There are moments when it is wise to think a reconsideration is appropriate. My suggestion for perpetual debt did not go down well yesterday. But it did create invaluable debate. Even 100-year debt was not seen as a zinger. But long term debt at near enough zero per cent as a way of locking in rates on money seemed to be acceptable.

Let's be clear what money I am talking about. It is the central reserve account balances held by the UK's banks and building societies with the Bank of England. These balances are described by the Bank of England as follows:

We are the UK's central bank. Our balance sheet is special for one key reason — the nature of our liabilities. Central bank money, whether in the form of banknotes or central bank ‘reserves' (deposits held with us by financial institutions), provides the ultimate means of settlement for all sterling payments in the economy.

This gives our balance sheet a central role in supporting monetary and financial stability.

These balances are, then, money par excellence. And those who claim that they are broad money are wrong - the Bank of England says so. In this context, note this from a speech from Monetary Policy Committee member Gertjan Vlieghe in April this year:

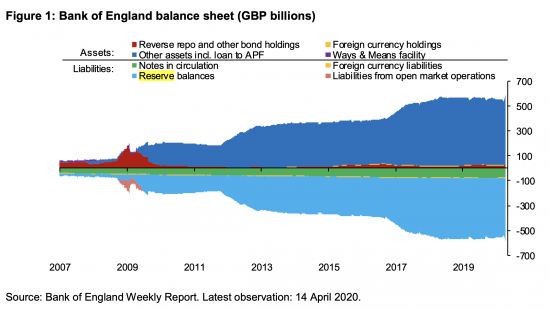

Narrow money goes up with every QE issue. That is because QE creates central bank reserve accounts. And they are narrow money. This is reflected in this representation of what is claimed to be the Bank of England balance sheet from the same speech:

I say 'claimed to be' for a reason: no such balance sheet is ever actually published because this consolidates the Asset Purchase Facility (APF) notionally is run by the Bank of England and which actually legally owns the repurchased gilts into the Bank of England accounts but for actual accounting purposes that cannot be done as the APF is under the control of HM Treasury: although technically a subsidiary of the Bank of England its accounts are not consolidated for this reason. The above is then a Bank of England / Treasury balance sheet, but the point remains the same. As QE rises, so too (near enough, but not precisely) do central bank reserve accounts with the UK's banks and building societies increase.

For those confused by this, and who wonder what they do with this 'money', please remember what money is: it is simply a debt. There is no physical moving of assets here. And remember that no money is reused in banking. Bank money is simply a record of a debt. The APF has bought gilts from banks using money created out of thin air for that purpose by the Bank of England and that debt remains outstanding to the banks. There has been nothing to redeem it. At present there is about £800bn still, in effect owing, to be cancelled either by tax or new debt sales by HM Treasury, which is all that these balances of central bank money can effectively be used for.

In the meantime, those balances sit as deposits on commercial bank balance sheets. This is from the same speech byGertjan Vlieghe:

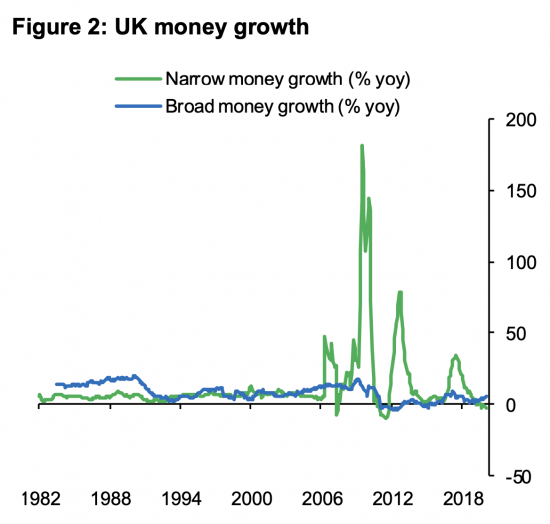

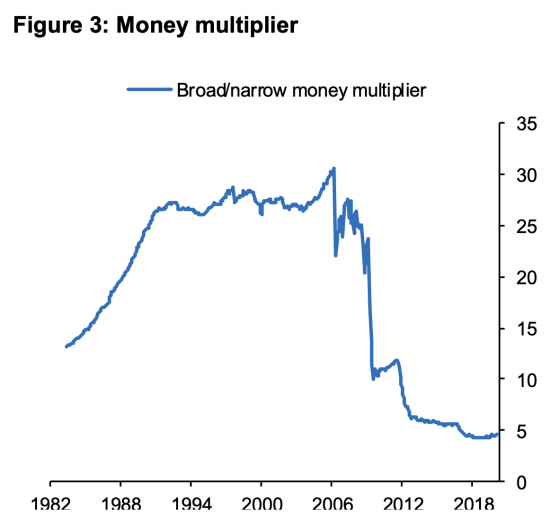

In 2006 for every pound of central bank money (broadly cash back then, because central bank reserve accounts were out of fashion then and banks extended each other credit, which they no longer do) there were roughly £30 of commercial loans. This is where the claim that private banks make the vast majority of money came from.

By April 2020 that ratio was £5 of bank loan for every pound of central bank money. That ratio will now have fallen again: there has been £200 billion more of QE since then.

So, let's be clear about three things.

First, private banks do not lend their central bank reserve balances on. They create new money when they lend.

Second, there would appear to be more central bank reserve balances than are needed for normal purposes at present (but the March 2020 market freeze was a warning shot on the need to have sums available to ensure liquidity between commercial banks; that was why £200 billion of QE was created then).

Third, if there are, on a day to day basis excess central bank reserves, and that seems to be the case given this loan to narrow money ratio, then the question that I ask about what can be done to manage this issue when the Bank of England thinks it necessary to control rates by paying interest on these balances does seem a fair one.

So, let me retreat from perpetuals. I know when I am beaten (even if part of narrow money is, of course, zero rate perpetuals - because that is what notes are).

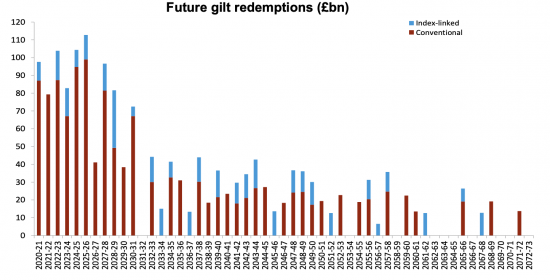

And let's talk no more than 100 years. Just to put this in context the Debt Management Office suggests current debt profile is as follows:

There is already long-dated debt, as will be noted

But what we have in the case of the relationship between the Bank of England and banks with regard to central bank reserves is something different. The banks have an asset that they did not choose to acquire, but had little choice but have imposed upon them in their role as intermediaries. And as is apparent, this asset is not, as such used in their business except for the purposes of inter-bank settlement, as the Bank of England has noted.

So the question to ask is can the risk to the Bank of England on interest cost be hedged? That is what my video yesterday was effectively asking. My suggestion remains that it can be. First, that is by recognising that these balances are narrow and not broad money. Second, it is by recognising that whilst narrow money is important its use is limited. And third, it can be by accepting that the amount of that narrow money that need be in issue with a variable interest rate need not be the full value of the balances now held. I am not sure that any of these suggestions should be that contentious.

So what to do? Let's stick with the need for some of these central reserves to continue as now. And let's then suggest that a form of long term debt that is tradeable between the holders of these balances and the Bank of England alone is an alternative for the remaining balances. In other words, it remains a means of settlement. It remains narrow money, in effect. That is only possible with a very long redemption date. And let's suggest that a fixed rate is appropriate on this money. The average cost of government debt right now is 0.3%, which if it was used for these excess balances would add an immaterial £1.6 billion at most to the cost of serving the national debt, and provide banks with a rational reason to opt into such issues now.

Is that viable? I stress, I am exploring ideas. And I think this restructuring of what looks to be an unsustainable balance sheet as to form, but nonetheless necessary balance sheet as to function is necessary and that is why I am exploring this.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

Blimey ,you have gone from giving banks the 0.1% they currently get for holding reserves (that they don’t need) to now paying them 0.3%,is that right?

The banking sector already gets well subsidised ,I don’t think you could justify this to ordinary people who would see this as yet another cave in to the banks.

Why are you so worried about the BoE’s balance sheet? They haven’t seemed to worry about carrying past QE for 11 years so far, it is just numbers on a spread sheet after all?

You can tell I’m not an accountant : )

I’m trying to buy them into a long term interest rate that can be locked at £1.6 billion pa for 40% of what is called the national debt

Overall I call that a deal

And yes I am committed to MMT

I also live in the real world

“My suggestion for perpetual debt did not go down well yesterday. ”

Really? Maybe stop using neo-liberal framing.

The “National debt” is simultaneously the “National Savings Account”.

Maybe frame it this way? “Yes, folks! I propose that we try to increase the size of the National Savings Account!”.

It will be better received 🙂

I am well aware of the MMT framing

]I am also well aware that there is a world out there not yet framed by MMT

We cannot wish it away – it is real and there are still obligations and consequences arising from it – and I live in the real world where those can’t be dreamed away

£800 billion of asset / liability exists

And it is not a national savings account – it is held by ban ks and building societies and they are not the same as national savings

What I wish to do is anchor these issues so we can move on

Is that wrong?

Well done for exposing how the establishment pretends through legality boundaries that the BoE is not part of the UK government which then allows a lot of accounting jiggery-pokery to take place to pull the wool over the eyes of the sheep!

It puts your arguments in context

If one consider the BoE, the APF, the DMO and the Treasury to all part of one big (un?)happy family — which I think you do (and which is right) — it seems to me that the whole process is circular.

QE itself is circular in the sense that the government is merely buying bonds from itself with created money…. but to then require that created money to be spent buying bonds puts us back to the old days where government spending was matched by sale of bonds.

Well, almost…….there is a subtle difference. The bonds you propose are not are not eligible for anyone but clearing banks to buy. Does this make the scheme worthwhile?

A look at Barclays Bank PLC (just the UK retail and business bank, not Barcap) we see reserves at end 2018 were £40bn and 2019 £25bn (versus equity of 16bn). It raises two questions.

First, if we had forced Barclays to put half their reserves into these bonds at the end of 2018 (20bn) then they would only have 5bn in cash reserves now — would that be sufficient for their clearing business? It is essential that these bonds are easily converted into “proper” reserves and with only 12 possible buyers (other clearing banks) that would be an issue. Gilts would be better.

Second, if the interest rate risk were unhedged the potential losses on these bonds are huge. If we assume a perpetual at 0.5% they would lose half their money if rates rose to 1% and would be forced to cut lending to meet capital requirements. (Same argument applies for 50 year bonds but it would be less extreme).

In short, I still don’t like your idea.

As I see it your scheme is trying to do two things. First prevent “windfall” profits for banks (0.10% for nothing); second lock in low rates for the government to prevent interest costs soaring as rates rise.

I think there are better solutions.

(A) Taking away the free lunch.

When government decides to spend money the payment from the Treasury to an individual is mirrored exactly by a movement of reserves from the Government’s account at the BoE to the reserve account of the bank that said pensioner holds their account. When the individual pays tax or buys gilts reserves move back the other way. A bank’s reserve position with the BoE is a direct reflection of customers depositing or withdrawing money. The profit is a function of the spread between what they pay depositors and what the BoE pays them. This is currently 0.10% and not a lot given that most of us enjoy free banking. Indeed, banks hate low rates as this spread is so compressed — it is typically much wider and if rates rise they can earn more. We could cut the rate paid on reserves to zero but given the interest rate outlook it could see the end to free banking. Be careful what you wish for although a look at interbank lending suggests that it should be cut to 0.05%. Also, perhaps the regulators could intervene to keep this spread narrow if/when rates rise?

(B) Protecting government against higher rates.

Two ways to go here. First, to realise that we are in an MMT world. Interest payments are putting cash in peoples pockets as surely as paying pensions or doctors’ wages. If we feel bondholders are undeserving of this money then we can use the tax system to compensate. Either impose withholding tax on gilts or (better) re-jig the whole tax system away from taxing labour to taxing unearned income/wealth.

Second, we know that QE has not led to a rush to invest in real economic activity. It has driven gilt yields down and property prices up with little benefit to jobs and serious detriment to pension schemes and potential home buyers. Better would be to target long term gilt yields rather than place an arbitrary size on a gilt purchase programme. I would suggest that with an inflation target of 2%, long gilt yields should be in a 1.5% to 2.5% range (short rates still at zero). Given rates are at about 0.75% that would mean quite a lot of issuance to bring the rate up and this would lock in borrowing costs and reduce the excessive level of reserves without dampening lending to the real economy.

QE is fine but it takes two to tango. In some sense I think the latest QE is the BoE giving the green light to government to really spend…. but the government has not responded as it should have (Green Deal, more generous sick pay etc.)

Hmmmm….

I am not yet convinced

But I am enjoying the exchanges

“But I am enjoying the exchanges”.

Good – it is what a blog is for!! Thanks for running it so assiduously.

🙂

If I understand Mr Parry’s point about long-dated gilts, and the damage to pension funds, am I correct in thinking this may provide and answer to my question on another thread about the reluctance of pension funds to participate in reverse auctions by giving up long-dated gilts?

Secondly, the more bank accounts are used instead of cash, and given the importance of free banking for so many users throughout the economy, combined with the transparency of the relationship between the commercial bank end-user’s movements in deposits and the reserves so directly reflected at the central bank; do we really need the commercial banks we have (financial investment conglomerates), or would we not be better returning to a clearly delineated, old-fashioned dual banking framework; very basic commercial banks targeting (say) free universal banking, and the ‘buccaneers’, the investment or ‘merchant’ banks out there where we can see them: no more ‘chinese walls’?

Yes

But what I suggest we need more than anything is Girobank again

Basic bank account, deposit account, payment card, credit card

No more

Forgive a frustrated QE self- studier

The BoE balance sheet describes

! central reserve balances

2 deposited from the financial institutions

3 ^& are liabilities in BoE’s balance sheet

RIGHT SO FAR

4 then the QE is deposited by said financial institutions back to BoE===seems a bit circular as Clive has said

My questiion. Richard , is what happens to the corresponding asset in BoE.s balance sheet to offset the liabilites ? Surely it must have equal ” value ” which the Govt. puts to good ? use ?

Really confusing ,sorry !

The process is

1) the BoE creates money be lending to the APF

2) the APF spends that via the BoE to buy assets

3) the BoE then owes the clearing banks – which debt is what the central reserve account balances record (remember money is debt)

4) the APF still owed the BoE for the created money – an asset for the BoE

5) the APF owns the assets

6) The Treasury controls the APF

7) The Treasury has the gilt liability – the two net off, but nit precisely because of changes in value that no wants to account for and so pretend they do nit need to address

8) subject to price variations on repurchase the net is 1) BoE is really owed money by the Treasury (Dr) which has 2) been injected into the economy via central bank reserves (Cr). The APF nets out.

Glaringly obvious, isn’t it?

Mr Gray’s choice of phrasing his question has produced a beautifully clear 8-point explanation in response. May I suggest it would make

a) an excellent blog all on its own, and much wider read than a comment deep in a thread.

b) an excellent Twitter explanation that I had would circulate widely.

Description is what MMT does best.

Noted

I have copied and pasted to do the blog

If it’s miserable tomorrow…

Completely agree about Girobank – it would also help sustain the local Post Office network.

All the debate here is well above my pay grade unfortunately, so please bear with me if I ask two naive questions . First- since the Bank of England now holds this government debt , is it not cancelled out? Second, I have read on numerous occasions that MMT says that the government can choose whatever interest rate it wants and keep it there as long as it wishes. If so, what’s the problem?

1) I say yes. They say no. But you can’t owe yourself money and none has ever been sold back to the market

2) MMT is right. The problem is the legacy of what has happened and how to manage that

Because the £875 billion QE debt is – in fact – a verbal construct to get around an EU banking rules, why not adopt the strategy employed by the banking sector, when faced with too many bad debts: a “bad” bank?

1. Create a “bad” bank.

2. Transfer the QE debt into the bad bank.

3. Liquidate the bad bank.

There are no creditors to worry about.

Because the double-entry resolved this much more simply

Patrick’s idea is a very cunning plan.

And unnecessary

And yes, I get the joke…

Thank you Jeff. I prefer to resolve problems once and for all, but that is not to everyone’s taste.

Richard. thanks for your time & explanations.

still working my way through it

The consolidations/balancing off I can follow OK

stuck with the accounting entries for the BoE creating money

but Hey Ho

the lockdown does have its uses

I’ll get there !

I will try to do more on this …as I said