As the FT is breathlessly reporting this morning:

UK inflation is likely to rise “close to or even slightly above 5 per cent” early next year, the Bank of England's new chief economist has warned, as he said the central bank would have a “live” decision on whether to raise interest rates at its November meeting.

The comments came from Huw Pill, the new chief economist of the Bank of England. It was always known that as a former Goldman Sachs banker he was a deficit hawk and enthusiast for higher interest rates. And so it looks to be.

So, the question is, do we need higher interest rates from the Bank of England to tackle what is happening with inflation now? Facts help here.

First, this is the UK inflation track record as plotted by a website called Macrotrends:

I use that data deliberately as the ONS only plots from 1987. I am aware that the longer time scale involves changes in methodology, but that is acceptable to show the required changes over time.

What is glaringly obvious is that since the early 1990s (and so long before the Bank of England was made independent) there has been an almost non-inflationary environment in the UK. No action by the Bank of England has ever really been required to address that, to be candid, barring the massive cut in rates in 2009, which was in any case fiscally motivated.

The blips after 2010 were signs of the economy reopening: they rapidly fell out of the system, just as that after Brexit has. Over the last decade, without significant interest rate changes, inflation has always returned to the mean, which is very low.

That is unsurprising. That is how an index based on a twelve-month average works, most especially when inflationary pressures are short term - as is obviously the case in the UK. Unlike the 1970s, we have no environment where long term inflationary pressure can be created, barring that from external sources entirely beyond the control of the UK government and the Bank of England and those are not in play right now on any significant scale.

So, what rate change are we talking about?

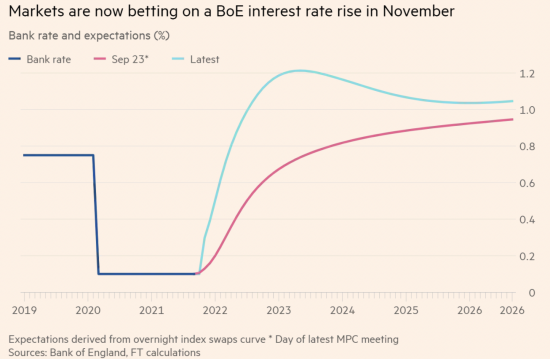

The FT plots expectations like this:

The belief is that rates might reach 1.2% in 2023 and then fall.

Coincidentally, Feb 2023 is when it is most likely that inflation will begin to return to 2% or less as the current inflationary trends fall out of the 12 month rolling index by then.

In other words, rates might increase to a bit above the level they were in February 2020.

So, four thoughts based on this evidence.

The first is that this inflation is all supply-side driven as a result of shortages post-Covid. None of it is demand-side driven. None seems to relate to QE or any aspect of monetary policy. None of the causes can in any way be impacted or corrected by an interest rate change. We just need to sort out lorry drivers, and gas supplies need to normalise. In that case a Bank of England reaction cannot solve any problem that we face.

Second, the inflation will go away, almost certainly, even if (and maybe because) the Bank of England does nothing. That's what has happened for three decades during which I suggest the Bank has had remarkably little impact on inflation.

Third, any change in rate now will have little immediate impact on spending capacity: most mortgages are fixed for long periods. So any change is a token gesture in the short term.

Barring that is a fourth thing, and that is that the Bank wants to signal to the Chancellor that he must cut government spending to allow for an interest rate rise. Inflation does already increase the government cost of borrowing because there are significant sums in issue in inflation-linked bonds. And for each 0.1% interest rate rise right now the cost of paying interest on the central bank reserve accounts held by commercial banks with the Bank of England will rise by about £850 million a year - which the Chancellor will use as his excuse to impose austerity.

So, all rational evidence suggests that no action is now needed by the Bank on interest rates. But the politics of the Monetary Policy Committee, wanting to support an austerity agenda from the government, suggests that a change can be hinted at right now - even if they then decide not to deliver it, because by then the harm to the wellbeing of the country by austerity being re-introduced will have been done.

This is what this talk is about. And all of it is opposed to the best interests of the ordinary people of this country.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

Very interesting.

So a rather false situation is being manufactured to excuse policy. Or – from a progressive point of view – lack of policy. This is to thwart the public sector unions perhaps who want a larger pay rise?

But from what I know, even to charge a Government interest on using its own currency levied by a bank that it owns is just a political confection anyway.

Another interesting point is this betting going on in the markets – I assume that we can take literally as ‘betting’?

I wonder how this plots against wage rises. I expect they have not risen very much more.

If however, we plot the rise in property prices, that will have risen at a much higher rate. Would I be right in assuming that rent and mortgages are a relatively greater burden than in the early 90s? And if so, is not that anti inflationary as people have less to spend on goods and services?

Picking up on the false theme that inflation is a tax on the poor, so it justifies higher interest rates as a control, it got me thinking about the latter a bit more.

With real taxation, I have learnt that it is the price of having a stable useable currency for a society and a way for the Government to influence fiscal policy; as means of giving a currency its value and settling bills owed to Government etc., and the way it fits in with democratic accountability. Richard’s book ‘The Joy of Tax’ sums these positive attributes up superbly.

However, I feel that can’t you also see interest rates as a form of taxation too? They certainly destroy the money of the debtor.

When you look at tax it seems to me to be a charge for using the money system created by Government. Except of course, money is also issued by private banks as a form of debt attracting interest to the public.

This privately issued debt we know is huge in itself and problematical. But it needs looking at in this context.

The Tories use of interests rates (monetarism etc.,) has been a back door policy of putting up taxes for me on the end users of debt under the guise of controlling inflation.

In the Tory neo-lib world – honest, forthright taxation by Government is seen as theft and illegitimate.

But apparently it’s OK for banks – and those working on behalf of rich investors – to charge a ‘tax’ on the debt money they provide in the private banking system.

In the end therefore, those advocating that inflation is a tax on the poor are just actually advocating another equivalent tax style effect increase on another part of the money income/outgoing system that will still cause hardship for those on lower incomes who are more likely to incur debt just for living expenses, and even on those servicing debt elsewhere from houses to car loans.

Another way of looking at it, is that some want a private money provision system with its own tax system (called interest) giving them therefore the exclusive benefits of that tax. But the Government is not allowed to do the same for the money it provides. Interest rates are nothing but a private taxation racket of the banks and investors (like those who started up Wonga many moons ago). And a Government like this one – captured by big money – is more than willing to help its funding constituency.

Interest rates are simply the privatisation of taxation to me without the money destruction capabilities of real Government tax (which acts as a real curb on inflation) on large concentrations of money in the system . Therefore all we have is a merry-go round of built in inflation of regular hikes in private money debt yields to those who lend it. It also explains why Thatcher’s flirtation with pure monetarism didn’t work but also that time has reified that it was never designed to do so.

There is actually NO intent whatsoever in my view in such a system to curb inflation. Because inflation as controlled as proposed now and executed in the past benefits the issuers and funders of debt. That is where I think we are.

Certain thoughts come to mind when one considers all this.

1) It’s a massive sleight of hand by those advocating interest rate rises now. Massive and mendacious.

2) How much is enough? It’s a relevant question to the monied and powerful that even though they already have everything that they still expect to be enabled to get more.

Bear in mind I think about these things with a big green ‘L’ on my back – I could be wrong but I thought I’d share it anyway.

Read well to me

Thanks

Well thank you.

One of the things I may have picked up on in all of this is the abuse of language.

If ‘inflation’ is a rise in the price of something or things that causes concern, how can deliberately ‘inflating’ the cost of borrowing (interest rates) work? But the inflation word is of course not applied to interest rate rises in how it is presented to the public because what they are doing is apparently fighting inflation with inflation.

When you consider the impact on the debtor and compare that to the impact on debt issuer or wealth holder? And of course, the higher interest rates attract under tax wealth into the credit system to cause bubbles.

Ultimately the claim of interest rate rises in economic inflation scenarios is extremely dubious in my view.

I think Johnson and Sunak have to be very careful – I remember the late 80’s and early 90’s when interest rates soared and repossessions along with them. Mind you – the Tories were punished in 1997 for this.

But a lot of pain and misery by ordinary people was incurred beforehand. Today austerity, the Covid, then BREXIT and now interest rate hikes.

In one perverted sense, you’d like to see it happen just to see if the public would tolerate it.