I attended a fascinating conference on alternative accounting at the University of Leicester yesterday. I was there to present sustainable cost accounting, but since I have shared most of the slides I used on this site before I will not do so again now. Instead I offer a couple of reflections.

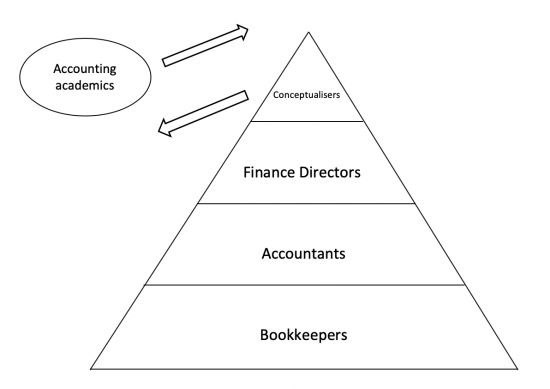

One is based on a discussion I had with an academic publisher during the lunch break. The discussion was on why there were no practitioners at the event, as far as I could tell. I outlined a chart that looked something like this that suggested an answer:

The pyramid is the accounting profession. Qualification might increase as one rises up the pyramid. What is also likely is that intellectual curiosity about accounting also does. But my point was that almost none in the bottom three tiers ask why they do what is asked of them. They data process, prepare accounts and ensure compliance with accounting and maybe other standards e.g. on tax, without really asking why they might be doing this. They deliver the product that the standard setters within the profession demand of them; reluctantly (usually) updating themselves as to the nature of these demands from time to time, but rarely questioning them as there is little incentive for them to do so.

In contrast, conceptualisers within the practicing profession, who think how to shape standards, are few in number. There are two reasons. The first is that there is very little time for many to undertake this activity. Second, outside the very largest firms there is even less reward for doing so.

Those that partake in this form of thinking - on just how accounts should be presented - are drawn almost entirely from the ranks of those large firms. And because there is pressure on them, like all partners in those firms, to earn a return their conceptualising is dedicated to matters that might earn that return by addressing issues that might suit the needs of their clients. And so we end up with, for example, the vast amount of effort that has been dedicated by the profession to accounting for derivative contracts when (let's be honest) there is no such thing as a derivative beyond its contractual form. It is an exercise in ‘make believe', supposedly designed for the purposes of mitigating risk but at least as often, I very strongly suspect, used to transfer value across borders with a very significant chance that tax saving results as a consequence.

The only other people engaged with this conceptualisation are academic accountants. Some of them are, in reality, as dependent on the big four and their client focus for their funding as any senior employee or partner of such firms, and so they tend to produce argument to support the structures those firms support. They are best described as facilitators rather than conceptualisers in my opinion.

And others, who are those I was certainly with yesterday, and are those who I have always been most likely to meet throughout my career, think almost wholly differently to those I call conceptualisers in firms. The questions that these academics ask - on the relevance of accounting, for whose benefit it is organised, how it might best communicate information, and to what end effect - frequently address issues that almost all in the profession thinks settled.

It has, for example, long been the settled opinion of accounting standards setters that all accounts, whoever might prepare them, for whatever reason and whatever their size or ownership structure, are prepared solely for the benefit of the suppliers of capital to reporting entities and then solely with regard to the decision that those suppliers of capital must make as to whether to engage with the reporting entity or not, as if this is a ‘take it or leave it' decision to be taken in a moment in a way only possible in a very limited range of financial markets in which almost none of those entities are engaged. No other possibility is considered. The matter is resolved.

I made the point yesterday that this assumption as to the use of accounting data is not fact: it is a gross and misleading assumption made to simplify accounting reporting within what might be called a neoliberal framework just as that same tradition assumes businesses only exist to maximise profit to simplify economic analysis within that same neoliberal framework.

In support of my comment I noted something called ‘The Corporate Report' issued by the Accounting Standards Steering Committee in 1975, and still available on the web site of the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales. Based on that work I argue, as they did, that there are at least six stakeholder groups for accounts:

1) Suppliers of capital

2) Trading partners, both suppliers and customers

3) Employees, past, present and future

4) Regulators

5) Tax authorities

6) Civil society in all its various forms.

In 1975 the profession thought the needs of all these groups should be met by accounting standards. It is fair to say that it has never done so ever again.

To conclude my first observation then: the arrows in my diagram suggest that these two groups fail to address each other because what each considers important is unimportant to the other. Firms want to reinforce the framework they work within, in which they have considerable intellectual capital invested, the value of which may be challenged by alternatives. The alternative thinking academics raise questions that the conceptualisers in firms will suggest are not even about accounting at all. They have sought to define what is normal: the ‘alternative' accountants do, as Prof Ian Thomson pointed out yesterday, make the mistake of conceding that right to define to them when in fact it is current professional thinking that is abnormal by seeking to address only a tiny part of the audience for accounting data whilst ignoring many of the issues of real concern, such as climate change.

And, secondly, this matters. Firstly, that is because most accounting undergraduate courses are constrained by the need to supply exemption from the profession's exams. This means they deliver a very narrow curriculum that has little relevance to wider society and instead reinforces the view that accounting has this narrow scope. So as my friend Prof Atul Shah eloquently argues, the curriculum offered is far too narrow to permit a real understanding of what accounting, accounting based decision making and professional ethics in far too many cases. The consequence is that we get accountants who simply accept the status quo, unthinkingly, because they are told this is 'normal' when it may not be so.

Second, we get frustrated accounting academics, I suspect, and that is not good for the profession or academia.

The answer is obvious: accountancy needs to open its mind, a great deal more than it is at present. The world faces the most enormous challenges created by a so-called 'normal' economy that is very clearly abnormal, and failing. Unless accounting manages to do this we are in trouble. And it has to do it very quickly. Whether it can is one of those great questions for our times.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

[…] Read here […]

I would suggest that accounts are still currently limited in providing details about the financial performance over a period of time or the financial health at a specific point of time. For the large organisations, terms such as Turnover, Cost of Sales or Admin Expenses are too vague to understand what they do and the Notes do not tend to give detailed information.

A slight tangential question for you then, given the need of the six stakeholder groups to rely on the FS of an entity, what more should accounts be providing in respect of a) future forecast information (which is far more relevant for current stakeholder and investment decisions) and b) timelines to prevent them being filed 6 to 9 months after the accounting period end date (to prevent decisions being taken on data which is 15 to 18 months old)?

These are issues the Corporate Accountability Network will address – but has not yet

I suppose it’s reasonable that most of those in the profession simply concentrate on knowing what they need to know to get paid. It’s what most employees do. It’s how hierarchical organisations operate. The ones who ask ‘why’ don’t get-on. Well mostly they don’t because they are seen as ‘trouble makers’.

The people who need to be engaging in the sort of session you attended and asking the questions are in government (and not just the treasury) because as you point out the stakeholder groups with a vital interest in accounting performance includes everybody.

Sooner or later our political representatives are going to have to come to terms with the fact that, as with economic policy, we cannot simply outsource public purpose to the private sector and trust bankers and accountants (and other professions too) to do the job even-handedly for the public good without government regulation.

We have a very negative attitude to regulation, because it tends to be framed in the form of ‘Thou Shalt not…..’. It is generally referred to as ‘red tape’ and everybody knows what a dreadful thing red tape is for tying up hands, and to some extent that is so because regulation is so often negatively framed to target specific abuses. It tends to be like Microsoft patches and we end up with the proverbial mended bucket which is all patches and no bucket.

Well crafted regulation should be a rudder, not a brake. But a rudder is of little use in this case without a destination of fit public purpose.

It would be nice to think that this was the sort of problem Dominic Cummings’ “weirdos” were going to address, but I think it more likely that he has a very different agenda in mind.

Are you saying I’m a weirdo? 🙂

Are you saying I’m a weirdo?

If the cap fits, wear it. But no. That’s not what I was suggesting at all. 🙂

Shame!

I’m not saying I think you are ‘normal’. 🙂

” accounting for derivative contracts when (let’s be honest) there is no such thing as a derivative beyond its contractual form. It is an exercise in ‘make believe’”

So you believe gains or losses on derivative contracts are fictional? Do you really believe derivatives have no financial impact? or purpose? So are you saying a company exporting goods or importing inputs should not account for currency hedges? And is it not a good thing they can mitigate the uncertainty of exchange rate fluctuations both on their costs and profitability?

You are as well aware as I am, I suspect, as to the truth of what I said.

“You are as well aware as I am, I suspect, as to the truth of what I said”..well not really when you make silly comment as the aforementioned accounting for derivatives

The problem is all yours

My comment was accurate

I am always amused at being told I am silly

It inevitably means I am too uncomfortably close to the truth for some given what I said was factually accurate

In other words ‘I have limited understanding of derivatives’ but I’ll try and bluff and hope I get away with it!

My description was entirely accurate

I knew exactly what I was saying

Sam,

Please don’t pretend that these speculative gambling instruments are there to assist the real economy.

That might have been there original purpose once upon a time but now the vast bulk of deriviative trades bear no relation to the actual production of goods or services. They are an end unto themselves.

Precisely

Exactly so, Marco. It beats working for a living and apparently is lots of fun. Especially when you get paid to play all day and when you lose somebody else picks up the tab. What’s not to like? 🙁

Spoken like someone else who doesn’t have the faintest clue about how the vast majority of derivatives are used – seems to be a common problem wth this blog!

Actually, the common problem with this blog is trolling from those who come to offer abuse to those who provide informed commentary that exposes the nonsense that those who promote the status quo claim is the truth, but about which those trolls never seem able or willing to provide any evidence.

“Please don’t pretend that these speculative gambling instruments are there to assist the real economy”

Depends where..at an industrial corporate level you are wrong. FX futures contracts almost entirely are used to fix the terms of payment or receipt of foreign currency at a date in the future. This helps planning and provides some certainly as opposed to be left wide open to the volatility of FX markets. The oil industry takes it further where one minute oil can be $80 a barrel where it is economical to extract, and next could be $50 where extraction would be loss making. Forward contracts/futures allow producers to lock in the level where they can sell oil.

In financial services and especially portfolio management derivatives can be more complex though again they are often used in the mitigation of risk (interest rate swaps, put sales or call sales/ put purchasing against long positions already held). Ironically leverage and so heightened risk is often only sought by some individuals who “punt” markets.

Accounting for derivatives is complex and in truth can only really be discussed by those who have a thorough understanding of derivatives in the first place

It is indisputable that futures contracts can have a use

Now explain their volume in any way that suggests economic reality justifies their scale

And then suggest why the excess are anything other than a financial engineering fiction for which the motive cannot be hedging

Precisely.

Sam Walker says:

“So you believe gains or losses on derivative contracts are fictional? ”

Good question. Perhaps you should think about it seriously. If the gains and losses are balanced (and I believe they are) the result is zero sum. So they may be useful in terms of cash-flow in particular circumstances, which I don’t dismiss the importance of, but overall are they producing anything ? I think not.

It seems to be a game of high stakes passing the parcel. But in reverse. When we played this as children the person holding the parcel when the music stopped has won, but in the money market version the ‘winner’ is holding valueless pieces of paper and has therefore lost.

The ratings agencies act as a sort of outsourced due diligence, but if their ratings are mince (as they were in the run up to the GFC) nobody knows what they are actually trading. The game is a perverse form of trading INsecurities. It goes nowhere good. Casino is the best description for this sort of activity.

Have you ever played the rather childish card game ‘Cheat’ ? If you play with a pack-and-a-half (a random shuffled half) instead of the normal full deck the players don’t know how many of any cards there are. Suddenly ‘six aces’ is not a claim you can reliably challenge. There may be as many as eight in the hybrid deck, but those six cards laid may be none of them.

This is the game that goes on in the City every day and the public is expected to believe this is what drives our national economy ? I don’t buy it.

Andy – Why do you bother posting on topics that you are clearly entirely ignorant of?

Your understanding of ‘derivatives’, ‘the city and ‘rating agencies’ would appear to have been based on prejudice and guesswork rather the experience, expertise or reality.

Still, I guess it will find favour on here.

I do not usually post abusive comments

But let me be clear, I am not at all persuaded you have any understanding of derivatives

Please lay out your precise qualifications and experience in verifiable form and then answer the question I asked earlier on how the volume of derivatives at any point in time can be explained

Do that, or very politely, you are simply being absuive

Stephanie Plowman says:

“Andy — Why do you bother posting on topics that you are clearly entirely ignorant of?

Your understanding of ‘derivatives’, ‘the city and ‘rating agencies’ would appear to have been based on prejudice and guesswork rather the experience, expertise or reality.”

OK, so why did the entire financial system collapse in 2008 then?

I post on things I don’t understand so that smart arses can explain them to me. I know what I’ve learned from commentaries on the subject. And when the Governor of the bank of England who supervised the GFC can’t explain the mess satisfactorily I look for answers because I’m curious like that.

So go ahead, explain why you crashed the banking system and how you aren’t going to do it again. Because I have every expectation that you will.

Ahh.. so Richard you now accept the use and value of derivatives in the industrial world but you are unhappy the with scale of transactions..fair enough. You probably need to spend at least 18m observing at a combination of entities including multinational corporations, Sovereign banks, Investment banks, Asset management entities /hedge funds and Governments around the world to allow you to provide an informed view…can they cause problems, particularly when retailed to those who don’t understand the risk? Of course. Can they become too opaque to the point where there become almost “black swan” type risks..of course..but are we going to go back to the 1800s when they didn’t exist ? of course not!!..so the accounting industry has to move with the development of the market..and i say it again…

Accounting for derivatives is complex and in truth can only really be discussed by those who have a thorough understanding of derivatives in the first place..and really that requires a high degree of numeracy, certainly a maths or engineering degree from a good University as a prerequisite..

This is a non complex narrative of how the derivative market has grown..

http://opencommons.uconn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1348&context=srhonors_theses

Ah….so leave it all to use experts

Always the resort if the charlatan in my experience

And you have not demonstrated you have any experience at all, to compound matters

I do not suffer fools gladly. You are bin that camp

Being able to spell derivatives would demonstrate greater experience and understanding the you, Andy or Marco have demonstrated on here.

This is just another laughable thread where you can make up any old nonsense on a topic you demonstrably have limited understanding of, and then claims it is others that don’t understand things.

For the record, I have CFA, CiD and ACiD qualifications. And you?

I asked for verifiable proof

I can find no evidence of that

Please do not call again

My CV is readily available

“…..Being able to spell derivatives would demonstrate greater experience ……”

Oh dear. Non existant or weak case, so we home-in on typos, grammar or spelling. 🙂

Standard Facebook form. 🙁

@sam walker

You posted this. http://opencommons.uconn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgiarticle=1348&context=srhonors_theses

Damn right the derivatives market is complicated, and this piece very early-on tells you everything that’s wrong with it as an industry.

It’s a casino. Taxing it would be dead simple. Government should simply place a levy on every bet so as to be in a position to bail the system when it crashes. As presently constructed the whole shooting match is quite clearly off the rails and the participants should be in rehab being weaned off their gambling addiction.

On the whole it would be rather better for society if most of the players were doing something productive with their skills. Particularly so since many of the players have very useful skill sets which could be put to better use. What a scandalous waste of talent, education and imaginative intelligence.

Just out of interest, I searched “what is a derivative?” and had a little read around. Given that apparently nobody on here understands anything ;p

To take a quote from one of the pages, which seems a typical description:

“Typically, derivatives require a more advanced form of trading. They include speculating, hedging, and trading in commodities and currencies through futures contracts, options swaps, forward contracts, and swaps. When used correctly, they can supply benefits to the user. However, there are times that the derivatives can be destructive to individual traders as well as large financial institutions.”

This sounds very much like betting dressed up in fancy clothing to me. Especially “They include speculating, hedging”.

One thing I have been trying to get my head around, and wonder whether Stephanie or Sam would be kind enough to enlighten me, is whether trading in derivatives actually does anything for the underlying asset? And if so, how?

As I read it, the purchase of a derivative does not add value to the underlying asset. The derivative gains (initial) value FROM the underlying class, but there is no mention of this value passing back down the chain the other way. “A derivative differs from traditional investments in the sense that an asset is not being purchased. Instead, an investor is solely purchasing a contract with another investor or institution. There is no actual asset being exchanged during the transaction.”

To comment on one of Sam’s comments further up thread “Do you really believe derivatives have no financial impact? or purpose?”

I can easily believe they have financial impact. In fact my gut feeling would be that derivatives have much greater financial impact than they should.

The purpose? I don’t know, given that the idea of stabilising prices could easily be done by the parties exchanging the underlying assets themselves. *In a year, I’ll supply you with x amount of y for z*. That should do it, shouldn’t it?

Thanks

The summary accords with what I suggested

And the imnpact, for too often, is tax abuse

You expect me to post my qualification certificate on here?

Lest we forget, I’m pretty sure your actual qualifications have nothing to do with derivatives – you are a graduate in economics and accounting who boasts about not bothering with most of the lectures and who is constantly claiming that everything they learnt was wrong.

Further, when you graduated in 1979, I reckon the amount of derivatives you studied was non-existent.

What other qualifications for derivatives you have?

Wow

First you reveal yourself to be a Worstall troll, as I might have expected, because that is the only place that the misinformation about what I said about my degree has been posted

Second, you reveal that you think no one learns anything after graduation of professional qualification

And their you then claim to know anything about accounting

With the greatest of respect, I suspect your only qualification is in trolling