I spend a lot of time writing about the Global Financial Crisis. Not much of it is published yet: academia is desperately slow. The crash of 2008 and its aftermath is, however, an ever-present reality both in my work life, and to be candid, the world beyond it. But I still do not think we appreciate how much everything has changed. A blog from John Lewis who works for the Bank of England gave some hint of the scale of this change this week.

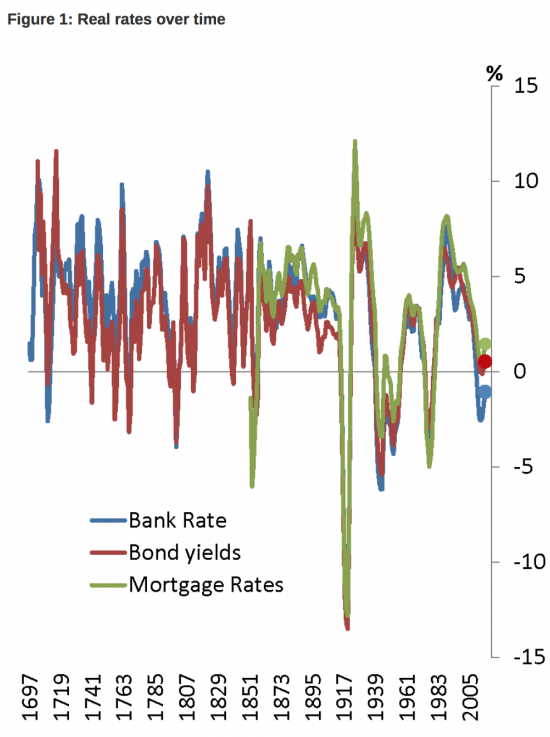

Lewis looked at real interest rates for three centuries i.e. those adjusted for inflation. When considering real bank rate, mortgage rates, and 10-year government bond yields over time this is what he found. As he notes: 'the lines show the five-year moving averages of the ex-post real interest rate. The dots show the values over the years 2012 to 2016':

As he notes:

The 5-year average of real bank rate rarely goes below zero — previous instances were mainly during the 1970s inflation and around world wars. The decline in real bond yields since the 1980s leaves them about 300bps below their all time average.

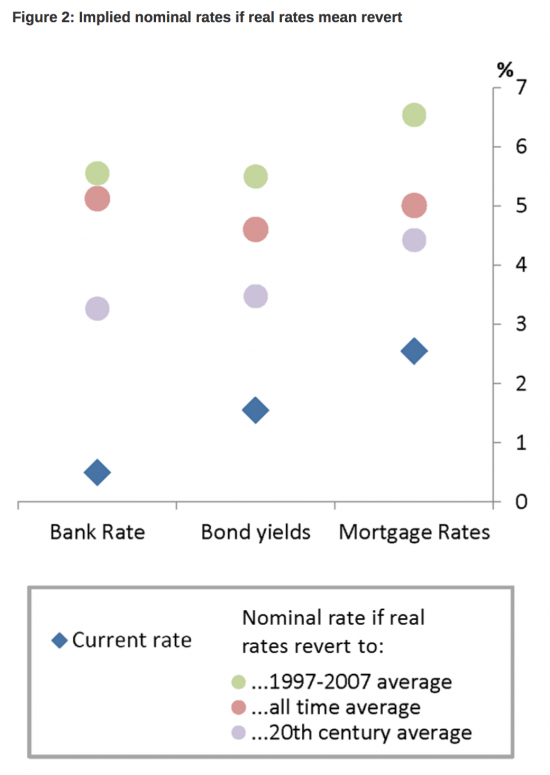

Now there may be good reason for that: broader markets, real reduced risk because of better information, and so on. The absence of world war helps too. But it also means that if we were to return to 'normal' or the mean then the change in rates would be massive:

The most useful contrast is with 1997 - 2007, of course. We're talking adjustments of four percent or more.

That is not going to happen. There are good reasons. Most mortgage holders would fail to make their payments. Most banks would then collapse. and government debt costs would increase and may politicians would panic at that whether appropriately or not. I will be blunt. Everything has changed. Those rates are history.

This though has massive implications. If this is the case then monetary policy as a mechanism for controlling inflation and economic activity has died: rates that let it work cannot be recreated. And yet almost the whole of macroeconomic thinking is premised on its use, as is the role of central banks in our economies.

The reality is that everything has changed. And yet there is, so far, almost no reaction. Fiscal policy - spend and tax - is the only tool left to the government now and yet no one is saying so.

No wonder I spend half my time wondering why we feel so out of control. We are.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

This may be a stupid question but it would help me to know the answer. You say everything has changed and I agree except for one thing. There has for a long time been the assumption that the bank rate can be used to control inflation. Does the current situation where it clearly doesn’t not suggest it never did ? Rather than that there has been a change?

It was always a blunt instrument, at best, like an ill-aimed cruise missile heading in roughly the right direction

What has changed is that it should never be fired now

We could draw a number of conclusions, including the surplus of Global capital ( from both increased pension savings in rich nations and huge sovereign wealth funds accumulated in China and major oil producing nations ) over the demand for attractive investment projects. We see a triple low affecting investment as consumer demand stalls because of income inequality, governments cut back because of neo-liberal objections to public spending, while the private sector is more interested in share buybacks to boost their own bonuses, than spending on reasearch and development to spur future growth.

This is particularly tragic as the World as a whole has huge needs for investment, and we are currently spending only around 1$T per year vs the $3-4T per year needed to achieve our Global Goals. The issue here is that Global investors still favour high-income countries, chasing a small pool of projects in G20 nations, instead of investing in higher risk developing countries where the best long term returns should lie.

Finally, the whole notion that national interest rate policies can control supply and demand factors that are now driven Globally is based on outdated economics. International supply chains mean that rising domestic demand in an overheating economy can now easily be met through imports without pushing up domestic inflation. This was exactly the situation in the runup to the 2008 crisis as G7 countries kept interest rates too low, ignoring the fact that it was only massive outsourcing to China that was keeping UK/US inflation under target.

Conversely, most inflation today is driven not by domestic demand, but by Global factors affecting input prices from oil and gas to growing international demand for food and specialist materials such as lithium for batteries. Recent inflation in the UK had nothing to do with the strength of the economy, but actually reflected the fall in the pound, affecting the cost of imports.

All this suggests that a model that expects national interest rate policies to control domestic inflation is as outdated as the idea that GDP captures what really matters about economic progress. Real answers can only come with new economic thinking that is based on more complex Global modelling. Of course these models will reveal the need for policy solutions based on formal international coordination – which is why we now desperately need a new framework for Global Economic Partnership. But thats another story.

Robert P Bruce – author http://www.TheGlobalRace.net

Can’t argue with that, Robert P Bruce.

We’re not holding our breath though, are we, until we see something done about it ?

The only golf club they won’t use? Big prizes await the political party that discovers that that one is the one they should use. Wake up McDonnel and Cornyn.

The parasitic classes have definitely reacted. Via Osborne’s QE, they’v awarded themselves billions and made themselves far more financially secure. (Dis)courtesy of the so-called ‘welfare reforms’, the poor are now much poorer, and more vulnerable to social disruption as a consequence. When the inevitable much larger financial crash comes along (in five, four, three…) the class which has caused it will be much better able to withstand its effects than any other classes. Reaction to the crisis of 2008 may not be immediately apparent, but it’s certainly there.

I’m not entirely sure if that’s true and it depends who you’re referring to. Some among those classes have borrowed to the hilt in order to buy the assets whose values will plummet in the “next crash”.

I am not sure if they are all more secure.

Marco Fante says:

Some among those classes have borrowed to the hilt in order to buy the assets whose values will plummet in the “next crash”.

One’s heart bleeds I’m afraid, Marco.

The real casualties are going to be the employees (and putative pensioners) who get stitched up by the corporates that have done this leveraging. Some estimates say 10% or European businesses are ‘zombie’ class and will crumble with ‘normalisation’ of interest rates. I guess UK companies are not far removed from that figure.

Trump’s trade wars are going to make ripples, and like rising sea level will swamp the low lying territories. Some of those low lying territories are not just little islands they are continental scale.

Interesting times, indeed.

“Fiscal policy – spend and tax – is the only tool left to the government now and yet no one is saying so.”

To be fair to him (not that I’m particularly inclined to be) Mark Carney did say in passing quite a while ago, (12 months or more I guess) that the Central Banks had done about all they could with monetary policy and that it was time for governments to get their fiscal arses in gear.

I don’t think he said it very loudly and I haven’t heard him repeat it, which is why I’m not particularly impressed with him. I often do wonder how he can possibly have been the best candidate for the job and why we needed to import him.

I don’t think Mark Carney is going to upset the oligarchy’s apple-cart by coming out and saying the way the UK monetary system works means there’s no need for an Austerity programme. Carney knows which side his bread is buttered on and there will be no Damascene Moment and an attack of morality!

Schofield says:

“I don’t think Mark Carney is going to upset the oligarchy’s apple-cart…”

Damn right he’s not. Useless sod.

WTF do they actually do in Threadneedle Street? They must be doing something surely?

“This though has massive implications. If this is the case then monetary policy as a mechanism for controlling inflation and economic activity has died”.

Yep, we know, you and us, we’ve said it all here before. And if monetarism (in the broader sense of the term being: the ascendency of monetary over fiscal policy) is dead then neo-liberalism is dead.

Because the rejection of fiscal mechanisms in favour of an “independent” central bank is at the core of the their theory. Its a central premise. I needn’t explain that. Its all there in the ‘New Classical’ and ‘New Consensus’ macroeconomics.

So, that’s why the current macroeconomic regime is a dead, zombie regime.There’s no point in anyone using platitudes to deny it. The Zero Lower Bound is a terminus, simple and plain. QE doesn’t assist the real economy. It inflates asset markets driving them further away from the real economy thereby hastening the next crash. The evidence of that is there in the relevant price-to-earnings (P/E ) ratios etc. etc..

This is the classic ‘Liquidity Trap’ (or a variation of such). Were all just in a holding pattern waiting for that stupid crash to happen.

I agree with all that

Marco,

“QE doesn’t assist the real economy. It inflates asset markets driving them further away from the real economy thereby hastening the next crash.”

Is that an inherent flaw of QE? I don’t think so. I think what we’ve seen is one particular and skewed application in the service of an elitist political ideology.

Green QE or people’s QE would be the same mechanism powering a different agenda with potential for diametrically opposite results or something moderating across the whole economy.

I think it important that we don’t ‘bad mouth’ QE as a mechanism because it’s been badly applied so far. We’ve seen just how powerful a mechanism it is by the way it has shored up the elements of the economy it was targetted at.

If those gains are to be maintained by the ‘elite’ who now hold them they are going to need some serious real economic activity to underpin them. The alternative is the expected crash of precarious asset prices and round we’ll go again.

The choice is to use QE (badly) again to repair the inevitable damage or use it productively to moderate and maybe even prevent the crash. I don’t think it would be too late, even now, to do that. Although obviously it would have been preferable to have started the process eight or ten years ago.

QE is money creation

Money can be created for all sorts of purposes

Like social media those purposes can be good or bad

Let’s appraise the purpose not money creation per se

100% right Marco. They ( being the politicians as substitute in the quote for businessmen ) are Keynes’s ‘ slaves to some defunct economist ‘ ; in this case the neoclassical nonsense that the macro is an expansion of the micro when it is nothing of the sort because ( and as you point out it has been rehearsed here many times ) it is not an expansion ; it is an entirely different category ( Aristotle is our man here ) . I am trying this out on my nearest and dearest of forty eight years at present and it is just beginning to go well having been subjected to ” Oh! here you go again on your money obsession ” for quite a long time ……..

This might be about to change with Trump spear-heading the Globalisation Without Compensation movement erupting in developed economies. As Jamie Galbraith argues the so called Great Moderation in inflation in developed economies has been heavily influenced by Chinese imports operating under a Chinese government regime of currency rigging and Functional Finance subsidies (state bank loan write-offs and roll-overs) to exporting industries which has enabled the capturing of price point in many developed economies.

https://www.marketwatch.com/story/economist-james-k-galbraith-isnt-celebrating-dow-25000-2018-01-08?mod=mw_share_twitter

Of course, many of these target economies also continue to target inflation through base or bank rate manipulation despite the slowness in taking effect (See UK Radcliffe Report). Trump’s campaign to make America Great Again by manufacturing more goods in the USA will result in wage and social security (state pensions) push to compensate for higher prices. The reduction in oil prices in the United States has been around in the country for several years now and been absorbed into the system. It is unlikely that inflationary pressures will come from this commodity especially given a big push to switch to electrically fuelled vehicles.

Schofield recommends:

We have a look at this, so I did. It’s not exactly radical firebrand stuff is it ? It reads like a prescription for sensible economic policies. Very much following in father’s footsteps. Why do politicians persist in ignoring wise counsel and doing the precise opposite ? I winced a couple of times thinking how our own government is proceeding.

https://www.marketwatch.com/story/economist-james-k-galbraith-isnt-celebrating-dow-25000-2018-01-08?mod=mw_share_twitter

And his father was brilliant

But so is Jamie

It’s clear from your writings that things have been out of control for a number of years.

Jane Parsons says:

“It’s clear from your writings that things have been out of control for a number of years.”

It could of course just be a deliberate policy of controlled chaos. Chaos creates opportunity for some and can be very lucrative until it gets out of hand. By which time the opportunists can have stashed their winnings.

[…] it has to be aware that, as I argued yesterday, the old economics is dead. All that went with it has to go including the supposed independent role […]

Let’s look at this another way: what would interest rates be, if they were set by demand for debt vs a rational estimate of the risk of default?

I don’t for a moment believe that either of these two premises are true: but you have to start an analysis somewhere, and no part of this economy is free of distortions and irrationality.

Firstly, the real-world deviations from the ‘expected’ line on our chart would show outbreaks of mass lunacy and the effects of bailouts that reinforce the principle that risk is for the many but never for the privileged few…

…Who return to the market, time and time again, with an ever-increasing share of all the wealth, purchasing rents with money whose ‘risk’ rate component is zero or negative.

Likewise, turn it over in your mind, a picture of what the demand-driven cost of debt should be, when the dominant demand is for (say) propping up consumption; or investing in productive enterprises; or financing the purchase of weapons in a global spasm of value destruction; or in purchasing tokens that confer the power of exacting rents on a diminishing pool of productive enterprises and their workforce.

The confusing ‘noise’ and zigzags of your charts today become much easier to understand; likewise, it becomes easier to ask the awkward questions about who is distorting the ‘natural’ rate, and to what ends.

When I look at figure 1 the over riding view I get is one of significant volatility. And therefore I think there is a danger in assuming too much from picking a small period (1997-2007) in order to make a point about the significant difference in rates between now and that period. The average for that period is far too sensitive to the start and end points and the specific period chosen.

I also believe that we are more indebted now as a percentage of GDP and in our personal lives – we are carrying ever increasing levels of debt in relation to our income. If that is true wouldn’t that also mean that we are all more sensitive to interest rate changes than in the past? Couldn’t you argue that the impact of a 0.25% rate rise now is like a 1% rise in the 1970s? And if so then can’t monetary policy can still work (certainly as a constraining factor through rate increases) without needing to be at the levels we saw earlier in the 20th century?

Your comment is mighty contradictory

First there is no discernible issue

Then the scale of the issue has reduced (which it has since 1980 since when there has been an overall notable decline in rates)

The fact is that when at or near the zero bound – which is where rates remain – there is no discernible evidence that monetary policy works. Even Mark Carney agrees

Why not agree we need to move on?

We are in the realm of game theory and the law of unintended consequences that I liken to a blind folded man walking up a staircase without realizing that other people are building the next step as he rises.

After my three page paper pictorial display was submitted to HM Treasury in 1997-8 via a secondee I showed that the fear of inflation was misplaced due to the acid rain of Japanese manufacturing techniques, supply chain and more. Shortly after interest rates started falling for no apparent reason. However the fear of chancellors was on bond traders with a previous chancellor saying when he came back after death he wanted real power – as a bond trader!!! Blair and Brown neutered that with the compulsory purchase by pension funds of long bonds. That distorted market has been added to globally by QE and just like in the PLC world with the fad for many tiny holdings in an index tracker fund the political or cEo perpetrators have learned that they can ignore those crying wolf as they have lost their teeth. People’s QE and an increase in small local banks would make a more resilient economy insulated from the rest of the worlds turbulence to some extent. The logical outcome and game played on politicians advised by accountants and bankers favours both professions and like the debacle of RBSNatwest who also learned to shout or manipulate their supposed masters. Tackle the causes not the symptoms. The framework for political decisions, the rules on pension funds the addition of local ethical resilience with banks without SNAC style committees to remove the jobs of those selfish individuals.

Gavin Palmer says:

“…… real power — as a bond trader!!! Blair and Brown neutered that with the compulsory purchase by pension funds of long bonds.”

Does this compulsion still apply ? – forcing pension funds to buy, even negative yielding, bonds if that’s all that’s available on the market ?

Small correction with SNAC committees