A significant paper was presented to the annual meeting of central bankers at Jackson Hole last week. It had this seemingly innocuous title:

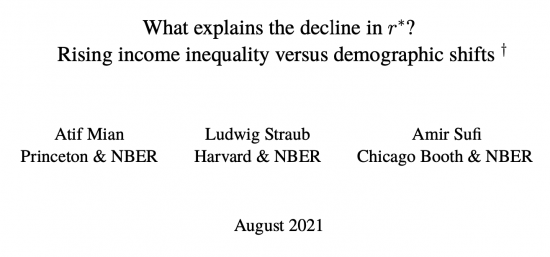

In this context r* is the natural rate of interest. As the paper (which uses US data) notes, the trend has been heavily downward:

The long-term trend is markedly in this direction.

The paper accepts that there are more savings in the world. This is widely acknowledged. It also accepts that more savings with no one seeking to use them means lower rates of interest and that this would have happened irrespective of government policy to tackle economic crises.

What the paper then discusses is whether this is the result of a demographic time bomb - the baby boomers working their way through the system - or because the growing inequality in the distribution of wealth is the cause of there being excess savings that are suppressing interest rates.

In the UK Charles Goodhart and others have suggested that the glut of savings is because of baby boomers saving for pensions. As a result he suggests that as those of that generation retire - as they are doing in increasing numbers - there will be a reversal in rates. That's part of a bigger thesis on resulting changes, but fairly summarises their position, I think.

The authors of this paper do not accept that argument, which I have always found implausible. They instead argue that the increase in rates is because the wealthy elite is getting wealthier right across the age range and that this is the reason why rates are declining, because they of course have an incredibly low marginal propensity to spend. As such, once their savings wealth begins to rise and rates fall, creating the perverse corollary that this increases their wealth still further as a consequence of the way in which market valuations work, a cycle of ever-increasing inequality is created with ever greater downward pressure on rates resulting.

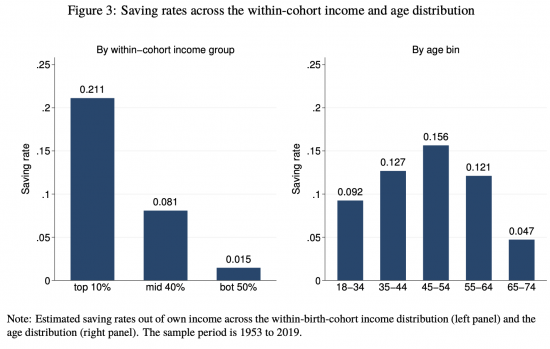

What they suggest is that the savings rate by income group is a much stronger indication of savings growth than is that by age group:

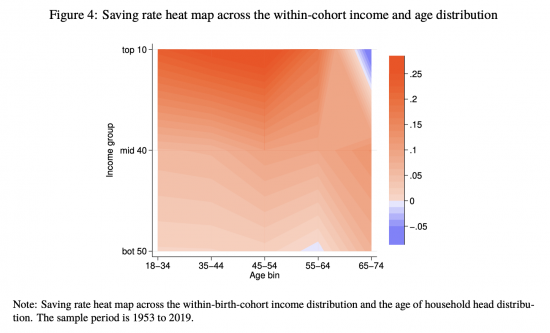

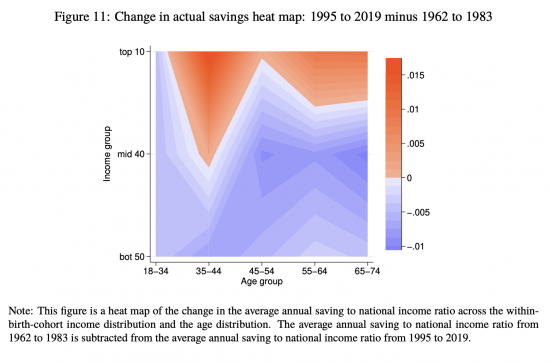

And they reinforce this with some fascinating heat map analysis:

Savings are high across all age ranges amongst the wealthy (excepting old age, where there is inevitable dissaving) and not but a single cohort. Savings are driven by income-related ability to save, and not age.

This is reinforced in this heat map:

As the authors note:

For every age bin except for the 18 to 34 group, the top 10% is saving significantly more in recent years relative to the pre-period. The bottom 90% is saving less in almost every age bin. As with saving rates, the crucial variation is across the within-cohort income distribution, not the age distribution.

In other words, the wealthy are saving more, and this trend is self-perpetuating.

As Robert Armstrong said of this in the FT of this finding:

The political implications are particularly nasty. Inequality, in their view, is self-perpetuating, with the feedback loop running through low rates. Excess savings of the rich depress rates; low rates push asset prices up; the rich get richer still.

What is more, government action is reinforcing this, and the locked-in rates can't be changed without risking economic chaos now. But as Armstrong adds:

For how long are the people who sit outside this wealth machine — a majority of voters — going to tolerate this?

That's the trillion-dollar question. And tackling this inequality is one of the biggest issues that we face as a society as a result, without the need as yet really being acknowledged outside those hotbeds of international socialism at the International Monetary Fund, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development and World Bank, all of which are calling for wealth taxes.

My suggestions on how to tackle wealth inequality through tax can be found here.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

Fascinating paper.

Lazily, perhaps, I had thought declining “natural rates” were mainly a demographic and technological phenomenon . Whilst rising inequality has always disturbed me I had not really seen this as a driver of interest rates. This paper has made me think again.

That’s why I thought it important

Robin Harding also mentions this paper in the FT today – but starts with a look at Japan. He observes that, despite a declining pool of young workers and a high level of vacancies, wages are not rising. The assumption was that, over the last 20 years, (yes, really 20 YEARS!!) massive QE and a declining number or workers would deliver inflation…. but it has not.

I don’t know what is going on here but if Japan is a “leading indicator” it does tell me two things.

First, inflationary fears are unfounded (for all the reasons you have identified elsewhere). Second, that labour markets are different and don’t behave as expected… which is why they need to be a direct object of economic policy rather than a “residual outcome” in pursuit of other goals.

Spot on

What is happening here? That’s a great question, My answer is that the power to oppress wages remains considerably greater than any market pressure to increase them

That is, incidentally, why I think that Larry Elliott’s view that rising wage rates will justify Brexit in the end is wrong: I don;t see that happening for that reason

We need something more radical to achieve that

At my local garage, the son of my previous favourite mechanic has taken over since he retired.

As a result he has put up prices. He’s young, just married and wants a family.

This has been noted by the customers who have duly started to go elsewhere – some of them quite well-heeled too.

It’s all very well saying that wages will go up, but it’s not as simple as that is it? The other question is are people prepared to pay the cost – you have the well-heeled who notoriously undervalue the work, along with the increasing majority who can’t afford it.

Night-follow-day pronouncements like Larry’s are just not helpful.

You might see a blip, but I just don’t see wage rises as sustainable because as Paul Krugman says, ‘everyone’s wages is someone else’s wages’. And this is an economy denuded of cash.

Along with ‘a country is not company’ one of the best things Krugman has ever said.

Wow! Economists discover that if your increase supply (in this instance savings) and the demand is relatively inelastic, the price will fall – and as supply continues to increase the price will fall even further. Who’d have thunk it? And central bankers were congratulating themselves that their QE was successfully flattening long-term interest rates. They were just going with the flow and exacerbating the problem.

Isn’t it wonderful how they can discover these things when it’s no long likely to be politic, profitable or popular to lie or ignore these blindingly obvious things as they did previously.

Another reason for the lack of wage rises is the drop in trade union membership and militancy. Maybe with a new leader at Unite things may warm up a bit.

[…] Cross-posted from Tax Research UK […]

is this because asset prices increase to reflect lower interest rates?

Yes

First of all, there are always multiple factors but the most obvious ones are the aging population, technological progress, globalization, loss of wage negotiation power and inequality. Combine all of them and you get very low rates. Throw out half of them and you merely delay low interest rates for a few decades.

I personally do not see the harm in low interest rates. In my opinion interest rates are set by the availability of solvent borrowers. Savers go to banks to maintain the purchasing power of their money. If held in the form of cash it would lose its value from inflation. Therefore it is not savers that provide a service to borrowers, it is the borrowers that provide a service to the saver. The borrower is not a borrower at all, he is actually a safekeeper who is trying to store value in the real world. The fact that building a factory is such a good store of value that it actually earns a return is just a happy accident and the borrower is willing to let the saver have a share in his success. However, the saver didn’t do nothing, by holding onto money and not spending it, he created a gap in the economy and that gap was filled by the construction of the company. If that hole did not exist then any additional borrowing would simply result in inflation. The interest rate merely tries to balance supply and demand between savers and lenders.

Now, what if we hit the end of the easy growth opportunities because there are less young consumers, industries become less capital intensive, other nations start growing their economy, people don’t have money to spend and those that have money to spend simply do not do so?

Interest rates go down, because there aren’t any solvent borrowers left. The amount of surplus value they can promise you goes down. Instead, a new class of safekeepers appears. They do not store value in companies, they store value in real estate. The returns on housing are low but they are consistent and guaranteed by the monopoly of land. So what we are seeing here is an attempt of those with money to maintain their wealth through questionable practices.

If you were to introduce a holding fee onto land, a land value tax, then the problem might disappear.

When interest rates fall negative we then discover a third class of safekeepers. Rather than store value in something that maintains its value like real estate, they store value in something that fails to maintain its value today, namely excess capital and excess labor that is currently not being used at its full production capacity but might be used in the future. A factory requires maintenance and an unemployed worker needs food even if neither produces any output. Rather than work for the present they work for the future.

I hope it is clear enough that positive interest rates are motivated by scarcity and the investment is earning a return by reducing scarcity. When there is no scarcity left, there is no return left. Interest rates become 0%. Humanity is winning so to speak. When you go beyond scarcity, meaning there is abundance, interest rates become negative. Abundance is not self supporting. A plentiful harvest will rot if it is not consumed yet humans will starve if they harvest too little so they should work even if they do not intend to consume all the food. If capitalism wants to beat Marx at his own game, then it would have to accept the possibility of negative profit.

You t5e linking saving and investment

In banking that link does not exist