflecting changes in RPI. Any other basis seems illogical to me, or have I misunderstood the various arguments?

All the examples discussed above have assumed increasing rates of inflation, but if RPI rates were to fall, I’d expect the “principal & interest” logic to be maintained with reducing interest payments. But what happens if we have deflation rather than inflation – would the interest become a negative sum and reduce the capital sum repayable to the investor at maturity?

Ken

It is an interesting idea but we have avoided deflation for a century

I am not sure planning will have been done for it

Richard

“The real problem is booking the whole of an increase in the redemption amount as “interest cost” in the period when it arises, when the bond might not be repaid for another 10, 20, 30 years. Can anyone suggest when (and why) that might be an appropriate thing to do?”

Once we have set aside the “interest” calculation issue, which now seems clearer; this is surely, precisely the nature of the problem. As Mr Parry observed, there was a discussion about this on a thread some time ago, but at the time both interest and redemption issues were not clear and perhaps entangled. “Interest” seems now to have been resolved.

The treatment adopted on “redemption” payments seems to follow rules that are opaque, and difficult to understand. The desire seems both to defer, and at the same time treat some aspects as “paid”, but not actually paid. Since the whole purpose of a bond is to defer a promise to pay this opaqueness requires thorough explanation.

I will be talking to the ONS and maybe DMO

“which I take to be 10% x 110/100 x £1,122 = 2.2% x £1,122 = £24.68.”

Cannot stop blundering with typos (= not +)

Ken, take care to distinguish between RPI (Price LEVEL) and change in RPI (inflation). If RPI falls interest payments (and principal repayable) would decline although they can’t fall below the level at which the bond was first issued (for most but not all IL gilts). Falls in RPI are very rare and, for practical purposes can be ignored.

Your key point is important…. the RPI uplift can either be counted as interest paid OR increased principal owing…. but not both. To me it is clearly best considered as an increase in principal owed.

Agreed

The key point for me is the entirely misleading picture that the ONS gives when it issue a press release saying “Record high interest paid on government debt in May 2022” and mentioning “a £3.1 billion year-on-year increase in debt interest payments”, backed by figures that show “interest payments” increasing by 70% from £4.5 billion in May 2021 to £7.6 billion in May 2022.

https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/economicoutputandproductivity/output/articles/ukeconomylatest/2021-01-25#publicfinance

Paid. Payment. Expenditure. Cost.

That is parroted by many in the media with no understanding that these are amounts that won’t be paid for many years, if at all. eg

* https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/ons-gdp-inflation-holly-williams-office-for-budget-responsibility-b2107476.html

* https://www.bbc.com/news/business-61906235

* https://www.theguardian.com/business/2022/jun/23/uk-borrowed-14bn-may-inflation-interest-debt

Did the government actually “pay” interest of £7.6 billion on May 2022? No. Did anyone receive it? No. “In May 2022, central government debt interest was £7.6 billion, of which the RPI uplift on index-linked gilts contributed £5.0 billion over and above the accrued coupon payments and other components of debt interest.”

So how much of that £5.0 billion of “RPI uplift on index-linked gilts” was actually paid out to bond holder in May 2022? Almost nil. When will it be paid? In most cases, not for many years.

So how much interest was actually “paid”? Only £2,6 billion?

Not to put to fine a point on it, to label the higher number a “payment” is simply a lie.

Precisely

And my whole point….

“Did the government actually “pay” interest of £7.6 billion on May 2022? No. Did anyone receive it? No. “In May 2022, central government debt interest was £7.6 billion, of which the RPI uplift on index-linked gilts contributed £5.0 billion over and above the accrued coupon payments and other components of debt interest.”

This was where I started. My only slight difference from Andrew is that I wish to focus on understanding, and establishing in the public domain, what precisely the ONS and DMO have to say about what they are doing, and how they justify it in accounting terms. This means they require to present: 1) the precise principles of accounting they are following, in detail* how they apply them; 2) why inflation due on bond redemption is not deferred until payment due (cash accounting), or spread over the outstanding years from the period it arise to the date of redemption? 3) How much (if any) of the £7.6Bn applies to inflation applicable to the principal, not due until redemption.

* At least the same detail as offered in the worked interest example in the DMO paper.

I forgot to add that the ONS and DMO need to explain whether thay are using the term “paid” or “payment” in two different ways; one which means the holder of the stock has actually received a payment; or one which means “paid”; but no actual payment has been made.

Agreed

I will be drafting a request

Thanks Clive. You wrote “To me it is clearly best considered as an increase in principal owed” and I agree that makes more sense: the interest paid throughout will reflect the changing book value of the capital. In addition, during its lifetime, the capital value will fluctuate according to movements in the bond market, but these are transitory trading fluctuations which (with my long-out-of-date accountant’s hat on) shouldn’t affect the book value until realised by a sale, when they get booked as a profit or loss as compared with the PRI adjusted book value of the capital at date of sale. On redemption I’m assuming that the capital as adjusted for RPI to redemption date and interest calculated thereon in the normal way, are repaid to the bond holder.

But does the market value at redemption date get reflected in any way in the repayment if it differs from the revised value of the capital as adjusted for RPI? My logic assumes not: if the bondholder hasn’t been astute enough to sell the bond when market values are at the top end, that’s surely his/her tough luck? If the market value is lower than the final book value, the bond holder wins a watch as the bond is guaranteed at least its book value as adjusted for inflation over its duration. And that’s what people in your job get paid to advise on.

At redemption MV = redemption value

The problem is in between

The firm of accounting used makes almost no sense under any accounting rules.

I will be asking for clarification

The market value (what a buyer would be willing to pay, and what a seller would be willing to accept) will vary during the term, based on rational expectations of the future cash flows (the biannual coupons, and the redemption amount) and economic conditions (particularly the base interest rate, and expectations about inflation), but as the bond approaches maturity, the market value should approach the redemption amount. If you are expecting £1000 tomorrow (or next week, or next month) you might pay a shade less than £1000 today. The redemption amount will be governed by the terms of the bond itself.

If an investor bought the bond at a premium over its adjusted par value, they might make a loss. But perhaps they have just got what they wanted, which is a secure cashflow linked to inflation.

As an investor, when I look at my portfolio over any period I care about two thing; the cash income received over the period and the change in market value of the portfolio over the period. That’s all (more or less).

The government position is the mirror image; how much cash have they paid out and what is the change in market value of the gilts in issue.

If we want more detail then we could break down the change in market value by (a) government deficit financed by net new issuance (b) RPI uplift on the principal amount of I/L Gilts outstanding and (c) market yields.

Not complicated. I really don’t see any other sensible way to look at this (although it does throw up some anti intuitive wrinkles that I will save for another day).