The IFS is peddling its usual nonsense on macroeconomics this morning. In a new report

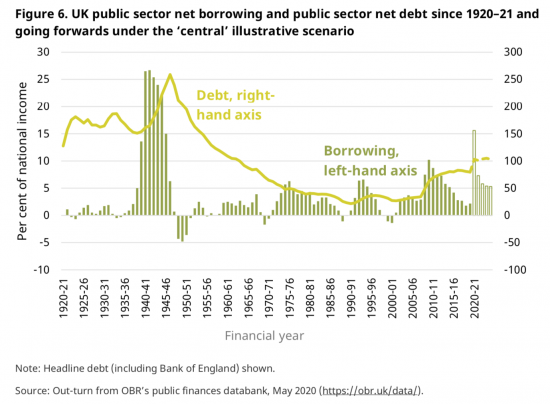

They make some predictions for the economy, most of which are already wrong since in their preferred scenario (in which they, somewhat improbably, ignore the possibility of a second wave of coronavirus) They assume, using the conventional measure of government debt which ignores quantitative easing, that debt will not exceed 100% of GDP until sometime next year.

Using this scenario they plot the likely progress of debt as follows:

It would seem that they are trying to be reassuring. But what I am more interested in our their comments on interest costs. On this they say:

Furthermore, as long as the government can continue to borrow cheaply, it seems appropriate to be comfortable with elevated levels of public sector net debt. Indeed, under all of our scenarios, debt interest spending would be lower over the next five years than was forecast in March. A key risk with such an approach is that the cost of government borrowing may rise. This risk is particularly important to highlight given the Bank of England's programme of quantitative easing, which has the effect of increasing the exposure of the public finances to changes in interest rates with borrowing being effectively financed at Bank Rate rather than being locked in at longer-term gilt rates.

This is where the IFS show their usual lack of reason coupled with their standard incomprehension of macroeconomics.

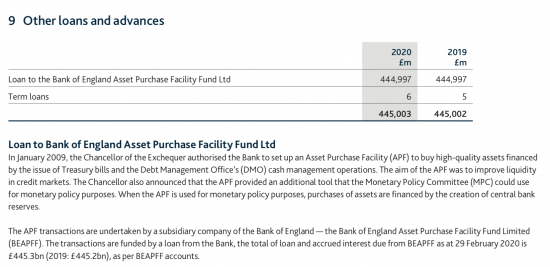

Let me explain the facts. The concern is that quantitative easing cancels government debt by buying government bonds from the private sector, to whom they have been sold, with the net consequence that the amount of cash in private sector banks increases. These are then held on what are called central bank reserves. These do not move precisely in line with the amount of QE that has been done, but they are clearly related. Since the Bank of England happened to issue its accounts to 29 February 2020 yesterday we have some up to date information on this. This is the amount lent by the Bank to buy QE debt at that time:

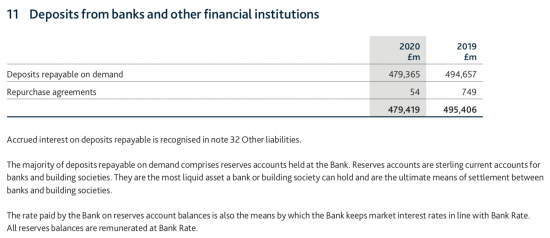

And these are the central reserve balances:

I should add that the actual value of gilts owned by the Bank is somewhat more than £445 billion, but that is a story I will come to: I mention it now to make clear that the assets more than cover the liabilities.

Now let's return to the interest point and the IFS claim (which I repeat from above) that:

This risk is particularly important to highlight given the Bank of England's programme of quantitative easing, which has the effect of increasing the exposure of the public finances to changes in interest rates with borrowing being effectively financed at Bank Rate rather than being locked in at longer-term gilt rates.

There are several points to make. First, note what the Bank of England has to say in that note 11. It is:

The rate paid by the Bank on reserves account balances is also the means by which the Bank keeps market interest rates in line with Bank Rate. All reserves balances are remunerated at Bank Rate.

In other words, the Bank of England now has (which it did not have before 2009) a mechanism to enforce its bank rate in the market. What it will pay on the central bank reserves of banks and building societies sets the short term rate of interest in the economy. That create is not set by markets. It's set by the Bank of England.

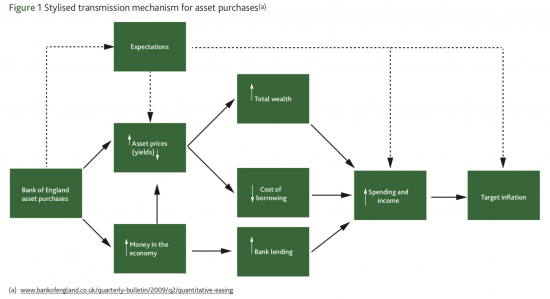

And long term rates are also set by the Bank now. That's done via QE. I use this diagram on how QE is meant to work from the latest accounts of the Bank of England Asset Purchase Facility Fund Limited, also issued yesterday (same link as above) to illustrate this point:

The aim of QE is to keep interest rates low.

So, both short and long term interest rates are under the control of the Bank of England now.

In that case, why would they rise, as the IFS think likely? Interest rates rise because of:

- Market pressure, which the BoE can counteract, as noted above;

- The economy is overheating and rates need to rise to reduce demand, which is unlikely for many years to come;

- There is an external shock such as Brexit or oil price increases and rates rise in a vain attempt to support the value of the currency;

- There is a general rise around the world.

The first two I have already dismissed.

The third is unlikely: rates have been allowed to float down because of Brexit and the trend will continue.

The last is almost inconceivable: the pandemic and crisis is worldwide and no one is going to be increasing rates anywhere in the world to address it. In addition, the long term trend in rates around the world (we're talking a 500-year trend here) is downward: there is no sign at all that it is going to change. Indeed, negative interest rates are happening. And that is because the world is awash with savings: there is a glut because of the gross inequalities that exist in the world and no one wants to pay for them.

In other words, the chance of any serious rate rise is as close to nothing as it is possible to get. So what is the Institute for Fiscal Studies raising the concern for unless a) it can't follow this logic b) it does not know about it c) it's trying to create a risk that does not exist to support austerity? I think (c) the most likely, but who knows? However looked at, they're wrong: this is not a concern.

It's time that people realised that interest costs are not a concern whatever the level of debt right now and it's time that think tanks stopped saying that they are.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

IFS

Infinitely

F**king

Stupid

I’m absolutely sick to death of this lot. Panic merchants the lot of them.

The interest rate on a gilt is fixed for the life of the gilt. If you sell a 30 year gilt now at 1% pa then it will remain 1% until 2050 whatever happens to market interest rates over those 30 years. It is also the case that the interest rate on the soon to be £735 billion of gilts owned by the BoE is zero since the bank hands the interest back to the treasury. So the only thing that can possibly be susceptible to changes in market interest rates would be new gilts issued in future years. So there might be a risk at the margin for the gross additions to gilt issues in the future but there can not be any risk to the stock currently is issue. To suggest otherwise would simply be ignorance. What there is would be a risk that the market price of gilts would fall if interest rates rise. Currently a lot of older gilts pay nominal rates of 4-8% meaning they can be valued at say £150 per £100 face value. If rates rose to that sort of range the gilts would fall back to the £100 face value so the present holder (probably a pension scheme) would take a capital loss. The BoE could also show a capital loss on its gilts, but that is notional and the BoE and Treasury could at some point just agree to write off the whole lot. Maybe a neater way – the Treasury could have the Royal Mint issue a £735 billion face value coin and give it to the BoE in settlement. Coins remain the only ‘real’ money in that they are not an IOU of the state.

It’s annoying when people peddle untruths through ignorance but when it is done deliberately to push a particular agenda it is infuriating.

If we ever require higher rates it will be a high quality problem to deal with!

Of the 4 reasons that rates might rise I DO fear No. 3. I am worried that incompetence of the current government will lead to GBP devaulation (BREXIT, poor COVID management etc.)…. rather more worried about the incompetent response we might get to such a devaluation (higher rates and austerity).

Finally, if one looks holistically at the system, interest payments from the Government to the private sector are just one of many flows. The beauty of MMT is that government can respond through fiscal policy. For example, raise tax rates on savings, make income tax more progressive etc.. So even in the unlikely event that rates rise it is STILL not a problem.

I tried, but did not succeed in magnifying your QE diagram. I am disappointed that I cannot read it.

It is in here https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/asset-purchase-facility/2019/2018-19

hold down CTRL key and keep tapping the + key and it will magnify in browser on desktop usually ( use CTRL – to zoom out and CTRL 0 to reset )

It works!!

And I’m grateful!

Muchas Gracias, el Deco! Café Solo para el Deco, Barista por favor!

The IFS can’t do systems thinking like most of the country’s politicians! The UK did nearly 300 years of silly Gold Standard thinking and still can’t understand why it shouldn’t carry on with the principles that underlay it! The country is backward!

http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=45106

Why do those who use the household analogy of debt regard a government debt which is virtually 100 per cent of yearly total income [in reality it is just 67 per cent as they owe themselves the difference] as woeful and must be avoided, whereas a bank could lend me 600 per cent of my gross income [750 per cent of my net income] for a mortgage, and that is deemed acceptable?

Always worth remembering that bank is charging you interest on money it never had in the first place, banks being currency creators not warehouses. When is the unfairness of that going to be recognised, let alone addressed?

To stop them from saying this one would need to look at why they are saying this and why they are being given so many prominent platforms from which to say it.

They’re saying it because they’re being paid to say such things. By secretive donors who believe it is in their interests to do so.

As these donors are secret one can only speculate at the motives. It could be ideological or there could be a disaster capitalism motive or some other motive entirely.

Perhaps we can deduce the motives from the effects of their campaigning. Generally they want small state and lots of privatisation. Perhaps they oppose financing state spending by government borrowing because they want the government to have to sell off the family silver, so to speak.

I think it’s an error to expect to convince them by refuting their arguments. It assumes they’re being sincere and making those arguments in good faith. They’re tactical operatives deployed to influence public opinion in favour of shadowy interests.

What we should do is contest their legitimacy. Why are these people in the TV studios at all? Why are so many politicians part of a revolving door system where they work or write for such organisations then go into government then receive well paid sinecures on leaving office?

The Johnson/Cummings government is a low point in public probity. For various reasons voters aren’t worried that the people they vote into office are corrupt as long as they represent some higher priority (eg Brexit, or patriotism or whatever). This wheel will turn and we will start to see personal and professional standards matter more as new generations of voters grow up without memories of the glib technocracy of Blair and with new memories of the mismanagement of Johnson and crew. When this does start to happen we need to attack these private think tanks and the role they play in our society.

You will never convince or win over the IFS but we may get a chance to reduce their role.

I have just listened to a deeply depressing and profoundly uninformative discussion of government borrowing on BBC Scotland news by the BBC Scotland economics editor, Douglas Fraser. Nobody here should listen to it. If you look for it on BBC Sounds, please – close your ears and hum.

Douglas has not got a clue…

That’s being kind

To channel Chomsky’s answer to Marr, someone with a clue would never get hired to do that job.

🙂