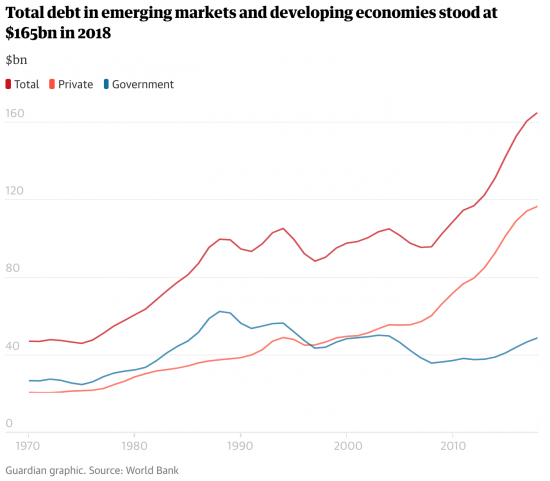

As Larry Elliott notes in the Guardian this morning, the World Bank is worried that debt is rising worldwide. This is their data:

Larry raises two concerns. One is the rise of personal debt. The other is that the data on national debt hides the fact that much of the growth is amongst developing countries.

Dealing with the latter first, the concern is very real. Debt is not a concern for a country like the UK, where we have our own central bank and currency and have issued almost all our national debt in sterling. We cannot go bust because by definition we can always pay our sterling debts. This, though, is not true of many developing countries where loans are often in a foreign currency, and usually the US dollar. There the whim of Donald Trump holds sway and could cause real problems, as would any downturn in world trade, which climate change might involve. There are real issues here.

But so too are there in the growth in personal debt. This is a symptom of over-consumption and incomes that are too low. I am not suggesting that the same people are doing both: they are separate but related issues created by an economy that promotes excessive consumption of goods produced at minimum cost to deliberately fuel debt, which then keeps people enslaved to the economic process that has ensnared them. This is the real crisis of modern capitalism, and the real reason why it is so frightened of climate change movements.

The solutions are threefold, and all are noted in my book The Courageous State.

One is to break the consumption cycle. The first way to do this is to tackle the pernicious role of advertising, which is always intended to make people unhappy.

Second, there is an obvious need to lift real incomes, the flattening in which has fuelled this crisis.

And third, there has to be a commitment to continuing low interest rates as anything else would fuel disaster and the most massive collapse.

But I stress, to argue that low rates caused this problem is wrong. It was the drive for growth, in GDP and debt, that fuelled this and brought the world to its knees in so many ways. And it is low wages for most that exacerbated that. Low interest rates are a symptom and not a cause. So let's tackle the real issues, and not the symptom.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

Whilst I agree real incomes should be raised there is a danger that by doing so debt increases because people feel better off and increase their borrowing and also of rising interest rates caused by growing economies. There would need to be a mechanism where some of the increase in earnings is funneled into debt repayment. How that would work I don’t know. The market would no doubt respond by encouraging people to borrow more due to the growth in incomes.

Is this “massive collapse” not a correction that is inevitable anyway? Is avoiding the correction nothing more than propping up a massive bubble market that rewards the rich at the expense of others?

If so, that leaves he question of how the crisis and recovery is managed, not whether the collapse can be prevented.

Most private debt isn’t personal or consumption related, most of it invested into asset price bubbles and a lot of it is corporate.

We can return to financial regulation and we can eliminate the tax-incentives to speculate, sure, but the era of regulation had higher interest rates than we have now. All eras did. No one wants double-digit official interest rates but near-zero rates are unprecedented and unnecessary.

Speculative excesses will continue to occur as long as people speculate with borrowed money and the return on their “investment” is much higher than the interest paid. The lower the interest rate the more they can afford to borrow.

Admittedly there is more to it than that but it is hard to separate high private debt levels from speculation and cheap money. The correlation between them is not just a coincidence. There is an inherent logic to it.

Irving Fisher understood that as did Minsky. Did they not?

I agree with some of that

But unless we include property speculation is not the big cause of debt – well over 80% of debt in developed countries is property related

Yes property speculation is the biggest cause of private debt both directly and indirectly. It affects the debt levels of normal home owners as well as speculators

But here’s the thing with that where interest rates are concerned – property is the speculative market that is most dependent on ultra-low interest rates. Property markets don’t have day trading. They operate on a time scale that involves months and years.

Most property speculators need to keep those mortgages going for years and pay for them out of their income before they can cash in to make their capital gains. Most could never afford the mortgages and interest repayments over time unless interest rates were very low – and THAT is the main link between low interest rates and massive private debt.

Is that what you meant about property? Because if it is it still leaves us with the prospect that very low rates are inherently problematic.

I don’t think it is true that ‘most private debt is invested in asset price bubbles or corporate’. For the UK personal debt is at a new record, I forget the exact figure but £1.2 trillion springs to mind. That is mostly personal loans, credit cards and mortgages. I think very little of that has anything to do with dodgy investments unless, as Richard says, you count houses as a bubble market (which they very much have been in the UK, but not often elsewhere – German house prices for example have not increased at all in 30 years net of inflation).

This is very much real debt and generally of the middle class or those at the bottom of the spectrum. The rich don’t need debt in order to afford what they want or invest.

So unless you want things to get very messy (revolutions, riots, etc) I would suggest that ‘pricking the bubble’ in order to get the ‘inevitable collapse’ over with would be a very bad idea. You would be talking about mass personal bankruptcy, homelessness, etc. On the other side major trouble for the banks, etc that lent it. Much better to get rid of the debt by higher wages and / or higher inflation.

You should bear in mind that historically real interest rates have been in the 2-3% range for a century or more. So 10% inflation + 3% real interest would mean a nominal rate of 13%.

I think you would find that the majority of folk with a debt would dearly love to get rid of it. So any windfalls are likely to go towards clearing the debt rather than racking up more consumption. I speak personally as somebody who has run up loads of debt to keep my small business afloat, buy plotters, etc and any spare cash I have goes in repayments. I was working out what I bought in the last 12 months and other than half a dozen items of clothing, a few things for the garden and one 2 week holiday it was nothing other than food and drink and utilities.

Timothy,

That is a quaint reply but is not really apt to suggest that “I don’t think it is true that ‘most private debt is invested in asset price bubbles or corporate’” These things are a matter of fact and record, not personal preference or opinion.

Yes, I do count houses (or residential property generally) as a bubble market, as do people in the housing and finance industry. For example:

https://propertyindustryeye.com/uk-housing-market-is-a-bubble-with-help-to-buy-pushing-up-prices-warns-bank-strategist/

It is a bubble market because house price growth is far greater than income growth, population growth (relative to supply) or growth in rents. House prices as such, are unrelated to to their earning fundamentals.

“The term bubble,” in the financial context, generally refers to a situation where the price for an asset exceeds its fundamental value by a large margin.”

https://www.investopedia.com/articles/stocks/10/5-steps-of-a-bubble.asp

House prices continue to be determined by the capital gains expectations of speculative landlords.

While capital gains expectations may determine the willingness to pay higher prices it is finance that provides home buyers (speculators and others) with the ability to pay those prices – to service the debt involved. And, to put it simply, those prices could never be afforded in the absence of very low interest rates.

The speculators know this as well. They expect that interest rates will continue to be very low into the future and that low rates will enable future buyers to pay even higher prices despite the more general stagnation in wage growth.

As for the matters of fact and record that I mentioned above. You lumped “personal loans, credit cards and mortgages” together as a category. That’s not customary. Statisticians tend to separate personal and property debt. According the ONS:

“Total household debt in Great Britain was £1.28 trillion in April 2016 to March 2018, of which £119 billion (9%) was financial debt and £1.16 trillion (91%) was property debt (mortgages and equity release).”

That’s on page 2 of this item and they have a graph for it on page 3:

https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/personalandhouseholdfinances/incomeandwealth/bulletins/householddebtingreatbritain/april2016tomarch2018#main-points

So that’s 91% of household debt sunk into the property market. The remaining 9% would also include a significant amount of borrowed money that’s dedicated to speculating on shares, derivatives etc.

I used the term “private debt” which includes corporate as well as household debt. It also the category that is identified in the chart that Richard has included at the top of his post (above). If we widen the scope that far we would find that nearly all private debt is invested into asset price bubbles and personal, consumption-related debt is miniscule by comparison.

https://www.theguardian.com/business/2019/jun/30/corporate-debt-could-be-the-next-subprime-crisis-warns-banking-body

Quaint or not ( and I am not sure the description appropriate) housing loans are real, do buy homes, and to burst the bubble will have the consequences Tim describes

That leaves a policy of low interest rates as absolutely essential and any control to be the subject of regulation

@marco

“House prices continue to be determined by the capital gains expectations of speculative landlords.”

And speculative home owners too…. the housing bubble (or at least irrational inflation of house prices) was initially driven by the home-owner culture promoted heavily by Thatcherism and obsessive ‘ladder climbing’ which made a great many people asset rich as long as they didn’t need anywhere to live ! ‘Everybody’ knew that was madness, but they joined in the Red Queen race, running to stand still. Speculative landlordism was a later-stage add-on, fuelled to my mind largely by distrust in the pension system, and enabled by the increasing inaccessibility of the first rung of the housing ladder for first time buyers. (Those two factors formed a baleful positive feedback loop).

What people would do about excess personal debt in the event of windfall income, or just steady rise in income is questionable. I spent a fair chunk of my windfall on debt reduction, but having learned from the banks and large corporations, I wouldn’t do that again. I’d just default, and or talk down the repayments. It works for bankers and they are the experts. It’s what they are ‘banking on’ now and they’re getting it, and are too big to fail still, so they’ll keep getting it.

Andy,

“Speculative landlordism” is and always has been the main game because capital gains are where the big money is. All that the owner-occupiers can do is borrow against the value of the asset (this includes those evil reverse mortages that a lot of retirees fall for). Some of them might also make a partial capital gain by downsizing or moving to a cheaper area.

Speculative landlords drive the prices higher because they can pay more and borrow more using their existing assets as collateral. “the home-owner culture promoted heavily by Thatcherism”, as you put it, got a lot of the regular home owners excited about going along for the ride.

Needless to say all this is done at the expense of prospective homeowners. Younger generations mostly.

OK Richard,

So Tim suggests: “that ‘pricking the bubble’ in order to get the ‘inevitable collapse’ over with would be a very bad idea. You would be talking about mass personal bankruptcy, homelessness, etc. On the other side major trouble for the banks, etc that lent it.”

And you apparently agree with him. The notion of it “being a very bad idea” infers that this would be an option or a choice. But an “inevitable collapse” isn’t an option – if it was it wouldn’t be inevitable.

Added to my previous point that avoiding the correction (is) nothing more than propping up a bubble market that transfers wealth from the young (and the poor) to the rich, there is also the fact that avoidance isn’t sustainable in the long term any way. Bubble markets deflate, corrections occur, with or without low interest rates This is not a case of if but when.

As for Tim’s suggestion that “its much better to get rid of the debt by higher wages and / or higher inflation.” I think that we both know that the debt is bigger than that solution would imply at any feasible level of wage growth or inflation, and presently, it is not just the debt but the wealth transfer that is problematic anyway.

Further to that point there is no avoiding the fact that affordability cannot be restored without present mortgagors experiencing some level of negative equity and unfortunately that includes innocent owner-occupiers. So what do we do – give up on affordabilty and generational justice because we can’t face the thought of a correction?

Here are two alternative thoughts:

In another recent post you proposed “removing tax relief from the assets that inflate to create bubbles” That’s an important idea and one that could do a hell of a lot to restore affordability slowly through attrition (by winding down incentives and expectations) rather than through the trauma of a crash. It wouldn’t guarantee a soft landing but it would help and it is the right thing to do anyway.

In the event of a crash investment banks should probably be allowed to fail. More importantly, savings banks should only be bailed-out (nationalised in effect) on terms that guarantee deposits and protect the mortgagors rather than the shareholders – on terms that protect the mortgagors from foreclosure, that is.

Both of those ideas require more detail of course but it may be safe to say that both are more pertinent than the idea of trying to perpetuate near-zero interest rates indefinitely and forever.

I stick with near zero interest rates – they are vital, as Keynes would have agreed

But regulation is a necessary condition

He would, of course, have included capital controls

We may do again

Yes Keynes had a thing about interest rates and rentiers. He knew that high rates were inappropriate when lending capital was abundant.

I’ve got nothing against low rates per se but inflation will (and should) occur eventually and, in the presence of very low rates, that brings about a negative real interest rate issue.

I can’t see how perpetual, near zero interest rates are compatible with a healthy, reasonable level of inflation.

I can live with negative real rates

I can’t wish a major financial crisis

We might get one

But I can‘t wish it

“….evil reverse mortgages that a lot of retirees fall for….”

Is that like equity release ? If so I don’t see what’s wrong with the idea if it were properly regulated. The entire basis of the home ownership fad was supposed to be a means of achieving security in old age. There’s not much security in having all your money tied in a property and having no income. That then morphed into wealth cascading down the generations from John Major. What a load of shite. A younger generation wishing its parents dead so they can cash in the house. What a recipe that is for social cohesion, and an expectation that society at large will pick up the tab for elderly care to protect their inheritance at public expense. The ground has shifted, probably because it was all just political spin in the first place. We have a national pathology about houses and homes. A house is a machine for living in or a store of capital or both. Equity release allows it to be both.

@Marco.

“I can’t see how perpetual, near zero interest rates are compatible with a healthy, reasonable level of inflation.”

I know there are advantages to borrowers in having inflation reduce the debt burden over time, but I don’t see why that has to be built into the system.

And I don’t see any inherent problem with low interest rates. Inflation and interest rates are a self perpetuating Red Queen contest. I can’t see why we need either. Fair interest should represent a compensation for opportunity cost. It’s silly to have it also compensating for inflation if you don’t need the inflation and could prevent it occurring. And why operate a system which debases the currency. At two percent inflation you halve the value of the currency every thirty-five(?) years. Why is that a good idea ?

What is this opportunity cost?

Saving has no macro function bar demand reduction

In micro terms the saver chooses it

What is the cost? Most especially when money is infinite, in macro terms, where overall rates should be set?

Marco, I think you entirely missed my point which is that most private debt has not been taken on with the primary intention being speculation. Since the graph is at a World level you should also be careful about assuming the UK housing market is in any way typical.

Looking at the same stats you did then mortgage debt increased by 3% while financial debt increased by 11% (and this is quite out of date as only up to 2018). Looking at the financial debt then nearly 30% of financial debt was student loans, and fairly similar for other personal loans. The rest is overdrafts, store cards, credit cards and HP. There is nothing in that which suggest to me any significant borrowing for speculative investment (e.g. in the stock market, bonds, etc). Also much of that will be quite high interest with personal loans anywhere from 5-10%, cards typically 18% and store cards and overdrafts often 30%.

So we are then looking at your property side of things. Buy to Let is certainly speculative, though I would say the median case is somebody with 1 BtL house that they are hoping will be their pension. There is the ‘top 1%’ and my business did some maps for one owner who had over 1000 houses in the South East. So that guy had a portfolio worth the best part of a billion given London prices, but that is far from typical. The majority of mortgages are normal home buyers. They might be hoping the value goes up but primarily they take out the mortgage as they need somewhere to live. Significantly raising rates and / or crashing the property market would cause a great deal of misery and personal trauma (evictions, bankruptcies, etc) and you could get serious disorder.

I think you are missing two things:

1) MMT teaches us that attempts by governments to cut state deficits, pay off state debt, run surpluses, etc will ipso facto simply transfer the debt onto the private sector instead. It is very clear in that graph as government debt was cut after 2008 private debt shot up instead. The English student debt is a blatant example of £35 billion of state debt that has simply been converted into private debt instead. The German government is running a €60 billion surplus this year and paying off Bunds, but as it is part of a currency union what it is actually doing is simply transferring German debt onto the other countries in the Eurozone (rather anti-social behaviour!). German behaviour is exactly the same as London within the UK. The much vaunted London surplus is simply the rest of the UKs deficit.

2) The UK property market has been deliberately manipulated by the state for decades. You had mortgage interest tax relief until the early 1990s, for example, plus a cessation of council house building and a variety of other policies designed to goose the private housing market. In my view this was to con the middle classes into thinking they were getting better off in order to hide the fact that real wages for most have shown zero increase since the mid 1970s. People were encouraged to support their lifestyle desires by re-mortgaging given their incomes were insufficient. This also supports the neo-liberal ‘trickle up’ policy by boosting demand for goods and services while also pushing the median household into debt (owed to the top 1% of course) and transferring real wealth upwards. All the money going into various help to buy schemes is mostly, of course, ending up in landowners and housebuilders pockets. It would have been much better spent building council houses.

I don’t think you can put all the blame onto UK citizens for going along with a housing bubble when the state has been using every carrot and stick available to whip them into line.

As I have said the UK property market is atypical. From personal experience with my late mum-in-laws house in Germany I can tell you it was bought for €150,000 in 1983 and sold for €289,000 in 2014. So almost doubled in 31 years. Not much sign of a bubble there. In fact after inflation then essentially exactly the same price.

So what should happen?

Firstly, a large increase in UK (and other country) state spending. But it matters very much what you buy. Spending it all on PFI charges, for example just exacerbates trickle up. So social housing, the GND, things with a high multiplier, education and training, basic infrastructure, etc. This should lead to higher real wages.

Secondly, some significant inflation to erase part of the debt. However, not facilitating asset prices such as houses rising at the same rate as monetary inflation. That would make house prices relatively cheaper (i.e. deflate the bubble) in a fairly painless way.

Timothy,

ONS stats on this subject from 2018 are not “quite out of date” because, on this particular issue, not much has significantly changed since then. More significantly, as annual stats go, they are the latest. 2019 stats that relate to that entire year are not available yet and unlikely to appear before the January 11th 2020.

As to The idea “that most private debt has not been taken on with the primary intention being speculation”

Clearly it has because that’s where most of the borrowed money has gone. If that wasn’t intentional then it makes for a very intriguing accident. Admittedly a lot of the property related debt is held by owner-occupiers – home-owners who are not speculators, and they probably outnumber the landlords and financial market speculators combined. So we could say that most of the property debtors are not speculators, sure, but that’s a proportion of the people involved, not a proportion of the money. Most of the borrowed money, the “private debt” is tied up in speculation.

Look again, for example, at the stats in the first 3 pages of that ONS paper. You’ll see that most of the most of the property related debt is held by richer people. And that’s despite the fact that there are proportionately fewer of them. That’s not mainly because they are paying off the expensive homes that they live in. It is mainly because they are the property speculators, the landlord class.

Anyway, the BIS based Steve Keen chart (Figure 10 in this article) reveals the relevant compostion of UK private debt:

https://neweconomics.opendemocracy.net/the-ten-graphs-which-show-how-britain-became-a-wholly-owned-subsiduary-of-the-city-of-london-and-what-we-can-do-about-it/

BTW The UK property market is not “atypical” as you suggest. For the purposes of this discussion it is comparable to housing markets throughout the English-speaking world and elsewhere, US included.

Regarding this suggestion: “The UK property market has been deliberately manipulated by the state for decades.” Yes, to create perverse incentives and encourage the use of debt (or drawing against equity) to substitute decent wage growth. Yes agreed. I wasn’t “missing” that. Many of us have known it for some time.

Now as to your suggestion about inflating away debt. Given the scale of the debt, that’s probably not realistic at politically tolerable levels of inflation. More significantly it is self-defeating if one’s aim is to keep interest rates very low (as this post suggests).

The experience of very low interest rates in recent times is usually accompanied by very low inflation. A significant rise in inflation will create a negative real interest rate issue that savers will hate and lenders are not going to tolerate. Banks will raise rates rather than lose money in real terms. Central banks will raise rates anyway if inflation is well above target.

Anyhow, it seems that you like MMT. In that case you’ll probably be familiar with Ann Pettifor. I’ll let her take over from here. I think that you’ll probably like this piece. I hope so:

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/jan/27/building-homes-britain-housing-crisis

“Secondly, some significant inflation to erase part of the debt. However, not facilitating asset prices such as houses rising at the same rate as monetary inflation. That would make house prices relatively cheaper (i.e. deflate the bubble) in a fairly painless way.”

That would require the work of a magician!!

Also lets not forget the pain of inflation and the problems it creates..

jason h,

He may not have expressed it clearly enough for your liking but Timothy was talking about the effect of inflation on real interest rates:

https://www.investopedia.com/articles/investing/082113/understanding-interest-rates-nominal-real-and-effective.asp

and the way that inflation erodes the real value of the debt.

This is not the stuff of magicians. Dynamo is far more more fascinating than real interest rates.