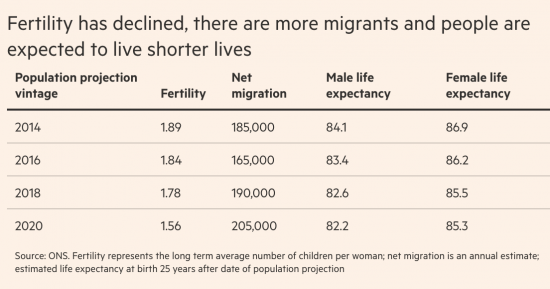

This table is in the FT this morning:

It is used by the FT to celebrate three things. The first is that the cost of education will be falling.

The second is that the biggest issue in education will soon be the battle over which school to close.

The third is that the cost of pensions will be declining as people do not live as long.

And all this is really before Covid, and long Covid in particular, has had an impact.

The FT celebrates this chart as an indication that it will be easier for the Chancellor to balance the books.

But what is there for the rest of us to celebrate in this? Not a lot, as far as I can see, unless the only route we see to reducing consumption is population reduction.

Such analysis does, however, only consider this at the purely material, or financial, level. I rather strongly suspect that the very obvious idea implicit within this data, which is that life is no longer improving, has yet to permeate into popular consciousness.

I wonder what the reaction will be when that idea does become commonplace? The perpetual myth of the postwar era was that we would all live longer and better than our parents. If there is persistent evidence to the contrary what does that make us think about the culture of consumption that underpinned that idea? Is it just possible that this idea's time might have run out and that in the face of evidence like this people might look for alternative bases for assessing their living standards when it is now apparent that the current models of economic growth cannot deliver?

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

To see life expectancy going down is simply deplorable and nothing to be proud of. Not only that, to add insult to injury if you live that long, society can’t be bothered to let you do so and look after you properly.

Maybe we should call this the ‘Can’t Be Bothered Society’?

The estate agent/housebuilding sector will rubbing it’s hands in glee at all those potentially closed down schools.

I remember (as I’m sure that many of you do) that the future was all about less work and more leisure time. Ha!

How did it come to this then?

Well, it’s simple: The wealthy (whom we have tolerated) have stolen the future. Only the beautiful wealthy deserve to live long lives, have an an education and get all their needs met. The rest of us are being nudged out of having kids, jobs, old age – everything. We’re being nudged out by the No.10 Nudge Unit, not nudged towards better ways of living.

Covid I think has changed everything for ever, as is global warming which is with us now. The problem will be our slow or negligible (negligent?) response to both.

We are moving towards a world as depicted in the sci-fi film ‘Elysium’ (2013) where the rich live off planet and leave the great unwashed to live on the earth with its environmental problems. The rich haven’t built that off-planet world for themselves yet but they just might do (Oh Hi Mr Bezos! How ya doing?’).

As for the other issue you mention – about when will people see what where this is all leading to – well lets go to Hollywood again and see this exchange of dialogue between two of the good guys in the film ‘Mississippi Burning’ (1988) – as good a treatise on the evils of fascism as you’ll ever hear on screen:

Ward:

Where does it come from, all this hatred?

Anderson:

You know, when I was a little boy, there was an old Negro farmer lived down the road from us, name of Monroe. And he was, uh, – well, I guess he was just a little luckier than my Daddy was. He bought himself a mule. That was a big deal around that town. Now, my Daddy hated that mule, ’cause his friends were always kiddin’ him about oh, they saw Monroe out plowin’ with his new mule, and Monroe was gonna rent another field now they had a mule. And one morning that mule just showed up dead. They poisoned the water. And after that there was never any mention about that mule around my Daddy. It just never came up. So one time, we were drivin’ down the road and we passed Monroe’s place and we saw it was empty. He’d just packed up and left, I guess. Gone up North, or somethin’. I looked over at my Daddy’s face – and I knew he’d done it. And he saw that I knew. He was ashamed. I guess he was ashamed. He looked at me and he said: ‘If you ain’t better than a n****r, son, who are you better than?’

Ward:

And you think that’s an excuse?

Anderson:

No, it’s not an excuse, it’s just a story about my daddy.

Ward:

Where’s that leave you?

Anderson:

With an old man who was just so full of hate that he didn’t know that bein’ poor was what was killin’ him.

So, there we are – as long as people are encouraged by fascist techniques (to exploit human weaknesses such as discrimination) to hate immigrants, the EU or to covet their neighbour’s good fortune, the wealthy will inherit the earth.

What’s true near the Misissippi, is true for the Thames, the Trent, the Severn (or a river near you).

Thanks for that Pilgrim – one of the better BTLs I have read in a while. I also remember the exchange in the film.

I find the fact that the FT article celebrates the details in the table sickening but I suppose the reason for celebration is in the name of the newspaper. Wouldn’t it be nice if we had some alternative reading – Mindfullness Times, Climate Change Times etc. to give a more balanced appraisal of the state of the world today. Also, a western version of Bhutan’s alternative to GDP for measuring the real state of a country and its citizens that is not dominated by the economy.

Anecdotally, businesses appear to be trying to hang on to valued employees by converting them from part time to full time, while self employment has been made less attractive through tax changes.

What is clear is there are major recruitment problem for many operators that relied on the pool of EU labour, before Sovereignty Enhancement Surgery.

My life expectancy has dropped by 1.9 years. And yet my pension age has risen by 2 years, from 65 to 67. Is anyone in politics now considering the surefire (and now zero-cost) vote-winner of reducing pension ages? Especially for women, who have been treated even worse than men.

Good question