Yesterday John Warren posted a thought experiment on the blog. Following an introduction that is worth reading but which I will not repeat here he said:

Here is the thought experiment, and the question. It is very simple. What would happen if the Government decided to print £1Trn of crisp new notes in all the denominations; but – crucially – didn't circulate it: just placed it in the (empty and convenient) vaults in Threadneedle Street; the fiat equivalent of Gold. How would that appear in the accounts of government and BofE, and what happens to the recording of the National Debt. How does the balance sheet look now? We could vary the terms; print a single £1Trn bank-note, then we know it will never circulate (that variant was put to me by a young economist – who has broken free from the conventional wisdom).

My immediate thought is that this is a variant on the trillion-dollar coin suggestion from Krugman and others in the USA. I think the variant is really important, including in this case. There are two reasons for that.

First, technically £1 trillion of banknotes not issued do not represent debt: they are simply a prepaid cost of the manufacture of tokens of debt that might be issued. As such the double entry is credit manufacturing cost in the income account, debit stock and work in progress on the Bank of England balance sheet, with that debt retaining value until the note design ceases to be used, when this stock will become worthless. I suggest that the printing has no consequence at all until issued simply because there is no liability on the balance sheet. And that is important: what it says is that the Bank of England is, like any bank, unable to create money without third-party involvement [see footnote].

However, the Treasury can and does creates coins with value when minted through its subsidiary the Royal Mint and I think it can be successfully argued that they are not in the official money supply figures, although acknowledged by the Bank of England as base currency. This is because coin (and there are only £4.2 billion worth in existence) are not accounted for as liabilities whilst in contrast notes most definitely are in the national debt, if only via the Bank of England net contribution to that debt. I should add that I have tried to get straight answers on both these issues from HM Treasury, the BoE, and ONS, without any success from any of them. But, the evidence from the accounting is I think unambiguously what I have suggested.

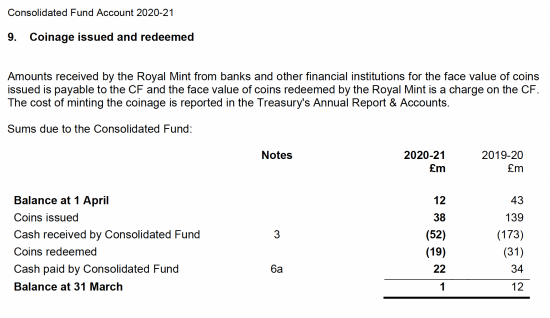

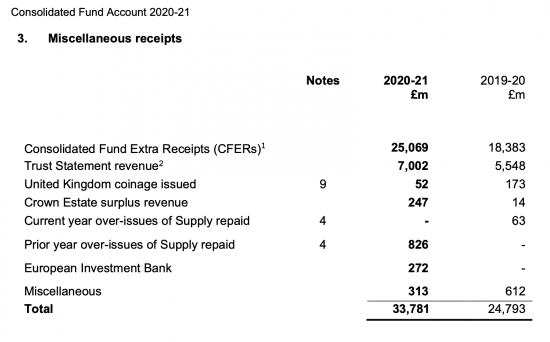

I should, having said so, make clear that how the Treasury accounts for the surplus / loss on coin creation is unclear in its accounts, largely because after routine manufacturing costs for the current coins in issue the net sum might be very small, but the accounting for their issue can, for those willing to pursue the point, be found in the Consolidated Fund Accounts. This is from them for 2021:

The essential point here is that the value of the coins issued were income in the Consolidated Fund:

There is therefore a debt with the Bank of England - the Consolidated fund balance increased.

But where, after costs of issue, does the profit in the Treasury go? A credit in the income statement has to have a balance sheet consequence after all. There is no indication I can find of that: the net sum is probably too small to require disclosure, in fairness (and to confuse matters the cost of creating the money is confusingly in the Treasury's accounts). And yet this is the age-old seignorage - the profit that goes to the coin creator from turning metal into coin, and it does exist. It would most definitely exist if a £1 trillion coin was created.

As noted above, the value of that coin would be recorded as income in the Consolidated Fund - which is a trust account of the Treasury, and so part of government funding. Base money would increase by £1 trillion as a result. But where does that £1 trillion credit in the income statement of the consolidated fund flow to on the balance sheet? It can't go to liabilities because there is already a credit in the income statement, so the only place it can go is to the Reserves of HM Treasury. And meanwhile, the Bank of England would simply record it as a banking transaction.

So what does an increase in reserves mean? It is, in effect, an increase in capital, which is, of course, exactly what happens here. The government did create capital for the banking system to use. The resulting accounting for such a coin reflects reality, which the accounting for QE and central bank reserve accounting does not.

The additional interesting point is that as far as I can see this gain does not fall out on consolidation of the accounts. When that takes place there is a debit left from the Bank of England accounts, which is to base money, and a credit to government reserves. I will happily be shown to be wrong. But in the time I have had available that appears to be the accounting result of this.

What is the consequence? My suggestion is that it is pretty straightforward. That debit to base money can be used. How? To replace the central bank reserve accounts held by the commercial banks with the Bank of England, I suggest. The coin might need to be broken down into some smaller units in that case starting with ten million-pound coins and maybe moving up to some billion-pound ones. But the point is, the Bank of England could insist that the commercial banks enter into an exchange of their central bank reserve accounts for coins to the extent that the Bank of England desired, and those coins would then be an asset on the commercial bank balance sheets guaranteeing their solvency, and permitting inter-bank settlement as well by registering charges on them, but at the same time no interest need be paid on them by the Bank of England. That last issue goes away.

And what of that credit in the reserves of the Whole of Government Accounts? That is then properly described as the 'national capital'. That is, it is the value injected by the government into the economy for the public good. But what the government does not have to do is then pay anyone for the privilege of having done the right thing for society.

Finally, does this prevent monetary policy using changing interest rates to be transmitted into the economy via the CBRAs? It does not. Remember, this worked in 2008 when the balances were around £40 billion. Near enough £900 billion is not required for this purpose now. Maybe £100 billion would be sufficient for that reason. It is hard to imagine more than £200 billion is required. Interest on all the excess is saved. That's quite something in terms of economic justice, and all for issuing some coins.

So is this the Krugman trick? I suggest not. That was intended to cancel debt. This does not. It recognises QE cancelled gilts and redenominates the central bank reserve accounts, for sure, but the aim is different. The aim is to cancel interest payments and to recognise capital. I don't see that as the Krugman goal, and suggest this is in any case better as it reflects what actually happens, simply repricing it.

[Footnote] This is also true with quantitative easing: the idea that a Bank of England subsidiary is the counterparty to Bank of England money creation in quantitative easing is not true. The Bank of England's Asset Purchase Facility is in fact run by a subsidiary wholly under the economic control of the Treasury, which underwrites all its losses. That is why it is not consolidated in the Bank of England accounts. although this is not admitted.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

Modern banking came into existence at the same time as the Phlogiston theory of Chemistry.

The Phlogiston explanation of combustion was proved to be radically incorrect over two hundred years ago. Unfortunately the three hundred year old theories of Banking have proved so beneficial to the owners of Banks that they still dominate our modern world. That is of course until Banks go bust when the owners drop all the old nonsense about Markets representing an inviolable natural law and demand government hand-outs.

Well, I hoped the thought experiment might start a chain reaction, but this has far surpassed my hopes. You have spun out ideas in different illuminating directions. I shall have to think all this through.

It is the logic of the accounting entries that are at the heart of this; as I thought. I hope the economists are all taking notes. I especially hope we may see some real response from the Treasury, BofE and ONS to your pertinent enquiries.

Many thanks Richard, I am quite ‘bowled over’.

I lost much of my Sunday afternoon and evening to that…chasing entries through accounts

But I did enjoy it!

I was going to ask a question about your comment on the “Sunak’s choice:… ” thread namely:

“Sure – they use bank base rate as a signal I know that

“See a reply coming to Clive Parry, who really knows this stuff

“So, you designate £100bn as CBRAs and the rest as QE reserves at 0.1% or even less

“Problem solved”

I was going to ask how we distinguish between the CBRA and QE reserves. I assume that would entail commercial banks having two accounts with the BoE and inter bank payments being only possible between accounts of the same type.

What you have described here would require the banks to buy coins with what would have been designated QE reserves. This neatly solves the problem. Also, because the coins would not be called debt, no one would argue that the government would have a moral duty to pay interest on it.

There is no difference

I am simply saying the BoE decides what part it wants to pay interest on

Rather like all banks decide what accounts they want to offer

I can’t say I am able to follow all your detective work in the accounts (my deficiency not yours) but the thought experiment is consistent with the analogy I have come up in my mind with for the reserve accounts as being like the cash “float” needed to operate a charity stall.

Without a float it would be difficult to conduct cash sales, but the money isn’t part of the sales and there is no net inflow or outflow.

While the interest issue doesn’t quite work with the analogy, you could imagine having to have withdrawn the cash from a building society account to provide the float. In which case you have foregone any interest available, there is no reason for it to earn interest while it is working for you in a different way.

Or have i misunderstood things (again)?

Not a bad one

Nice thinking.

Whilst the devil is always in the detail I love a comment I read several years ago on this subject. Was along the lines of;

“Good forbid that we have the rules of double entry book keeping broken”

There is however, use in trying to square this circle if only to keep the naysayers and book keepers at the BoE happy.

It made me think of gold reserves. Periodically Conservatives berate Gordon Brown for ‘selling our gold when the prices were low”. I knew we had some in the B of E as I saw a picture of the Queen in the vaults a few years ago. ( Why an earth was she there?)

But I came across this story on he Bank’s website. Thought it might raise a smile.

n 1836, the Directors of the Bank of England received anonymous letters. The writer claimed to have access to their gold, and offered to meet them in the gold vault at an hour of their choosing.

The Directors were finally persuaded to gather one night in the vault. At the agreed hour a noise was heard from beneath the floor and a man popped up through some of the floor boards.

The man was a sewerman who, during repair work, had discovered an old drain that ran immediately under the gold vault.

After the initial shock, a stock take revealed that he hadn’t taken any gold. For his honesty, the Bank of England rewarded him with a gift of £800. This would be worth about £90,000 in today’s money

I am sure there is a moral to be drawn here but I can’t think of one at the moment.

Bizarre!

Beppo Grillo(leader of the Italian 5 star movement) used to do some very astute observational comedy on the global financial system. He used to joke about gold. Saying it was the most polluting form of creating a wealth asset. In effect we dig some gold out of a hole in the ground….only to move it and bury it in another hold in the ground under a bank!! So why don’t we just cut out the destructive middle man and just build the bank on top of the gold!!

Truth is is we don’t need that gold at all , we can produce our own wealth asset via double entry book keeping and fiat money. Something the Nixon regime realised in the 1970’s when they abandoned the linking of the US dollar to gold and allowed it to float against global currencies. Your currency is only as good as your economy.

Very good

Doesn’t this indicate that because the Treasury and not the BoE is in charge of issuing coins from the Royal Mint, coins, large or small, are the equivalent of the Bradbury pound?

I was trying to get the government to admit as much – not so far successfully – here:

http://www.progressivepulse.org/economics/treasury-obscurantism-is-flourishing

In effect Treasury issuance finances the real economy whereas money produced via central banks always finances the bankers either exclusively or sometimes as well…

A neat twist ….

Well, this is really interesting. The letter to Ben Bradshaw MP from the Treasury (dated 17th May, 2022 – so hot off the press), if I can read the teeny-weeny print, states this: “the creation of new notes is PSND [Public Sector Net Debt] neutral, and therefore the creation of money does not contribute to the national debt”.

Did I transcribe that correctly? The only definition of ‘money’ offered is “(physical and electronic) money”, which then seems to become ‘notes’. To coin a phrase: curiouser and curiouser.

Can I add that there is a follow up letter in the Treasury right now seeking an answer to some related issues – so it will be interesting to see what happens with that one

Great! Your Blog is a wonder, Richard.

I try…

I am still reflecting on your detailed appraisal of the accounting for coin; but note that the lack of detail and transparency in the official information, which your review reveals, still leaves us short of a full explanation. How do we flush out an opinion (or better still the T-accounts from the Treasury, BofE and ONS – if the last actually knows)? I confess that when I was thinking about this issue I did not adequately distinguish conceptually between notes and coin; indeed I read note 8, Coinage issued and redeemed, Consolidated Funds Accounts and simply did not draw the appropriate implications. We are much the better for your critical examination of the available facts.

On ‘notes’ I accept the distinction you made with coin, and it fits with the history of coin, and the later derivative innovation of notes; but the distinction surely does not reconcile with the nature of a fiat currency, and perhaps only ever made sense because monetary authorities (the sovereign) effectively conflated the needs of a (universal formal measure) of currency (originally coinage) in foreign trade (using a commonly acceptable high value commodity – typically gold or silver – in other jurisdictions); with the absolute power over the domestic currency provided by the currency issuing authority of the sovereign (backed by the exclusive ability to tax the coin user, and enforce the coins use, and protect its value through draconian laws – including the death penalty, savagely applied). I will not rehearse here the full range of problems; but high value commodity coinage carried with it a serious, endemic plague of counterfeiting, clipping and other frauds that undermined the security of the coinage over the longue durée, and hence the monetary credibility of the sovereign (crises that came to a head in the later 17th century – 1672 Exchequer crisis, re-coinage etc). At the same time, in the domestic economy real economic activity among ordinary people had long been held back by the scarcity of coinage; which, of course depended on supply of high value commodities, which in turn created problems for low denomination coins; a driver of everyday economic activity for most people. Parliament in England reported, even in the late middle ages, the reliance of the mass of people on unofficial tokens, or even on foreign (Scottish) low denomination coins, so scarce was the low denomination coinage which most people would require in England to undertake transactions (in Scotland payment ‘in kind’ was generally prevalent, even in the mid-18th century). This may indeed have imbued ‘coinage’ with a special significance in the system, but it is illusory, and presumably could still be laid to rest.

It is slightly absurd to suggest coin, of course

And I stress, I presume these coins would never leave the BoE: they would;d simply have claims made on them

But the point is to say that the state alone can create coin with seignorage – the credit being a profit and not a liability as such

Thgis fits high up the hieracrchy of money – indeed at the top, I might suggest now

Might it be the case that there are different types of money according to use and/or B. o E and/or Treasury submerged/hidden classifications and that the clear differentiation of them is obscured so that it is easier to frighten/groom the citizenry into accepting « austerities » and the like?

There are hierarchies of money – as John Warren refers to

Base money is higher in the pecking order than commercial money

I need to build that into explanations

It has been good see the concept of ‘base money’ (M0) return to the debate once more I have to say.

And how………….

#mintthecoin

https://mintthecoin.org/

After reading this I went away and wrapped my head in a cold towel – I must say, I was confused. I am afraid I don’t see money in “accounting” terms – rather more in “plumbing terms”. The “coin” thought experiment does get one thinking but….

First, why is there an objection to paying interest on reserves? – It rewards banks for doing nothing useful.

Second, why does the BoE want to pay interest on reserves? – to transmit (tighter) interest rate policy into the financial and real economy.

At a time of hardship (or any time) it’s wrong to be handing out money like this to banks unless there is a real reason but effective transmission of monetary policy choices is an important issue. Can we achieve both objectives?

If a large client deposits money with a bank overnight it is virtually worthless to that bank. Nobody wants to borrow overnight and liquidity rules (introduced after 2008) mean that lending that money for longer can’t be done easily. (Retail deposits DO have some value… but a story for another day). In practice, banks discourage deposits and if they get them the only asset they get against that liability is Reserves at the BoE. So, in a world where there are excess reserves in the system the overnight rate in the market will always be very close to the rate paid by the BoE on reserves.

So, if we want the overnight rate to be higher (and that is the assumption here, that we do want higher rates) we could

(1) Increase the reserves required to be held by banks….. and pay no interest on them (this might take care of £200bn Richard suggests)

(2) Drain money by raising taxes

(3) Drain money by selling gilts

(4) Mandate that all bank deposits carry interest at a rate linked to (but below) the policy rate. (Remember, banks have (almost) no money of their own – is is always “other people’s money” and the economics of banking depends on the SPREAD between the rate the bank borrows at and the rate that they lend at – NOT the absolute level of rates. Of course, the absolute level of rates does have an impact on the spread a bank can earn… but it is the spread that matters.)

(5) there may be others

(1) Simple to do. Definitely should be done

(2) No. Totally wrong at present

(3) Simple to do. Should be done in combination with (1) in order to manage interest rates across all maturities

(4) Could be done… but what the banks don’t get in extra profit will now go to savers. Is that what we want?

(5) Yes, there is room for more imagination here. Perhaps we need a different way to tax banks to reflect their special position in the economy?

Noted

My thought experiment was to suggest ways to really address this

I think coins could work

But they are an artifice. There are better solutions if politicians dare think them.

I proposed the thought experiment in order to stimulate thinking about fundamentals, and how the accounting (which I believe is critical to understanding) worked. What looks like “plumbing” to Mr Parry seems to me to function through the operation of double-entry book-keeping. Richard provided invaluable illumination of the issue of interest. The matter of interest on reserves and within banking is important primarily to bankers, because they are profit and rent seekers. From the perspective of the public “money” (the stuff they trust in good – and the bad times when,oin the basis of established and repeated historical precedent, they are right not to trust banks) circulates free of interest. They can turn any stock of money they posses into an interest bearing account, bond or secirity; but save in ‘safe asset’ territory (typically the sovereign issuer of the currency), at some risk if they deal with banks or other purveyors of such insturments. The ordinary person is an outsider, competing with a network of insiders; central bank, dealer or priviliged financial institution. The public are at a considerable disadvantage, and they often pay a considerable price for the way the system operates. Historically that is proven in crises, but the power of the ‘insiders’ is increasing rapidly with digitisation and the rapid decline in the use of notes, coin, cheques; more and more power is being captured by the “insiders”.

It is interesting to me that Richard asked the authorities for clarification of the accounting of the note/coin issue (Treasury, BofE etc), and we appear still to be waiting for a clear answer. Meanwhile Peter May produced a letter from the Treasury to Ben Bradshaw MP that itself requires some further form of translation to understand.

At the same time Mr Parry’s statement: “Remember, banks have (almost) no money of their own – is is always “other people’s money” and the economics of banking depends on the SPREAD between the rate the bank borrows at and the rate that they lend at – NOT the absolute level of rates”; seems to me to demonstrate that the main purpose of nanks (as profit and rent seekers) is to turn “money” (historically notes and coin, which circulate free of interest, and is always money) as quickly as possible into credit; which immediately drops it down the hierarchy of money. for ordinary people, in periods of so-called ‘equilibrium’ this appears neither here nor there; but at other times it matters a great deal: and particularly with the digitisation of money post-Covid, this system will accelerate the process of the capture of money transactions by the banking system “insiders”, for their exploitation, until they control all transactions.

The final step will be when Big Tech finally takes over Big Banking. I invite you to think about it.

John

I am discussing this experiment with political economy colleagues, plus accounting academics

There seems much to discover here

But that will take some time

Richard

Thanks, Richard. Please keep us informed, when you can; in detail! I am ‘all ears’.

Meanwhile, as my last comment richly demonstrated, on a keyboard …. I am all thumbs.

🙂

I may bounce this off you…..

In FT today.

https://www.ft.com/content/24f51ce8-1a61-4e03-95d3-e87f2c9d938b

Now heading for the blog